Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Of all the remaining old houses on the Sunnyside South campus in Pretoria, one seems uglier than the others. It is cheaply built, without a scrap of architectural merit. This is Building 20, now abandoned and full of junk.

The west side of the Sunnyside South ‘ugly house’, also known as Building 20 (Sue Taylor)

Between 2003 and 2008, this derelict house was lived in by the builders doing construction work at the Sunnyside South locality. While the western section of the house they occupied was pretty horrible, the eastern side of the house seemed even more unpleasant and industrial in some way.

“This place is haunted,” a young security guard told me recently. The young man then explained that the building was once used as a mortuary and that sometimes ‘ghost tours’ visit the house at midnight. There is very convincing blood spatter on many of the interior walls.

I set out to investigate the circumstances behind the guard’s statement. At first, I studied aerial photos and satellite images and examined the heritage report and Sunnyside campus Master Plan (Cultmatrix 2013) looking for any mention of such a bizarre function for Building 20. I could not find any mention of a mortuary in this locality. Even academic literature offered no clues. Perhaps this is one of those things that no-one wants to reveal.

A quick history of the Sunnyside South suburb

Farms which became the suburb of Sunnyside were incorporated into the City of Pretoria in 1890. Some of this land became the Sunnyside South campus, which from 1902 to the 1980s, housed the Pretoria Normaal Kollege and after that, the Pretoria College of Education. In 1992, UNISA bought the land and by 2003, the Enoch Sontonga Conference Complex (previously known as the UNISA Sunnyside Campus Conference Hall) had been renovated and the new Es’kia Mphalele Student Registration Centre was completed in 2008.

Building 54, one of the 'prettier' houses on the Sunnyside campus (Sue Taylor)

Aerial photographs of 1948 show that Building 20 is not yet built and that the odd-shaped stand is vacant, while the rest of the Sunnyside South area is fully built up with residential houses at this time. Most of the houses on the Sunnyside South site were built in the 1930s, but Building 20 was built in 1954, in a rather dismal mid-century ‘ranch’ style. Up until 1991 (Figure 15, Cultmatrix report 2013), most of the original houses on the Sunnyside South site still remained, about 50 houses in all. It is unclear whether these houses were still lived in at this time, but probably not. Between 1991 and 1992 there were significant demolitions, reducing the number of houses to 20, presumably because the other 30 houses were in a very bad condition. It is a puzzle why ‘ugly’ Building 20 survived the mass demolition, while other ‘prettier’ buildings were removed.

From around 2003 until 2008, builders occupied Building 20, judging from salary slips found in the house, and they carried out various renovation and construction projects. After the Es’kia Mphalele Student Registration Centre was completed in 2008, the builders vacated the house, leaving behind their discarded possessions to gather dust. The builders left behind shoes, mattresses, clothing, work boots and work gloves, and beer bottles by the hundred. There is also some graffiti. The whole setting is very disturbing, yet it is a compelling archive of the men who lived there while building the various new developments between 2003 - 2008.

Junk left behind by the builders. This small tableau has remained exactly the same between 2016 and 2021. (Sue Taylor)

When I began photographing the Sunnyside South site in 2010, most of the original suburban houses were long gone and those that remained had been abandoned for many years. The entire site was much neglected, vandalised and overgrown, with big trees flourishing in previously open areas. Around 2017, the stripping of the remaining houses accelerated, resulting in the windows, doors and roof sheets vanishing, opening up the buildings to the weather and decay. Three of the houses were destroyed by fire at this time.

Never just an ordinary house

Building 20 itself is very different from other houses on the Sunnyside South Campus. Rather than quaint Victorian, Edwardian or Art Deco, it is, as mentioned, the only house built in a banal mid-20th century ‘ranch’ design and is located on a badly shaped stand on the corner of Piet Uys and Normaal streets. The shape of the stand may have meant that the back wall of the house had to be built very close to the boundary wall, as well as the front of the house being close to the road, in order to make the house fit the stand. Effectively the house has no garden. In its early days, the house would have faced an open park, but now that open land is occupied by the new Es’kia Mphalele Student Registration Centre. It has not been used as a family home for a very long time.

