Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Since South Africa’s first professional photographer, Julius Leger, established himself in Port Elizabeth during 1846, both local and international photographers who foresaw commercial opportunities in this newly established art form, as well as missionaries, anthropologists, soldiers, explorers and traders have contributed to the spread of photography into the interior of South Africa.

It is unknown as to how many missionary photographers have been active in South Africa since the commercialisation of photography around the 1850’s. Unlike commercial photographers that made a living from photography and made their work identifiable by applying their names to the carte-de-visite or cabinet card format images, photographic work produced by missionary photographers has largely gone unnoticed as most of their work cannot always be linked to a particular photographer with certainty.

What is certain, is that missionaries who were natural visual recorders of their surroundings, contributed vastly to the visual history of South Africa.

Occasionally images produced by missionaries still surface today. The author, for example, acquired two separate accumulations of such photographic images. These acquisitions led to this article.

Of particular interest amongst these photographic images are magic lantern slides produced by a missionary based in the Kamiesberg area in the Namaqualand, Northern Cape around late 1910, early 1920’s. This missionary was seemingly attached to the Methodist Church. It has been suggested that Methodism was introduced into South Africa as early as 1806.

A magic lantern slide is a small rectangular piece of glass which contains an image with either art work, such as etchings, or photographs. These images were then projected onto a sheet or a wall using a magic lantern (projector). The magic lantern is viewed as the direct ancestor of the motion picture projector.

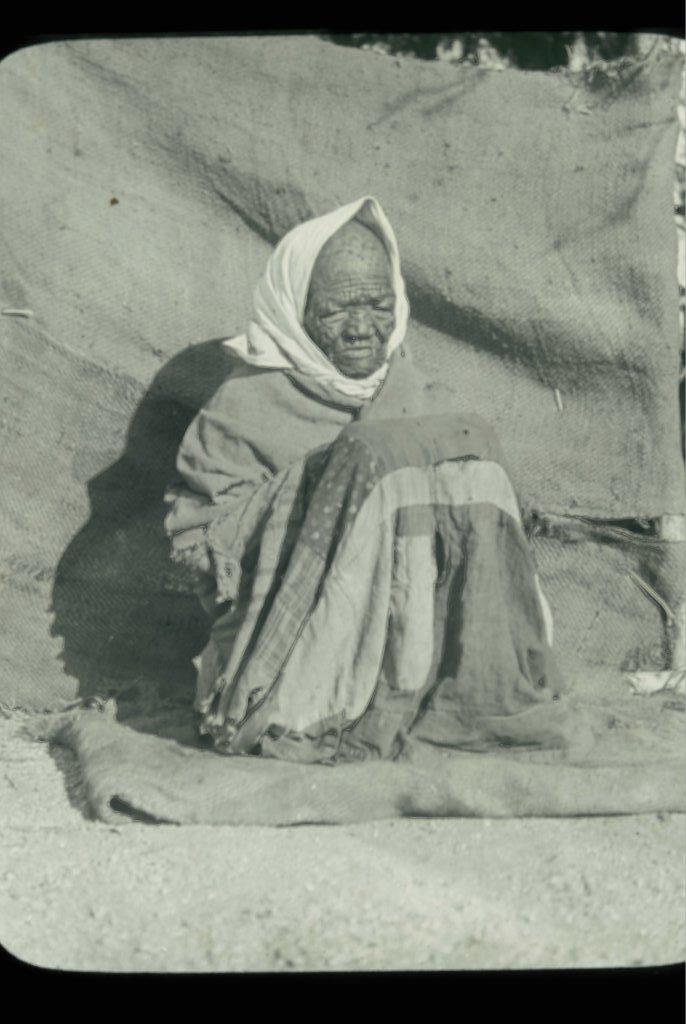

Elderly Namaqua Woman

History of Missionary Photography

One of the most important social movements of the nineteenth century was the worldwide proliferation of Christian missionary activity, devoted to Western evangelism.

