Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is unusual for a middle-class British couple to be celebrated for their respective achievements over half a century. The female partner in this relationship, Dame Agatha Christie, Britain’s bestselling author since Shakespeare requires little introduction. Her husband, the late Sir Max Mallowan, an eminent archaeologist who excavated several important sites in the Middle East, may be somewhat less familiar. While accompanying him on archaeological excavations in the Middle East, Agatha Christie worked on several of her murder mysteries, such as Murder in Mesopotamia, Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile and Appointment with Death, all set in this historic region.

Like many others, I learnt of Agatha Christie at my late mother’s knee. It therefore seemed appropriate to share some aspects of their unusual lives, blending murder mysteries and archaeological excavations.

Agatha May Clarissa Miller was born on 15 September 1890 on the outskirts of Torquay. Her father Frederick Miller was a successful American businessman but died when she was only eleven years old. The youngest of three siblings, she was devoted to her mother, Clara. Writing must have been in the family’s blood as her older sister Madge also authored several books. Perhaps due to straightened circumstances because of the death of her father, Madge was sent to board at Roedean School, while Agatha was home schooled by her mother and a succession of governesses. Possibly the mother might also have considered the hurly burly of boarding school too much for the sensitive Agatha. Unfortunately, this lack of contact with other children caused Agatha to become unusually shy and introverted. At one stage she attended singing lessons in Paris and considered becoming a professional opera singer, but her voice was not strong enough and she had to abandon her aspirations in this field. She also contemplated becoming a professional pianist, but here her music master thought her too nervous to perform in public.

Agatha Christie (Wikipedia)

Having been engaged since 1912 to Archie Christie, a young military officer, they married soon after the outbreak of the First World War. With his going to war with the Royal Flying Corps, she elected to serve with the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in a Red Cross hospital in Torquay. Later she transferred to the dispensary where she gained useful knowledge of various medicines and poisons. At the same time, she had opportunity to observe some Belgian refugees accommodated near Torquay.

To relieve the monotony of serving in the dispensary Agatha Christie set out to meet her sister’s challenge to write a murder mystery, applying her love of Sherlock Holmes and storytelling, a casual acquaintance with Belgian refugees and working knowledge of poisons.

The post war years started off well with Archie returning as a Colonel in the Royal Air Force, followed by the birth of their daughter Rosalind in 1919. In the same year, further good news arrived that the fourth publisher they approached, John Lane of the Bodley Head was willing to publish her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Lane insisted on changing the final chapter though, replacing a court room climax with the now familiar revelation in the library. When published in 1920 it sold 2 000 copies.

Book Cover

It introduced Hercule Poirot, the cerebral little Belgian detective with the uncanny ability to crack complex murder cases. The murderer’s use of poison was so well described that a review from the Pharmaceutical Journal, applauded ‘this detective story for dealing with poisons in a knowledgeable way, and not with the nonsense about untraceable substances that so often happens. Miss Agatha Christie knows her job’. Now a century later, Styles remains an entertaining plot, worth reading even if only to be introduced to Hercule Poirot and his foil Hastings. Hastings played the role originally paved by Watson in the Sherlock Holmes series, and regularly appeared with Poirot, until Agatha apparently wearied of his somewhat doltish ways banished him to Argentina.

In 1922, leaving Rosalind with her nurse and mother, she and Archie travelled across the then British Empire, promoting The Empire Exhibition of 1924. Stepping ashore at Cape Town they travelled to the Kimberley diamond mines, before proceeding through the Matopos to the then Rhodesia to visit Salisbury (now Harare) and Livingstone, where she saw her first crocodiles. Then a quick trip to the Victoria Falls that left a vivid impression, and returning via Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Durban. In Cape Town she and Archie took time off whenever they could by taking the train to Muizenberg where they enjoyed the surfing. From Cape Town they sailed to Australia and New Zealand, stopping over for a holiday in Hawaii before embarking on the last leg through Canada.

Surfing at Muizenberg (Agatha Christie Archive Trust)

Although Agatha Christie said she did not seriously contemplate becoming a professional author until she had sold five or six books, she derived both pleasure and a reasonable income during the early 1920’s from her writing as she published approximately one book per year. The couple named their house at Sunningdale Berkshire, ‘Styles’ after her first novel and Agatha Christie enjoyed owning her first car, a bullnose Morris Oxford.

