Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

'Meccano' was the brainchild of Frank Hornby (1863-1936) who developed and patented in 1901, a metal model construction kit for boys called “Mechanics Made Easy”, which was the precursor of “Meccano”. The name change came about in 1908, and is thought to have emanated from the expression “Make and know” as pronounced with a Scouse accent, as Hornby was a Liverpudlian and got his brainwave by watching the cranes loading ships at Liverpool Docks. In Victorian and Edwardian times it was common for a father to make wooden toys for his children, however, Hornby would cut strips and plates from off-cuts of sheet metal to make toys for his two sons - Roland and Douglas. His hobby would in time become a business and make him a millionaire.

Frank Hornby (Wikipedia)

In the first decade of the 20th century Meccano Outfits (box sets) began selling in volume to budding young mechanics throughout the British Empire and Europe and by the time of the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Meccano Ltd. would relocate to larger premises to meet the demand. The new factory was situated in Binns Road, Wavertree, Liverpool which became the company headquarters for the next 60 years. During the interwar years (1919-1939) Meccano Ltd. would diversify into other lines of toys. In 1920 they would introduce “Hornby O gauge” (1:43 scale) tin plate model trains and in 1934 they would introduce die-cast miniature model cars and lorries under the trade mark of “Dinky Toys”.

When Frank Hornby died in 1936, at the age of 73, his son Roland took over the reins and in 1938 he launched a new range of electric model trains, which were half the size of Hornby O gauge; the famous “Hornby-Dublo” OO gauge (1:76 scale), now considered highly collectable. It was the same year as the Munich Agreement and Neville Chamberlain’s pledge of “Peace in Our Time” but a year later the world would be at war - World War II (1939-1945) and for the duration of hostilities toy manufacture ceased and factory output was switched to making bomb release mechanisms for the fight against the Axis powers.

Meccano would start toy manufacturing again post war as part of Britain’s export drive to rebuild its shattered economy in order to earn valuable foreign currency. The war may have ended but living standards did not improve much for many years to come and an era of austerity prevailed for most of the British population. Austerity lasted from 8th May 1945 (VE Day) until 4th July 1954 (De-rationing Day), when food rationing finally ended after a period of 14 years (it had been first introduced in January 1940). Meat was the last item to “come off the ration” and ration books were thereafter abolished. Childhood obesity was virtually unknown when I was growing up in North West London and any kid who was slightly tubby was called “Fatso” and made to play “Goalie” in a game of football. Television was a luxury that most could not afford and there was only one BBC channel to watch in Black and White; children’s hour was between 5pm and 6pm and then there was an interlude before programming resumed from 7pm until 11pm (for the grown ups). Most of the time the Test Card was displayed on the screen (no bigger than 12 inches) and therefore most people contented themselves with listening to the wireless (radio).

