Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Below is the sixth part of John Lincoln's series on the history of Cullinan (click here to view the series index). It looks at some impressive mining history and reveals the vast scale of operations at the Premier / Cullinan Mine. As always, the photos from the Cullinan Mine Archive are remarkable.

To further facilitate the supply of water to the mine, a shaft was opened on the site of a borehole, which struck water at a depth of 300 feet (90 metres) and the water continued to flow out to the surface thereafter. The dimensions of the shaft were 14 feet (4 metres) and 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 metres) and during 1904 it was sunk to a depth of 195 feet (60 metres). It was situated in the north-west corner of the pipe, in blue ground, which looked very promising and pulverised freely. At this depth the shaft was making 600 gallons per hour. It was the intention to sink the shaft to 300 feet, where the water had been struck.

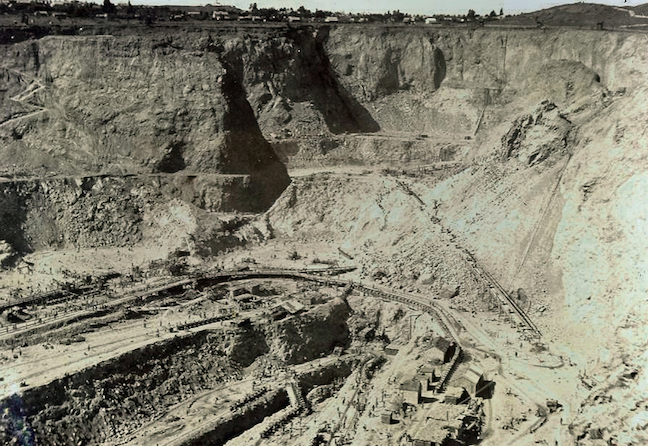

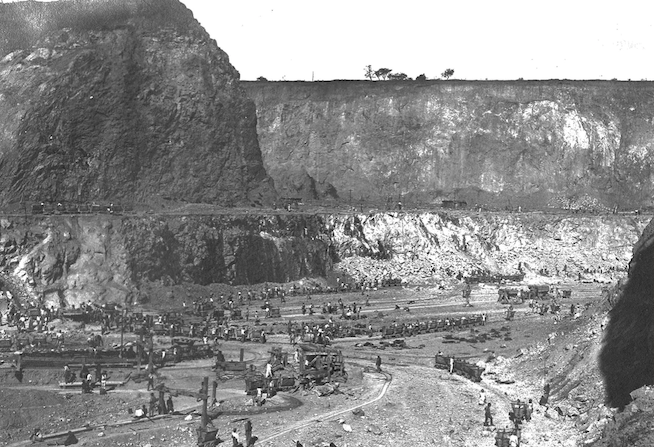

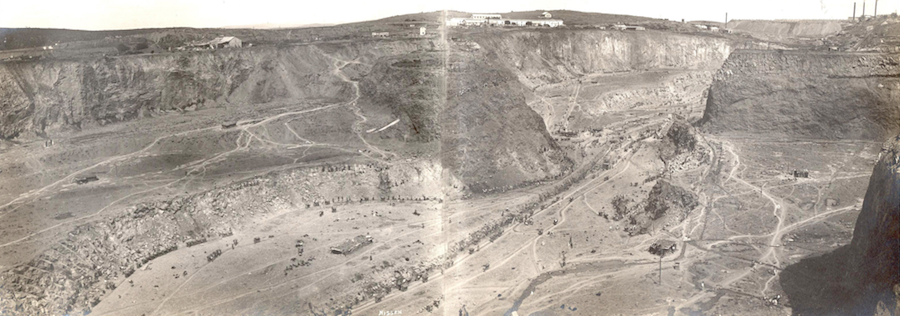

By 1903 a level of 40 ft. had been attained in the open pit. In 1908 a level of 160 feet (50 metres) was being worked and when the mine closed for the first time in 1914 the depth of the mine was 310 feet (100 metres). By 1918 it had increased to 410 feet (125 metres).

