Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The battle of Kambula (29 March 1879) is the definitive battle of the Zulu War. After the disaster at Isandlwana, when Lord Chelmsford’s Centre Column had temporarily ceased to exist, the focus of the Zulu War had turned to Evelyn Wood’s Column in the north. Not that the British had yet fully learned their lesson about underestimating the Zulus. The Northern Column suffered two disasters – one at Ntombe Drift (12 March) and the other at Hlobane (28 March), before the rampant Zulu army tried their luck on the British base camp at Kambula the following day.

Now situated in a forestry reserve north-west of Vryheid, the area is remote and difficult to reach, especially in a low-slung car or in the rainy season. The signage hasn’t been spruced up for some time either, and the only badly faded sign says “Nkambule”. But don’t be deterred – it’s the right place. The site of the battle is largely unspoilt. Fragments of commercial plantations only marginally spoil the integrity of the site, which is otherwise as pristine as the day it took place.

A stone plinth on top of a small hillock marks the site of Evelyn Wood’s redoubt, and one can clearly see the trench dug around it in the stony ground. If you look about a mile to the north-west you will see the monuments in the British cemetery. To your left (or West) is the site of the laager, with the artillery positions on the saddle between the knoll and the laager. Behind you (or south) is a flat piece of ground where one of the cattle kraals was placed before the ground plunges away into the Nkonjane River valley.

British cemetery at Kambula (Talana Museum)

The trick when fighting the numerically superior Zulus who lacked firepower was to shoot at men from a couple of hundred yards away, long before they, in turn, could get within striking distance with their spears. The rules, then, were, firstly, do NOT let them get within range. Secondly, do NOT run out of ammunition, and you'd be home and dry.

The battle of Kambula is a classic example of a textbook action

The British occupied a west-east running ridge line with a central redoubt. The position had been fortified, trenches dug and wagons laagered during a period of some weeks. The tactics were simple. The British managed to goad the two Zulu “horns” into attacking piecemeal, uphill, over ground devoid of cover, into the withering firepower, including a battery of artillery, of a really annoyed bunch of Brits. When the Zulus finally broke, the mounted men rode out to chase them down, killing hundreds in a running battle over 20 miles right up to Zunguin Mountain. Casualty figures were 29 British and Colonial troops dead, while the Zulus suffered an estimated 2000 dead.

It is my favourite battle site in this part of the world. Remote, pristine, evocative and atmospheric, you will almost certainly stumble across a spent cartridge, tent fitting, lead bullet or square-faced gin bottle. But beware – the use of a metal detector or removal of any artifact is “verboten”.

Opening Moves

Douglas Rattray of Fugitive’s Drift responded to an e mail from Hugh Scott (nomad131@aol.com) concerning a query about the possibility of buried British ordnance at “Shepleigh” farm at Rorke’s Drift by steering him in another direction – the location of the mass grave/s of Zulu warriors at Kambula.

The prevailing attitude of the British and Colonial troops under Chelmsford’s command towards their Native allies, mostly Basuthos and Swazis, was one of almost casual contempt and indifference. They were utilized because of their local knowledge, the fact that they spoke the native languages and that they were ancient enemies of the Zulus. Their other attribute was that they were both cheap and expendable.

So far as their enemy was concerned, Zulus were reputed to be more war-like than most of their contemporaries but that remained to be seen. They should be easy meat – somewhat akin to hunting pheasant

The battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 changed all that. The British, traumatized by the loss of and subsequent ritual mutilation of 1 357 men, had only one emotion in mind from then on in – revenge. Zulus were not considered to be a worthy enemy – “the noble savage’. Instead, they came to be regarded as murderous vermin, to be ruthlessly hunted down and killed without mercy.

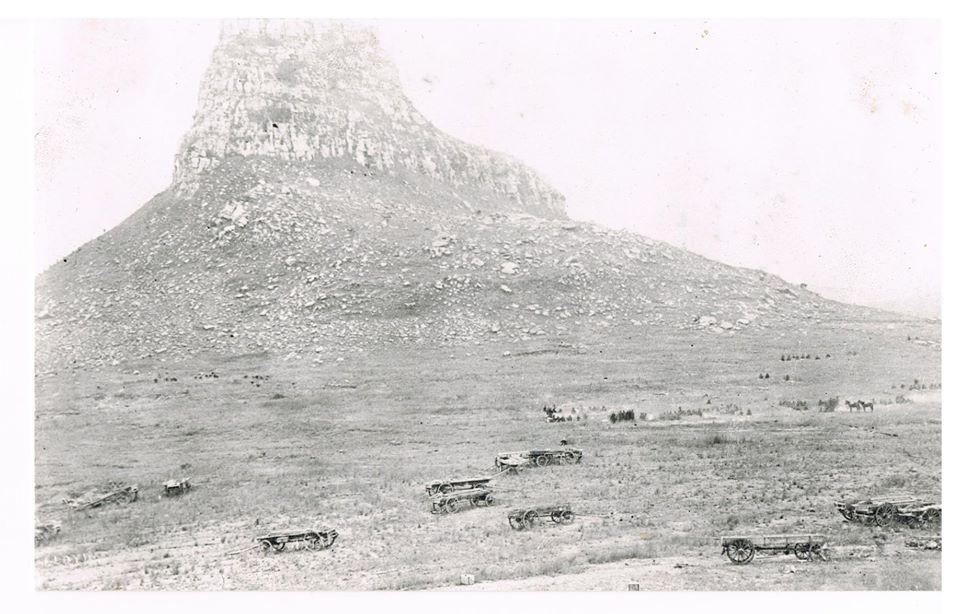

Isandlwana Hill (Talana Museum)

