Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The Battle of Spioenkop in January 1900 is often cited as a remarkable convergence of three future world leaders - Winston Churchill, Louis Botha, and Mahatma Gandhi. While Churchill's presence as a journalist and Botha's role in the battle are well-documented, a fascinating historical question remains: Was Gandhi actually present at Spioenkop itself? Thank you to Neil Cairns for posing the following question which inspired this article:

Please can you help me with a simple question which I can’t find the answer to? The reference to the three future world leaders Churchill, Botha and Gandhi’s presence in or around Spioenkop at the time of the battle abounds in many articles. Churchill and Botha are obviously easy to account for, but I have not found a reference that actually puts Gandhi himself there. Obviously his corps of stretcher bearers were there, but I haven’t found anything that puts Gandhi there at all. Do you know of any such source or is this merely an apocryphal “good story”?

In books, articles and even quiz questions, the story of Gandhi at Spioenkop continues to be repeated. The story even appears on the interpretation boards at the battle site. This specific question about Spioenkop, reminds us that it is important to challenge an existing view if it isn't supported by the evidence.

Gandhi as a stretcher bearer

So before getting to the answer we need to look at the medical services in Natal before and at the beginning of the war in the Natal theatre.

In the months before the outbreak of the war, plans were made to prepare the army medical services in Natal in anticipation of the outbreak of war. Lieut Col P Johnstone laid the foundations on which the wartime organisation could be built. There were only sufficient Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) staff available in Natal to staff the military hospital in Ladysmith and one at Pietermaritzburg.

Thus the Natal Volunteer Medical Corps (NVMC) was created in 1898 from all the volunteer units that existed in Natal at the time. This was directed by Maj J Hyslop, Principal Medical Officer (PMO). The medical officers of the NVMC provided medical support for the military units in Natal during the first phases of the war.

The British government was opposed to non-white troops from the Empire coming to South Africa to take part in the fighting. Indian troops came to provide support duties. The Indian Medical Service arrived in Natal in early October, bringing with them four complete field hospitals. Three of these were for British troops and one was for the Indians accompanying the medical service, who acted as transport drivers and in other capacities. They served as both field hospital and bearer companies. The officers were members of the RAMC and all other members were Indian.

At the outbreak of the war, British forces were concentrated in Dundee and Ladysmith. After the battle of Talana on 20 October 1899 and the British withdrawal to Ladysmith and the subsequent siege of the town, the only military hospital to function in the province was in Pietermaritzburg.

As more British troops arrived in Natal, they came with their medical units. There was a shortage of hospitals along the lines of communication and Lieut Col R Exham PMO, who was to organise these, was besieged in Ladysmith. His replacement was Col Thomas J Galloway PMO of the 2nd Division who set about organising hospitals between Pietermaritzburg and the British camps.

No 26, 24 and 18 Field hospitals arrived in Natal from India, in October 1899. No 26 was sent up to Gen Penn Symons's force in Dundee and the other two to Ladysmith.

The Natal Field Hospital and Bearer Company had very limited staff - 8 officers, 2 warrant officers and 97 NCOs and men of the RAMC. They were used to strengthen the Station hospital at Ladysmith.

However, the medical support in Natal was attributed to “The most highly trained and complete field units, those for which provision had been made long before in the peace establishments and also the training of the RAMC.” Natal also had short lines of communication, allowing the constant supply of stores to the frontlines and the rapid and efficient evacuation of wounded soldiers. This efficiency was supported by the volunteer bearer companies that carried wounded from the battlefields to field hospitals and hospital trains.

In Dundee, a hospital had been set up in The Swedish Lutheran Mission station with Maj F A B Daly RAMC in charge. Here they treated both British and Boer wounded. After the battle and during the Boer occupation of Dundee, local Indian businessmen, who had remained in the town to protect their and their employer's businesses, acted as stretcher bearers carrying dead and wounded off the Talana battlefield to the field dressing stations and then to the hospital at the Swedish Mission station. This hospital continued until December, when Maj Daly and his staff were arrested by the Boer veldkornet in Dundee, and sent, in an ambulance train, as prisoners of war to Pretoria. From Pretoria they were taken to the Mozambique border. Maj Daly was reported to the Romer commission for treating both Boer and British wounded. As no formal charge was made, the matter was dropped and he later became PMO of No 18 general hospital in Volksrust.

