Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

Geoffrey Klass was supervising the offloading of some old pieces outside his building when a young woman from a nearby business stopped to admire one, an Edison disc machine. ‘Ooh, that’s nice, what’s that?’ she asked. Klass told her it was a gramophone. ‘Oh, I’ve heard of those but I’ve never seen one.’ Klass smiled. She thought he was being friendly which he was, but he was also silently pondering how quickly familiar objects become forgotten; one generation’s marvel becomes obsolete in the next. Such is the speed of technological change stemming from the supercharged twentieth century that the Klass emporium of beauties, rarities and wonders, comprises, not only a collector’s paradise, but provides myriad cultural history lessons, in a vast uncatalogued museum.

Geoffrey Klass at work (The Heritage Portal)

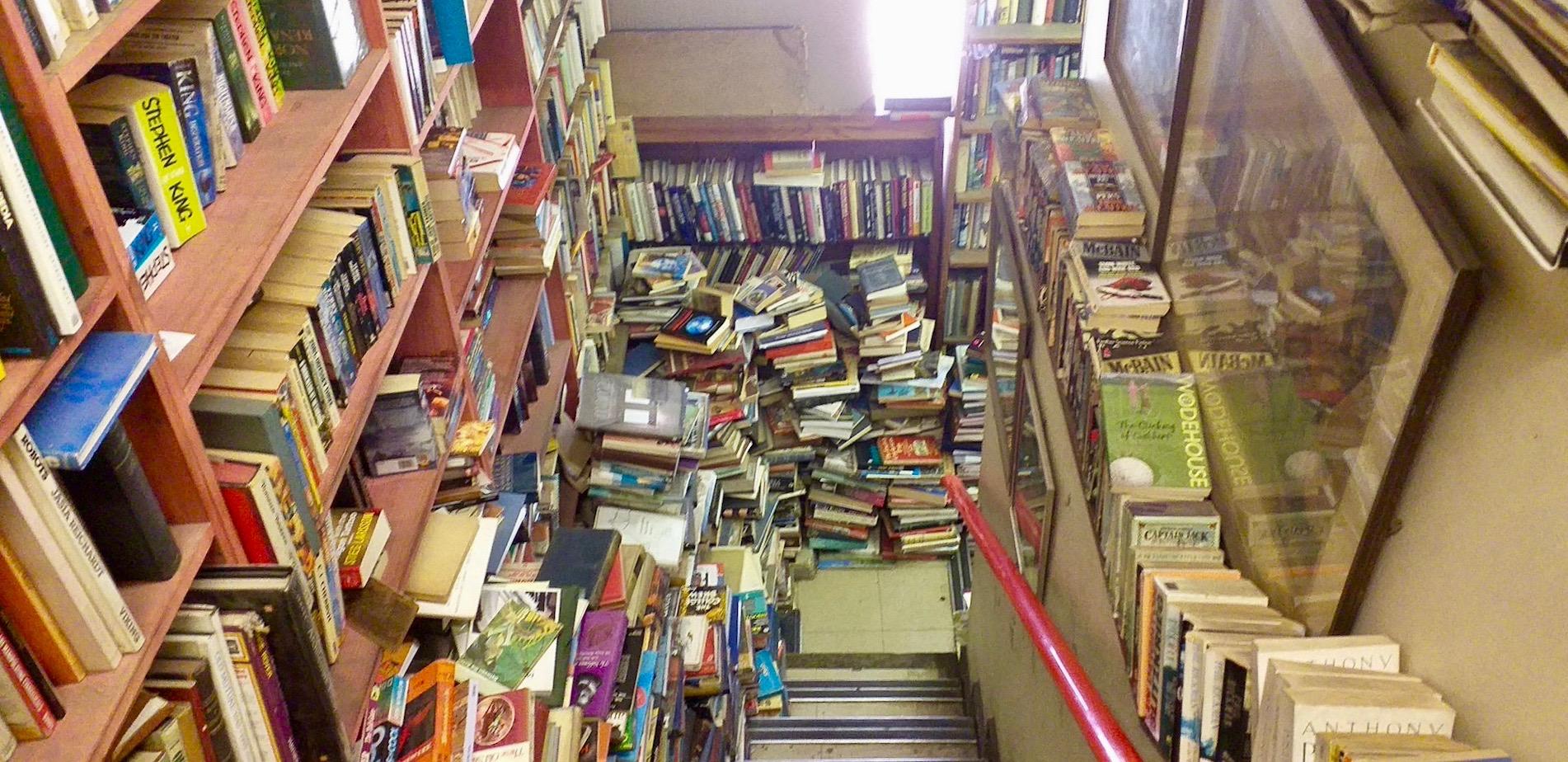

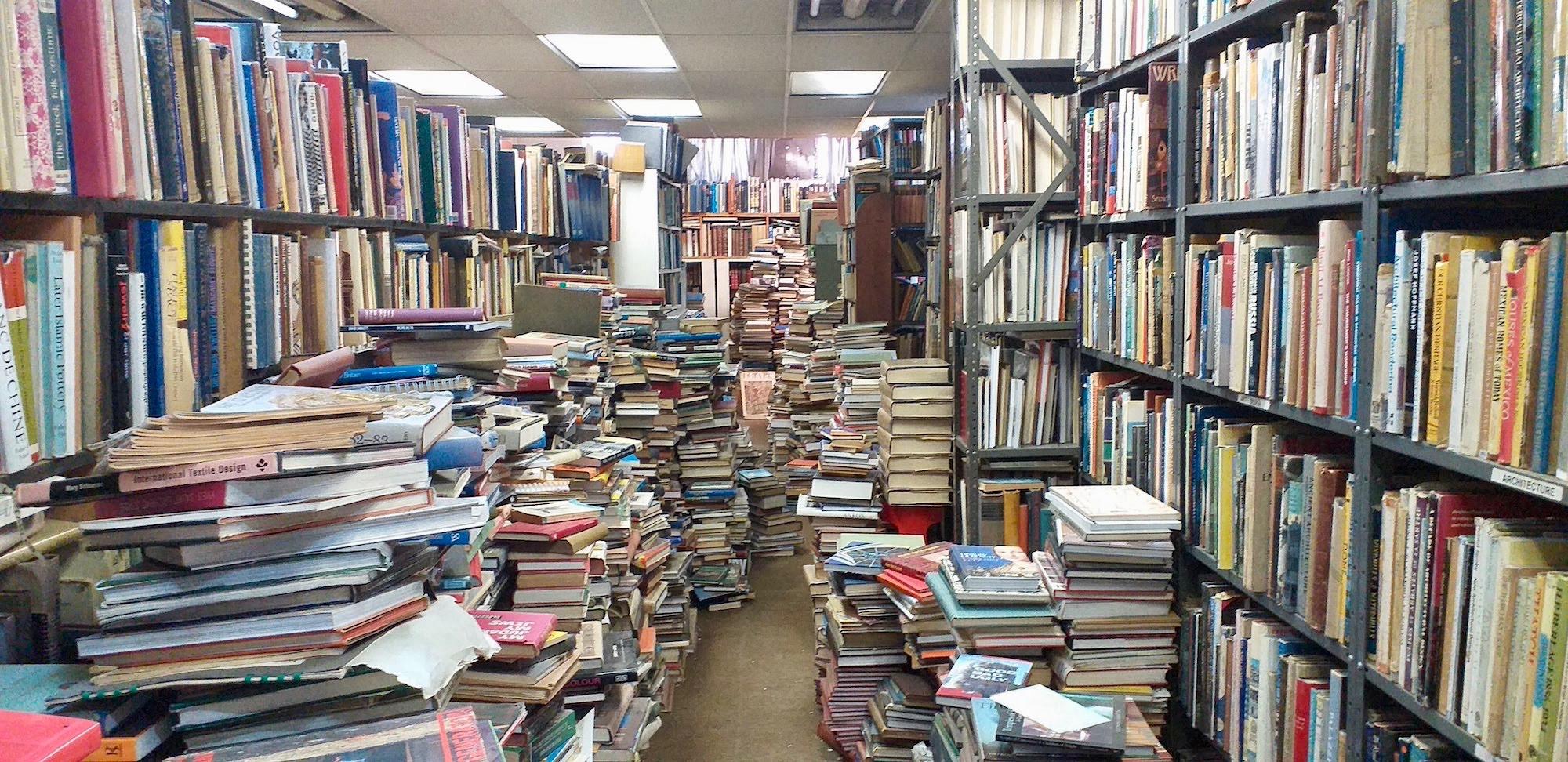

To enter Collector’s Treasury at 244 Commissioner St, deep in the old city, is to enter a world of munificent chaos: piled cartons of books clog the entranceway stairs and the narrow passage leading to the main display room. This contains a great profusion of rarities: glass, porcelain plates, vases and figurines, pictures and other desirable objects crowd walls, cabinets, shelves and floors. The Treasury occupies a 2000 square metre, seven storey building. Books, including rare Africana, swamp the basement shelves. One floor is almost entirely devoted to vinyl records. If they were all played at once you might conceivably hear the sound on the moon. Seekers could find almost anything at the Treasury, that is, if they were prepared to spend days in the search; but what a delight that would be. The Treasury is a comforting anchor resisting the overwhelming tides of contemporary culture. Overlooking their empire, the fifty something brothers, Geoffrey and Jonathan Klass, share a jumbled, dusty, sun filled office behind a glass partition where we met on a quiet Saturday afternoon to talk about their lives in the world of antiques and collectables.