The front door leading into the lounge of the house. This door leads almost directly out onto the street, with no front garden although there may have been a low wall originally. It is surprising that this door and door way is still intact. (Sue Taylor)

That secret bricked up room

There are various building modifications that lead one to speculate that part of the house was equipped as a temporary or makeshift mortuary. Building 20 may have originally had its own garage with a set of garage doors, but as can be seen in the image below, the wall directly in front of the paved driveway is now bricked up with small high windows. It is also possible that this room started out as a garage, but that was expanded and modified at some point. What is unusual about this room is that it is built right up against the wall of a much older servants’ quarters complex. At the back of Building 20, there remains a gap between the house and the wall of the servant’s quarters, implying that the bricked up front wall is a later modification to the house.

Building 20 and the large bricked up room (centre) abutting the earlier 'servants' quarters' to the left (the higher wall). This large room is also the room that lies behind the mysterious bricked up door inside the house (see below). At the moment, it is not possible to gain access to this room. (Sue Taylor)

The roughly bricked up doorway which leads into the mysterious room. The hidden room may have contained forensic facilities. Ahead, towards a back door, an ominous ceramic sink is housed. The area surrounding the ceramic sink was originally tiled from floor to ceiling with white tiles. (Sue Taylor)

That formidable white wall

The substantial curved wall in front of the house suggests that some activity needed to be discreetly hidden. This wall is an addition, although difficult to date from aerial photos. The curved wall is not present in a 1964 aerial photograph, but is visible (only just) in a 1991 aerial photograph (Figure 15 of the Cultmatrix report). The doorway behind the curved white wall leads into the area of the house that contains the large ceramic sink, a mysterious bricked up doorway and refrigeration cabinets with cables. One can speculate that the wall might have been built in the 1980s during the political unrest and States of Emergency in South Africa. There is also a huge amount of junk in this section of the house, remaining untouched since 2010 (author’s observations).

Building 20, showing the east end of the house and the bricked up entrance to what may have originally been a garage. Also prominent is the curved white wall that screens a doorway and parking area from public view. The entrance with the refrigeration cabinets visible is behind the white curved wall, Google Earth Street View, 2017.

Something not right in this house

As my first explorations of this house in about 2010 were about the vanished ‘builder men’ and the junk they behind, I didn’t take much notice of the rest of the house. In any case, the east side of the house was very dark and unpleasant and nothing much could be seen in the gloom. In 2017, an outside wall was knocked down and light now floods into this area. One can easily see the equipment for the macabre use of the house as a mortuary.

Inside the eastern section of the house there is a large metal cabinet with six doors and a massive system of what look like electrical cables. The metal cabinet is a refrigerated mortuary cabinet with six doors. There are no manufacturer's marks or serial numbers on the cabinet which could have helped date the equipment. What is missing from the refrigerated cabinet is the motor needed for refrigeration, so presumably this item was removed (stolen) in the past. A large double-basin ceramic sink seems ominously out of place if Building 20 was last used as a family home.

The refrigerated mortuary cabinet (right) inside Building 20 (Sue Taylor)

The laboratory-style ceramic sink which has remained un-vandalised (until 2021). Evidence of the fire that broke out in this section of the house prior to 2010 can be seen. (Sue Taylor)

In 2021, Building 20 is much neglected, but strangely, the light fittings, toilets, basins and baths and taps remain in place, although no longer functional. Also still remaining are the windows and doors, cupboards and some furniture. This is surprising as in the other remaining Sunnyside South houses, everything useful has been stripped and removed years ago.