Her sixth murder mystery, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd published in 1926 proved an instant success. Five and a half thousand copies were printed by Collins and over 4 000 copies were rapidly sold, then considered a very good sale. It is often claimed that Lord Louis Mountbatten suggested the plot to her. In any event, here Agatha Christie conceived the unusual idea for the time, of having one of the central characters considered above suspicion, exposed as the murderer.

Shortly thereafter Agatha Christie’s mother died, and she might have sensed the impending break up of her marriage. To her dismay she was becoming a golf widow before Archie suddenly revealed he was in love with a fellow golfer and an acquaintance of hers, Nancy Neale.

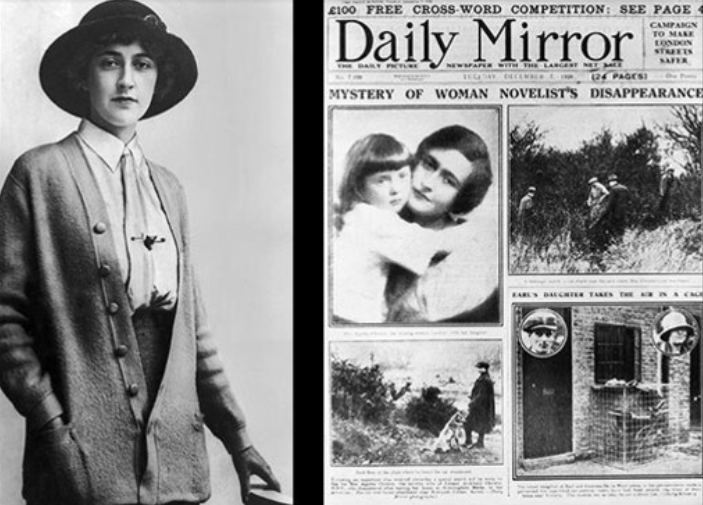

The photo on the left shows Agatha Christie in 1925 (Wiki Commons)

Theirs must have been one of many marriages that failed to survive the enforced separation brought about by the war and the gradual growing apart due to diverging interests, his golf, and her writing. Perhaps, the two incidents, together with the strain of constant writing, proved too much for her inventive mind to cope with and manifested in a strange way. In 1926 an extraordinary event occurred. Perhaps suffering an episode of amnesia possibly due to the onset of severe depression, she walked out of her life one afternoon, abandoning her Morris car in a field several miles away.

A hue and cry in the press followed, with the Daily News even offering a £100 reward for any information regarding her disappearance. Soon a banjo player in the band at the Hydropathic Hotel at Harrogate informed the police of his suspicion that a Mrs. Theresa Neele, ostensibly from Cape Town who had been staying at the hotel for nine days was, in fact Mrs. Christie. Strangely, the surname she registered under proved to be that of her husband’s mistress. The other guests at the hotel who had all been charmed by Agatha Christie’s behaviour agreed that she was obviously suffering from memory loss. It is also possible that feeling deeply betrayed by her husband, and so to punish him, she created the perception of a possible suicide. In 1928, following a futile attempt to reconcile their differences, the couple agreed to a divorce, allowing Archie to marry Nancy Neele shortly afterwards. With little money, Agatha must have decided she needed to produce books at regular and frequent intervals to earn an income.

In 1929 Agatha decided she needed a break from writing. After arranging with her travel agent to visit the West Indies, she changed her mind at the last moment and instead ventured to Baghdad. A chance conversation with a couple at a dinner party persuaded her to visit Baghdad, the River Tigris and the ancient cities being excavated there. When they mentioned she could travel there on the Orient Express she became very interested as travelling on this famous train from Calais to Istanbul had always been one of her desires. In Baghdad she fell into the company of a ‘lobster of a woman’, a figure who would reappear in many of her novels. Desperate to escape from her claws, Agatha on slight acquaintance called on Leonard Woolley who ran the combined British Museum and Museum of the University of Pennsylvania excavation at Ur. Ur, about halfway between Baghdad and the head of the Persian Gulf had been excavated by Woolley since 1922.

Ziggurat at Ur being uncovered. Built by Ur-nammu about 2100BC (Wiki Commons)

Fortunately for Agatha, Woolley’s formidable wife Katherine (1888-1945) was a Christie fan having just read The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and she invited Agatha not only to stay until the end of the dig, but to join them again the following year. This was quite an achievement since although Katherine was a gifted woman of great charm, she could also be very moody. Max Mallowan described her as a domineering and powerful individual, feline in nature and quoted Gertrude Bell the great Middle East traveller’s description of her as a ‘dangerous woman’. Agatha immediately accepted the invitation, where she was soon to meet her future husband Max Mallowan (1904-1978), one of Leonard Wooley’s young assistants.

