Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, journalist Lucille Davie profiles South African heritage icon Flo Bird. The piece was originally published on the City of Joburg's website on 4 October 2002. Click here to read more of Davie's work.

“Don’t ask me dates,” says Flo Bird, amateur historian and fiery 1,56m (five foot) tall campaigner for preserving old Johannesburg.

Bird, 59, lives in the house she was born in, in Parktown, jam-packed with interesting items, hundreds of books and wonderful artworks. She is “descended from Johannesburg pioneers”, and finds it “very exciting” to live in the city. For 30 years she has been actively involved in researching the history of the city and promoting the preservation of its heritage.

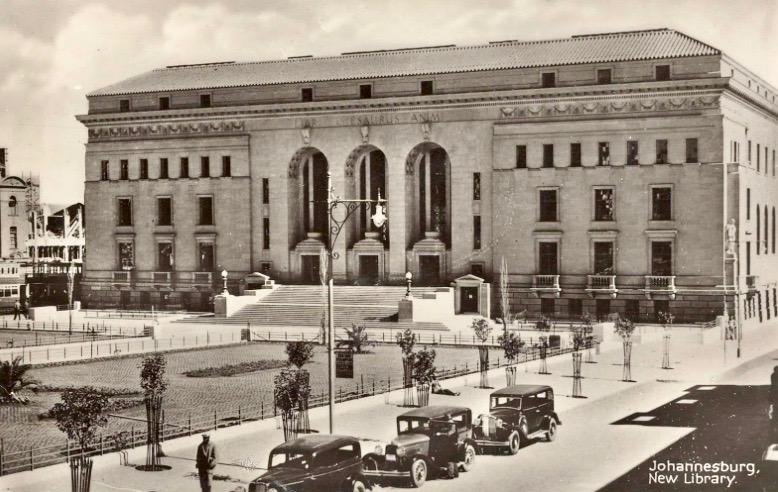

Her love of Johannesburg and its history came from visiting the central library with her father as a child, and wandering around the Africana Museum (now the Museum Africa) which was on the top floor of the library, in the city centre. “We used to pay our respects to David Livingstone’s door at the end of the gallery. We never looked at the silver, it was too boring.”

Johannesburg Public Library

Her leisure time is taken up with her full-time passion - the city - and like many Johannesburgers, she would never consider living anywhere else.

The city and its residents have got a lot to be grateful for having Bird as a passionate Joburger. In 1970 the city bosses proposed a freeway plan in which the city was to be crisscrossed by roads in the M6, which was to be six times the width of the present M1. It was to cut through many historic homes, like The View in Parktown, built in 1897, and its neighbour, Hazeldene Hall, built in 1902.

The View (The Heritage Portal)

Hazeldene Hall (The Heritage Portal)

The plan, called the Greater Johannesburg Transportation Scheme, was a proposal of 10 freeways, from M1 to M10, and was to be a noughts and crosses system of gigantic motorways, with the CBD in the middle box. It was to have a central island for public transport.

The battle to shelve the freeway continued throughout most of the 1970s and 80s.

It had more sinister implications, says Bird. The City Council froze development along the route, in an effort to drive down property prices so that they could buy the properties needed for the freeway, for next to nothing. Residents on the proposed route were frightened by possible expropriations, and didn’t consider alterations and renovations to their homes.

But the diminutive Bird and her colleagues won this battle, mostly through persistence, and living among middle-class homeowners.

”The new road was to go through old middle-class areas, and that was a mistake. For these homeowners their home is their biggest investment; it becomes part of their persona. Rich people take the case to court, but discover that that doesn’t always work,” says Bird.

Bird mobilised those middle-class homeowners. “We got people on to the streets, with banners, petitions, badges, and we threatened to sit in front of the bulldozers. Eventually the politicians became so damn scared.”

Sufficiently scared to back down - Bird sees this as one of her greatest triumphs in securing the heritage of the city and immediate suburbs. It also started her on her path of challenging the planning department of the city when they were hoping to slip through by-laws or approve plans, that she thought were not in the city’s best interests.