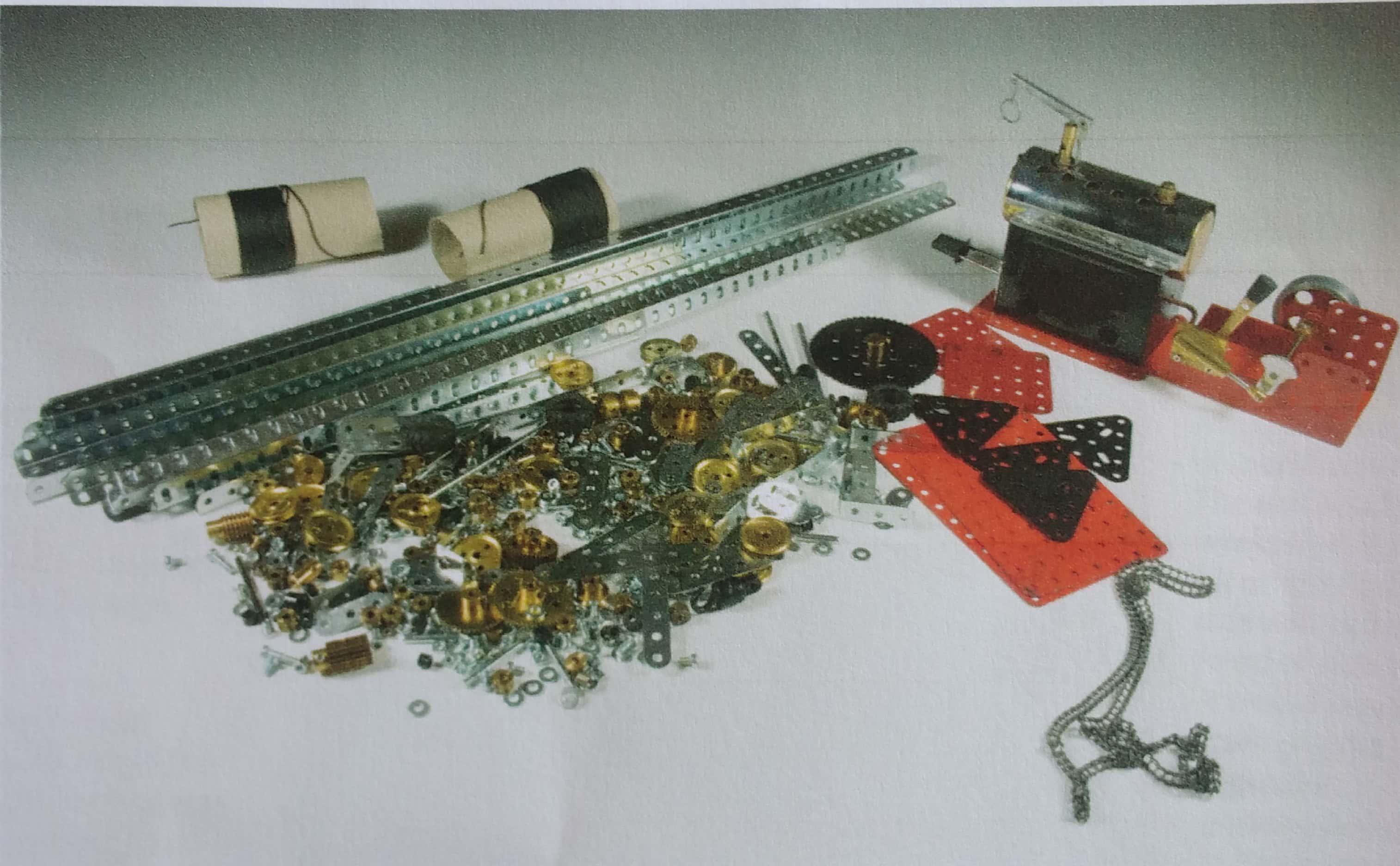

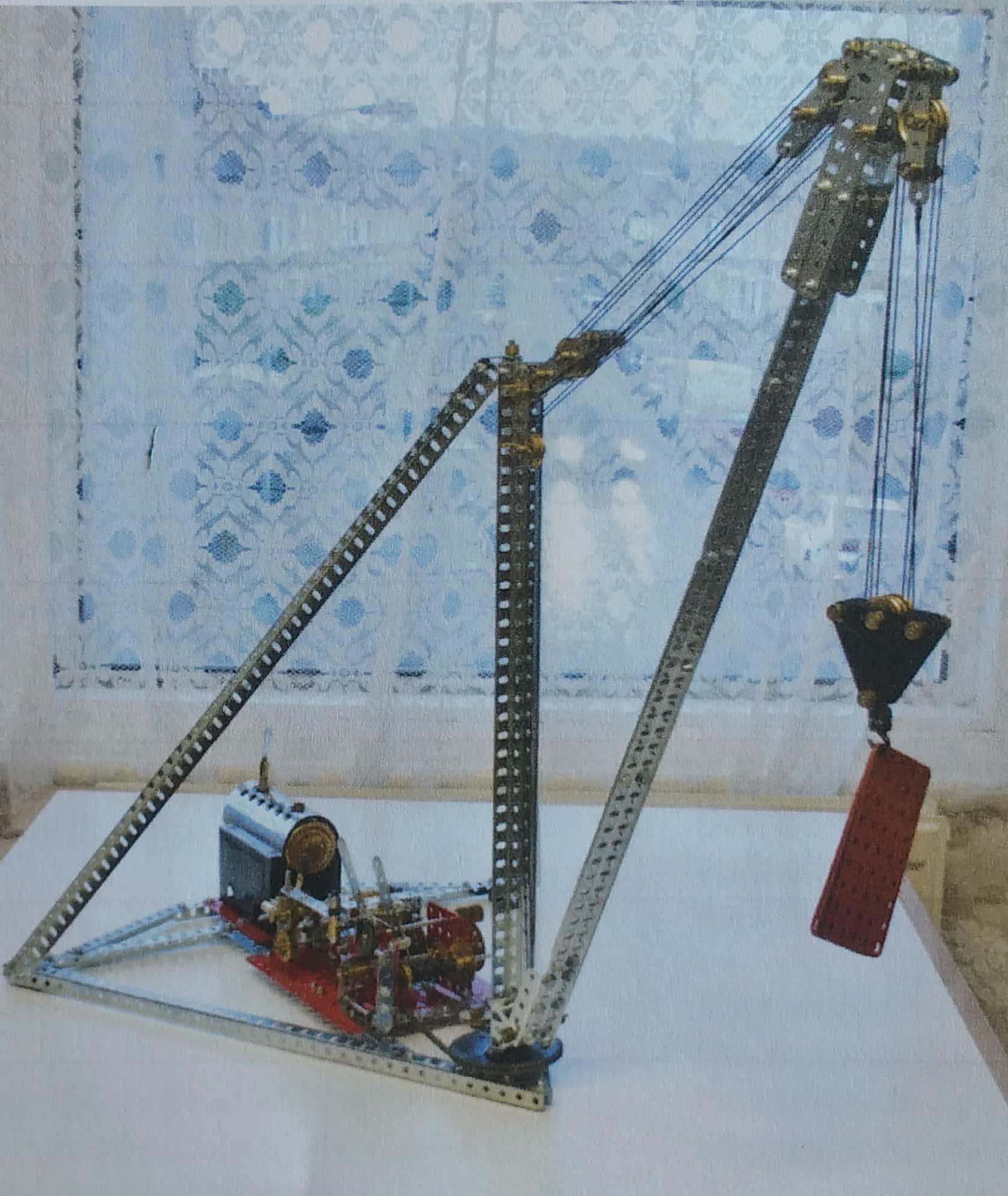

Thus during the 1950’s there was very little to distract a young boy and what was there to do when it seemed to be raining all the time and you could not go out to play? Meccano of course. Outfits (box sets) started at No.1 and went up to No.10 (very expensive) and as my parents could never afford any more than a No.1 set, it meant I could never build the large jibbed crane which was illustrated on the front page of the instructions brochure. On rare visits to Hamleys in Regent Street my brother and I would stand in awe at the Meccano Stand (was it on the third floor?) and watch in wonder the motions of the motorised models until our parents would drag us away with a promise of tea and cake at the Lyons Corner House. A day out “Up West” was always exciting as there was a train journey by the Bakerloo Line (brown on the tube map) to Piccadilly Circus. On coming up to the surface it was a short walk to Hamleys, which would be the first stop on a day out in the West End which would include the Science Museum and end by a walk through Hyde Park before taking (and falling asleep in) a train home.

