Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Visiting Westcliff is always a treat. I feel like a Johannesburg time traveller when driving north along Jan Smuts Avenue and turning left at The Valley Road. In October and November it is a riot of purple when the jacaranda trees and the creeping bougainvillea blossom. E. M. Macphail, who wrote the charming book The Story of Westcliff in 1986, makes it her quest to find the right descriptive words for Westcliff. She comes up with “rich, elite, chic, wealthy, posh, privileged, stuffy, spacious, green seclusion”.

Westcliff is still regarded as a luxury suburb of choice for the affluent families of Johannesburg. It is a suburb of mansions, large stands, wide roads, secluded greenery, beautiful gardens, imposing gates, aged trees and high walls. Westcliff is one of the most beautiful suburbs of the City. It is a jewel of a garden suburb on a prime Witwatersrand ridge and has a unique charm.

Ye Rokkes, an iconic Westcliff mansion designed by the firm Aburrow and Treeby in 1902.

There are many Baker houses in Westcliff. Baker and his partners brought Kent and the spirit of the English home counties to the ridges of the burgeoning town but built with the honey-hewed kopje rocks found on site.

The home Black Roof was designed by the architects Baker and Fleming in 1910 (Kathy Munro)

Johannesburg was not yet a city – and did not achieve city status until 1928. Timber was often imported and roofs were often made of shingles. Dormer windows set off in the roof helped bring the fantasy of a cottage to substantial and gracious homes of substance. Tall chimneys give height and show a functional attention to the winter cold on the Highveld - the chimneys are almost signature features. Baker encouraged quality craftsmanship and stone masons and the local building trade quickly rose to his standards to build these enduring homes with the mix of spacious rooms and a deft handling of materials. The builders of these homes were invariably Barrow Construction. The rock comes in large hewn blocks – each one must weigh at least 250 kilos and required expert stonemason skills to pick the right rock to shape for corner stones or to become a building block in a foundation course.

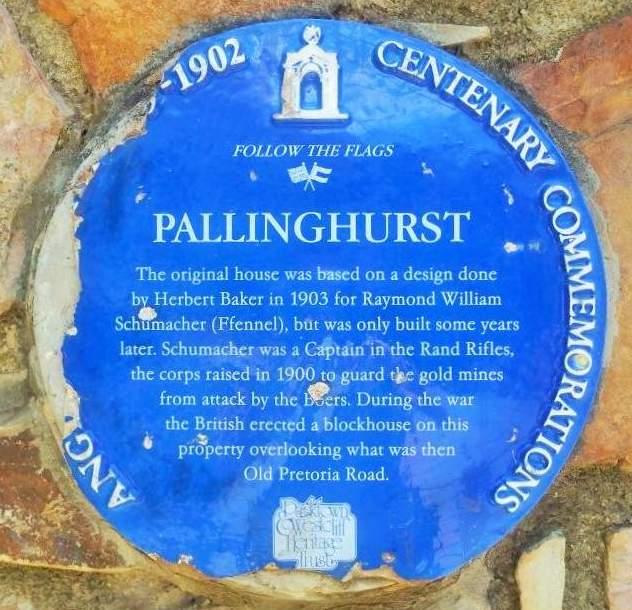

To maintain properties of this size must take an army of people; all of this is serious wealth but it’s a quiet confident opulence that does not need to be on show to the passers-by. Big gates and high stone walls, topped by electric wire strands, set out the boundaries between the public street and the private domain. Many Westcliff homes have blue plaques which cross the boundary because they explain what lies within to the curious man or woman in the street.

One of the Westcliff blue plaques (Kathy Munro)

Over time the architecture of the area became eclectic but it was Herbert Baker, and his partners Ernest Willmott Sloper and later Frank Fleming who first had clients clamouring for arts and crafts style English houses but with nods to the Highveld Witwatersrand ridge location. The local warm honey coloured quartzite rocks found on the ridges of the city became a prime building material.

Westcliff was the suburb developed by the Braamfontein Company from 1902 as the second alternative quality suburb to the neighbouring Parktown. It was also carved out of the Braamfontein farm which was purchased by the Eckstein company anticipating possible gold mining prospects. However, there was no gold beneath the surface as the land lay too far north of the Main Reef. The Braamfontein Company was incorporated in 1892 and Parktown developed as the first garden suburb on Parktown ridge. Parktown was a pre Anglo-Boer War success, a colonial enclave with its very British sounding streets such as Victoria Avenue, and Jubilee Road.

