Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

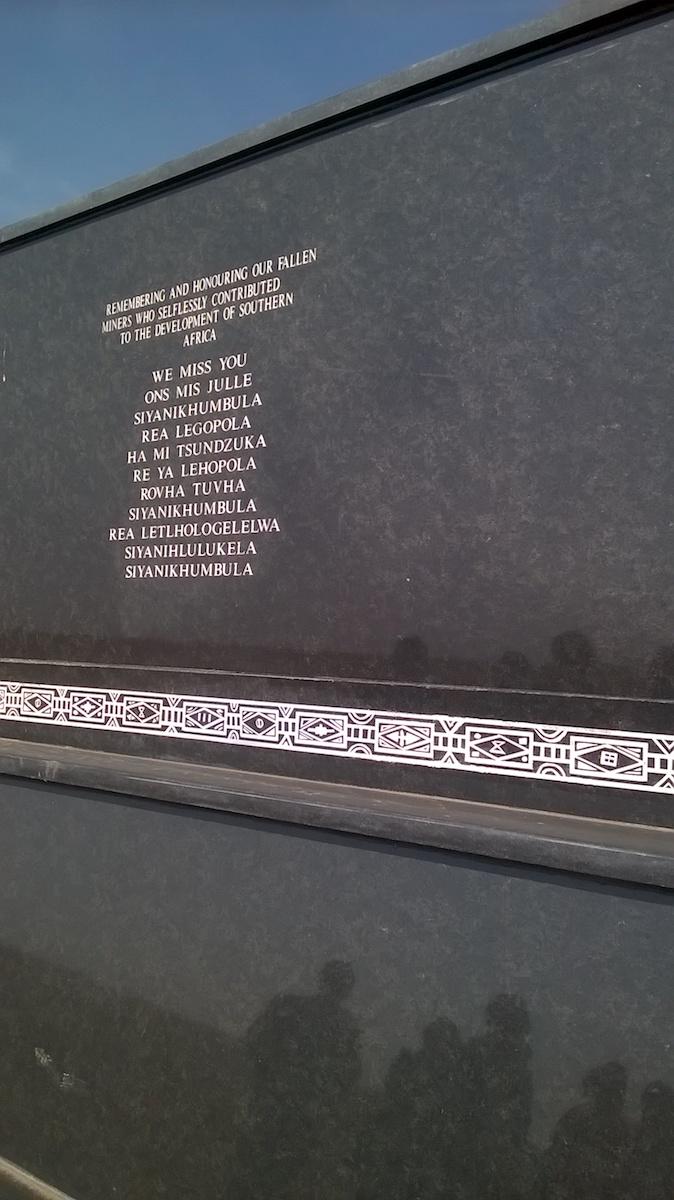

On 13 August 2018, Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources revisited the Winkelhaak Cemetery at Evander Gold Mine, Mpumalanga. The Committee noted progress in improving the infrastructure at the grave site by the Winkelhaak Cemetery Project. Since their last visit in 2015, a wall has been built around the whole site and a granite monument has been erected.

Memorial stone at the gate to the cemetery (Martin Nicol)

The Committee asked if it is possible to determine which mining company was responsible for these burials and who were the directors who ran a company with this policy? Swift research concludes that Winkelhaak Mines Limited was responsible for the burials. This was a company under the mining house Union Corporation Limited which merged into Gencor in 1980. None of the companies exist under these names any longer. Archival research would be needed to determine the identity of all the company directors responsible. Because of the passage of time, it is likely that most directors will be dead.

Union Corporation Head Office Building (The Heritage Portal)

Old watercolour of the Union Corporation Building

Given the lack of records to specify the dates of burials, it would, in any event, be difficult to link directors to burials that occurred over a period as long as 30 years. The three top leaders of Union Corporation during the period of the burials were:

- T. P. “Tommy” Stratten – MD and then Chair of Union Corporation 1954 to 1972.

- C.B. (Colin) Anderson – MD and then Chair of Union Corporation 1965 to 1974.

- E. “Ted” Pavitt – MD and Executive Chair of Union Corporation, then CEO of Gencor 1972 to 1988.

The last of these leaders, Ted Pavitt, died in 2007, aged 89.

The first General Manager of Winkelhaak Mines from 1955, R. K. Boright – who laid out a cemetery at Winkelhaak when the mine started – died in 1993.

Gary Maude, the last Gencor director responsible for Winkelhaak before it was sold to Harmony, died in 2012, aged 73.

Entrance to the old BHP Billiton Building (The Heritage Portal)

Stories of the graves

Large and profitable, Winkelhaak was one of South Africa’s most successful gold mines. It was the first mine established by Union Corporation on a new gold field to the east of Johannesburg after the Second Wold War. Winkelhaak, now in Mpumalanga Province, was followed by the nearby mines Kinross, Leslie and Bracken.