Open pit looking west with Nos 2 and 3 headgear on the skyline (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Shaft sunk in 1904 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

The yield of the Premier Mine in 1913 was about 20 carats to 100 loads (25 carats per 100 tons), the average value per carat being 24/- (R2-40). A load of ground was therefore worth 4s 9d (R0-50). Working expenses varied slightly with the season of the year and the supply of labour.

With the great bar of floating reef removed, it was considered that conditions at the Premier Mine would be exceptionally favourable for deep open mining; firstly, because of the resistant nature of the country rock, felsite and quartzite and secondly because of the great area of the pipe.

The actual depth likely to be attained would depend not only on the stability of the pipe walls, but on the maintenance of the grade of blue ground and the price of diamonds.

NW workings with Mine View houses in the background. These houses still remain. (Cullinan Mine Archives)

West mine open workings with east mine in the background, January 1911 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Haulage between east and west mines, January 1911 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

East mine from the west, January 1911 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

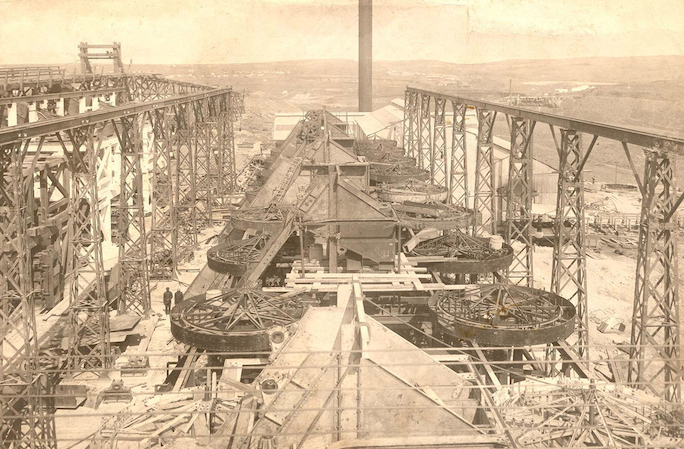

Numbers 3 and 4 Gears

The following was extracted from a newspaper of 1909:

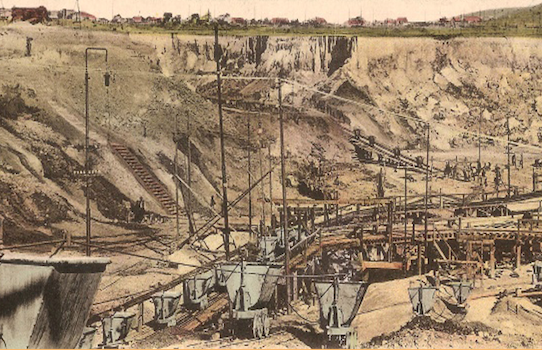

Method of Treatment. The following is a description of the method of washing ground by what is known as the direct double treatment system. The ground is hauled up from the mine by means of a mechanical haulage to the apex of the incline, at which point the trucks disengage from the wire and gravitate along the bridge, being tipped automatically as they pass each of the grizzleys or receiving hoppers.

After passing the last grizzley, the trucks are “righted” automatically and re-engage on to the return wire to the mine.

When the ground is tipped into the grizzleys, the bars of which are set 2½ inches apart, the finer ground passes between these bars through two sets of four-foot corrugated rolls, and is joined by the coarse ground after it has been reduced by the gyratory crushers.

The four-foot rolls reduce the ground to seven-eighths of an inch, and thence it falls to the elevator pit. From this point then the whole of the ground is elevated and discharged into a four-way hopper for distribution to the top pans. In the pans the ground is carried round by means of revolving arms fitted with triangular teeth set in the form of a spiral.

These teeth force the diamonds and other heavy deposit with which diamonds are associated to the outside edge of the pan, the lighter material flowing out at the discharge, situated on the inner rim. The discharge from the top pans passes through a set of six-foot smooth rolls, which finally reduce the ground to 3-16 inch, and thence into the bottom pans, the overflow from the bottom pans to the tailings elevators, which discharge the waste ground in the valleys below the machine.

Arrangements are made to extract the heavy deposit from the pans continuously, one load of deposit being obtained for every 100 loads. This deposit is conveyed to the pulsators, where it is classified and gravitated, about 75 per cent of the lighter material being discarded and the remainder, which comprises the heaviest of the deposit with the diamonds, passes over the grease tables.