Inside Collector's Treasury (The Heritage Portal)

The brothers at work (The Heritage Portal)

The brothers grew up in and still share the family home in that wonderfully otherworldly suburb, Parktown West. Apart from the heavens and the climate there’s very little of Africa in Parktown West. Unlike the rest of Joburg, the streets wander tantalisingly about, refusing to obey any grid pattern. The trees lining the streets and crowding the sloping gardens, hail from the northern hemisphere. Many of the houses could have been transported from genteel, middle class, Edwardian London. The architectural traditions of Herbert Baker are easily and often recognized. Not surprisingly, Geoffrey today sits on the suburb’s Resident’s Committee. Not much has dented its picturesque quaintness except perhaps the obsession with security. Geoffrey loathes the shared curse of Joburg, bunches of keys, fences, armed response companies, security gates, ‘always looking over your shoulder.’

Some of the houses in Parktown West (The Heritage Portal)

In this quaint suburban environment, the brothers matured in a home where, ‘From the time I could walk,’ says Geoffrey, ‘I remember being surrounded by objects in the house. Both my parents collected actively. My father was immersed in books. He passed that love on to us. My mother collected porcelain. Both were interested in art and antiques. They bought what they liked, what they wanted to live with. It was only natural that from a young age we started to accumulate objects. Not with commercial intent, but as with any collecting, you become aware of the commercial aspects of what you’re buying.’ Jonathan says, ‘Our peers didn’t have 100 000 books in their homes; they weren’t introduced to early opera singers. It’s that background that has produced Collector’s Treasury, that’s why we’re different.’ Why do they believe they’re different? Geoffrey continues, ‘We inherited a well rounded view of cultural matters and we were instilled with a love of objects and the history behind them. We don’t specialise, we don’t see boundaries, we see everything in a broad stream of culture.’ One quickly realises that there’s more than successful dealer to the brothers Klass. It would not be an exaggeration to label them cultural custodians. They enjoy possession as much, if not more than, commerce.

But, despite the family influence, neither brother showed any early inclination towards a dealing career. Jonathan, the younger, aired his singing voice and instrumental skills on air at the age of 17. He later performed with the famous folk singing group led by Keith Blundell. He took steps to combine his musical talent with the technology of recording and reproduction. As a schoolboy he owned and operated one of the country’s first portable video recording machines. But his career directions were constrained by the times in which he lived. He wanted to make documentary films but was unable to enter film school in London. For some time he ran a recording studio. The army hounded him. In the early seventies as a result of a politely worded rejection letter, he discovered that he was not politically correct enough to be employed in TV news by the Nat controlled SABC.

His decision to join the family business was not as easily taken as his brother’s. But, with other avenues seemingly closed, he became involved. Today, he does not regret his decision. It’s been pleasurable, it’s allowed him to indulge his passion for collecting, ‘which is a way of enquiring.’ And it seems, an all-absorbing way of life.

