Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Achmat Ebrahim Dangor was born in 1948. The same year in which segregation was enforced through the policy of apartheid. Achmat would witness its implementation and the many atrocities it brought and against which he fought. He also experienced the demise of apartheid and played a key role in building a democratic South Africa whilst pursing creative writing. Achmat passed in 2020. Two years later Audrey Elster, Achmat’s wife and partner of 30 years, initiated the Achmat Dangor Legacy Project (ADLP) and in December 2024, a new website showcasing the work of the ADLP and the life and times of Achmat went live. In this article I will introduces readers to Achmat, and explain the work of the ADLP and its website (click here to view).

Growing up under apartheid and an activist family

Achmat’s parents Ebrahim and Juleigha married at a young age and settled in Newclare, Johannesburg. In February 1946 their first child Mohammed was born. Achmat followed on 2 October 1948. Over the next 18 years the other seven Dangor children were born: Suleiman; Abdullay; Yasmin (Jessie Duarte); Moosa; Igshaan; Abbas; and Zane. They grew up under apartheid and witnessed the full might of the state. Their neighbours were forced to move and their father’s shop forced to close. Their mother became the sole breadwinner and despite struggling, opened the family home to those in need. Six of the nine siblings joined the liberation struggle.

Anti-apartheid work and cultural activism

Achmat won a scholarship from the Institute for Race Relations (IRR) to study literature at Rhodes University in 1970. He juggled many roles and travelled throughout the country. Aligned to the Black Consciousness Movement, he worked with Bantu Steven Biko and other leaders; was a member of the South African Students Organisation; a founding member, with Don Mattera and other writers, of Black Thoughts, a writer’s cultural collective; and was president of the Labour Party’s Youth Organisation. Unbeknown to Achmat, the Security Branch was monitoring his movements and in October 1973, he was issued with a banning order. His studies were terminated, Black Thoughts was banned, and Achmat was banned and confined to Newclare for five years. Achmat found ways of continuing with his writing and political work despite this. A few years after his banning order expired, Achmat moved to Riverlea and soon became involved in civic structures in the area.

By the 1980s, civic structures were formed and there was a vibrant arts and culture community across the country. Both played a key role in the liberation struggle. The Writers’ Forum was established by Achmat and others in 1982. It convened many meetings and discussions centred on the role of the writer. One of the issues that received attention at the “Culture and Resistance” Symposium in Gaborone in 1982 where “People’s culture” was first adopted and “cultural workers” embraced the idea that art should be a weapon in the fight against apartheid.

In the face of growing resistance, the apartheid government announced that a “Tricameral Parliament” would be created. A new kind of resistance began to take shape and the United Democratic Front (UDF) was launched in August 1983. Homes of community leaders became organisational bases including the homes of Riverlea activists such as writer Chris van Wyk, Achmat and Jessie Duarte. In Riverlea, the Anti-President’s Council, of which Jessie and Achmat were key members, worked closely with the Transvaal Anti-President’s Council Committee and the UDF.

It was an unprecedented period of resistance and the government responded with increasing repression. On 20 July 1985, the first of two states of emergency was introduced. It gave the police and the army unlimited power to detain people and to ban meetings; organisations; and books. In response, a group of publishers and writers established the Anti-Censorship Action Committee in 1986. Achmat was a founding member and for many writers political and literary work became intertwined.

Achmat was also part of the Progressive Arts Project which undertook logistical work for other cultural and political organisations. In July 1987, the Congress of South African Writers (COSAW) was formed with Achmat as president of the Transvaal branch. COSAW initiated literary projects; hosted literary events; and published books. It was linked to the UDF which, between 1985 and 1987 (dates vary), established a Cultural Desk and Achmat was a member along with other activists including poet Mzwakhe Mbuli and photographer Paul Weinberg. It organised the “Culture in Another South Africa” (CASA) conference with the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement and the ANC’s Cultural Desk.