Today the mine is owned by Pan African Resources and is known as Evander 7 Shaft. The Evander mine stopped operations and retrenched its 1,700 workers in 2018.

Gencor (renamed as Billiton) sold off its interests in gold in South Africa, so from 1998, these mines were subsidiaries of Harmony Gold Mining Company Ltd.

In about 2006, Winkelhaak, Leslie and Kinross mines amalgamated under a new company name: Evander Gold Mine.

Pan African Resources took over control of Evander in February 2013 and are the current owners of Winkelhaak. They were not involved in the history of the graveyard.

Evander Gold Mine, 2018

With this succession of owners over the last 20 years, documents have been misplaced and institutional memory has been lost. Mr LT Moshwaiwa, General Manager on the Evander Gold Mine briefed visiting members of Parliament on the Winkelhaak Cemetery Project in August 2018:

The Cemetery was established in the late fifties. The last burials were in the late eighties and the total number was almost 1,000, but there were no records linking the numbers on the grave plots to the names of people. Apparently, the burials were predominantly employees from foreign countries (SADC). Mainly they were employees who worked for Union Corporation Mines who died of mine related accidents and natural causes. Families were informed by means of a telegram. If no response was received from the family within 10 days, then the deceased employee would be buried. The changes of company ownership could have possibly contributed to loss of information or records.

Former and current employees who were present during the period of the burials have been interviewed. These included a Hostel Manager, a union branch secretary, a former miner and human resource executives.

TEBA [the mine worker recruitment agency, formerly run by the Chamber of Mines] indicated that they do not have easily-available records on mine employment.

Assigning responsibility

1955 to 1959: Hard to find the directors of Winkelhaak

In 1955, Union Corporation applied for a mining lease for Winkelhaak Mines Limited. Winkelhaak's first gold was poured in 1958. It would be possible, but difficult, to trace the directors of Winkelhaak between 1955 and 1959. There is, however, little point as all would probably now be dead from old age. If a director was a young 40 years old in 1955, he would now be 103.

1960 to 1996: Easy to find the directors of Winkelhaak

From 01 January 1960 to 15 November 1996 Winkelhaak was a listed company on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. For this period, the names and details of the directors of the company were listed in the Annual Reports of the company, which are public documents. Its directors for these years (which cover some of the years in which it is thought that workers were buried in these graves) are traceable – but many will have died by now.

Publicity on the Winkelhaak burial site, 2014

The cemetery at Winkelhaak was brought to public attention in 2014 when David Msiza, the Chief Inspector of Mines, addressed industry leaders at a conference on mine safety and the concept of “zero harm”. To illustrate the need for an entire shift in attitude from practices of the past, Mr Msiza included in his presentation “images of row upon row of anonymous grave sites on the Evander gold mine property.”

Mining Weekly reported: “The pictures of the graves, which number about 1 000, showed a run-down, concentration-camp-like hostel structure in the foreground, where mineworkers were accommodated before being buried in the stark surrounding cemetery. ‘The way they were recognised was through their working equipment’, Msiza lamented, pointing to the picture of a grave on which old working gear was still visible, along with a numbered plate.”

The Department of Mineral Resources, to which the Mine Inspectorate is attached, was working with the unions and the local council to try to identify the dead workers.

Slide from a presentation to Parliament, Department of Mineral Resources, 2015

Call for a memorial to recognise the sacrifices of mineworkers

Msiza stated that consideration was being given to the creation of monuments and the compilation of documentaries to reflect the undignified past of mineworkers dying in their droves on South Africa’s mines, which have been the foundation stone on which the economy has been built.

Over 69,000 mineworkers died in mine accidents from 1900 to 1993, and more than a million were maimed or seriously injured. This was a finding of the Leon Commission that reported to President Mandela on mine safety in 1995.

The high fatality rates persisted until recent years. The historian of Gold Fields, Roy Macnab wrote “In a ten-year period, from 1973 to 1983, no fewer than 8 209 people lost their lives in mine accidents in South Africa and nearly a quarter of a million were injured”. The average was 820 mine deaths per year!

In 2012, Wits University unveiled a tall statue of an “Unknown Miner” to mark the 90th anniversary of the founding, in 1922, of the school of mines as part of the University. (The School was established in Kimberley in 1896 and moved to Johannesburg in 1904.)

The former AngloGold Ashanti CEO Bobby Godsell spoke at the function. Mining Weekly reported him saying “that he did not think that the Unknown Miner sculpture was adequate recognition of the cost in blood and human lives of South African miners and more appropriate would be a structure like the Vietnam War Memorial, which honoured by name each of the more than 50,000 American troops who died in Vietnam.”

Establishing the names of the miners in the graves at Winkelhaak has proven impossible.