It must have been an exciting time for Agatha to be present at Ur. The impressive ziggurat, or staged temple-tower, erected in 2100 BC had only recently been uncovered. Originally about ninety feet high, Max described it as having no equivalent in all of Mesopotamia, because of the red rich colour and unmatched composition of the brickwork and the magnificently contrived arrangement of the entire structure with its triple staircase of a hundred stairs apiece.

Woolley was also busy excavating tombs in the Royal Cemetery, which brought forth a wealth of Sumerian treasure of which the beautiful dagger and its intricate sheath illustrated below, is merely one example.

Golden dagger with handle of lapis lazuli, adorned with golden studs and lattice-work sheath discovered in a royal tomb at Ur (Wiki Commons)

The French archaeologist Roland de Mecquenem was so overcome by the beauty of this dagger and sheath that he refused to believe they were 4000 years old, and instead thought Italian craftsmen from the Renaissance period must have made them.

At the conclusion of the 1929-30 digging season, Katherine Woolley virtually ordered Max to conduct Agatha on a round trip to Baghdad, to see the desert and some of the places of interest. He soon found Agatha to be ‘an agreeable person and the prospect pleasing’. After visiting the Abbasid Castle of Ukhaidir on a boiling hot day they decided on a whim to go for a swim in a nearby salt-lake, where their car got stuck in the mud. Max was amazed that Agatha did not reproach him for his poor driving, as Katherine would have done. There and then he decided Agatha was a wonderful woman. They travelled home together initially on the Taurus Express after accompanying the Woolley’s as far as Aleppo where they parted company from them. At Istanbul they transferred to the Orient Express. Max described their train journeys at the end of March as wholly enjoyable that gave him the firm intention of seeking Agatha’s hand when they reached home. The pleasant train journeys across interesting cities and beautiful scenery could only have strengthened his determination to marry her. Initially reluctant to marry someone so much younger than herself, although they had much in common, it was only when her daughter Rosalind persuaded her to do so that they married on 11 September 1930, at the small chapel of St Columba’s Church in Edinburgh. So began a productive and recurring annual writing and travelling routine for the newly married couple. Summers at Ashfield with Rosalind, Christmas with her sister’s family at Abney Hall in Cheadle near Manchester, late autumn and spring on excavations and the rest of the year in London and from 1939 onwards, at their summer house Greenway on the River Dart in Devon.

Unlike her first marriage, this one was to last for 46 happy years until her death on 12 January 1976, at the age of 85 years.

A young Max Mallowan (Wiki Commons)

Perhaps it is now appropriate to introduce Max Mallowan. Upon graduation from Oxford University in 1925, Max was asked by the Dean what plans he had for the future. Responding he would probably enter the Indian Civil Service or perhaps pursue law since his father disapproved of a commercial career, the Dean enquired what would he really like to do. Max promptly responded with one word only, ‘archaeology’. The Dean then referred him to the Warden who in turn gave him a letter of introduction to D. G. Hogarth, Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. Fortuitously, Hogarth had that very morning received a written request from Leonard Woolley for an assistant to help at the excavation of Ur. Max added that Woolley always in a hurry, practically engaged him on sight, despite his total lack of experience; partly because he was not bumptious and partly because his tutor Stanley Casson, had sent Woolley a kindly letter.

It is interesting how many of the eminent British archaeologists of the early 20th century, at some stage or other touched the lives of Max and Agatha: Hogarth, Woolley, and even Howard Carter of Tutankhamun fame. In 1910 Hogarth directed the important excavation at the ancient Hittite city of Carchemish under the patronage of the British Museum. At his suggestion T. E. Lawrence (the later and famous Lawrence of Arabia) was appointed Archaeological Assistant. When Woolley succeeded Hogarth at Carchemish, he and T. E. Lawrence also worked closely together. Early in 1914, Woolley and Lawrence completed an archaeological survey of the Wilderness of Zin in the Negev Desert on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. This survey reputedly served as a cover for the British Army to map the region bordering the Suez Canal in the event of war with the Ottoman Empire. One can imagine Woolley sharing some of Lawrence and his exploits with the couple over dinner. In Mallowan’s Memoirs he recalled their 1931 visit to the Tomb at Luxor where the couple befriended Howard Carter, whom he described as a sardonic and entertaining character with whom they played bridge at the Winter Palace Hotel.