Anomalies in Building 20

There are various anomalies in Building 20 which could be resolved by looking at the building plans. These anomalies include a number of bricked-up rooms which may or may not have provided the washing and office facilities for a putative mortuary and its staff. There are differences in the quality of the bricks and brickwork on some of the walls, indicating some are more recent than the original 1954 structure. Also, examining the building, one does not see any unusual ventilation or drains that could relate to the functioning of a mortuary. There is also no electricity substation outside the building to provide a reliable electrical supply to the facility. These must all have been removed before 2010. If this is true, why were the refrigerated cabinets not removed at the same time? It’s all a bit of a mystery. Building 20 also suffered a fire at some point before 2010, but instead of this being an opportunity to knock the house down, the damaged roof sheets and timbers were replaced.

What is also strange is that there is no evidence of security for the mortuary. The back door next to the ceramic sink shows no sign of reinforcement, nor do any of the windows, beyond ordinary burglar bars. There is no fencing or ‘keep out’ signage. Anyone can walk in. It is likely that when the putative mortuary was in use, the Sunnyside South site was deserted and that security guards discouraged casual vagrancy.

Flimsy security at the back of Building 20 (Sue Taylor)

Medical facilities can get overwhelmed

As we know from the Covid-19 pandemic, hospital facilities can become overwhelmed by the sick or by casualties during a disaster or emergency, and contribute to intensifying the disaster. First hospitals become overwhelmed, and then mortuaries, morgues, forensic facilities, begin to creak under the strain of large numbers of the dead, both in terms of overworked mortuary workers, as well as the limits of the facilities themselves. These days, there are options like refrigerated tractor trailers which serve as portable, temporary morgues, and can be taken anywhere to respond to disasters, but in earlier days, this type of equipment was not available.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, temporary morgues have been set up in many countries, often in former aircraft hangars, churches and community halls, even in car parks, as countries struggled to store bodies. In the UK, a large regional mortuary facility was established at Ruislip, using tented facilities with banks of refrigeration units, making the process of storing bodies more streamlined. Spokespersons at Ruislip reassured the public that there are dedicated trained staff who will ensure the dignified treatment of those who have died and been taken to these facilities.

During the two South African States of Emergency between 1985 and 1990, none of this would have happened, even if the technology was available. The government would have been decidedly unprepared and unwilling to deal effectively and caringly with high numbers of deaths caused by their own draconian apartheid and State of Emergency policies and laws.

Quelling black political resistance in the 1980s

Black political resistance in South Africa had been building up since the 1970s, and in the 1980s the banned African National Congress (ANC) stepped up its campaign of violence and protest. There was a growing crisis for the ruling National Party as ANC attacks in Pretoria escalated with many bombings of key state facilities in the city. In 1985, a partial State of Emergency was applied to 36 strife-torn magisterial districts in the Eastern Cape and the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vereeniging area (now part of Gauteng). This didn’t really work to quell the unrest and during this time, black protest and violent resistance increased, manifested through protests, boycotts, township uprisings, funerals which became political gatherings, killings, bombings, hand-grenade attacks of state facilities, all dealt with by the deployment of thousands of police and soldiers in the townships, with many police massacres. Police used tear gas, rifles and shotguns against rioters who were armed with rocks and petrol bombs but black resistance continued throughout the country and led to a national State of Emergency being declared which lasted from 1986 and 1990. This was effectively martial law.

The two States of Emergency allowed the white government to deploy the South African Police (SAP) and the South African Defence Force (SADF) to violently repress any resistance against the state. The States of Emergency allowed for detentions, repression and assassinations and a draconian crack-down on growing black resistance in South Africa. Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial and activists were killed, tortured or made to disappear, while the state wanted to keep the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity by media repression (SA History Online).