Cultural workers returning from CASA were optimistic, but also expected more repression with the on-going State of Emergency. One of the outcomes was the establishment of the National Arts Initiative which campaigned for a non-partisan, representative arts body. In December 1993 it achieved its goals and the National Arts Coalition was formed. It had an influential role initially in arts and culture policy development under the new democratic dispensation.

Development work and human rights activism

Achmat was also an institution builder and strategist. When he was banned, he secured employment (under the Sullivan Principles) as a warehouse supervisor at the American cosmetics company Revlon Inc Johannesburg. He worked there for 15 years ultimately holding the position of Director, Material Management & Planning. Through Revlon he was able to travel and continued with writing and political work. Achmat went on to occupy demanding and high-level positions in a range of organisations and continued writing.

In September 1986, Rev Beyers Naudé asked Achmat to become Executive Director of Kagiso Trust (KT) a position he held till the end of 1991. It was risky work and the apartheid state made repeated attempts to shut down KT by harassing staff and imposing legal constraints. By the end of 1989, it was clear that a change in strategy was needed and under Achmat’s leadership KT transformed from a funder of victims of apartheid to a development agency.

By this time Achmat and Audrey had met and in 1992 headed to New York where Achmat was a Writer in Residence at the City University of New York for three months. He taught South African literature and creative writing. On his return in 1993, Achmat was appointed as Head of the Secretariat of the National Rural Development Fund and developed strategies to help rural communities with drought relief.

In 1994 Achmat was recruited by the Independent Development Trust (IDT) as Director for Rural Development and designed programmes to empower rural communities. As part of the leadership group, the IDT shifted to a more “people-centred philosophy”. He later served as its acting CEO during the transformation period.

In 1998 Achmat was headhunted by Nelson Mandela for the position of CEO at the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund a position he held from October 1998 through to 2001. He led the transformation process repositioning it as a development and advocacy agency committed to promoting community level responses to challenges faced by children and youth and intervening in the HIV/ AIDS arena at a time when AIDS denialism was widespread.

At the end of 2000, Audrey was appointed to manage the African Youth Alliance, a youth sexual and reproductive health and rights programme, based at the UNFPA in New York. The couple relocated and decided that Achmat would focus on his writing. However, not long after they settled Achmat began working with Synergos as a Senior Fellow and was a consultant to the Clinton HIV/AIDS Initiative and UNAIDS and was ultimately Interim Manager of the World AIDS Campaign. From April 2004 he was the Director of Advocacy, Leadership and Resource Mobilisation at UNAIDS in Geneva till December 2006. Achmat refined and implemented global advocacy strategies to respond to changing dynamics which encouraged longer term, sustainable responses to HIV/AIDS among donors and multilateral organisations across the globe.