The diamonds, together with a very small proportion of concentrates, adhere to the grease tables, the remainder of the concentrates passing over the plates to the “dump.” The plates are cleaned at intervals, and the deposit separated from the grease by means of a boiling process. The deposit is then placed on the sorting tables, where the diamonds are picked by hand.

Up to 31st October 1909, 27,508,044 loads of ground had been treated by the combined gears, from which diamonds weighing 8,435,208 carats have been recovered to the value approximately of ₤7,790,000.

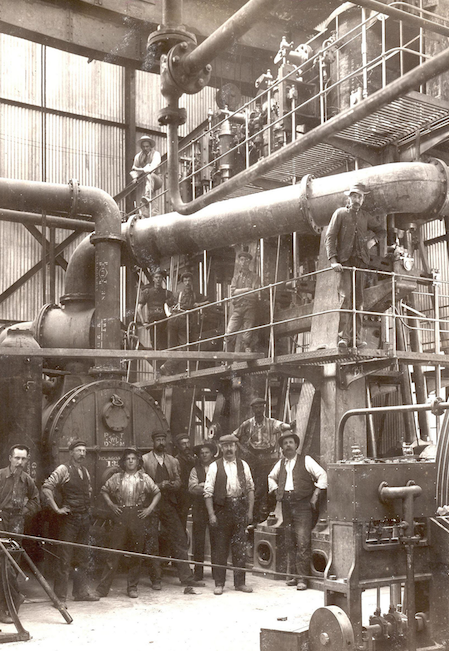

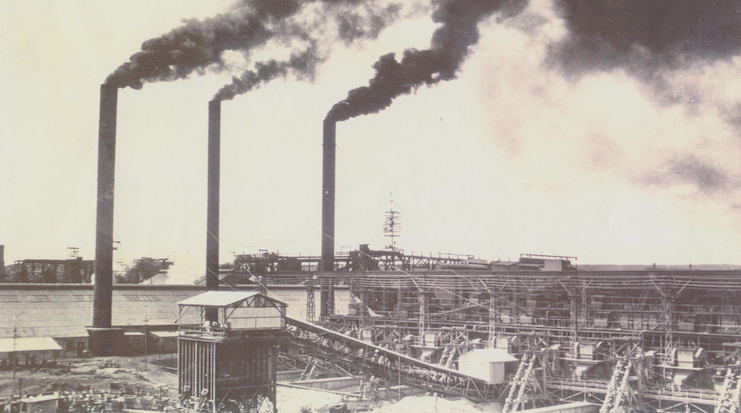

Power station built to drive Nos 2 and 3 gear (Cullinan Mine Archives)

No. 3 gear (Cullinan Mine Archives)

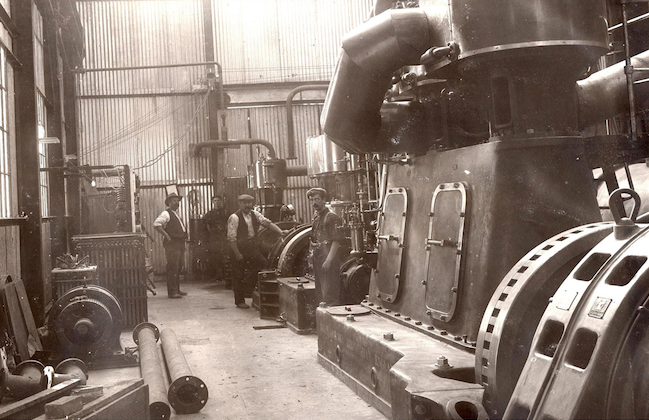

Interior No. 3 gear engine room (Cullinan Mine Archives)

General view of No. 3 gear in 1912 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

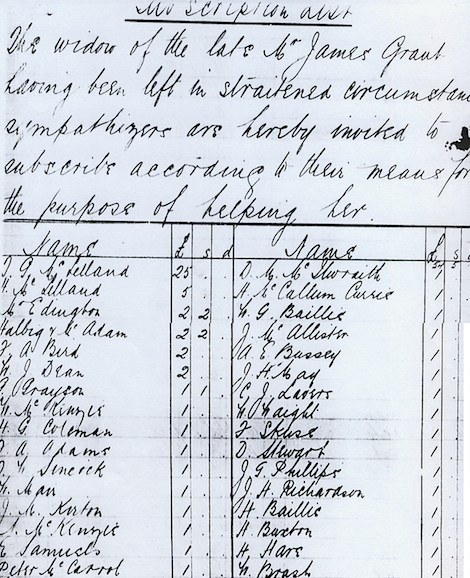

During the construction of No. 3 gear an accident occurred and an engineer on contract from Scotland was killed.