Now, years later, she is still very active and vociferous in pushing for retaining the heritage of old buildings and places around the city and suburbs, and for restricting property developers who chase money at the expense of preserving Johannesburg’s beautiful suburbs.

She was instrumental in forming the Parktown Residents’ Association, which, she proudly says, “has never been parochial - we have fought issues in Newtown, or the proposal for a waterfront development at Zoo Lake, or the loss of open public spaces in the inner city”.

Zoo Lake (The Heritage Portal)

She says they usually lost the inner city battles, “but we had the integrity to fight the issues”.

Although she is no longer on the Parktown Residents’ Association committee, developers still approach the Joint Plans Committee of the Association, with plans and proposals for the area, which includes Parktown, Westcliff and Parkview.

She qualified as a teacher but only taught for three years before taking up another job – raising her three sons. She’s a proud grandmother of three these days, but still enjoys researching any issues to do with preserving the heritage of Johannesburg. “The central library is still my favourite place.”

She has strong views on new buildings in Johannesburg. Take the Johannesburg General Hospital, opened in 1978, and dominating one of Johannesburg’s attractive ridges. Bird believes that the then National Party city council made a conscious effort to “smash the heart of British liberalism in the city”.

Charlotte Maxeke Hospital (The Heritage Portal)

”The hospital squats there over Harry Oppenheimer’s home, like PW Botha. It’s a horror and a disgrace,” she says, gesticulating with arms outstretched and a scowl on her face. It’s also difficult for ambulance drivers to get into the hospital quickly, she adds.

A further example of this Afrikaner imperialism in the city is the equally intrusive Johannesburg College of Education (now an extension of Wits University), for which several dozen Victorian homes had to be demolished. It was going to be Goudstad, the Afrikaans education college, which was eventually built in the suburb of Auckland Park. The dreaded M6 was to go through the St John’s school playing fields in Houghton. The school was designed by British architect Sir Herbert Baker.

Bird is the chairman of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust (now the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation), which she established in the mid-1980s. The Trust has an impressive library and offers weekly tours on a wide range of places of interest – from Nelson Mandela’s hideout in a flat in Hillbrow in the 1960s, and Herman Charles Bosman’s perspective on Johannesburg, to the early beginnings of the city.

”We created the tour programme to make things accessible, so that people could get to know about the city and its history,” she explains. The Trust has an extensive tour programme for school children, getting them thinking about history and its different sources.

Bird has mixed feelings about the new regime in the form of the new administration of the unicity. “The mayor and his office are too patient. They don’t like confrontation – they try hard to resolve problems through discussion which is great except when the other side fails to respond. This is foreign to us who have been fighting politicians for years.”

An issue that demonstrates this point is the tragic destruction of the historic Drill Hall in April this year [2002], when it burnt down, with the loss of five lives. It was in the Drill Hall that Nelson Mandela and 156 of his colleagues spent over a year during the Treason Trial of the late 1950s.

The building was owned by the national Department of Public Works, and was occupied at the time by hundreds of squatters, living in squalid, dangerous conditions. The City of Johannesburg is responsible for public health and they were concerned about the situation in the Hall and the possible outbreak of typhoid which would have spread further than just the Hall. They were in the process of taking the Public Works Department to court, after having tried other avenues.

The building was eventually given to the City, and barely a week later it burnt down.

Drill Hall (The Heritage Portal)

But, at least, says Bird, the City insists on public participation, which is “now taken for granted”, and guaranteed by the country’s new constitution.

”We have learnt to put in controls, especially with sub-divisions and rezoning, of property,” says Bird.

In fact, says Bird, city officials are now ahead of property developers, who now submit plans and proposals to residents’ associations first for approval.

When Parktown converted to office space in the late 1970s there was a proposal for four skyscrapers, including a 14-storey building next to the Sunnyside Hotel in Carse O’Gowrie Road, Parktown. “We opposed for three years and they held off the decision until the economic climate changed, so that by 1976 the developers weren’t interested in the cost of taller buildings. Now the tallest building is only 4-5 storeys high.” Bird concedes that they didn’t always get it right – “we are not town planners” – but they have certainly made officials aware of the issues.

I don’t mind if Bird doesn’t always remember the dates - she’s got many more important things on her mind.

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.