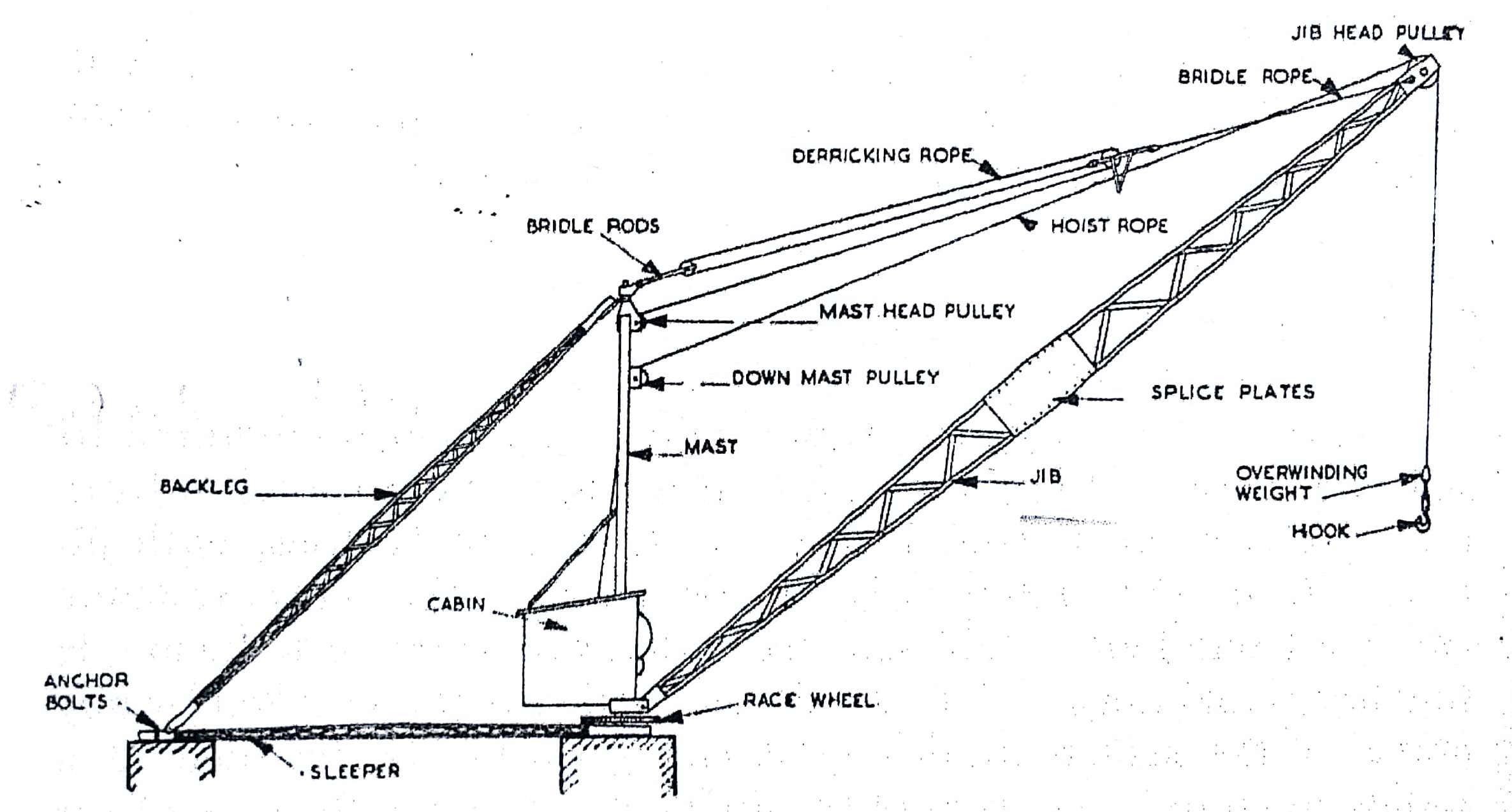

Diagram of a Scotch Derrick (Steel Erection BCSA)

Let the assembly begin (North East London Meccano Club)

