Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Photographs produced on thin iron sheets? Yes, indeed! And it was cheap, even cheaper than the equivalent middle-class, paper based Carte de Visite. Photos on these thin iron sheets were actually referred to as a ‘plebian photographic end result’.

From their origin in the 1850s until the end of the twentieth century and beyond, these photographs remained popular because they were so inexpensive.

These photographic images were initially called melainotype plates. Today they are either referred to as ferrotypes, or more commonly, tintypes. As the tintype was iron rather than tin, the name tintype is therefore a misnomer.

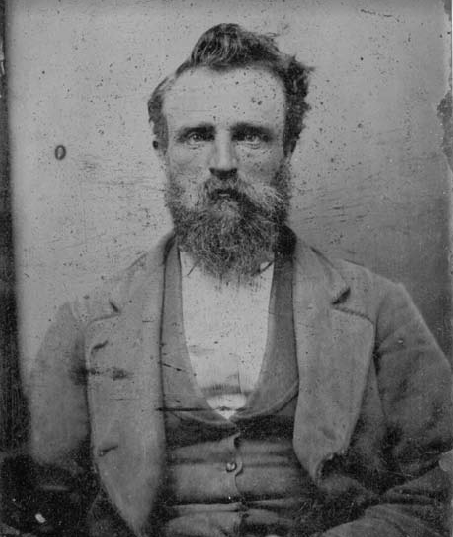

An example of a tintype photograph

Originating in France during 1854, the tintype was first patented in the USA during February 1856 and in England during December of the same year.

In the case of the tintype, the negative was made not of glass but a thin sheet of iron coated with an opaque black or chocolate-brown lacquer or enamel.

The lacquered sheet, which was commercially available, was coated with wet collodion containing silver salts just before exposure in the camera. Development immediately followed exposure. Later refinements led to the use of dry-collodion-coated metal plate.

The tintype was derived from another photographic format, the ambrotype. Like the ambrotype the tintype depended on the fact that a collodion negative appeared to be a positive image when viewed against a dark background. As the finished image was in fact, although not in appearance, a negative, the image was usually laterally reversed.

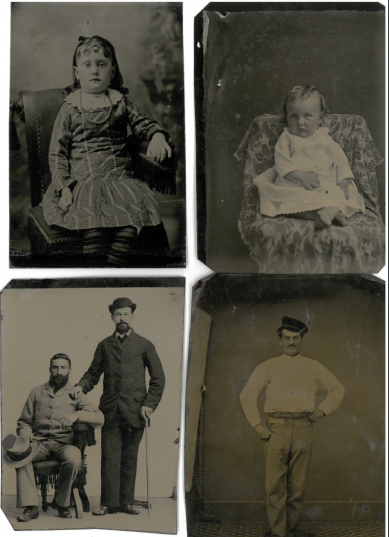

A selection of tintype photograhs

The tintype was more durable than any other photographic end result available at that time. Because the surfaces of tintypes were not fragile, they could be sent through the mail, carried in pockets and mounted in albums. They were cheap, not only because the materials were cheap, but also because by using a multilens camera, several images could be secured with one operation. After processing, the plate was cut into single pictures with shears.

A tintype was unique and could only be duplicated by being re-photographed. Despite the image reversal, tintypes were almost always used for portraiture. Portraits in the tintype format were therefore common while scenic views in this format were rare.

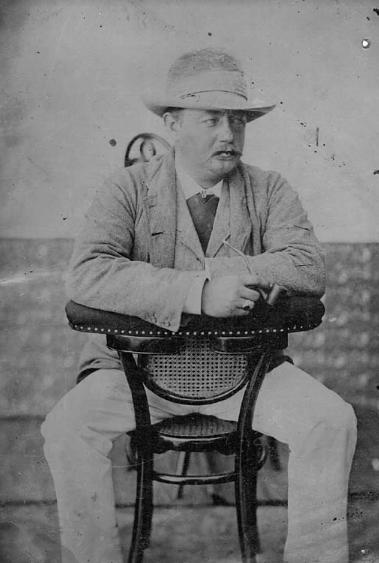

Larger format tintype of a seemingly sophisticated gentleman

Tintypes were enormously popular, yet, due to the fact that very few photographic artists added their name to the final photographic result, (like they did on Carte de Visite or Cabinet Cards) it was difficult to determine which professional South African photographic artists produced tintypes; or even, which tintype photographs were produced in South Africa. Although there have certainly been many South African based photographers producing tintypes, the author has yet to positively link such photographs to South African photographic artists.

The reason for this could be that most photographs in the tintype format were produced by the less professional photographer. Tintypes were often made by street vendors. Requiring the least skill of all comparable processes, it became popular with those producing cheap photographs and with the growing band of itinerant (traveling) photographers.

Instant photographs are not new. They originate from these very same street or traveling photographers. By the end of the nineteenth century and through the early years of the twentieth century few fairgrounds, market places or seaside resorts were without their instant American tintype photographers. They were processed while the customer waited. The finished product, still moist, was handed to the client there and then.

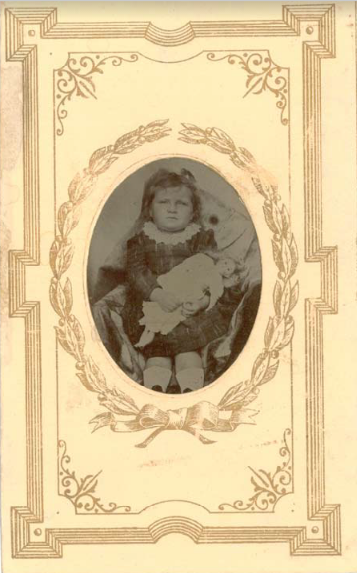

Tintype material could be cut to any shape or size and was also inserted into brooches, rings, lockets and other small items. Tintypes were typically inserted into simple folding cards or window mats, sometimes also made of thin metal. Artistic paper window mats were more common. In many instances the art on these frames was more appealing than the photograph itself. Sadly these paper frames got damaged long before the actual photograph. To find a photograph mounted on an undamaged frame is therefore quite unique.

Tintype mounted on an artistic window mat

Although the images are of poor quality in most instances, photographically speaking, many are especially interesting in the social sense in that they record the appearance, customs, dress, and leisure activities of those who could not afford the better forms of photographic imagery.

When tintypes were first introduced, ordinary wet plate cameras were used to take them, but soon special weird and wonderful cameras were made to take these photographs.

Backdrops and props for these types of photographs were typically crudely artificial. Paint was also used on occasions to give the face some color or to touch-up a bouquet or a necktie.

In many instances tintypes are simply pasted onto the back of a window mat. Over time the images have become detached from their original mounting, resulting in only a small photograph on a piece of iron. Potentially vital information that might have been recorded on the front or the back of the window mat might have got lost in the process.

These poor man’s photographs certainly have their own nostalgic charm, yet few people are aware of the fact that some of the pre-1900 photographs in their possession are actually based on a thin sheet of iron and not on glass or paper.

Another example of a tintype mounted on an artistic window mat

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.