Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

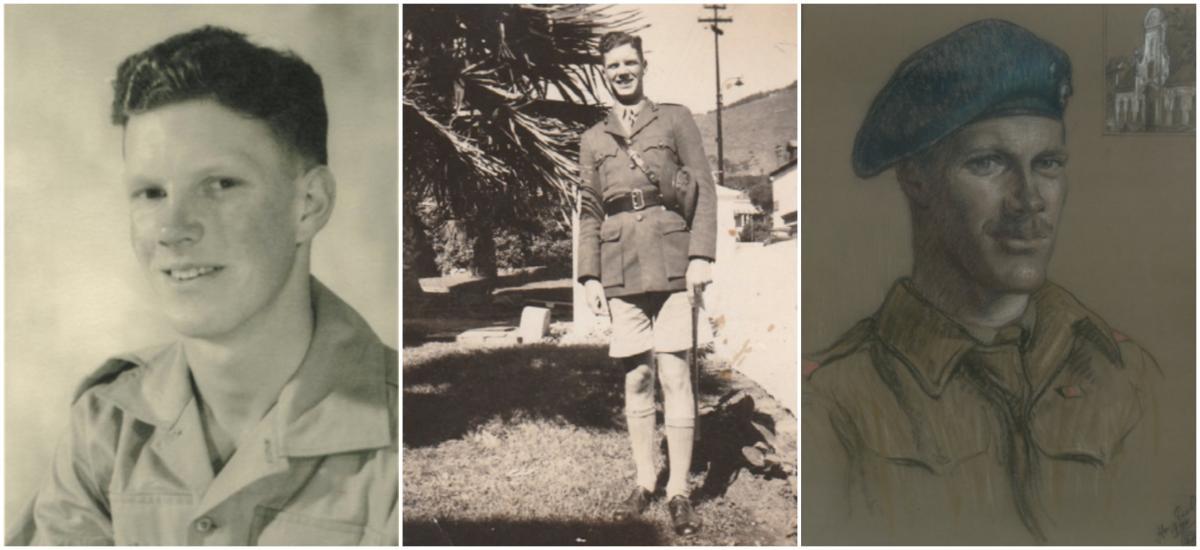

A Springbok is not only someone who played rugby for South Africa (or cricket in earlier days). The Springbok emblem is also a part of South Africa’s military heritage, albeit contentious. The 16th of February is the anniversary of the death of a Springbok, Lt. R.S. Bate. He died in the closing stages of World War II, during the liberation of the Netherlands, while he was attached to the 41 Royal Marine Commando. What sets his story apart from the deaths of other Springboks during World War II is that the portrait of this Springbok was one of three portraits of South Africans, who served during the war and represented their country and fellow Springboks; Bate representing the few who served in the Commandos. The portraits were exhibited in public only once, in November 1945, but the portrait is a heritage that has been a constant reminder to the nephews of the uncle they never met – and a reminder of cost of defending and pursuing liberty.

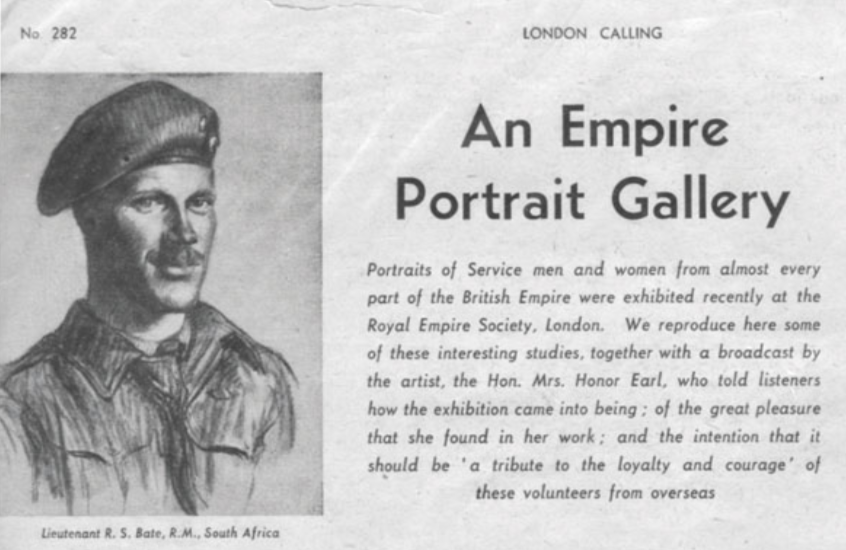

The Portrait by Honor Earle

A Springbok?