Hohenheim, one of the first mansions on the Parktown Ridge

After the Boer War, with the British colonial administration firmly in charge, a new suburb offered possibilities to extend Parktown. Initially Westcliff was called West Cliffe, a descriptive name because it lay west of Parktown and was on a rocky cliff top. The two word appellation was soon dropped in favour of the easier on the ear, Westcliff.

View towards Westcliff from Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

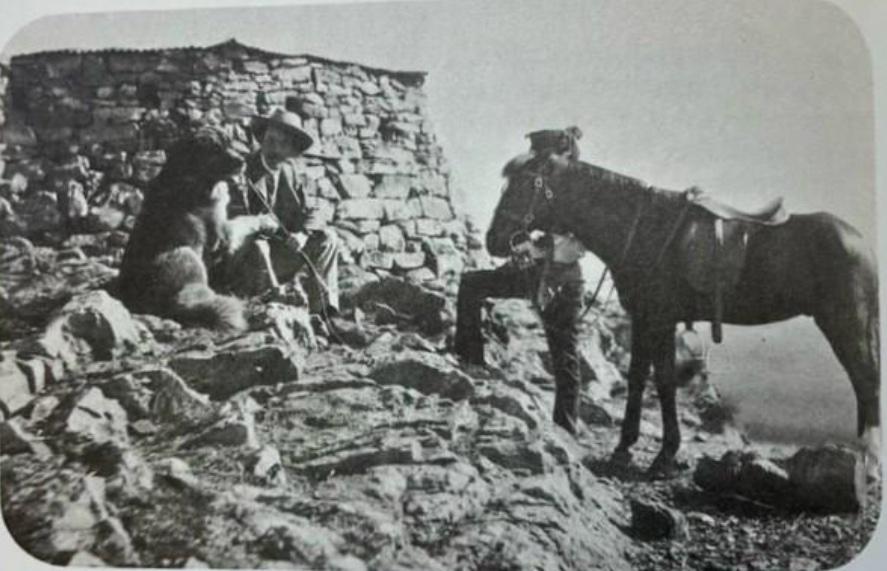

The first purchaser of note on this ridge was Raymond W Schumacher who, as early as 1901 as a new director of Eckstein and Company, offered the Braamfontein Company £3 600 for a large site on the northern end of the steep ridge. The site was more than 26 acres and was the start of the suburb of Westcliff. There is an early photo of Schumacher on the site of his proposed house, with a dog and a horse. An inscription on the reverse side says: “August 1902 - the Block House – site of the future house“. In the background, a Boer War block house is visible, built in this key strategic location in 1900.

Schumacher on the Pallinghurst site

It was an ideal north facing top of the ridge site. His offer was accepted and the land was purchased on a leasehold basis at a ground rental of £5 per month. It was a superb bargain as within years the selling price of a Westcliff acre was set at £400 an acre (Schumacher paid £135 an acre).

In August 1902, Schumacher actually camped on the ridge during construction. He described the projected building as consisting of stables, coach house, kitchen and two rooms. Hope Schumacher, the new young wife of Raymond commented on early life at Pallinghurst:

Our view was quite lovely from the stone block house above, and perhaps at its loveliest framed in the wide-square pillared unglased windows of the verandah room to which the main entrance of the house has direct access. Nearly all the rooms looked out on to this view which extended over the large evergreen plantation 200 feet below, and beyond.

Hope also described the new wing (one can only assume that this was somewhat later):

The new wing came up to our expectation and the new grass terraces were what we had hoped for. By Christmas we were in. Our own three sitting rooms opened off the wide corridor and all faced the great view. The house was spacious and healthy and amusing to live in, and our friends liked it.

The Schumachers lived at Pallinghurst until their return to England in 1915 and took the decision to donate the property for use as a convalescent home. The Hope Convalescent Home was established with the objective of housing and educating disabled students. It was named after Hope Schumacher. In 1929 the Hope School was established by the Department of Education on the Hope Home premises to provide a holistic environment for children with physical disabilities. It became an institution of distinction particularly in addressing the human tragedy of the polio epidemics.

