Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, journalist Lucille Davie unpacks the fascinating history of Sizwe (formerly Rietfontein) Hospital. The piece was first published on the City of Joburg's website on 4 November 2004. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

Back in 1947-48 the nurses and doctors of Sizwe (formerly Rietfontein) Hospital had no idea that the TB patient they were treating was a future Nobel Peace Prize Laureate. Archbishop Desmond Tutu recovered from the illness and went on to achieve great things - but he never forgot the hospital.

In 1995 Sizwe celebrated its 100th anniversary, and Tutu wrote a short letter for the centenary publication, praising the “gentle and compassionate caring from dedicated and skilled doctors and nurses”, ending with “Viva Rietfontein!”

Desmond Tutu (The Heritage Portal)

Sizwe still tends to the sick, treating primarily TB patients now, some of whom stay for up to two years, according to hospital CEO, Elizma van Staden. The reason, she says, is that because there’s a tendency for TB patients not to complete their six-month cure, their bodies develop multi-drug resistance, a much more serious problem, and one that can take more than a year to cure.

But the hospital was originally established to treat other diseases like smallpox and plague. Its last smallpox case was treated in 1965, the disease having been brought under control worldwide in the last decade or two. By then it was treating tropical diseases and in 1995 its name was changed to the Sizwe Tropical Disease Hospital, the only tropical disease hospital south of the Sahara. Diseases treated include malaria, typhoid and occasional cases of Congo fever.

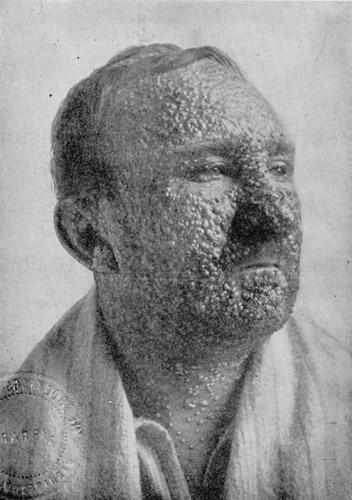

Smallpox victim in the early 20th century (Wikipedia)

The hospital works closely with Wits University, the South African Institute of Medical Research and the Department of Virology. It is also a teaching hospital, training nurses from the Free State and Swaziland in the treatment of TB.

One of the buildings at Rietfontein Hospital (Lucille Davie)

South African Institute of Medical Research Building (The Heritage Portal)