It was a fortunate introduction to archaeology for the young Max as Sir Leonard Woolley (1880-1960) was one of the first archaeologists who excavated in a modern way, keeping records, and using them to reconstruct ancient life and history.

Max fully appreciated and enjoyed working for someone as dedicated and knowledgeable as Woolley for the six seasons lasting from 1925 to 1931, even though he found him a hard task master. During his last season he sorely missed the presence of Agatha but wisely realised with the presence of Katherine Woolley, there was room for only one woman at Ur. Interestingly, Katherine Woolley bore an uncanny resemblance to the murdered wife of the archaeologist in Death in Mesopotamia, but fortunately she did not recognise her own personality traits imparted to the victim.

Having assisted Woolley for six years, Max felt he needed new experience elsewhere and thus when Dr Campbell Thomson (1876-1941) the epigraphist, invited him to assist at Nineveh, he immediately accepted.

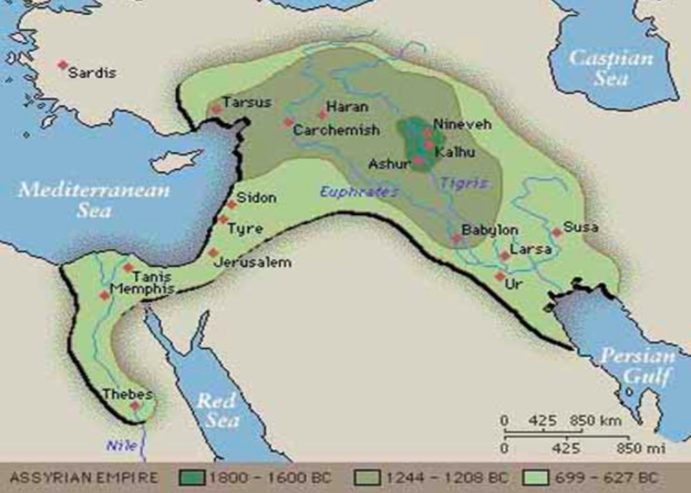

Assyrian Empire (Wiki Commons)

For Max the countryside surrounding Nineveh, in the same latitude as Baghdad, was a paradise compared to the windswept dusty plains of Ur. Lyrically he described how from the mound of Nineveh, he was able to look over to the west at the banks of the swiftly flowing Tigris and across it to the mosques and churches of the city of Mosul, passed by Xenophon and his army of 10 000 Greek mercenaries on their epic march in 401 BC from the plains of Cunaxa to the Black Sea. To the east he gazed into Kurdistan and the snow-capped mountains known as the Jebel Maqlub and behind it the Zagros Mountains which separated Assyria from its dangerous enemy, Persia.

Not only was the countryside a great change, so was his new chief, the bluff and hearty Campbell Thomson, and his delightful wife Barbara. One of the requirements to be selected as an Archaeological Assistant was good horsemanship. This was because Max’s predecessor R. W. Hutchinson, had lost much face with the local workmen by falling off his horse in their presence. Max initially rather uncertain of his riding ability, soon improved his horsemanship to such extent that Campbell Thomson paid him the compliment of saying he rode like a centaur.

Unfortunately, Nineveh or more accurately the mound of Quyunjik, was an untidy one. It had been plundered during the previous 2 000 years and the ground had been churned over again and again. Even worse, generations of plunderers had worked through long tunnels which appeared above Max and his workmen as their pit deepened. There was always the fear of a disastrous pit collapse, but through benevolent providence and careful excavation, fortunately no mishap occurred.

Nineveh mound (Wiki Commons)

Mallowan’s main complaint was that the excavations consisted for the most part of a glorified tablet-hunt for fragments of the great Quyunjik library, which Campbell Thomson greatly prized. Nevertheless, Max admired Campbell Thomson for his various talents rating him much more than merely a specialised epigraphist. He had an amateur interest in botany, geography, and chemistry and with his specialised work on these subjects was able to add much knowledge of Assyriology.

Like most archaeologists of that period, Campbell Thomson was very parsimonious with the expedition’s funds and he considered it a great extravagance when Agatha wanted to buy a table at the local bazaar on which to type her new book. The table cost £3, which Campbell Thomson considered excessive and was quite unable to understand why an ordinary packing case would not suffice as a working surface for her typewriter.