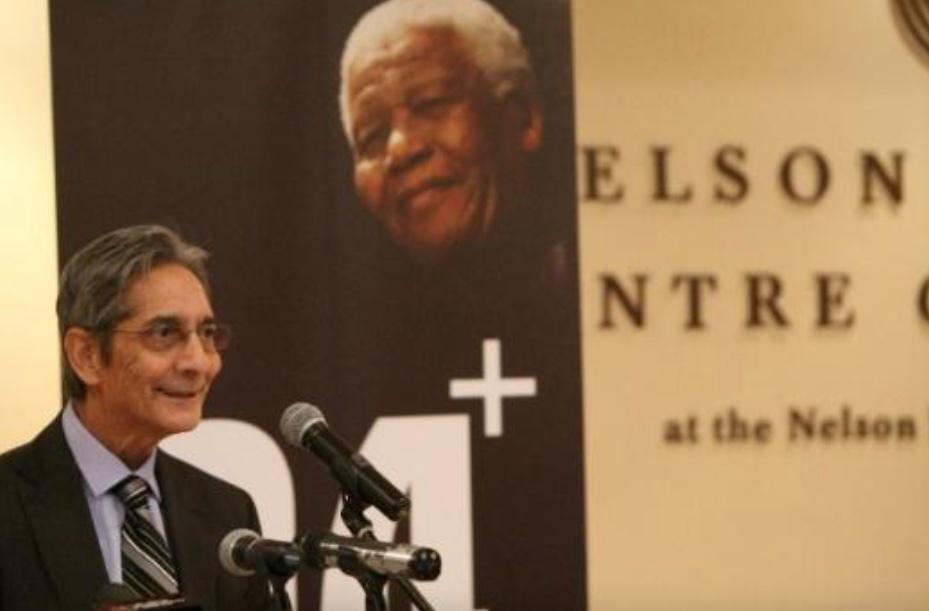

In 2007, at Nelson Mandela’s request Achmat gave up his position at UNAIDS and returned home to lead the Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF). He was there for seven years. Amongst many tasks, Achmat led the implementation of the “Five Year Transitional Plan”; oversaw the refurbishment of the building; and raised the necessary funds to sustain the organisation as it transitioned into the Centre of Memory and Dialogue. The Rural Education Programme and the 46664 Campaign were restructured into separate entities and “Nelson Mandela International Day” was officially recognised by the United Nations.

In 2013 Achmat retired but it was short-lived. He was invited to sit on the Board of Trustees of the Mandela Rhodes Foundation (MRI) and was persuaded to head the Ford Foundations’ Southern Africa office on a short term two year contract. He redesigned programmes and implemented strategies to ensure greater community participation. When Achmat finally retired he focused exclusively on his writing but also served on numerous boards of civil society organisations and supported civil society campaigns. Running parallel to Achmat’s human rights activism and work in the field of development and social justice was his creative writing.

Achmat as CEO of the NMF, 2012 (Gallo Images via Getty / Sowetan / Antonio Muchave)

Creative writing and awards

Achmat published three poetry collections: Bulldozer (1983), Exiles Within (1986) and Private Voices (1992); one play Majiet: A Play (1986); three short story collections Waiting for Leila (1981), Kafka’s Curse A Novella and Three Other Short Stories published (1997) and Strange Pilgrimages (2013), and four novels The Z Town Trilogy (1990); Kafka’s Curse (1999), Bitter Fruit (2001) and Dikeledi: Child of Tears, No More (2017). He drafted numerous film scripts including “Soft Targets” with his friend, filmmaker, Oliver Schmitz and was a special advisor for Staffrider; a trustee of Ravan Press; and a founding patron of the Johannesburg Review of Books.