Pallinghurst (The Heritage Portal)

The Pallinghurst Blue Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Between 1903 and 1906, Schumacher, along with other key directorships, was the chairman of the Braamfontein Company and hence his energetic promotion of the Westcliff suburb. He was the father of Westcliff. As mentioned, he chose to build his own grand house, Pallinghurst, here. Pallinghurst was also the name of the principal road in the suburb. The name was derived from his father’s estate in Surrey, England - Pallinghurst Park which was purchased in the late 19th century as the family's country residence.

The Braamfontein Company hoped that purchasers would invest in land to build homes of distinction as an expression of confidence in the future of the mining town. Westcliff was surveyed and laid out in 1902. The stands, or plots as they were called, did not conform to a grid pattern, which was the norm in other Johannesburg suburbs of the time, but followed the natural contours of the ridge. This gave the suburb a 'garden suburb' ambience from the start.

The suburb extended over 147 morgen 367 square roods. An early map shows 67 plots and four 'reserves' where ownership was retained by the company. These were later developed into building stands. The roads of Westcliff are 50 feet wide with space for pavements, grassy verges and cultivated sidewalk flower beds.

Initially Westcliff lay outside the Johannesburg boundaries but in December 1903 it was incorporated into the now expanding boundaries of the town as expansion rushed ahead in widening concentric circles. A regular water supply was a challenge – piped water was a luxury and like Parktown, Westcliff relied on supplies from San Souci.

The first purchasers were men who had the funds to purchase multiple acres – they were mining engineers, doctors, lawyers, and members of the church and the military. The best and largest homes were on the generous sized stands of a few acres or more and commanded those stunning panoramic views north to the Magaliesberg. The eastern side of the suburb overlooked the old Pretoria Road. It was a main arterial road north and in 1917 was renamed for Jan Smuts in honour of his first world war leadership.

John Jolly bought 4 acres in 1902. William Dalrymple purchased his estate of 18 acres close to Pallinghurst (later this had shrunk to 6 acres). Five acres went to Dundas Simpson and Woolls-Sampson purchased 6 acres. Woolston Road was named for Sir Aubrey Woolls-Sampson, a man with a military background who had fought in the First Anglo-Boer War and established the Imperial Light Horse in the Second Anglo-Boer War. He was a member of the uitlanders Reform committee of 1895. His home was the Woolsack on Woolston Road which became The Ridge School in 1919.

The Ridge School (The Heritage Portal)

Between 1902 and 1918 only 49 stands were sold and fewer than 40 houses were built. Pallinghurst, Glenshiel, Ye Rokkes, Black Roof and the Woolsack were among the great houses. These were the first houses of character, size, aspiration and grandeur. The owners sought to live up to the title of Randlords.

Despite the best efforts of Schumacher, a generous and supportive approach towards early schools, public spaces and backing for a tram line down the old Pretoria Road, Westcliff was not instantly popular. The price of £400 an acre was well above the price of stands in Parkview, Parkwood or Forest Town and Parktown was still considered closer to the city and with more élan. A reliable water supply was still an issue and boreholes had to be sunk. Pallinghurst and Glenshiel dominated the northern side of the suburb.

Horses and dogs were an integral part of the lifestyle where the seigneur, perhaps in the early morning or as the sun set to the west, would ride out to his boundaries on this high ridge accompanied by his pack of dogs.

The economy of the Edwardian household was self-contained and grand – grooms, gardeners, butlers, housekeepers, parlour maids and cooks, nursery staff for the children. Often the staff were immigrants – for example Scottish house maids or an English nurse who also had to be a good needlewoman or a German cook. African staff were also employed for more unskilled menial hard labour to tame the wild overgrowth on the hillside and make those magnificent gardens. Accommodation for less skilled staff was often very basic.

The street names of Westcliff are topographical (Waterfall, The Valley Road) or take the names of African rivers (Usutu and Palala) or are named for early distinguished people (Lawley and Woolston). The origin of Pallinghurst has been explained above. Lawley was named in honour the Lieutenant Governor of the Transvaal from 1902 to 1906, Sir Arthur Lawley. Dalrymple Road lies below Glenshiel, the home of Sir William Dalrymple who commissioned Herbert Baker to design his house.

Old postcard of Glenshiel

The suburb came into its own after the First World War. Between 1919 and 1927 at least 100 stands were sold. The Braamfontein Company was absorbed by the Transvaal Land and Exploration Company and this latter company was more energetic in their marketing. New names appeared in Westcliff: Cook, Welch, Hathorn, Sessel, Kent, Spencer. Ernest Oppenheimer purchased ground, presumably for later development, but today it is the cricket field of the Ridge School. In 1921 sewers were installed and sanitary lanes were closed.