Few South Africans know that the antelope and the Springbok sobriquet applied to service men and women in the South African military forces, especially during the First and Second World Wars. The nickname was reflected in their cap badge which featured a Springbok (a ‘goat in a porthole’ to Diggers, the Australian servicemen). The motto at that time was “Union is Strength” and, initially, in the Dutch ‘Eendracht Maakt Macht’ and later in Afrikaans ‘Eendrag maak mag’. The Springbok badge was also engraved on some Springboks’ tombstones to indicate their country of origin.

A Springbok badge from World War I

Springbok badge engraved on the tombstone of Lieutenant R.S. Bate

Even fewer South Africans will recall the Springbok Legion or the Torch Commando that arose from it. These explicitly anti-fascist and anti-racist organisations were open to all Springbok servicemen, regardless of race or sex. They became a political force and some famous legionnaires later joined the African National Congress and its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, under the command of Nelson Mandela.

Every year, a two minute silence is observed on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month (Armistice Day) in many places of the world - in remembrance of the British and Commonwealth soldiers who died during World War I. Tens of thousands of young Springboks died during World WarI & II, but the Poppy Day practice and remembrance of fallen soldiers has virtually died out in their home country.

Both Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday, the second Sunday in November, are days to remember or reflect on those who died in World War I, World War II and later conflicts – and what their deaths mean. Both days are associated with the poppy emblem.

Veterans gather at the Cenotaph in Johannesburg on Remembrance Sunday (The Heritage Portal)

The Portrait

Honor Earle was a portrait artist in London, whose preferred medium was pastel. She painted a set of portraits of Allied soldiers in World War II. She was impressed by the young, lean, 6’1” (1.87m) South African and selected him to represent the Springbok Commandos. The inset at the top right of the portrait is of a building with typical Cape Dutch gables, which represents his having come from Cape Town, South Africa (he was born in Pretoria).

Lt. Bate’s portrait was one of four Springboks Ms. Earle selected. Col. Morton of Pretoria had been in the army in World War I; and three soldiers in her portraits served in World War II: Lt. Richard Bate, from Cape Town, a Royal Marine Commando; Midshipman H.C. Brown of the Eastern Transvaal and Lt. Parsons from Durban, who was in the S.A. Airforce. In November 1944, the Royal Empire Society hosted an exhibition of portraits of Allied servicemen during World War II as ‘a tribute to the loyalty and courage of these volunteers from overseas.’

An article about the exhibition appeared in London Calling

The Royal Empire Society was established as a ‘literary and scientific body’ dedicated to the greater understanding of what were then British colonies. It is now the Royal Commonwealth Society, a non-governmental organisation with a mission to promote the value of the Commonwealth of Nations and the values upon which it is based.

The 1945 newspaper clipping below explains how the portrait of this Springbok came to my grandmother.

Biographical sketch of the Springbok

Lt. Richard Shepperson Bate R.M. (26 May, 1922 – 16 February, 1945) was born in Pretoria, South Africa, to Maj. John Osborn Shepperson (Jack) Bate MBE (1880 – 1929), a South African, and Edith Jane Bate, née Harvey (1889 – 1974), who had emigrated from England to marry Jack. During the Second Anglo-Boer War, Jack Bate had served with the Western Province Mounted Rifles and general staff of the Cape Colony. He was awarded the Queen’s Medal with three clasps. In 1920, he was awarded the MBE (Civil) for services to the Defence Department. Richard’s father died tragically in 1929, when Richard was only seven years old. It was a difficult time for his mother, brother and sister. The family moved from Pretoria to Cape Town where Richard’s mother ran a B&B from their home in the suburb of Sea Point in order to supplement her modest military pension. Richard was a server at the Church of the Holy Redeemer, Kloof Road, Sea Point, where his name appears with others on a plaque in memory of those killed during the Second World War. He was a keen Scout and played rugby for Sea Point Boys High School. Richard had auburn hair and so his school mates soon called him Rooi-aas (the Afrikaans for Red Bait, used by local fishermen, a pun on Red Bate) – a bilingual play on words that did not amuse his English-born mother! After school, he joined the civil service: a stores surveyor in the Dept. of Roads at the Cape Provincial Administration, and played rugby in a team of the nearby Hamilton Rugby Club.

