The Johannesburg and Pretoria Guide, An Illustrated volume for Reference for Travellers, containing information of every character for visitors and residents, including Guide to all Points of Interest in and around Johannesburg and Pretoria, Description of Building etc. 2nd edition, published by Dennis Edwards of Johannesburg and Cape Town (1905), 373 pages, illustrated.

Recently two early South African guide books came my way and I thought this would be a good moment to alert heritage enthusiasts to the value of this type of rather quirky, now very out of date guide. Wouldn’t it be rather fun to use an old guide book to navigate the city and see what remains after the intervening century, and what has disappeared? An old guide book is a great source for heritage studies.

Historic guide books are now regarded as valuable sources of contemporary information about places, activities, architecture and buildings. The Edwards Guide, 2nd edition was published in 1905, and the preface admits its incomplete state, but states that its aim is to publish in “cheap format” a guide for visitors to the “golden city” (Johannesburg) and, as an afterthought, Pretoria. The guide contains 200 black and white illustrations of Johannesburg street scenes and buildings with the last 40 pages devoted to Pretoria. A guide book gives the earliest potted history of the city, looks backwards to signal proudly what has been accomplished, sets out the nuts and bolts of the town at the date of publication and anticipates future new developments.

Guide Cover

Essential to any guide are maps, but this book contains no maps or if there was a map insert it has long since disappeared. A guide book borders the space between collectable book and disposable ephemera. How many of us save the old 20-year-old first Lonely Planets guide that you used? These are functional throw away books to be discarded after the grand trip, though you might keep an old guide book as a souvenir. A particular collecting genre is the guide book, or publicity booklet or the birthday commemorative book or pamphlet for our cities. Such material is available for cities such as Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, Bloemfontein, Durban, Johannesburg and Pretoria. These guides could have been produced commercially or by a town or city publicity association or by the South African Railways and Harbours Administration. They date from a time when railway travel was romantic, novel and adventurous. If such items come your way, treasure them and try to build a specialist collection.

Here we have a guide to Johannesburg surviving for over 110 years and giving us an insight into the proud history and growth of the city. The photographs become an invaluable record of what Johannesburg looked like in the Edwardian era. Here is a picture of Joubert Park with the crowds enjoying the sunshine on a Sunday afternoon, there is a photo of the front of the still pristine General hospital with its Barnato Ward. The Rissik Street Post office in 1905 looks good as the backdrop to the horses, traps and cabs bringing people to the centre of the burgeoning town. In 1905 Auckland Park (established in 1888 by John Landau and named for his native Auckland in New Zealand) was still being promoted as a garden suburb with a lake, trees and park gates. The original farmhouse had been turned into a hotel and a lake constructed as early as 1890. Auckland Park is described as one of the most beautiful suburbs of Johannesburg within easy reach of the centre of the city via horse omnibus.

A Sunday afternoon at Joubert Park (The Johannesburg and Pretoria Guide)

For anyone looking for historical information on Craighall Park, the Craighall Park Hotel receives a promotional few pages as to its facilities and advantages, for those who wished to escape the town centre. It was an hour’s journey from the city. There are two good photographs of the hotel, which was once the residence of William Grey Rattray who owned the estate called Craighall in 1891. In 1902 229 plots of about an acre each were sold on auction sale on a 999 year lease basis and as Craighall was just beyond the new municipal boundary an advantage was “the avoidance of all Municipal Taxes” (information from Anna Smith, Streetnames, p 104-105). In 1905 the Craighall Park Hotel offered a beer garden, a pagoda, fine cuisine, a view of the Magaliesberg, luxurious bedrooms, its own electricity and boating on the Craighall Lake.

A chapter on the Clubs of Johannesburg kicks off with the Rand Club (oldest and top prestige club), but you could also choose the Goldfields Club (strong on chess and cuisine), the New Club (for the commercial moguls of the town), the Athenaeum club (more exclusive and based on school , civil service and university background), the Johannesburg Club (newly established and popular with 750 members), the Catholic Club (catholic spirit but open to all denominations), the Liederkranz Club (the premier German Club), the Trades Hall and Workmen’s club (located in Commissioner Street, this was the meeting place for the many labour unions of the Witwatersrand), and the Young Men’s Christian Association (promoting moral character and welfare of young men).