Murray Gordon Mansions, erected in 1918/1919, was the first luxury block of flats in Johannesburg. It is a building that no longer exists and was mourned by Arnold Benjamin in his book on Lost Johannesburg. The architects were Waterson and Veale. Here was another example of Herbert Baker’s influence in Westcliff with a series of peculiar chimneys that came off Cape Dutch style gables. Each flat had its own fireplace. It comprised 27 flats on just under 4 acres of ground. It was originally named Westcliff Park. The developer was a Samual Sondheim and his wife was the registered owner, a Mrs I Sondheim. They lived at 32 The Valley Road. Sondheim was a tree enthusiast and planted many trees on the site. A later owner was the attorney Nat Gordon who named the flats after his son Murray.

The presence of this apartment block in Westcliff was controversial from the start. It was said that permission to build had been granted by the authorities in a fit of absent mindedness but when it was demolished in 1975, its passing was protested and mourned as a piece of Westcliff 'heritage'. Clive Chipkin described the building as 'an Arcadian vision of hill-slope architecture half visible amongst large trees'. It was a block that could have been in London, but it was a Johannesburg site at its best with a tennis court, croquet lawn and a children’s playground. It was a loved building - a contemporary called it 'elegant bohemia'.

After the Second World War, a succession of new owners purchased the site with an eye on redevelopment. Transformation into the Westcliff Hotel took years through many troughs and peaks of the property cycle, several owners and a vigorous and expensive opposition of the residents and owners of Parktown, Forest Town and Westcliff. Today, The Westcliff is an exclusive five star hotel.

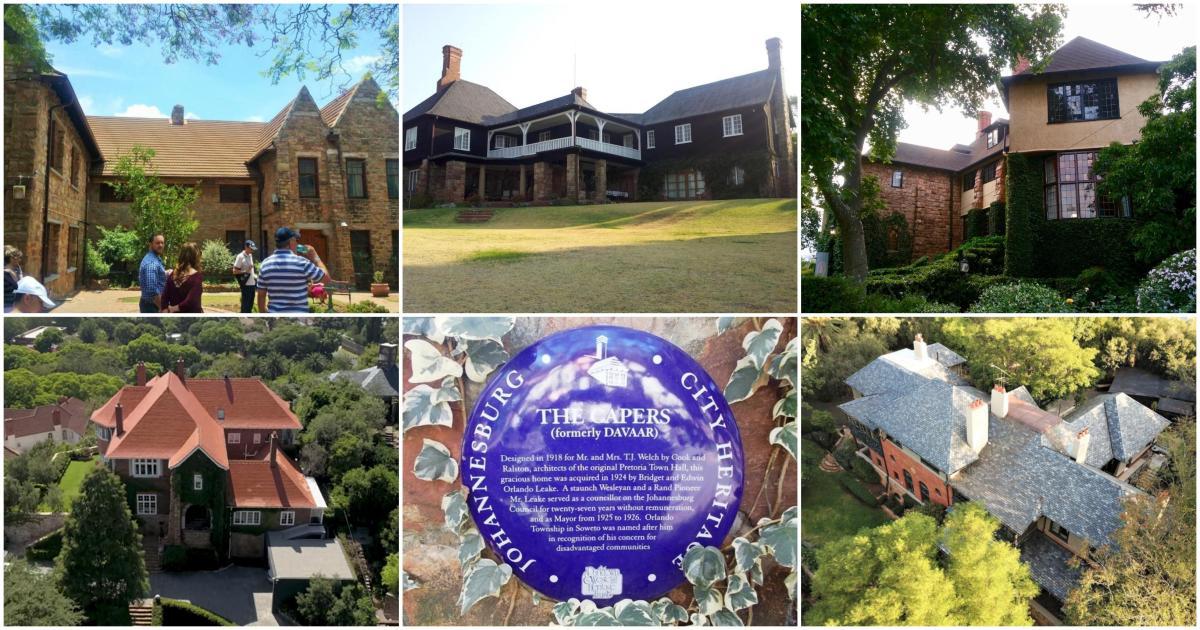

Four Seasons Hotel (Trip Advisor)