According to my father, Richard’s brother-in-law, Richard ‘became quite ill’ after matriculating in 1939. The family doctor diagnosed the problem. Richard was depressed: because he was under twenty-one years old, he could not ‘join up’ without parental consent. His mother just could not see her way to ‘sending him off to war’ but, after receiving the doctor’s diagnosis, she felt obliged to give her consent. The nineteen-year old joined the South African Army, initially, as a signaller with the S.A. Corps of Signals.

Signaller R.S. Bate, 1940

Richard was transformed and soon was on active service in East Africa; a gunner in the 2nd Anti-Aircraft Regiment. It seems, rugby was more dangerous than the enemy in Kenya. During a game of rugby in Nairobi, he was kicked on the ear in the region of a previous mastoidectomy (surgery performed when he was about five years old). After local treatment he returned to the Union and underwent Heavy Gunnery and Ant-Aircraft training. In April 1942 he received his commission and the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Six months later he was promoted to Temporary Lieutenant, his rank until he was killed in action. In November 1943 he left by ship for service with the 44th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the Middle East.

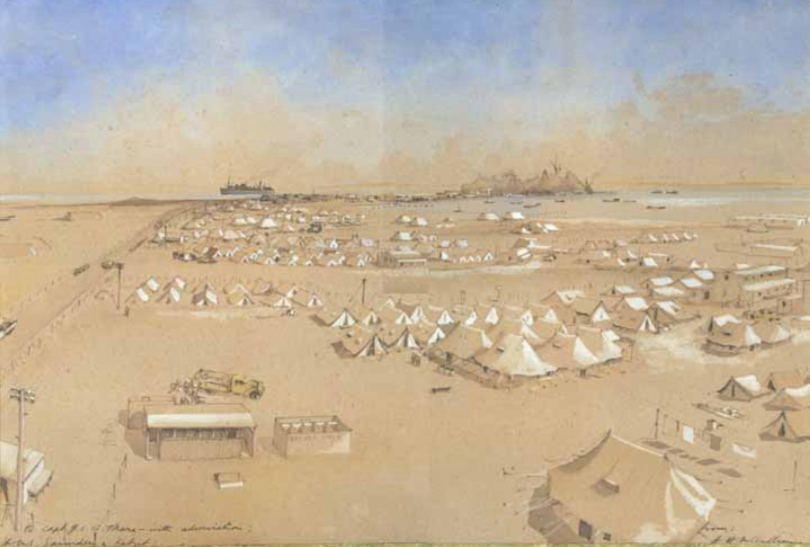

In 1942 the British Royal Marines were asked to form their own Commando unit. In February 1944, while serving in the Middle East, Lt. Bate volunteered to join the Commandos and was seconded to the U.K. forces. He was attached to the 41 Royal Marine Commando, the coastal raiding force and assault infantry. He remained in the Middle East because he was posted initially to HMS Saunders, the British Combined Training Centre on Egypt’s Little Bitter Lake. HMS Saunders was the first Combined Operations Training Establishment located outside the United Kingdom. Its purpose was to train Royal Navy personnel in the operation of landing craft and, together with the troops of many Allied nations, to practice amphibious landings prior to operations against the enemy in the Mediterranean and then in Western Europe.

HMS Saunders by Herbert Hastings McWilliams painted from the vantage point of the base’s water-tower.

Lt. Bate then was posted to the Portsmouth Division of the Royal Marines, which had barracks and headquarters in Eastney, near Portsmouth, now the site of the Royal Marines Museum. Soon thereafter he was appointed to the RM’s Support Craft Regiment; and, in October 1944, Lt. Bate was sent for Commando Training at The Royal Marine Training Group (Wales). The RMTG set up camps around the Mawddach Estuary to train Commandos in the art of beach assaults, while the Amphibious School at Tywyn trained soldiers responsible for maintaining the supply lines of such landings. In November 1944, he was appointed to the 4th Special Service (AKA Commando) Brigade and awaited operational deployment in the liberation of German occupied western Europe.