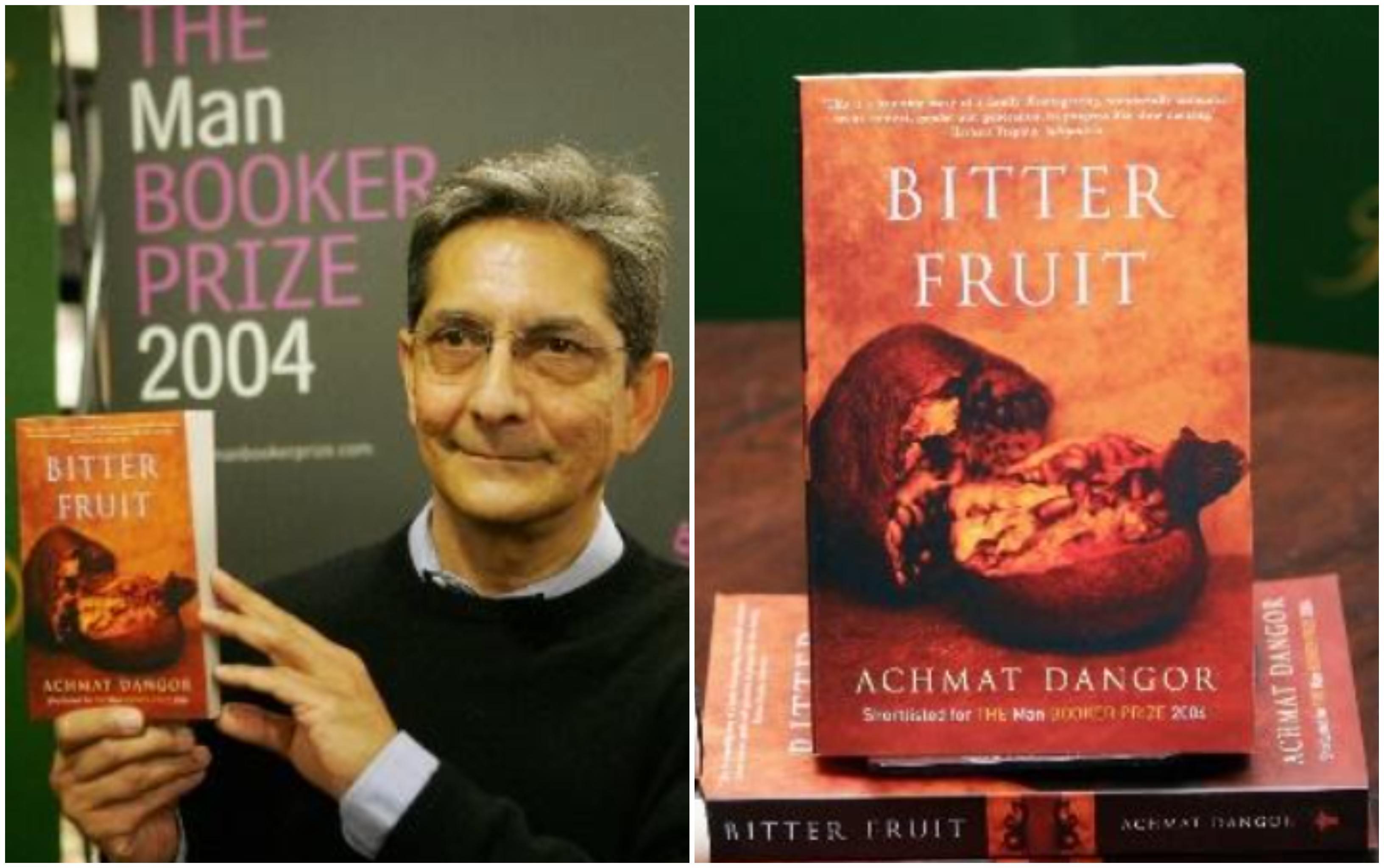

Achmat was the recipient of several awards including the: the Mofolo-Plomer Prize (1979); the BBC Prize for African Poetry (1990); Life Vita Short Story Award (1993); and the Herman Charles Bosman Prize for Kafka’s Curse (1998). Achmat’s book Bitter Fruit was short-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award (2003) and the Man Booker Prize (2004). In 2015 he was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature by the South African Literary Awards.

During Achmat’s retirement he focussed on his “childhood memoir” and although he had made considerable progress it was incomplete at the time of his passing on 6 September 2020.

Celebrating an extraordinary person and sharing Achmat’s legacy

When the news of Achmat’s passing spread messages of condolences poured in. All celebrated his life as an acclaimed author and leading human rights activist. In October 2022, Audrey, inspired by Achmat’s extraordinary life, initiated the ADLP to “inspire others to live life, like he did, to the fullest in the interests of justice, equity and the fulfilment of at least some of the potential that we all have and that he believed so dearly in.”

The project records Achmat’s legacy by: preserving archival items, including oral history interviews, paper documents and photographs, that form part of the Achmat Dangor Papers which are currently being digitised by the NMF after which they will be housed at Historical Papers Research Archives (HPRA) at the University of the Witwatersrand; designing and maintaining the new website; and funding a biennial literary prize in Achmat’s name to support creative writers. The first prize was awarded to Laila Manack in 2023 and the second to Gabrielle Mudiwa in October 2024. Running parallel to the literary prize, research into Achmat’s life was undertaken and interviews with Achmat’s family, friends and colleagues were conducted. The research findings are presented on the new website.