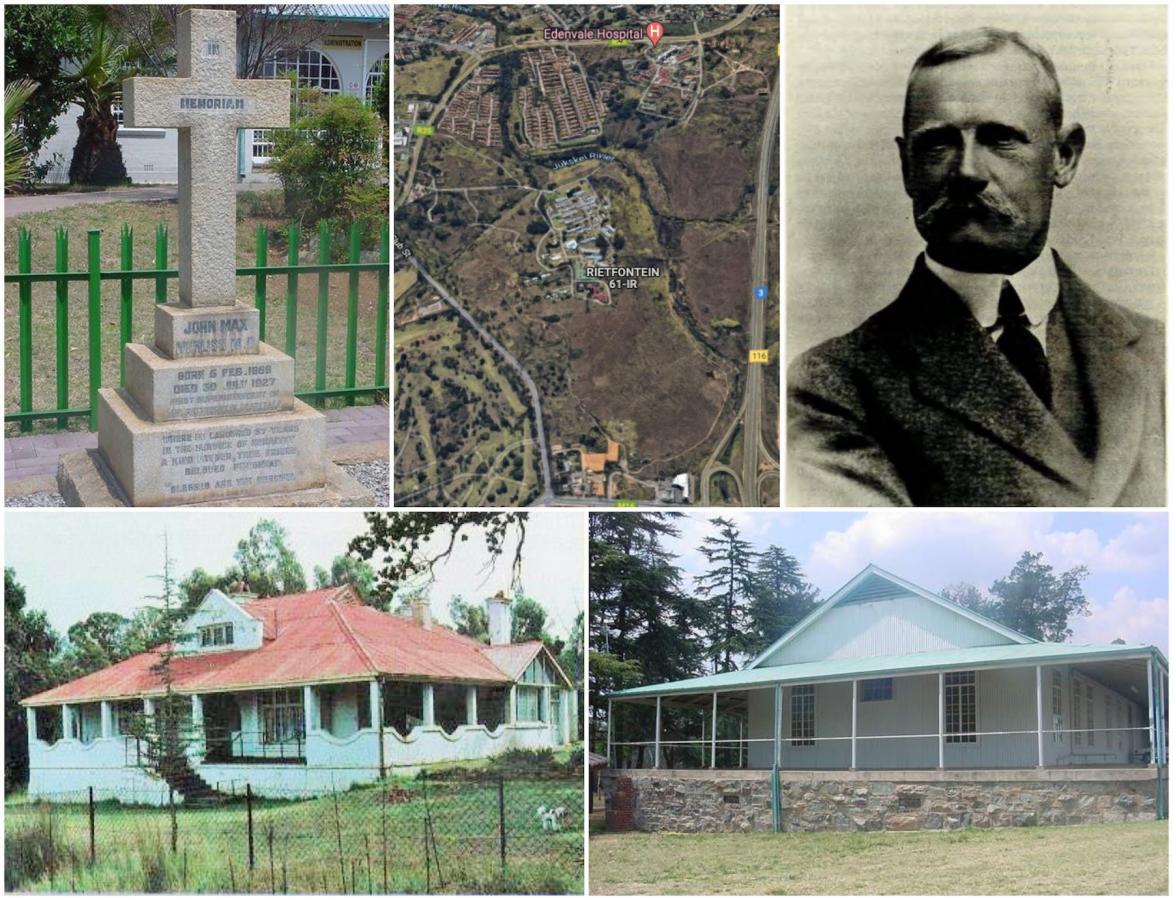

The hospital is also famous for another reason: its spread of a dozen blue and red iron-roofed, wrap-around veranda buildings is reminiscent of another era - turn of the 20th century Victorian Johannesburg – and ideal for period movie settings. Scenes from “Cry the Beloved Country” were shot here, and the hospital is still approached once a month for permission to film on its premises.

Some of the historical buildings at Rietfontein Hospital (Google Maps)

Smallpox

The first victim of smallpox was a Mr Hunter, a valet to an English aristocrat, who contracted the disease while staying at a hotel in the city. He was placed in a tent at Hospital Hill, just south the Old Fort in Hillbrow. More cases were discovered and one tent became several tents and wood and iron houses. A committee, the Kinderpokken Komite, and a sanitary board responsible for the camp, were established.