In Ladysmith, the entire garrison of about 13 000 men, local civilians and those civilians who had left Dundee with the British troops on 22 October were all caught up in the Siege. A total of almost 21 000 people were crammed into the town and epidemics of typhoid and other diseases led to a considerable number of deaths during the 3 months long siege. There were hospitals in the Town Hall, at Intombi camp and at the station. 10 673 admissions were recorded from the total garrison of 13 497. This did include repeat admissions, but the numbers are still extremely high. 5 of the 46 RAMC staff and 2 of the Indian Medical Service died during the siege and almost half of them suffered from typhoid or dysentery.

Around the town of Ladysmith, No 4 Stationary hospital was the first hospital on the lines of communication and handled thousands of wounded men. It had its own transport and against all the rules for stationary hospitals, it had nurses so close to the front lines. Explicit instructions were given that the nurses would be evacuated immediately should the need arise. This hospital, under the command of Mr Frederick Treves, was described as “a hospital liberally supplied with all the essentials of a general hospital on the lines of communication.”

The hospital dealt with large numbers of wounded from the Battle of Colenso (15 Dec 1899). In January 1899 it became a “temporary mobile hospital of 300 beds“ and moved with the army to Spearman’s farm, where it dealt with the casualties from Spioenkop and Vaalkrantz. As the army withdrew, the hospital moved back to Chieveley and here received 400 patients from Intombi hospital. The hospital was based in Newcastle from June to August 1900 and then moved to Standerton. In January 1901 it became No 17 General hospital and remained at Standerton until the end of the war.

The Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps was raised mainly from refugees from the Witwatersrand, who had fled at the first signs of war. They were constituted under Col T Galloway, principal Medical Officer of Natal and were paid 3 shillings per day. There were just over 1 000 people in the corps.

The Natal Volunteer Ambulance corps usually removed the wounded from the battlefield, while the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps men carried the wounded from outside the firing line to the base hospitals – sometimes great distances from the battlefields.

Most likely the Natal Indian Ambulance (With the Flag to Pretoria)

Initially the offer by Gandhi to raise an Indian Bearer Corps was turned by the Natal Government. However, as the war unfolded it became apparent that every bit of help would be needed. During the early stages of the war, the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps was recruited from among Indians in the Public Works Dept and from free and indentured labourers. This corps raised 300 free Indians and 800 indentured workers, representing a quarter of the Indian population in Natal and were trained by Dr Booth, who served as their medical officer.

This was the stretcher bearer corps that Mohandas K Gandhi was involved with. Although he personally believed that the Boer cause was just, he also believed that for Indians to achieve freedom and independence, as members of the British Empire, then this was an opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty and worthiness by supporting the British cause. He was given the title of Mahatma, just before he left South Africa in 1914, which means 'Great Soul'. Thus it is incorrect to use the title 'Mahatma' Gandhi during the Anglo Boer War.

The intention was that their services would be free of charge and all costs would be borne by the wealthier members of the Indian community. This is an error in interpreting historical events and repeated generation after generation. The salary lists of all these men are held in the records of the Public Works Dept in the Pietermaritzburg archives.

On 15 December 1899 the first Bearer company arrived at Chieveley and assisted with carrying wounded from the field hospital at the battle of Colenso, to Chieveley station – a distance of 6 miles. The corps was disbanded and all members were back in Durban by 20 December 1899. A second Bearer Corps was called up on 7 January 1900 and within a week had over 1 000 men at the front. They were finally disbanded on 14 February 1900, shortly after the relief of Ladysmith.