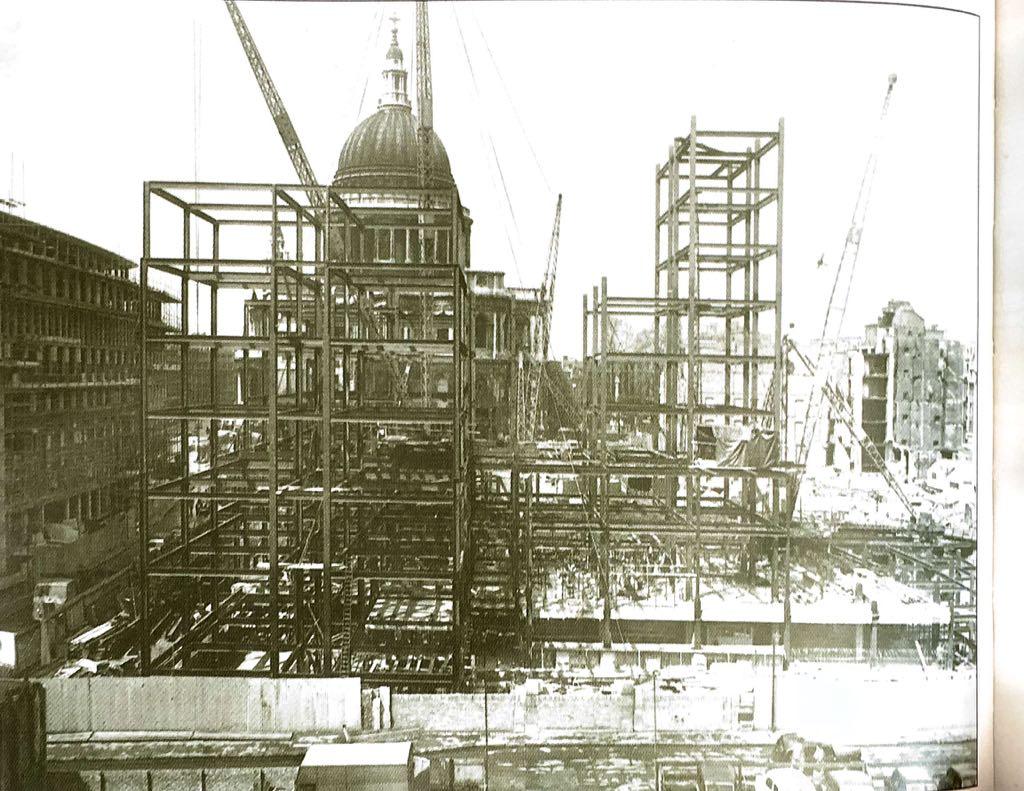

Whilst walking, a common sight was to see a new building going up where an old one had been bombed out during the Blitz. The cranes that were lifting the steel girders and other building materials were not the tower cranes that we see today on the Sandton skyline but the Scotch (stiff leg) Derrick which would luff and swivel. I was captivated by them and wanted to make one of my own, but had I enough Meccano to do the job? Well my father had some back numbers of the Meccano Magazine from his boyhood and I was lucky enough to find an article on making a “Stiff-Leg Derrick”, I was in business. The Derrick described therein was a miniature version of the real thing, built the same way you would the prototype, with the capability to not only raise or lower the jib but also to swing around (on plan) through 180 degrees. Unfortunately I did not have a sufficient number of parts to complete the model but nevertheless I made a start with the belief “that a job begun was half done” and that I could source the parts I needed over time. I was then ten years old and sad to say I never was able to finish the model, but the failed attempt sowed the seed to work in civil engineering.