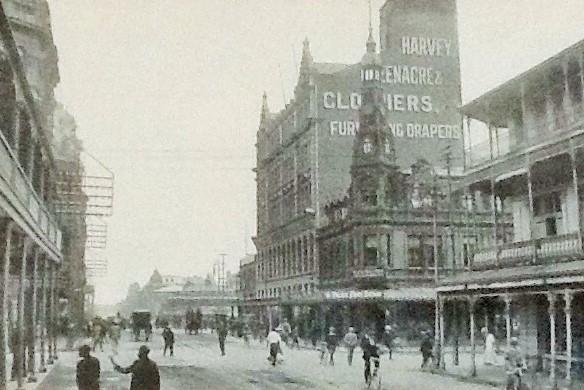

The book includes a thumbnail sketch of the early history of the discovery of gold and the sale of stands (in 1886 the first sale of building sites raised 13 000). In 1905 the main means of transport in the town were rickshaws and horse drawn cabs and the cab fare from Park Station to Staib Street in New Doornfontein would set you back one shilling per passenger (assuming two in the cab, and economies of scale started with three passengers). Johannesburg of 1905 is described as having an unprepossessing appearance for the new arrival: “Huge square buildings of an irregular height tower over a foreground of small galvanised iron houses”. The notable streets were Pritchard, Eloff and Rissik Street with the post office on Market Square (one of the largest in South Africa) described as “one of the first necessities of civilized life”. Markets were held twice a week on Market Square. But the street of Johannesburg was Commissioner Street, a broad handsome thoroughfare of two and a half miles long.

In 1905 Corner House or Eckstein Buildings was nine stories in height, dominating the town and was “the highest erection in South Africa.” The real usefulness as a source is the detailed description that follows on the construction details of Corner House with its steel frame, five lifts, each floor having a fireproof strong room and electric lights. One can use this guide to walk along Main, Harrision, Eloff, Market and President Streets to pin point exactly where the principal shops, offices, banks and business establishments stood and by 1905 were permanent. In 1903 the municipal area extended over eighty one square miles and the total population was 158 580 people. Evidence that in the post Boer War period Johannesburg considered itself a well-established town was shown in the reach of facilities and services: it boasted Joubert Park, the Milner and Herman Eckstein Park and Zoological collection, Klipspruit Farm, plus ambitious plans for an electric tramway and lighting schemes, placing telephone wires underground, managing the water supply via the Rand Water Board.

The Corner House in 2012 (The Heritage Portal)

The throbbing heart of the town’s economy was the gold mining industry and the visitor is informed that it is not difficult to visit a working gold mine. There is another valuable insight with the details of the dividend, tonnages milled, stamps working, yield and financial records for about 35 gold mines. The enormous wealth of the Witwatersrand gold mining industry lies hidden behind the simple figure that by 1905 the total value of the gold output amounted to 138 million pounds sterling. This was an astounding record. There are some superb photographs of the mine headgears of some of the leading mines of the era. The central controversy of the year 1905 was the question of the introduction of Chinese contract labour to the mines and the key argument was that the importation of Chinese “coolie” labourers would mean increased outputs and a rise in the employment of white labour (to 17000 white employees) plus another 34 000 “natives”. The chapter concludes that ‘in all labour there is profit’.

The schools of Johannesburg in 1905 show a strong religious presence, particularly of the Catholics with the Marist Brothers’ School in Kock Street, Joubert Park, the Convent of the Holy Family in Parktown (there is a photograph that shows the main building which you would still recognize today), St Mary’s college in Belgravia. The Jeppestown Government school became Jeppe Boys High and the Boys’ High School located at Barnato Park later became King Edward VII School for boys. The Technical Institute situated at the corner of Plein and Eloff Streets offered a surprisingly wide range of practical courses and training in mining, geology, physics, chemistry, architecture, building, carpentry and modern languages. It was another ten years before the campaign for Johannesburg to establish its own university gained traction.