Their work was highly commended by Gen Buller and 34 members of the corps were awarded the Queen's South Africa war medal. Gandhi’s medal is on display in New Delhi, India. Although Gandhi put in a motivation for an issue of the Queen’s chocolate Christmas gift tin, this was turned down with the explanation that it was only given to enlisted men.

While records show Gandhi's valuable service with the stretcher bearers during the South African War, his exact location during the battle of Spioenkop deserves closer examination.

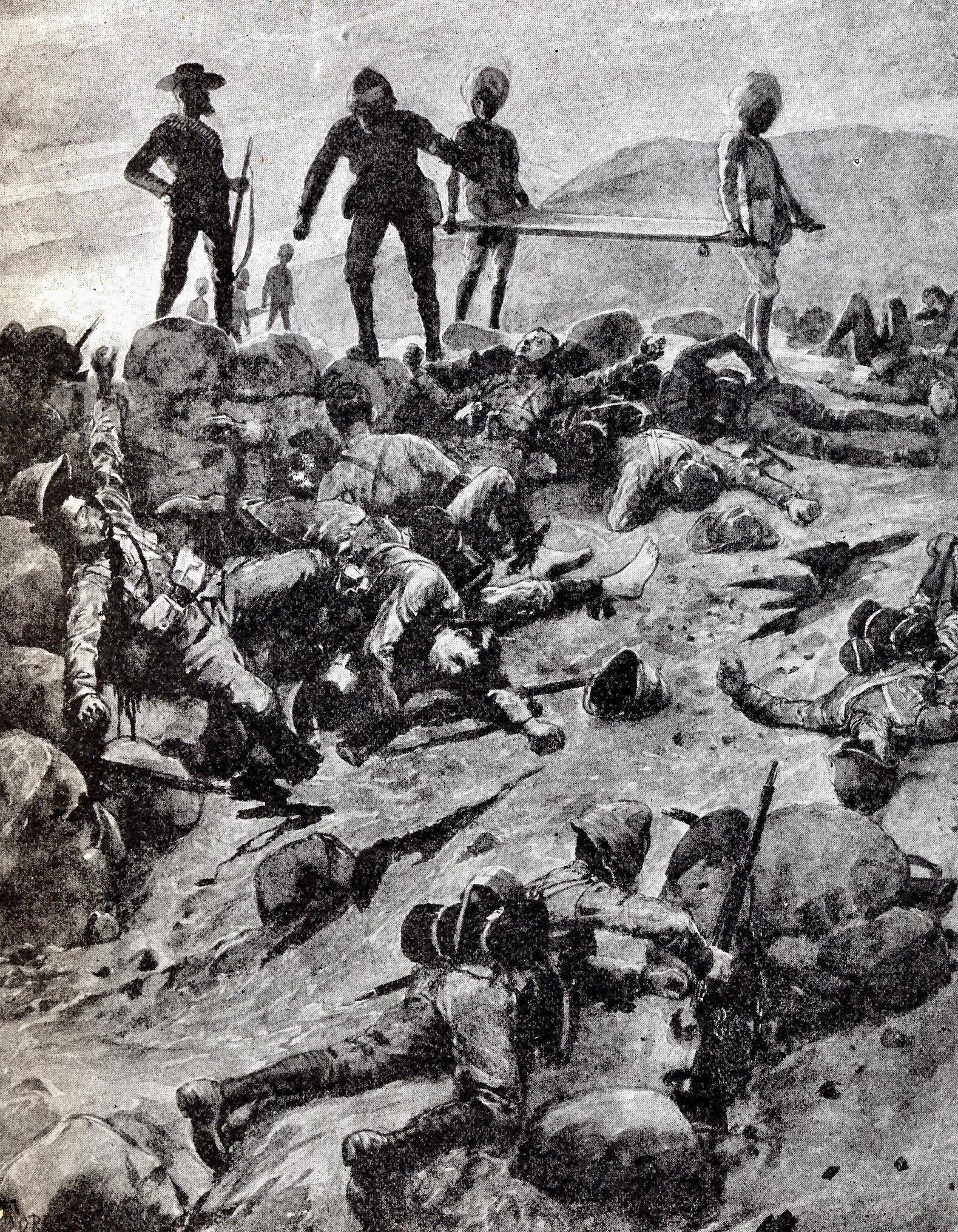

Sketch of Indian stretcher bearers removing wounded from Spioenkop (With the Flag to Pretoria)