Max was delighted by a discovery of Campbell Thomson’s at Nineveh of a magnificent life-sized bronze head. Max ventured to identify this head, one of the prized exhibits at the National Museum of Iraq, as that of Sargon founder of the Akkadian dynasty.

Bronze head possibly of Sargon, founder of the Akkadian dynasty (Wiki Commons)

He described this famous head as solid cast, probably by the lost wax process, which illustrated a man with Semitic features, heavily bearded and elaborately hairdressed in the style of one of the golden wigs at Ur.

At some point in antiquity the head was vandalised, with the left eye socket badly gouged, the tip of the nose flattened, the ears knocked off and the beard damaged. One could only surmise this happened sometime after the collapse of the Akkadian dynasty.

Sadly, this remarkable bronze head is rumoured to have been looted from the Museum during the Iraqi disturbances of 2003.

Following the completion of his apprenticeship at Ur and Nineveh, Max progressed to conducting excavations of his own at Arpachiyah in Iraq, then Chagar Bazar and Tell Brak in Northern Syria, and finally at Nimrud in Northern Iraq.

In Agatha Christie’s delightful and rather self-effacing little booklet, Come Tell Me How You Live, written in response to this often-asked question of life on an archaeological expedition, she described some of the difficulties she encountered at Chagar Bazar.

Book Cover

Once the lights in their rented house were switched off swarms of mice emerged to run across their beds squeaking as they did so. She switched on the torch only to see the walls covered with strange, pale, crawling cockroach creatures. Max advised her to go to sleep, trying to reassure her with, ‘Once you are asleep, none of these things will worry you’. Finally, falling into a troubled sleep only to be wakened by little feet running over her face, she flashed on the light. Not only had the cockroaches increased, a large spider was also descending upon her from the ceiling. At 2 am she became quite hysterical and threatened to leave for England as soon as the sun rose. Max quickly took command and arranged for their beds to be moved to the courtyard where the star-studded sky and cool air were of great relief.

The following morning Hamoudi their Foreman brought a professional mouse catcher cat to the house. The cat intently searching for any mice emerging from their hiding speedily despatched them all to Agatha’s eternal gratitude.

Apparently, Agatha wrote fast and she estimated it did not take her much longer than six weeks to complete a mystery novel. She typed all her manuscripts using three rather than the more usual two fingers although she started using a dictaphone presented by Collins her publisher on her eightieth birthday, when she found typing tiring.

The question, what makes Agatha Christie’s books and in particular her murder mysteries so popular, is often asked. The key to her novels was the well-made plot. G. C. Ramsey said she must have had the crime worked out in both directions – from the inception to the execution, as carried out by the murderer and from the discovery back to what must have been the planning stages, as worked out by the detective. Once she had completed this, she would scatter real and worthless clues making sure both seemed equally important and that the characters were all in the right place at the right time.

The inability of people to think rationally was one of the key elements in her crime novels. Often, she would have Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple comment that if only people would learn to think properly, applying keen observation, a deep understanding of human nature and logic then they too would be able to solve complex murder mysteries.

Agatha Christie has been accused of over-using the least-likely-person motif. But she also enjoyed using the most-likely-person motif, sometimes having the cunning murderer arrange a whole lot of false evidence to be discovered against him, having made sure there was an alibi available to be released at the most dramatic moment to clear himself, on the crafty assumption that having been cleared once, he would thereafter remain above suspicion.

Another of her arrangements was to gather several people in a particular place prior to one of them being murdered. In this way she created a closed society which made it easier to control the story and which maintained reader interest in all the characters, since any of them could potentially turn out to be the murderer.

For many years she averaged an output of two books per year. This enabled her to keep two novels back, that were supposed to appear only after her death. In the case of Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, the success of the film Murder on the Orient Express convinced her to have it published in 1975. Her murder mysteries, on which her fame rests, totalled sixty-six publications.

Book Cover

Critics generally consider her earlier novels to be superior to those published from the 1950’s onwards. Not that one would have thought so considering the gradual but consistent increase of her first printing figures. By 1950, when her fiftieth book, A Murder is Announced was published, the first printing run came to 50 000 and her subsequent murder mystery books never dropped below this figure. Sleeping Murder, the last Christie thriller and the final Miss Marple story, had a first printing run of 60 000. It is estimated her books have sold in excess of two billion copies and interest in them shows no sign of abating. Even in countries that previously showed slight interest interest in her books such as India, there are now many admirers of her genre.