Geoffrey, had followed a more academic route, studying at Wits from whence he emerged with a B.Sc. and later, a B.Phil. in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. He was offered a Doctoral Fellowship in Chicago but then, in a major reassessment, he considered the vulnerability inherent in such an esoteric discipline. Perhaps an academic career wasn’t such a good idea?

Great Hall at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

At that point, ‘we sat down and discussed everything as a family unit,’ says Geoffrey, ‘and we, that is, my mother, Jonathan and I, decided to start an antique business from scratch.’ The initial stock came from the family collections. Today, they buy from deceased estates, from people on the move, from collectors, from auction houses and from other dealers. Their mother, a teacher who displayed ‘great business acumen,’ was a guiding light; she remained involved in the business until a week before her death in 1993. Dad, although retired, did not become actively involved.

Was it a wrench for Geoffrey to abandon academe? ‘It was painful, but my studies gave me an appreciation of the past, and techniques to investigate things,’ he says. ‘And it wasn’t as though the collecting world had not existed. If it became a choice between a lecture and a book auction, the auction usually won. I bought on auction for the first time at fourteen. My mother arrived to collect me from school to discover I was at an auction across the road from Parktown Boys where I bought a dinner service for four rand. I had a long history of buying. So it wasn’t a wrench, it was a gentle curve.’

Today with thirty business years behind him, Geoffrey is vastly knowledgable, his brain comprises a veritable collector’s encyclopaedia. He’s able to respond authoritatively to questions about most objects in the Treasury; an amazing performance. He admits however, to particular expertises in books and reproductive art; etchings, engravings, lithographs. Jonathan‘s special proficiencies embrace the fields of string musical instruments, toys, early reproduction technology. ’If someone asks, “How many strings did a banjo have in 1873?” I’ll tell them. Or, “who was the person who invented the fifth string on the five string banjo?” The answer comes automatically to me.’ Both brothers are known for giving advice unstintingly. Geoffrey says with a twinkle, ‘when people ask me, “What should I collect, how do I know if I’m buying the right thing?” I say, “Go out and buy the wrong thing.” It’s a field of hands on learning. That’s how you develop expertise. That’s how I learnt. I’m sorry that in this modern world, apprenticeship seems to be dead.’

Jonathan allows us into the mind of a collector: He says, ‘Of the two of us, I’m the major collector: a hundred gramophones, over four hundred musical instruments, electric trains.’ Jonathan’s wife and young son are avid collectors. His son is already talking about opening a bookshop. Jonathan continues ‘I can’t stop, I can’t help myself actually. I’m a collector of so many different things. I can’t even get round to cataloguing all the things I’ve got. For instance we bought four gramophones this week and a guitar and something else, so it never ends. It’s not for commercial value that I have these things. A gentleman from whom I bought a banjo came back the following week and asked to buy it back. I said, “Sorry, this is not for sale!” He got extremely upset. I said to him “once you’ve sold it to me, it has no commercial value anymore.”

Jonathan Klass (The Heritage Portal)

‘We bought the contents of a Balalaika band; the instruments, the sheet music. For me it’s history. Some people use old records as party invitations. It’s not something I would ever do. Every record has an historical content. Nothing is rubbish! In the twentieth century we were able to record so much. We’re in a fortunate position to retain stuff, but institutions like the SABC threw out all their tapes. So now we hold a unique archive of SABC recorded material.’

Jonathan’s indignation proceeds: ‘When they were discussing the millennium, searching for the man of the century, either Jimmy Hendrix or Madonna or some idiotic pop idol; did they think about Thomas Alva Edison? Without him we would have nothing, that’s why I’m a major Edison collector. People take things for granted. We get phone calls every day: “Aye have a collection of old records.” “Yes madam, what are they, seventy eights or LPs?” “Oh goodness, aye don’t know.” At one stage I used to say,” well you’re old enough to know,” but I’ve learned to be less undiplomatic now. I told one eighty four year old, “You were alive when those things came out.” She said, “They’re in sort of books.” I said, “You mean albums?” And she said, ‘they’re those thick ones with the hole in the middle.” People don’t have any impression of what they have.’