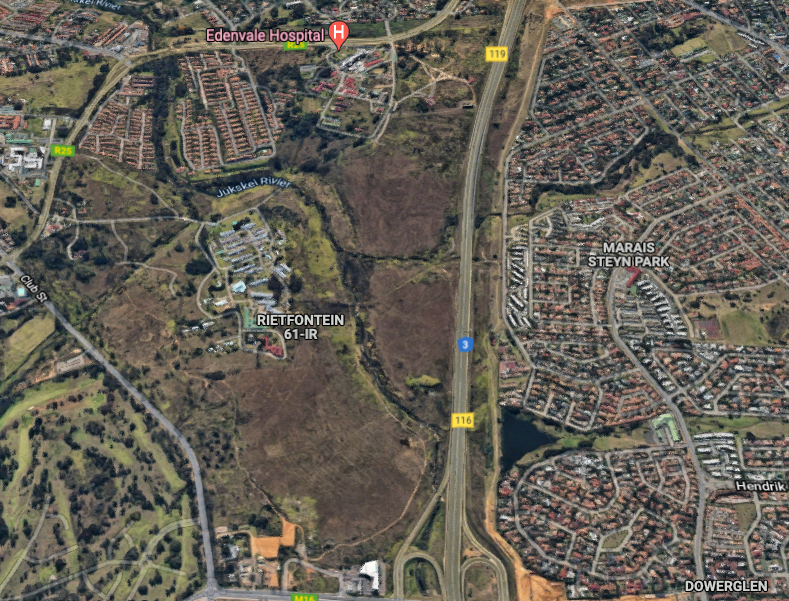

The disease spread and two other camps, at Geldenhuys Estate and Luipaardsvlei, were created. Some 2 200 patients were treated in 1893, but the growing town was unhappy with the close proximity of the patients, and so the Transvaal Republican Government bought the farm Rietfontein, of 750 morgen (around 700 hectares) in 1895 from a Mr Keiser. It was considered sufficiently far away from the centre of the town – a day’s march, on the far north-eastern border of the city’s precinct, around 30km from the CBD.

Only 320 hectares of the original farm remain, the N3 to the east having broken up the farm on that side, now containing the suburbs of Marais Steyn Park and Dowerglen. Modderfontein Road marks the western boundary, from where Sizwe Hospital is reached. Across the road is the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, the Department of Virology and the National Health Laboratory Services.

Location of Rietfontein Sizwe Hospital (Google Maps)

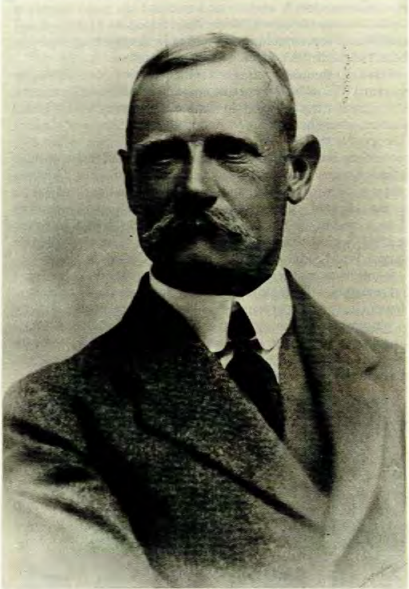

The first superintendent of the hospital, Dr John Max Mehliss, was considered one of the best authorities in the country on the treatment of smallpox and venereal diseases, which earned him an international reputation. Born in Grahamstown, he studied medicine in Germany, and after a spell in private practice was appointed district surgeon in Krugersdorp. He was appointed to Sizwe in 1895, where he stayed until his death in 1927, at the age of 59. He was known affectionately by his black patients as “Mielies”, as they couldn’t pronounce his name.

Dr Max Mehliss

His tombstone, originally in the hospital’s large unkempt cemetery, was moved, together with those of Matron Mary Middler and nurse Emily Blake (who contracted plague after kissing a child goodnight and died at the age of 27), to the front of the administration block. It’s believed that some 7 000 souls were buried in the cemetery, divided into black, white and Jewish sections, victims of smallpox, leprosy, plague and syphilis.

Mehliss Gravestone (Lucille Davie)

Graves at the front of the administration block (Lucille Davie)

Mehliss lived with his family in an attractive wood and iron house about a kilometre west of the hospital. Today it has been converted into a nurses’ training centre.

Older photo of the Superintendent's House

Mehliss gave lepers special treatment – in 1897 a leper asylum was built in the top northeast corner of the farm, consisting of wood and iron structures, surrounded by a 12-foot iron fence, and patrolled by armed guards. But in 1900 the patients were moved to Westfort Hospital in Pretoria, and 20 000 sheep captured by the British from the Boers were kept in the otherwise deserted building. At the termination of the Boer War in 1902 chronically sick patients were moved into the leper building, the first 18 men being admitted on 14 July, 1903.

Westfort Leprosy Hospital Building (Nicholas Clarke)

Once the smallpox epidemic subsided in 1898, with the vaccination of virtually the whole population of Johannesburg, the focus shifted to venereal diseases, and all prospective mineworkers, including Chinese immigrants, were examined.