Lt. R.S. Bate, 1942, before he joined the Royal Marines; the R.M. flash insignia by Kbentekik (CC BY-SA 3.0); R.M. cap badge

Fatal Action

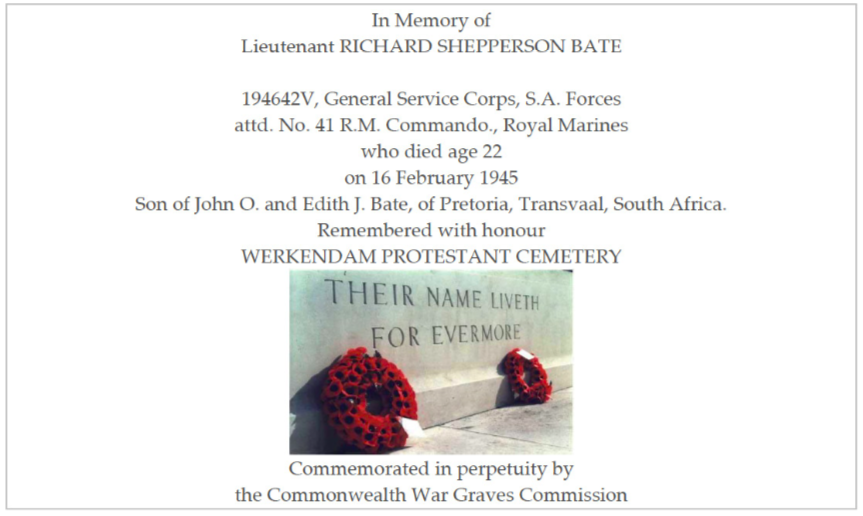

Deployment came within a month. His unit participated in the Battle of the Scheldt, together with Canadian Forces, during the liberation of the North Brabant region of the Netherlands. After the successful initial phases of the battle, only the Dutch island of Walcheren at the mouth of the River Scheldt remained in German hands. The Forty-One was involved in the amphibious assault on Walcheren, followed by action in various sectors of the Maas River Front: ‘December brought 229 more (casualties) and in the first 25 days of January, before the battle for Kapelsche Veer began, 164 of our young men died while defending a static front on the western flank of the Allied armies. Bate’s commando had been ordered to maintain forward positions on the small island of Kapelsche Veer, which lies between the River Maas and the River Oudermaas. The third unsuccessful attack by British and Norwegians was in the night of January 13, 1945. Bate was in B Troop that undertook operation HUSSAR on the 15th of February: after crossing to the north bank of the Maas River, B Troop was to capture prisoners for interrogation. ‘During unsuccessful action in the Waspik sector of the Maas River front, Lieutenant Richard Bate and Corporal Joseph McKenna were severely wounded during a river landing and had to be left behind when the patrol withdrew with other casualties’. Bate was reported ‘missing in action’ on the 15th. Two days later members of the 41 learned from a German prisoner that McKenna had died where he fell and that Bate was severely wounded and evacuated to a nearby (German) emergency hospital in Werkendam. The hospital was located at the converted Rehoboth Primary School, now demolished. Lt. Bate died on the 16 February 1945 while a prisoner of war.

Location of the emergency hospital at the Rehoboth Primary School (Corine Koek-Maasdam Werkendam Historical Society)

Werkendam remembers

The commandos Bate and McKenna were buried in the nearby Werkendam Protestant Cemetery: Lt. Bate in Row 7, Grave 5 and Cpl. McKenna, on his left, in Grave 6. There are twenty-four soldiers’ graves in the north-east corner: 23 British and Allied and one Polish; Bate is the only Springbok. He was but one of about 11 000 South Africans who died in World War II (of the 334 000 who volunteered) and one of 13 000 soldiers who died in the Battle of the Scheldt.

The citizens of Werkendam did not, and still do not, forget the contribution of Commonwealth and other soldiers to the liberation of the Netherlands. Local families have tended the graves at the cemetery since 1945. A member of the Van Oord family in Werkendam contacted Richard’s sister (my mother). In a poignant letter, Mieneke van Oord elaborated the Werkendam remembrance – and her special attention to Lt. Bate’s grave. ‘Since I was a young girl, I go, on the eve of the 4th of May, the evening on which we in Holland remember the victims and soldiers of World War II, to the little churchyard in the village where my parents live, in Werkendam ….’ Mieneke had visited South Africa in 1974 and, when she returned home in 1976, she noticed for the first time the Springbok emblem on a Werkendam gravestone (Lt. Bate’s). She continued: ‘Since 1976 I always bring flowers to this grave too. I sometimes make a flower arrangement in the colors of the South African flag.’ She still tends his grave.