Some missionaries compiled valuable visual records of their activities. The number of missionary photographers grew exponentially from the 1880’s, when factory made negatives became available, and cameras became lighter and easier to use. As a result, most missionary societies, or their libraries that hold their archives, have accumulations of photographs in various formats, ranging from uncatalogued boxes or albums to carefully preserved and well organised, and professionally catalogued collections.

Within the South African context it could be argued that the most comprehensive photographic evidence of our diverse cultural history would be those produced by the missionaries who established themselves in the vast expands of South Africa.

The reason for creating photographic images were as diverse as - creating an argument to their principles as to the scale of the evangelistic task at hand - to propaganda (mostly presented from an unintended Eurocentric point of view) - or simply for personal reasons.

With their Eurocentric masks, missionaries entered communities either as constructive participants or sometimes as antagonist, but almost always as curious observers of the indigenous ways. For reasons both practical and religious, missionaries were dedicated correspondents, diarist and record keepers. The many millions of images created by the missionaries is a confirmation hereof.

Missionaries based in South Africa were intrigued by the ethnical composition of the South African society. Their curiosity with the indigenous African way resulted in many photographic images being taken to share with the Western Society, many of them in the format of magic lantern slides in order for the images to be projected at gatherings.

Photography during the earlier years was truly a craft involving many uncertain manipulations of chemicals by hand. The majority of missionaries based in South Africa were using their cameras many hundred kilometres away from larger towns such as Cape Town, developing their images in primitive dark rooms, pretty much the same way the travelling professional photographer would have done in those years.

The majority of images produced by missionaries date from the 1880’s to the 1940’s. It has been suggested that South African missionary photography probably predates that of many other countries as images from around 1860’s are known to exist.

Photographic images produced by missionaries have become a critical resource for research purposes. Although long undervalued, such images now contribute to many research fields such as religious history, social and cultural anthropology and geography to mention a few.

Photographs produced by missionaries not only reflect their experience of the indigenous cultures and the environment they were active in, but also provides examples of the physical and cultural impact the Western influences had on these communities.

Namaqualand missionary photographs

The some 80 lantern slides in the possession of the author include images of fascinating Namaqua people, places and social/religious interaction.

These images include amongst other images taken at Spoeggrivier (near Hondeklipbaai), Bowesdorp, Bailies pass, Swaai and Norap (near Springbok).

Leliesfontein (some 35 km south of Kamieskroon - see main image) is where the Namaqua mission was based, seemingly as early as 1860. Some images show snow at Leliesfontein. About one missionary that settled at Leliesfontein it has been written that “midst of barbarism, the missionary and his heroic wife settled”.

The local Namaqua people recorded on these images are more significant, in that visual records of the turn of the century Namaqua people are not often found. See images of Johannes Wildschut (a Namaqua priest), Johannes Links (a Namaqua schoolmaster) and Mr Peg leg of Okiep (as described on slide). An image of “Flenters”, a boy child, contributes to the social perspective of life at a mission station. “Flenters” loosely translates to, duds or flinders. Although the missionaries would have spoken English, it is clear that they had to incorporate the Dutch language into their daily lives in that the Namaqua's took on the mother tongue of earlier farmers.

Johannes Wildschut, Namaqua Priest

Johannes Links Schoolmaster

'Mr Peg Leg'

The key figure that appears on most of this set of lantern slides is the missionary Annshaw Crampton.

Sadly it cannot be confirmed beyond reasonable doubt as to who the photographer of these images was. The photographer, in all probability was a W Morley Crampton. It is not clear whether Annshaw and W Morley was one and the same person.

In the extensive photographic research collection of the author (On photographers active in South Africa between 1850’s and 1915), not a single missionary photographer has been recorded or confirmed to date, which confirms the immense research opportunities on missionary photographers active in South Africa.

References:

http://www.sahistory.org.za (Photography and the liberation struggle in South Africa);

http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/collections (International Mission photography Archive);

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.