‘When I took a group of schoolchildren round the gramophone collection, they had no appreciation at all,’ says Jonathan. ‘They had no idea that there was a time when you couldn’t record sound or images. They take it for granted, without question. We, Geoffrey, my wife, my son, still wonder at things like, what made someone invent a gramophone or a printing press? We had the first expo of television at the Empire Exhibition in Milner Park Show Grounds in 1936. I asked someone the other day about the tower on the university’s west campus. He could see it, but he knew nothing about it. I told him, “it was built for the Empire Exhibition, it was called the Tower of Light and it became a famous feature of the Rand Show.” People can’t understand why I get so passionate about the Rand Show Grounds. Why should I care? Because I grew up with it. I remember the excitement of those show grounds, the pavilions, the restaurants, and that peculiar, daunting, strange atmosphere when it was empty, and now, no one cares any more, it’s all been obliterated with the help of Wits University.’ So Jonathan collects memories too; vanishing Joburg is precious.

Tower of Light (The Heritage Portal)

On October 1st, 1974, Collectors Treasury started in 300 sq metre premises in Stanley Ave, Milner Park. The brothers wondered whether they would ever stock the space? But they quickly outgrew Stanley Ave and in 1979, moved to a 500 sq metre floor in Pritchard House near the Supreme Court. In 1984 came a third move to Bethlehem House in Rissik St, where the business occupied ‘four small floors.’ The move to the present Commissioner St premises took place in 1991 and as already noted, it is yet again bursting at the seams, although several floors are devoted to the brothers’ private collections. Jonathan is building several layouts to display his collections of Lionel, Marklin and Hornby model trains.

Bethlehem House / Trades Hall (The Heritage Portal)

Geoffrey says it doesn’t matter that they couldn’t sell all their stock in several lifetimes. He goes on to point out that their capacity to spend money on day-to-day living is limited, ‘so as long as the business is providing for our basic needs, there’s no burning pressure to sell. Then you ask, “Why does one do this?” I think I know why. It’s not something you evolve as a stated purpose and then go out and do! But in retrospect, you realize you have been involved in hunt, kill and cart back. It’s part of a primitive throwback. Of course this is hunting without killing. It satisfies the need to pursue. It’s the quest, the thrill of going out and making a discovery, particularly when you come across something in the bottom of a bag someone’s left on the pavement to be carted away. Once you’ve brought it back you move on to the next hunt.’

Jonathan demurs, saying that as a collector, he enjoys the objects for their own sake. ‘Sometimes I’m sorry to sell an object we’ve found. I’ve so enjoyed having that object around that I’m sorry when it does go. Geoffrey echoes the sentiment, ‘I’m only happy to sell a book of which we have a duplicate in stock.’ ‘Now you know why we have so many,’ smiles Jonathan.

But there’s another important aspect to dealing. Geoffrey explains that in their business, there’s never a fixed supply of stock. ‘You cannot go out at will and find what you’re looking for so you have to think about the sorts of objects we should have in stock or should be replenished. It’s a form of investment, a sort of bet taking, it’s dealing in futures. It’s my Lotto; I bet this is going to hold its value, that’s going to increase in value. It’s better than money lying around in the bank. I’m betting that someone’s going to actually want this thing. Even if we’ve never seen one before, never sold one, we buy them, too.’ A tea bowl, bought at a well respected auction house for four hundred Rand was later identified by Geoffrey as coming from a century and country not specified in the catalogue, and which they later sold for seven thousand Rand. The brothers once found a set of Gustav Klimt original drawings. Despite the great profit, Jonathan regrets selling them, ‘if I found them today, I’d keep them.’ Jonathan continues, ‘it’s amazing what does become valuable; particularly books, like in earlier years, first edition Ian Flemings and later, Wilbur Smiths for example. We paid our whole year’s Internet expenses with Wilbur Smiths.’