Guests at the announcement of the second Achmat Dangor Literary Prize event, October 2024 (Mandla Sibeko)

Curating and navigating the website

The website was curated by the author with Audrey; designed by historian and creative writer Dr Stephen Symons; and text edited and refined by historian Prof Cynthia Kros. The vision for the website, was to tell the story of Achmat’s life in an accessible way, drawing from archival material that contextualises his life and recorded interviews with Achmat’s family, friends and colleagues who were part of Achmat’s life. The objective is to inspire those who did know Achmat, to learn of his contributions to development and literature; and better understand what he achieved often under very challenging circumstances.

The site presents Achmat’s life as an activist and his work in eight eras. Although reference is made to Achmat’s writing in these eras, the website has a separate section which explores Achmat’s literary life by decade. Achmat’s family, friends and social life are presented in another section and there are brief profiles of the interviewees. As far as possible Achmat’s life story is narrated by himself, using extracts from interviews conducted by scholars and journalists across his life and from articles penned by Achmat. It is much more than a biography of Achmat’s life, it is multilayered and includes multiple voices in the presentation of Achmat’s life by presenting the memories shared by interviewees across the site. It outlines the role that cultural workers; civic associations and NGOs played in contributing to the demise of apartheid and offers institutional histories of the organisations where Achmat worked. It includes an overview of literary developments and the challenges authors and publishers overcame in apartheid times and their role in a democratic country.

The curated content is replete with resources including videos and archival material from collections housed at Digital Innovation South Africa; HPRA; the NMF; South African History Archive; UNAIDS; and the United Nations. The site exhibits over 550 photographs some of which were donated by acclaimed photographers such as Paul Weinberg; Omar Badsha; Paul Botes; Gille de Vlieg; Victor Dlamini; Gideon Mendel and the late Jürgen Schadeberg; and Achmat’s family and friends.

Achmat’s life story reminds South Africans of our shared turbulent history and our capacity to catalyse change. As Achmat once said: “We must remember the past, but without letting ourselves be held back by it, and we must free our imagination … Think about what you can do to make the world a better place” (Achmat Dangor, “My hope for Africa”, 2010).

Left: Achmat at the 2004 Man Booker Prize (Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images via Gallo). Right: Achmat’s Bitter Fruit on display at the 2004 Man Booker Prize for Fiction. (Gareth Cattermole / Getty Images via Gallo)

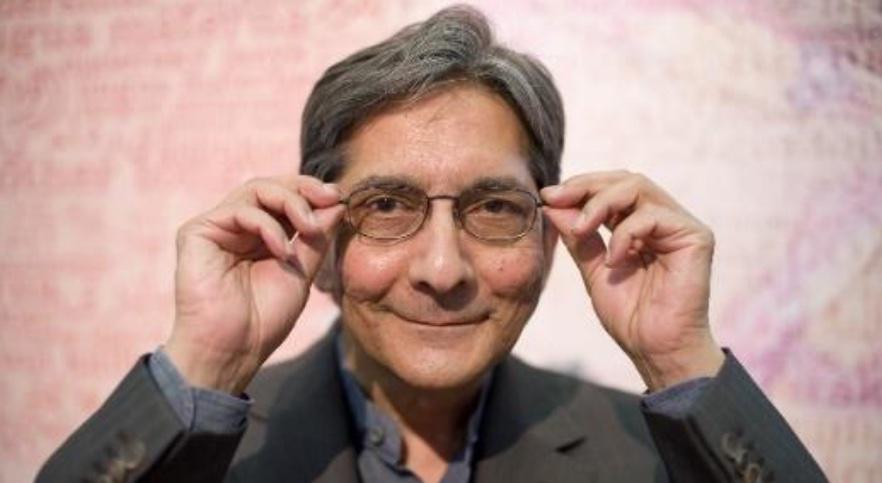

Main image: Portrait of Achmat taken in Udine, Italy, 2006. Leonardo Cendamo / Getty Images via Gallo

About the author: Dr Katie Mooney is a freelance historian, researcher, curator and heritage practitioner based in Cape Town. She is an associate member the History Workshop at the University of the Witwatersrand and can be contacted at: katie@delve.co.za or katiemooney@hotmail.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.