His name was James Grant and he is buried in our cemetery. After the accident his fellow workers made a collection for his widow who was still living in Scotland and found herself left in “straitened circumstances.” They collected ₤138.8.6 and the company also donated an additional two hundred Guineas.

The construction workers on No. 3 gear (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Nos. 2 and 3 gear (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Contributions to the widow of James Grant (Cullinan Mine Archives)

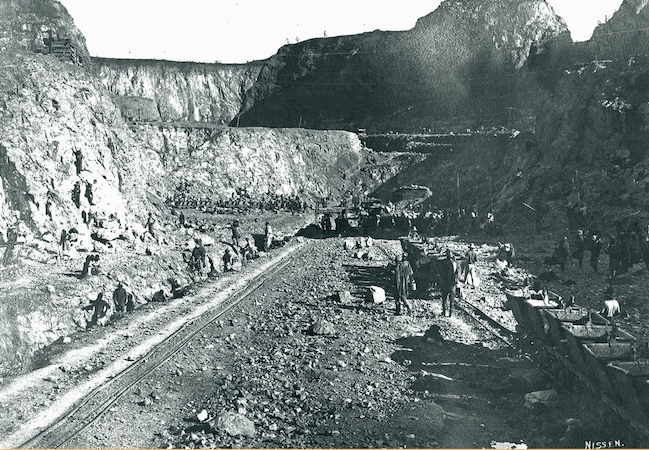

Haulage and Drilling

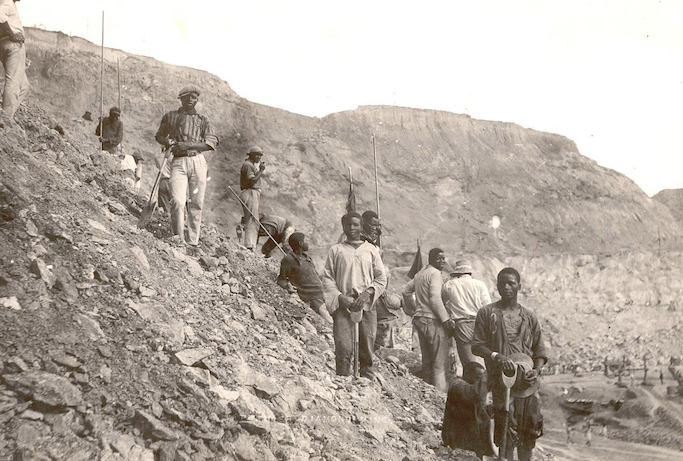

The Premier blue ground was much jointed and fissured, and the effect of the explosives was to rend it into huge lumps and slabs, which had to be re-broken before they could be handled by the loading men. At one time all moiling and drilling of lumps was performed by hand, and 350 men were thus engaged per shift.

The efficient and economical handling of the enormous quantities of blue ground, broken on the working benches, was at one time one of the most serious problems with which management was confronted. Steam and electric shovels were tried in the upper levels of the mine, but it was found that as far as costs were concerned, these machines could not compete with hand labour, and this method was scrapped after being in use for about one year.

At one stage very little water found its way into the mine through infiltration, but a lot of trouble was caused during the summer months through heavy downpours of rain. This was hardly surprising when one remembers that every inch (25mm) of rain, over the pipe area, represented a volume of 285 00 cubic feet (8 000 cubic metres). Suitable steps were eventually taken to cope with the rain water problem.

The “bete noir” of the Premier Management at one time was the great bar of “floating reef:” and the removal of this gigantic obstruction was vigorously carried on for some years. During September 1913, an average of 4623 men were employed in the mine per shift. The average quantity of ground broken per drill worker per shift was from 9 to 10 loads (7,2-8 tons), and the quantity loaded per loading worker was from 12 to 13 loads (9,6-10,4 tons).