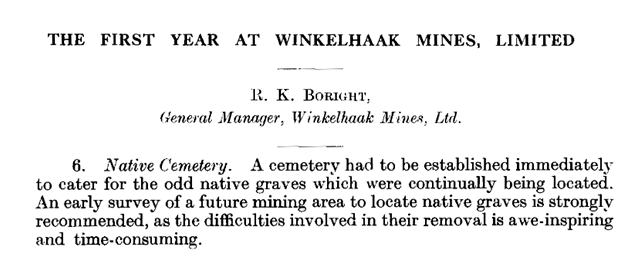

The Native Cemetery, Winkelhaak Gold Mines, 1955

The discovery of the Far East Rand goldfield was an extraordinary event. It has been described as perhaps the finest achievement of Union Corporation, the major mining house founded in the 1890s, which merged into Gencor in 1980. Highly secret prospecting activities after 1952 included new magnetic prospecting techniques using aircraft, before extensive drilling struck the Kimberley Reef near what is today Evander. Technical details were given by the geophysicist Oscar Weiss in his fulsome 1983 obituary of Alfred Frost, the geologist who made the critical discoveries.

Union Corporation appointed B.K. Boright, a mining engineer, as general manager of the first mine, on the farm Winkelhaak from December 1955.

Two years later, in May 1957, Boright presented a paper to the Association of Mine Managers of South Africa (AMMSA) in which he described the detailed tasks he supervised to build a new mine from scratch. He described his paper as “notes on the various problems encountered, such as housing, stores, workshops, etc. and it is hoped that they may, in part at least, be of use to someone who in the future my be faced with a somewhat similar task.”

Two early tasks were to build a “Native Hospital” and lay out a “Native Cemetery”. “Initially natives who were sick or injured were sent to the [Union Corporation] Group hospital at East Geduld Mines [in Springs] One ward, including its ablution facilities, was started at the same time as the permanent compound....A small mortuary was also built.”

Extract from a paper presented to the Mine Managers Association in May 1957

Boright later explained that “the manager of a new mine is faced with many non-technical problems which are, to put it mildly, time consuming.” He added a “very brief note” on “European and Native Graves”: “As stated previously, the question of farm graves can be embarrassing if not tackled early. In order to get permission to have graves removed, the following information has to be submitted to the Provincial authorities :

- Name of deceased

- Date of death

- Age at death

- Cause of death

- Location of grave.

- Where the remains are to be reburied.

- Permission of next-of-kin or relatives for the removal.”

It is thus possible that some of the graves in the Winkelhaak Cemetery are not those of mineworkers, but are the re-buried remains from graves that were disturbed during the building of the mine shafts, hostels and infrastructure.

Boright recorded that “No difficulty was experienced in obtaining native supply.” He added that “No local farm labour was engaged, as this would have caused considerable friction in the area.” [This would have been the farmers who would have been angered if the labour supply for their farms had been tapped by the mine!] “The residual farm labour population was given six months to find work and move to other farms.”

Questions without answers:

- Is the Winkelhaak Cemetery an extension of the “Native Cemetery” described by Boright?

- If so, how many graves are re-burials from graves made before the mine, and how many are of mineworkers?

- Winkelhaak recorded the information required on the graves that were found and moved. What happened to these records?

Visible in the centre of the picture, through the trees, is a chimney flaring off gases from the Sasol Secunda coal plant. On site, it is striking as it shines red through the cloud of Highveld pollution, on a bright sunny morning in August 2018. An eternal flame for the mineworkers buried across the plain at Winkelhaak. (Martin Nicol)

Martin Nicol studied economic history, has visited many mines and works as a researcher. All the information here is in the public domain.

Sources

- Boright, R.K. (1957) The first year at Winkelhaak Mines, Limited. Papers and discussions of the Association of Mine Managers of South Africa (AMMSA). 24 May. Available at thevirtualmuseum.org.za

- Creamer, M. (2012) Wits answers urgent call for Africa-based mining research. Mining Weekly. 28 March.

- Creamer, M. (2015) Documentaries on horrors of mining’s past mooted at Coalsafe. Mining Weekly. 12 March

- Davenport, J. (2011) South Africa’s first school of mines. 28 October. Also see endangered thread on The Heritage Portal

- DMR (2015c) Briefing to the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources. 14 October 2015. - Slide 18: Programme 2 Presentation (click here to download)

- Jones, J.D.F. (1995) Through Rock and Fortress: The Story of Gencor 1895-1995. Johannesburg. Jonathan Ball.

- Macnab, R. (1987). Gold their touchstone: Gold Fields of South Africa, 1887-1987 : A century story. Cape Town. Jonathan Ball.

- Union Corporation Limited (1974) The First Seventy-Five Years 1897-1972 Union Corporation Limited. Available at Wits Historical Papers [Accessed 21-Sep-18]

- 9. Weiss, O. (1983) The discovery of two goldfields: a tribute to an inspired mining geologist – Alfred Frost. IMM Bull., 924, 4-5

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.