Deaths during the States of Emergency

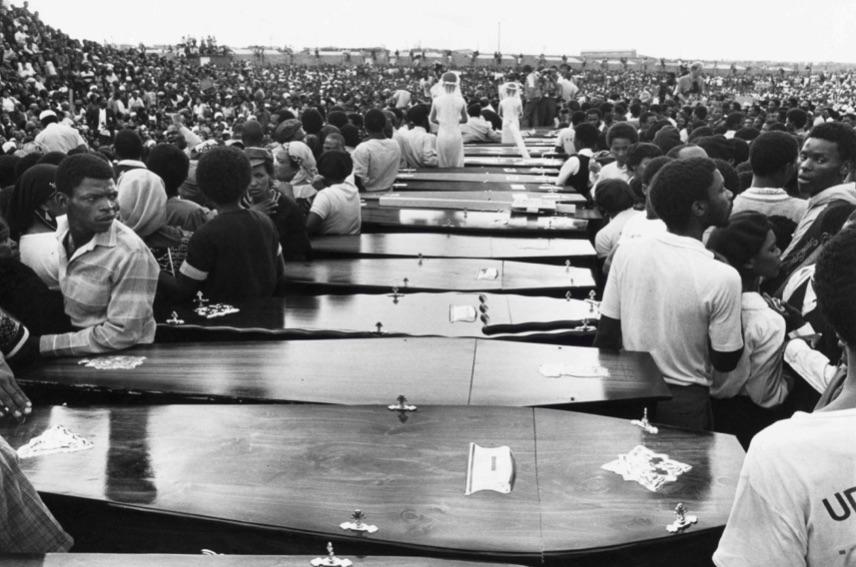

During the six years of the two States of Emergency, many thousands of people were arrested, and hundreds died in the violence or in police custody. As more black people were killed by the police, funerals became opportunities of protest and more killing would result as police fired on processions. For example, more than 30,000 people attended the funeral for the Guguletu Seven on March 15, 1986, despite regulations that prohibited funerals and other mass gatherings.

A mass funeral held in 1985 at Kwanobuhle Stadium for 35 victims of the Uitenhage Massacre in Eastern Cape (photographed by Gideo Mendel/Corbis) in article by Kenneth Good, 2020

South Africa’s medical and mortuary facilities overwhelmed?

During the two States of Emergency which lasted from 1985 to 1990, news crews were banned from filming and reporting on political unrest, with the South African government intending to prevent the spread of information about police brutality and the government’s failure to contain the wave of social unrest. An estimated 26 000 people were detained just between June 1986 and June 1987 (SA History online, 2019) and the total number of deaths from September 1984 to October 31, 1990 was estimated at 8577, mostly black South Africans (HRW 1991).

It is likely that the country’s medical and mortuary facilities were overwhelmed during this time, with many hospitals turning away victims of the violence. As an example of the growing number of casualties and the strain that medical facilities began to experience, the hospital at Sebokeng township near Vereeniging was “forced to divert wounded to other places after 200 wounded people had been admitted” (Cowell 1984). This must have been the case for other hospitals. Many of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) submissions were about families searching for their loved ones in hospital mortuaries without much help from police or the medical fraternity. Responding to an increase in deaths during the States of Emergency, additional mortuary resources would have had to be made available, staffed with medical examiners, coroners, hospitals, and funeral service providers.

By 1989, the emergency laws were being relaxed, and in 1990, the Pretoria Minute was signed as a truce between the South African government and the ANC. In 1994, the ANC came into power after South Africa’s first democratic election and Nelson Mandela was sworn in as president of the country.

Security legislation and censorship

Security legislation and media censorship in the 1980s would have meant that it was not possible for journalists to report on the state of medical facilities during the States of Emergency, and medical professionals would have had to maintain a silence on how the increasing numbers of dead bodies were dealt with. In some cases, records of the dead were not kept and it was difficult for families to find their loved ones. There must have been huge problems with unidentified bodies and the need for pauper’s burials. Some black families are still looking for their dead to this day. Also, in the transition to democracy, much of the historical record about the apartheid machinery was deliberately destroyed.