Drilling and shovel work, 1909 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Onsetting station, June 1909 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

View of the open pit looking west in 1912 with, left to right, first compounds, No. 2 gear, No. 3 gear on the skyline and the stores and village to the right (Cullinan Mine Archives)

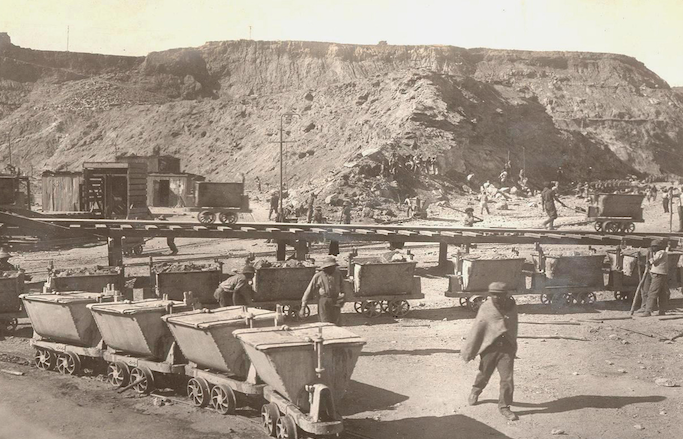

Nos 3 and 4 haulage. Both produced from a postcard.

View of the open pit looking south west in 1911 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Workers loading coco-pans (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Looking north-east, January 1909 (Cullinan Mine Archives)

When the mine closed in 1932 a report called the Resumé of Operations from the Inception of the Company was produced. A snippet from that report reads:

In 1914, the services of 381 European employees who had taken an active part in the industrial disturbances which then prevailed were discharged, and in August 1914, following the outbreak of hostilities in Europe, the Mine was closed down when the services of practically all the Europeans, numbering 794, were dispensed with and the labour force of 14,500 natives repatriated. Relief work was subsequently found for some 300 Europeans for a period of four months when they were discharged, with the exception of 54 who were retained for the purpose of guarding the property and maintaining the essential services.

Letter written to management on the 12/07/1914:

Dear Sir

Pardon the liberty I take in addressing you by letter and may I beg of you to let me know if there is any truth in the rumour that the company are not taking over the houses [in thoses days many of the houses were privately built). If so then I do not know what I am to do. I am a private nurse with a mother and a sister depending on me. I have just invested £350 at the time of the last strike on the mine buying a house and since buying it have spent £20 in having it finished. That is all I possessed, all my savings for the past 18 years, my object for investing in a house being that I might be sure of a little no matter what happened. I am alone in this community and as the community is over-run with nurses I may have to wait some months before I can work up a connection again. If only the company will take over the houses then I will be able to go elsewhere and make a start. I am sure a rich company such as this cannot be so inhuman. Thanking you in anticipation of receiving a favorable reply.

I remain

Dear Sir

Nurse Creedon

It is unknown what happened in the above case, but it was the policy to take over private houses when residents left the property.

Some of the privately built houses and rondavels of the early days (Cullinan Mine Archives)

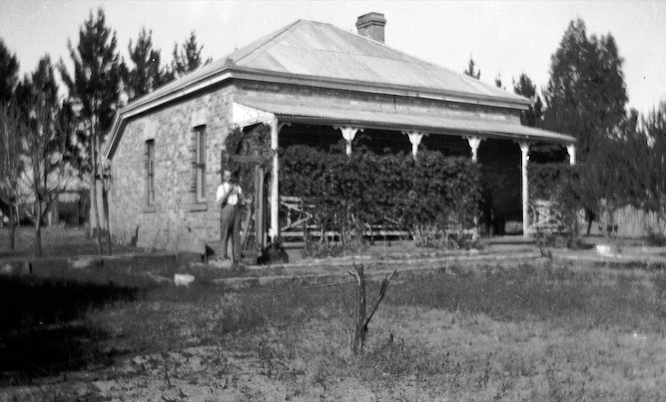

Company built house at Wilge River (Cullinan Mine Archives)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.