Let’s now conclude this account with a brief look at Agatha’s beautiful Georgian summer home Greenway, on the River Dart near Galpton, Devon.

‘Greenway’, Summer House of Agatha on the River Dart (Wiki Commons)

In the summer of 1938 Agatha and Max noticed a house on the River Dart was for sale. She recalled the house from her youth and that her mother had always said, was the most perfect of the various properties on this river.

Going over to Greenway, they saw a very beautiful white Georgian house dating from about 1780 or 90 with 33 acres of ground sweeping to the river below. Driving home she mentioned to Max that the price of £6 000 seemed incredibly cheap. ‘Why don’t you buy it?’ asked Max. Taken by surprise she thought why not?

The area around her current house Ashfield had become rather built up and their view of the sea was now obstructed by a large secondary school with noisy children. Their young architect friend Guilford Bell offered to look over Greenway and proposed they pull down the Victorian back wing. This he said, would make the house far lighter and restore its original Georgian appearance. So that’s exactly what they did.

Greenway was never Agatha’s primary residence but the family’s holiday retreat. Here she spent her summers, and where the family gathered for Christmas and Easter.

After the deaths of Agatha and Max, her daughter Rosalind and husband Anthony Hicks lived there. Agatha’s grandson Michael Prichard was determined that upon their deaths, the house that Agatha loved should be made available to the public.

Today Greenway is restored and furnished as Agatha and Max would have known it in the 1950’s. Although the gardens have been accessible to the public for some years now, the house itself has only recently been opened to the public under the auspices of the National Trust.

In the library appears a frieze painted in 1944 when the house was requisitioned by the US Coastguards as part of the preparations for D-Day. Agatha liked it and so decided to retain it. There are three delightful cottages on this property which may be rented by holiday makers.

The library with frieze painted by Lt. Marshall Lee of the US Coastguards (Wiki Commons)

Agatha Christie was buried on 16 January 1976, in St Mary’s churchyard in the little village of Cholsey, Oxfordshire, on a site she had chosen herself ten years before, where she was joined by Max Mallowan when he died on 19 August 1978.

The initials A and M combine to form an attractive ligature on their tombstone (Wiki Commons)

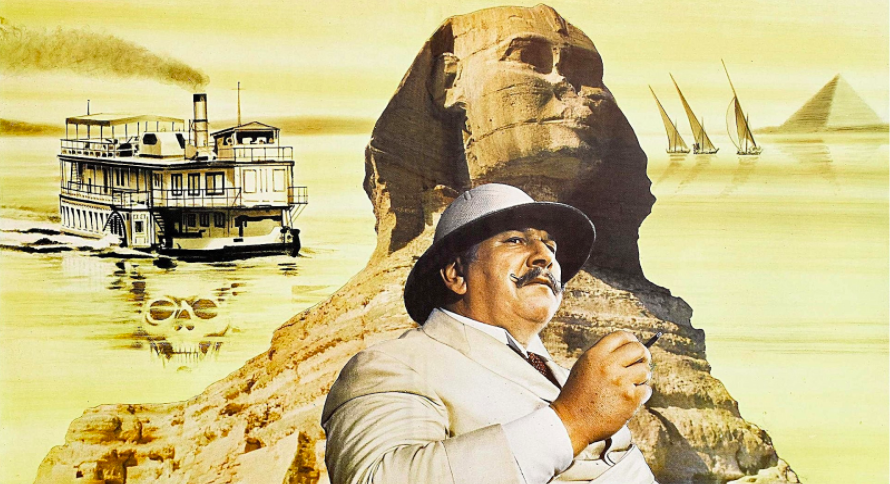

Main image: Death on the Nile poster featuring Peter Ustinov as Hercule Poirot (Wiki Commons)

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Christie A. Agatha Christie – An Autobiography. Collins, London. 1977.

- Christie Mallowan A. Come Tell Me How You Live. Collins, London. 1946.

- Keating H. R. F. Agatha Christie First Lady of Crime. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London. 2020.

- Mallowan M. Mallowan’s Memoirs - Agatha and the Archaeologist. HarperCollins, Glasgow. 2001.

- Osborne C. The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie. Michael O’ Mara Books, London. 1982.

- Ramsey G. C. Agatha Christie - Mistress of Mystery. Collins, London. 1968.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.