It was only after 1935 that property development picked up and a much more varied and mixed range of new owners bought into Westcliff. The first generation of owners had moved on or passed away and their houses were sold. New houses were built. Victor Kent, for example, built a new home at 11 Woolston – Windyridge (Kent was the foresighted man who guided the purchase of land in Illovo for the Wanderers Club – Kent was the chairman for 30 years). George Haggie purchased Glenshiel in 1943 and for the duration of the Second World War it became an auxiliary military hospital. Westcliff Extension was developed from 1927 with smaller, less expensive stands. The writer and poet C M van den Heeveer came to live in Palala Road in 1934. Orlando Leake lived at 5 Wexford Road. He was a City Councillor and Orlando in Soweto was named in his honour. Many doctors came to live in Wexford Road.

The Capers, 5 Wexford Road (Byron Thomas)

The Princess Alice Adoption Home was established in 1930 in Westcliff and was named for Princess Alice, the Countess of Athlone, whose husband, the Earl of Athlone, was the Governor General between 1924 and 1930. A house was built in the grounds of the Hope Home funded by the estate of Dr Kerr Muir.

Through the decades, Westcliff evolved in response to new owners, new styles, new architects and somehow the architecture blended. There are Baker homes and Arts and Crafts homes but there are also Modern Movement houses and Post Modern houses.

Westcliff is a suburb that needs to be explored on foot - in this way one takes in the details of fine handcrafted aged wooden gates, stone hewn pillars, quartzile stone walls, pavement gardens. There are trees of age, substance and beauty. Some are indigenous but many are foreign such as jacarandas, oaks, cork, pepper, plane trees and eucalyptus.

Looking out over the jacarandas from the Westcliff Ridge (The Heritage Portal)

Today, Westcliff homes are keenly sought after. It is still a secluded suburb. It has survived better than Parktown which has been largely lost to highways, business parks and educational institutions. Westcliff retains the atmosphere of old Johannesburg where the 'nouveau riche' of 1902 have evolved into 'old money' but those with aspirations and a bank account to match are welcomed. Old and new styles of architecture blend. Westcliff boasts many fine homes and blue plaques are no longer rarities. Sometimes a house is lost – a tragedy that hit Duntreath in Pallinghurst Road in 2020.

Fire engulfing Duntreath (Kathy Munro)

Old photo of Duntreath (Alan Yates Collection)

The suburb has a strong sense of community with an active residents association. These are the property owners who strive to protect and promote the suburb with its special residential character. As a group they are keen to raise awareness about the history and architecture of Westcliff. This group has been keen supporters of the blue plaque movement and it has been my pleasure to work with them in identifying more properties for this accolade.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.

References

- Nini Bairnsfather Clote and Craig Fraser: Remarkable Heritage Houses of South Africa. 2016

- Doreen Greig. Herbert Baker in South Africa. Purnell. 1970

- Michael Keath. Herbert Baker Architecture and Idealism 1892-1913. The South African Years. Ashanti. 1992

- Arnold Benjamin. Lost Johannesburg. Macmillan. 1979

- Anna Smith. Johannesburg Street Names. Juta. 1972

- E M Macphail. The Story of Westcliff. Palala Press. 1986

- A P Cartwright. The Corner House. The Early History of Johannesburg. Purnell. 1965

- A P Cartwright. Golden Age - The Story of industrialization of South Africa and the part played in it by the Corner House group of company 1910-1967. Purnell & Son. 1968

- Clive Chipkin. Johannesburg Style Architecture and Society 1880s – 1960s. David Philip, 1993

- Clive Chipkin. Johannesburg Transition. Architecture and Society from 1950. STE publishers. 2009

- Barlow Rand Archives. Archive now at the University of the Witwatersrand

- Daphne Saul and Flo Bird. The Braamfontein Company: Developing Parktown. No 25 of the Parktown Collection published by the Parktown & Westcliff Heritage Trust

- John Wentzel. Raymond Schumacher. No 6 of the Parktown Collection published by the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust

- Holmden’s Register of the Townships Maps of Johannesburg and District no date, circa 1923 to 1950

- Dictionary of South African Biography vol 3. Entry on Raymond Schumacher.

- The South African Who’s Who 1908. South African who’s Who publishing Company, Durban

- Websites for Hope Home and the Princes Alice Adoption Home and the Ridge School

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.