Graffiti on the walls of Building 20, here used to indicate the ugliness of censorship (Sue Taylor)

Evidence of supplementary mortuaries

Should there no longer be archival records about informal or supplementary mortuaries, the physical evidence in Building 20 at the Sunnyside South site indicates that a hidden mortuary was in operation during the mid-1980s. Evidence includes modifications to the house and the bizarre equipment. The mortuary’s likely function would have been to accommodate the increasing numbers of the dead during violent protests in the 1980s in Pretoria. It would not make sense to argue that the tiny mortuary was in operation during some other recent period of South Africa’s history.

End of the national State of Emergency

When the national State of Emergency ended, the equipment remained in place until now, some 31 years later, unacknowledged and seemingly forgotten. The equipment is visibly damaged and no longer functional and could not be restored pending another emergency of some kind. This means that Building 20 has not been kept on ‘standby’ as a working emergency facility. Perhaps no-one has come forward to claim the facility. This said, it is indeed odd that the metal cabinets and electrical infrastructure have not been looted for scrap metal.

In 2010, when I began taking photographs, Building 20 was clearly long abandoned, even by the builders, but the fridges and other mortuary infrastructure remained in place and they remain there to this day, absolutely unchanged, even to items of trash on the floor. The refrigeration equipment is in an area that is accessible to the public, with no ‘keep out’ signs, but no-one has gone into the building to clean up the rubbish or removed the mortuary equipment. One has to ask why the mortuary facility was not properly decommissioned and the entire infrastructure linked to the mortuary removed.

In 2003, thirteen years after the end of the national State of Emergency, all 20 remaining houses on the Sunnyside South site were long abandoned and there was no-one permanently living on the site. Then, as new educational developments got underway, teams of builders began to reside in the west side of Building 20. Even though a mortuary was no longer in operation, it must have been disconcerting to live in a building where a mortuary had recently been in use and equipment to store the dead was still in place. Apart from the spookiness, being in the presence of a mortuary can expose people to infectious diseases, chemicals and psychological stress. The current South African Public Health Act 61 of 2003 now acknowledges the negative impact of mortuary facilities on public health.

A hidden-in-plain-sight 1985 State of Emergency mortuary found?

One can argue that Building 20 was modified for use as a police mortuary or an overflow mortuary facility for one of the local public hospitals (for example, the nearby HF Verwoerd Hospital in Pretoria) and the equipment remains on site, 31 years later. The supplementary mortuary would have been established to cope with increasing numbers of the dead as black protest and police violence escalated during the two States of Emergency.

I have not yet been able to find published reports about the way the South African apartheid government responded to the medical crisis that the two consecutive States of Emergency must have created, and the pile-up of dead bodies during that time. Looking at the Truth and Reconciliation website, the main activity to deal with the injured and dead seemed to be moving them around to other facilities, meaning that families couldn’t find their loved ones. It seems likely that eventually the government had to build or repurpose many other existing facilities as temporary morgues to cope with the dead, perhaps in a similar way as evidenced by Building 20. The other States of Emergency mortuary facilities remain ‘hidden’ or in other ways were made to ‘disappear’ from history.

I welcome new evidence and alternative explanations of the 'Sunnyside Spook House'.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (and what trash can tell us about society), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes and buildings. She has just finished a three year stint as a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- Campus Master Plan and Heritage Report (2013) by Cultmatrix Heritage.

- SA History online. State of Emergency – 1985.

- SA History online (2019). States of Emergency in South Africa: the 1960-s and 1980s.

- Cowell A (1984). 14 Die in Riots in Black Areas of South Africa. The New York Times.

- Health Infrastructure's Living Library (dated 2019).

- Sky News. UK's largest temporary morgue set to open with high deaths to continue 'for some weeks'

- Kenneth Goog (2020). The apartheid wars: freedom for perpetrators.

- Between States of Emergency: Photographers in Action 1985 – 1990. Nelson Mandela Foundation.

- HRW 1991. The Killings in South Africa: The Role of the Security Forces and the Response of the State. Human Rights Watch. January 1991. ISBN 0-929692-76-4

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.