New building going up after the war

Famous shot of a London bus thrown into a building during the Blitz (London Transport Carried On)

On leaving school, at 16, I became an office junior (on £3-15s-0d a week) for a partnership of Structural Engineers, my job was making prints of drawings, folding the prints for issue and running errands with the promise to be trained as draughtsman, when the next new intake of juniors would arrive the following year. Half a century ago to become a trainee draughtsman was the first step on the ladder to becoming an engineer and that end was dependent on one’s ambition and technical aptitude. These days to be a Professional Engineer (Pr Eng) you need a BSc degree and draughtsmanship is no longer a prerequisite.

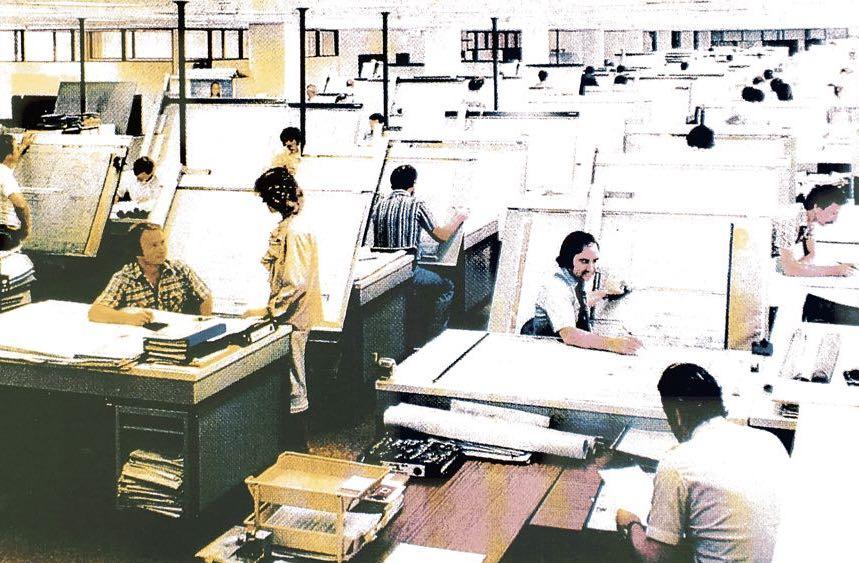

Drawing office before computers

Post war and up until the late 1960’s, many aspiring young men (from 16 to 22) attended “Tech”, either by doing evening classes or going one day a week (day release), where they would learn the technical “gen” needed, whilst working for an engineering company, whether they were in a workshop, on a building site or in a drawing office. The “Holy Grail” was to get a Higher National Certificate (HNC), which was a respected qualification throughout the English speaking world and the minimum entry qualification to an engineering institution (that is until 1969).

South African Companies took advantage of this large pool of well trained engineering personnel and regularly placed adverts in the British press for engineers, designers and draughtsmen. I answered the call and after ten years of working for Consulting Engineers in London and still single I decided to see the world and came to Johannesburg on a two year contract with Murray and Roberts (and I am still here).

After six months of living in South Africa I received a letter from my mother saying that the large tea chest, they had been storing, which contained my Dinky Toys, Hornby-Dublo and Meccano had been given away to the 10 year old son of a cousin, did I mind? I knew then I was destined never to finish the Scotch Derrick.

Completed Scotch Derrick (North East London Meccano Club)

I wonder how many other Engineers owe Meccano a debt of gratitude for making them pursue a career in engineering and do they have a similar tale to tell?

References and further Reading / Viewing

- “What is Meccano? the Magic of Meccano – a hobby for young and old” by Patrick O’Shea, www.mecworld.co.za

- Meccano has always been seen as an educational toy and from 1916 to 1981 the Meccano Magazine (archived on: www.pdfmm.free.fr) was published with many articles on engineering topics to provide the young reader with knowledge of the world around him.

- “Factory of Dreams – A History of Meccano Ltd.” by Kenneth D. Brown, published by Lancaster: Crucible, 2007.

- “Why Britain needs more Meccano and less Lego”, a Daily Telegraph newspaper article.

- James May’s Toy Stories – building a bridge made of Meccano over a canal in Liverpool (can be seen on Youtube).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.