On 24 January 1900 the Second Bearer Corps marched from Frere to Spearman’s farm. They were immediately set to carrying the wounded to No 4 hospital’s temporary position at Spearman’s farm – a distance of 6 miles.

In Gandhi’s words from Satyagraha in South Africa (pg 71):

…the British army met with reverse after reverse in the beginning of the war and large numbers were wounded. The officers therefore were compelled to give up their idea of not taking us within the firing line. But it must be stated that when such an emergency arise we were told that as the terms of our contract included immunity from such service, General Buller had no intention of forcing us to work under fire if we were not prepared to accept such risk, but if we undertook it voluntarily, it would be greatly appreciated. We were only too willing to enter the danger zone and never liked to remain outside. We therefore welcomed this opportunity. But none of us received a bullet wound or any other injury.

The corps acquitted itself well. Though our work was to be outside the firing line, and though we had the protection of the Red Cross, we were asked at a critical moment to serve within the firing line. The reservation had not been of our seeking. The authorities did not want us to be within range of fire. The situation, however, was changed after the repulse at Spion Kop, and General Buller sent the message that, though we were not bound to take the risk, the Government would be thankful if we would do so and fetch the wounded from the field. We had no hesitation, and so the action at Spion Kop found us working within the firing line.

Amongst the wounded we had the honour of carrying soldiers like General Woodgate. The corps was disbanded after six weeks' service.

In an account of Gandhi during the Battle of Spion-Kop published in the Illustrated Star of Johannesburg in July 1911, Vera Stent described the work of the Indians as follows:

My first meeting with Mr. M. Gandhi was under strange circumstances. It was on the road from Spion Kop, after the fateful retirement of the British troops in January 1900. After a night’s work, which had shattered men with much bigger frames, I came across Gandhi in the early morning sitting by the roadside – eating a regulation Army biscuit. Every man in Buller’s force was dull and depressed, and damnation was heartily invoked on everything. But Gandhi was stoical in his bearing, cheerful, and confident in his conversation, and had a kindly eye. He did one good… I saw the man and his small undisciplined corps on many a field during the Natal campaign. When succour was to be rendered they were there.

Photographs from the period often lead to confusion, as there were actually three distinct groups of stretcher bearers operating during the war. Very often over the years photographs containing Indian stretcher bearers have been incorrectly captioned as being members of the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps when they were actually RAMC.

"The Indian bearers served a very useful purpose in relieving the RAMC of the time consuming and fatiguing activity of stretcher bearing and thus freed the RAMC for other tasks.” ( J C de Villiers, Healers hospitals and helpers Vol 1, pg 319)

After all that explanation, in my considered opinion, there is no evidence that Gandhi was ever on the top of Spioenkop hill during or after the battle, but he may very well have been carrying wounded from the base of the hill to Spearman’s farm and assisting at the hospital with wounded soldiers who had been transported from the battlefield. He was in the vicinity of Spioenkop but direct evidence of his presence on top of the hill itself, remains elusive.

About the author: Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years, her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. From 1983 to 2021, as curator, Pam developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. She remains a Trustee of the museum and is involved in the finances as well as digitising the considerable archival collections.

References

- The tale of a field hospital, Frederick Treves

- Healers, helpers and hospitals, J C de Villiers

- Satyagraha in South Africa, M K Gandhi

- Talana Museum archives

- Natal Archives -documents of the Public Works Department

- Natal Volunteer Indian Ambulance Corps, AngloeBoerWar.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.