The building in Belgravia that once housed St Mary's School (The Heritage Portal)

As you delve into this Johannesburg guide the realization dawns that it is a publication that must have been financed by the support of covert advertisers who were given their due advertorial pages. This material is now an incredibly useful archive of the types of business in engineering (electrical, a safe company, lighting, gas, construction, steel frameworks), wholesale and retail businesses (drapers, milliners, general merchants, stoves, furnishing, ironmongers, saddlery and harnesses, outfitters, shoe merchants, warehouses, cabinet makers and furniture, auctioneers, druggists, photographic dealers, jewellers and watchmakers, grocers, coach builders). There is even an advertorial for a beauty business, Madame Whitmore. I loved the response to the casual visitor’s lament that people in Johannesburg do not heat their houses and that this was now being revolutionised by a heating firm, J W Taylor. You could even order a locally made billiard table in Johannesburg. Then there were the wine and spirit merchants and breweries who ensured that the men of the town quenched their thirst. There is a photograph of “Thoma” Brewery located in Braamfontein and South African Breweries’ Castle Brewery extended the reach of an already national company to Johannesburg.

Johannesburg citizens in 1905 were keen on Saturday race meetings which took place at Turfontein, Auckland Park and Sans-Souci. And a chapter on racing with rare photographs of the crowds on the grandstands shows that racing and betting on the horses was not just the sport of kings.

Johannesburg hotels and cafes were ubiquitous. The ‘new' Carlton Hotel in Commissioner Street was the largest and smartest but then there was “Heaths”, the Grand National, Long’s, the North-Western, the Hotel Victoria, the Goldfields, Sydenham House and the Central all with well provisioned dining rooms, warm beds and welcoming bars. A feature of life in Johannesburg was the large number of cafes and restaurants; for example the Barrow Green Café included a tea room, a dining room and a rustic outdoor tea garden.

The Carlton Hotel (The Johannesburg and Pretoria Guide)

The delights of Pretoria are featured in a much shorter final section. The impression given that the sleepy capital of the old Transvaal was being dragged into the twentieth century under British administration and new developments. In 1903 the well-known industrialist and politician, Joseph Chamberlain visited to lay down to the Boer generals the British expectation that they should abide by the terms of the Peace Treaty. The Palace of Justice was still regarded as an architecturally fine building as was the Raadsaal. Kruger’s portrait had been removed and Chamberlain reassured his Pretoria audience that the capital would never be removed to Johannesburg. In 1905 the key sights were the new Government buildings on Pretoria Street, the Police Station, the Magistrate’s court and Church Square. The cultural hub of Pretoria was the Transvaal Museum with prize exhibits being old Boer military relics. In some desperation the guide highlights the Pretoria cemetery and the graves of the Kruger family. The alternative was to visit Pretoria’s churches, schools, the synagogue, the public library or the Zoological Gardens. Not too many Pretoria businesses feature in this guide book but perhaps the most interesting was a company called C Basson and Co, which styled itself as “booksellers, stationers and importers of Fancy Goods”. The photograph of the interior of the shop shows an emporium in which one could have browsed for hours.

The Raadsaal in 2014 (The Heritage Portal)

In summary, even without maps, this 1905 Edwards’ Guide to Johannesburg and Pretoria, is a rich mix of turn of the twentieth century photographs and information. Peace had returned, the Transvaal was a British Colony, business interests were paramount and Johannesburg’s mining wealth assured a bright economic future for its citizens. This was a town (city status was still some two decades away) of confident ambition, effective municipal innovation and civic pride which could all be financed through the renewed prosperity. In contrast the more conservative established Pretoria, with its older well rooted capital and cultural city feel needed reassurance and was confronting some doubts about its future. For both cities wise city fathers and very different styles of leadership were needed in the Edwardian decade.

I am now in search of the First Edition of the Dennis Edwards Guide to Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.