In 1904 the plague broke out in Joburg and more than 1 000 patients were treated at Sizwe. Those who died were buried in a separate plague cemetery in the grounds, in graves demarcated by numbers only. The large graveyards are in a state of disrepair today, with gravestones toppled or removed and metal numbers scattered or stolen. Recently the invasive black wattle and blue gum trees have been removed. The leprosy and Jewish cemeteries have not been located - the burial register has been missing for years.

In 1909 space constraints led to Mehliss allowing veranda beds, and in that year total accommodation stood at 163 beds – 33 for women, 100 for men and 30 on the verandas.

Deteriorating conditions

Conditions continued to deteriorate at the hospital, however. Space demands did not abate, but a more serious issue came to the fore - the buildings were built of wood and iron, and paraffin lamps were used for lighting, posing a serious fire risk. One newspaper of the day stated that horses and mules at the veterinary school in Onderstepoort had electric lighting, but patients at Sizwe didn’t.

Three small fires had already been extinguished and a public outcry ensued. A public meeting was held in 1911 in which “the citizens of Johannesburg strongly condemn the conditions of the lazaretto [isolation hospital] and call upon the Government to take immediate steps to remedy the present state of affairs”.

The government finally relented and in 1914 electric lights and water-borne sewerage were installed.

Expansion

In 1923 a ward for “formidable epidemic diseases” was added, and 1936 a “pulmonary tuberculosis hospital” was also built. As the infectious diseases were brought under control, more TB patients were admitted.

In the 1930s portions of the farm were made available for the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation, now the National Institute of Virology, and a hostel and school for the juvenile delinquents, called Norman House. A retirement village, called Tarentaal, has also been built on the grounds.

In 1939 another outbreak of smallpox hit the city, and two more wards were built. But they were soon inadequate and tents were erected. Patients were dying at the rate of 20-30 a day and eight gravediggers were kept very busy. As a precaution against the disease lingering, quick lime was poured into the graves.

During this outbreak Prime Minister Jan Smuts innocently rode a bicycle through the hospital gate and past the yellow flag, collecting botanical specimens. He was detained by the gatekeeper and forcibly taken to be vaccinated.

Up until 1971 the hospital was able to supply its own diary products, but the dairy was eventually moved to solve the problem of flies.

From 1978

From 1978 onwards the hospital - the only one of its kind in Africa - has provided high-security isolation facilities for a range of highly infectious haemorrhagic viral diseases. The hospital has 260 beds and 290 staff, including 7 doctors, one social worker, one dietician, two radiologists and one physiotherapist. “It is a multi-disciplinary effort,” says Van Staden.

It operates on a R50-million a year budget, provided by the Gauteng province, which took over the hospital from the national government in 1986. Next year an anti-retroviral clinic will be opened. In December a new chief medical officer, Dr Kazombia Manda, comes on board.

Staff protection

Van Staden says special precautions are taken to protect staff. They are required to wear face masks and gloves in the wards and they are x-rayed every six months. An occupational health and safety unit monitors the health of the staff and there is also a staff wellness clinic. When patients are particularly bad they are isolated to prevent cross-infection.

And when staff need some time on their own they can wander in a portion of the 15 hectares of almost pristine grassland that surrounds the hospital. Because the hospital and its grounds have been fenced and isolated for over 100 years, the grassland has been largely left untouched, except for patches of dumped rubble, where builders have gained access to the grounds. Some 42 species of birds have been spotted in the grasslands.

At one time a society, the Friends of Rietfontein, was formed to protect the grasslands, but it has subsequently disbanded.

The tranquil Jukskei River meanders through the eastern edge of the grounds, with bright green Weeping Willows and eucalypus trees - supplanting indigenous trees and plants - dotted along its banks.

Lucille Davie has for many years written about South Africa's people and places, as well as the country's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.