One of Lt. Bate’s nephews, whose second name is Richard, was born the year after his late uncle’s death. He visited the cemetery sixty years after Richard died: ‘The graves are kept in beautiful condition and it is hard to realize that they are sixty years old already. Buried on either side of him are two men (fellow Royal Marines), E. Taylor and J. McKenna, who it appears were killed in the same action. There are several other similarly dated graves of men from Richard’s unit. The other graves are mostly airmen from a number of countries including Canada and Poland. Richard is the only South African, and there is a Springbok emblem on his headstone. There were gorgeous red tulips (it was late April) growing above Richard’s and E. Taylor’s graves.’

Lt. Bate’s grave in 1989, 2005 and 2018 tended by Werkendammers and British Legion

To this day, the soldiers who fell near Werkendam are remembered annually on the 4th and 5th of May, and their role in the liberation of the Netherlands acknowledged and appreciated. In addition to the annual remembrance in May, on Christmas eve the people of the Werkendam area light up the graves of the twenty-four liberators who died near the town. In November, members of the British Legion lay a wreath of poppies.

Werkendam lights at the graves of the soldiers buried in the Protestant Cemetery, Christmas Eve 2019 (4 May Committee, Werkendam)

A personalised, tiny wooden cross on Poppy Day 2018

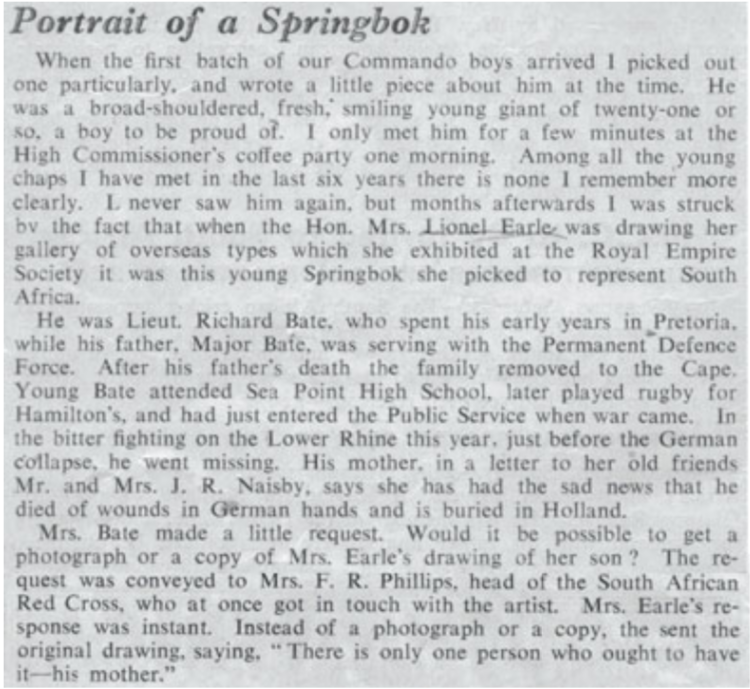

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has a commemorative record of Lt. Bate.

He did what was asked of him

The 41 Royal Marines were recognised for their gallantry. Winston Churchill was to write later about the Westkapelle operations at Walcheren:’ The extreme gallantry of the Royal Marines stands forth.’

Lt. Bate’s campaign and service medals: 1939-45 Star; Africa Star; France and Germany Star (includes the World War II campaign in the Netherlands – an uncommon medal); War Medal (British) and Africa Service Medal.

Lt. Bate was not awarded a medal for a specific act of gallantry, as was the case with many Springboks who paid with their lives. Perhaps the antiheroic title of a book on the Forty-One Royal Marine Commando says it all: “They did what was asked of them”.

I suggest that the annual commemorations at the Werkendam Protestant Cemetery mean much more than medals where the local citizens embrace the notion that ‘vrijheid niet iets vanzelfsprekend is’ … freedom is not a matter of course!

Acknowledgements: I thank Dewald Nel of Nel Militaria for assistance in making copies of Lt. Bate’s military records. I am grateful to Corine Koek-Maasdam, secretary of the Historical Society of Werkendam and De Werken (http://www.historiewerkendam.nl/) for providing information on the Werkendam commemorations, the location of the German emergency hospital and photographs. My family is also especially grateful to Mieneke van Oord for tending our Lt. Bate’s grave for more than thirty years.

About the author: Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals. Roger represents the International Map Collectors’ Society in South Africa, and is chairman of the Bibliophiles in Cape Town, and of the Friends of the Cape Medical Museum. Richard Bate was the uncle Roger never knew.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.