Another shot inside Collector's Treasury (The Heritage Portal)

In describing the overall supply source for their business, Geoffrey notes, ’Johannesburg is still basically a mining camp. People aren’t settled. That’s why many people don’t like living here. It’s still a nine-to-five flurry to make money, coupled to a throw away society. People don’t buy things to hold for long periods, or build buildings to stand; it’s a put up, use, tear down, go on to the next, sort of society. Johannesburg has always been attractive for the pursuit of the fast buck. And people who have made good here, they’ve imported objects to give them the sort of comfort and status they would have had if they were living somewhere else. These are the things we dealt in during the fat years, but the supply of which is dwindling.’

Jonathan says, ’It upsets me that the following generation has no idea about the historic or sociological importance of the objects they inherit; all they’re interested in is the money. Often when we buy stuff from people, they just don’t know the significance of what they’re selling. That’s been a common factor throughout all the years we’ve been dealing. People we’ve bought from, have not really cared about what they’re getting rid of, except in terms of money.

Geoffrey talks about buying from deceased estates, where inheritors are sometimes only too glad to rid themselves of a parent’s or a spouse’s alienating obsession. Tongue-in-cheek, he parodies, ‘My mother was mad, she had four hundred teapots; what can I do with four hundred teapots? I don’t even drink tea!’ Jonathan says, ‘they’re often not even amazed that someone could have gathered such a collection. It doesn’t mean a thing to them.’ Geoffrey says, ‘We meet people who hate collections because they were a partner’s resented attention focus. We find widows who can’t wait to get rid of their husband’s books.’ Grinning again, ‘We buried him yesterday, would you like to buy his books?’

Yes, okay, the Klass brothers are dealers, they’re smart, they drive a hard bargain, they make money, but does their work have any greater significance? ‘Let me give us a pat on the back,’ says a smiling Geoffrey. ‘We contribute toward the preservation of a lot of material. Not so much hard objects; people don’t throw vases or antique cabinets away, they’re substantial pieces, but they throw paper, documentation, the building bricks of history, away. The things we’ve rescued out of dustbins! The things we’ve missed, “you should have been here yesterday!” Quite amazing, we’ve rescued a bundle of Jan Smuts’ letters out of a dustbin. Once I went to buy books from someone in Melrose. There were twenty black bags on the pavement with papers sticking out of them. ‘Do you mind if I take a look?’ It turned out they were Rayne Kruger’s [author of Goodbye Dolly Gray] letters. His sister had thrown away all his correspondence chronicling what it was like to be a struggling writer in London. Now those are biographical building blocks. You try and find an original printing of the Freedom Charter. We had one years ago. Now you can’t find them. I’m still desperately trying to find an inscribed Albert Luthuli book. He must have inscribed at least one, but where is it? Does its owner have any idea?

Geoffrey recalls that probably the most romantic material they’ve handled was the letters, photographs and documents belonging to a Simonstown ship’s chandler who supplied material to the famous Alabama. Among them was a testimonial from the Commander of the Confederate vessel recommending the outfitter to any companion vessel which might call at the Cape. Another piece of history was saved when the brothers bought a set of photographic albums and scrap books which belonged to Willy Rosenstein. He was a Jewish fighter pilot who flew with ‘Red Baron’ von Richthoven’s Circus in the First World War. The collection was rendered poignant and ironic by Rosenstein’s glowing discharge testimonial signed by none other than later arch Nazi, Hermann Goering.

Collector’s Treasury does not sell things to museums or libraries because there, the brothers assert, they are removed from circulation thus choking the life blood of the business, or, as is increasingly the case these days, books and historical objects get stolen and disappear forever. Over the last half dozen years they have, via the internet, successfully entered the world of international dealing. Such commerce makes up for dwindling local turnover but objects disappear into the wide world forever, a paradox for the brothers, who love items for their history, for the silent tales they tell.

Be careful when you visit the Klass brothers’ treasure cave, you may become obsessed with a set of Africana publications, you may be stimulated to learn more about oriental paintings, you may go home with an old photograph album filled with such anonymous intrigue as to cause you to draft your first novel. There’s always a chance you might find the very object for which you’ve hunted these thirty years past. Collectors Treasury offers you intrigue and quietude in the relentless world of microchips, rock and other unspeakable music, celluloid violence without end and ridiculously overpowered automobiles.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.