We know that Zulu dead were buried after the battle of Rorke’s Drift, but this was not out of respect for a gallant foe. It was for purely sanitary reasons as the site was intended to be occupied for a couple of months afterwards. If their columns were on the move, such as after the battles of Nyezane, Gingindlovu and Ulundi, the British simply left the Zulu dead where they fell and the column moved out of olfactory range, leaving the clean-up to the scavengers - vultures, hyenas and jackals.

If Wood’s Column moved off towards Zululand soon after the battle, it is unlikely that they would have bothered to bury the Zulu dead. However, according to “The Field Operations Connected with the Zulu War” at page 90, Wood was still based at Kambula in mid April. Lord Chelmsford visited him in early May, and by mid May Wood’s column was on the march to its new base at Conference Hill.

Since Wood only moved off site some six weeks after the battle, it is highly likely then that he would have been forced to bury those Zulus killed in close proximity to his laager site. He wouldn’t have bothered with those killed in the pursuit and they would have been left in situ. According to “Blood on the Painted Mountain” on page 200, “the next morning, James Francis, a colonial officer, walked around the camp and within a radius of 800 yards counted 800 Zulu dead”.

Book Cover

It is therefore fair to conclude, that these 800-odd Zulus, at least, would have had to have been buried near the battle site.

Location of the Zulu Burial Site/s at Kambula

If some 800 Zulus were buried at Kambula, then where is their burial site? Nothing remains to point us in the right direction. “Blood on the Painted Mountain” states categorically that “a pit, 200 feet long and 10 feet deep, was dug to accommodate the dead”.

Commandant Schermbrucker confirms that “we buried the Zulu dead with full military honours”. I personally doubt the veracity of that last bit. I doubt if the British felt any respect for the dead - just satisfaction that they were indeed dead.

Mitford says that, upon his visit to Kambula, he noted "Further down the slope, three or four dark spots of a different growth show places of sepulchre of the Zulu dead who were buried in hundreds after the battle"..This is, of course, contradictory to Ron Lock’s information, but raises the questions – where was he standing at the time? In what direction was he looking? And which slope was he referring to?

If one stands in Wood’s old redoubt and looks north, immediately in front is the stream and vlei that so nearly spelt the end of Colonel Russell during Buller’s foray to goad the inGobamakhosi into a premature attack. One can discount a burial site anywhere near the camp’s water source, for fear of contamination, so it’s unlikely to have been there.

Slightly to the east is the rocky outcrop used as cover by the retreating Zulus. However, it is also close to the stream and would constitute hard digging into the rock. So I would discount that place as well.

If one then swivels to look due east, one would be looking over the site of Wood’s original laager, in what is now a piece of forest beyond the football field. Wood had been forced to move his camp to its new position because of the pollution caused by the excrement of thousands of animals and men over an extended period.

Page 185 of “Blood on the Painted Mountain” shows an interesting and detailed picture of one of Wood’s camp sites prior to the move to Kambula. Sanitary arrangements would have been rudimentary at best. An ox will produce up to 35 kilograms of dung per day. A man – well, some of us would produce a kilogram or two. Multiply that by several thousands of animals and men by several days, and you get what the Victorians understatingly called “foul ground”.

Because this ground had been churned to muck over a couple of weeks, thus making digging easier, and is in full view of the camp (making guarding and supervision much easier), I believe that this would be a likely spot for a mass grave or two.

To the south, there is a small plateau and then the ground slopes very steeply towards the Nkonjane River valley. Although it would have been expedient to simply toss the Zulu bodies over the cliff and into the valley below, again one must be careful not to contaminate one’s water supplies. Plus the smell of decomposing bodies would have been trying. So, a possible alternative, but doubtful.

To the west, beyond the laager site and the old camp refuse pits, is another distinct possibility.

To the northwest is the British cemetery, beautifully kept and studded with monuments. I would discount that site too – there is no way the British would bury the Zulus next door to their own honoured dead. Maybe further down that same slope, but then that area would have been out of Mitford’s line-of-sight.

And so we swing back to the stream and vlei to the north.

Monument to the dead Zulu soldiers (Talana Museum)

Conclusion

That gives us two choices for a possible burial site. Either east of the redoubt, towards the forestry plantation and old camp site, or west past the laager site and refuse pits. Wherever Mitford was standing at the time, he says “down” the slope. Since the ground slopes UP the ridge to the west, if one takes Mitford literally, that would put the possible grave site to the east, on or near the site of the old camp.

One of these days I’m going to take a walk through that forest. I suspect, though, that intensive cultivation over many years will have obliterated any signs of a possible burial site, if indeed it was there in the first place.

But that’s my guess.

Pat Rundgren at Kambula (Talana Museum)

Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.