Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Last weekend (Sunday 3rd February 2019) I joined ten heritage stalwarts of Kensington who came together to acknowledge history and pay homage to a remarkable war memorial and the men whose names once appeared on it. We gathered because during January 2019 the memorial had been extensively and probably irreparably damaged. Erica Lűttich had together with her students created an art installation by wrapping the memorial in cloth. We Johannesburg residents and heritage protectors are saddened, shocked and appalled by this latest assault on one of Johannesburg best known war heritage landmarks with a rich history. It is one of Johannesburg’s earliest war memorials, erected in 1905 - making it 114 years old this year.

A damaged section of the memorial (The Heritage Portal)

Missing plaques and graffiti (The Heritage Portal)

The memorial wrapped in cloth (Kathy Munro)

What is this memorial about? Then and now. This is the memorial to the men of the Scottish Horse regiment, who lost their lives in the South African War (Anglo-Boer War), an imperialist, colonial war and civil war that did so much damage to South Africa because of the insistence on British control and rule, expanding the empire and managing the gold mines. The memorial is testimony to the emotions and aftermath of the South African War. Many ended up impoverished and the legacy of the war was a bitter one. Apart from the casualties of Boer men, women and children, the British casualties amounted to 55 000 men killed in action, dead from other causes or wounded. This was not just a conflict of English and Afrikaner, black people suffered too and it is only recently that their engagement, pain and loss has been acknowledged (click here to view a powerful article by Eric Itzkin on how the war has been commemorated over the decades). It is interesting to note that this specific memorial included the names of four black soldiers who were scouts with the Scottish Horse.

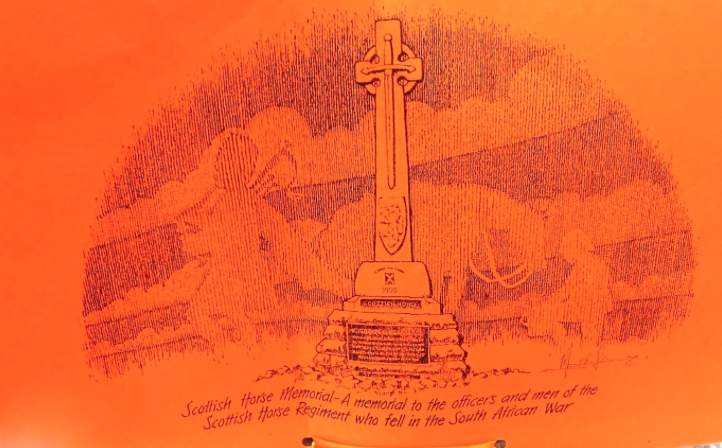

The state of the memorial and vandalism here and in Bez Valley. The memorial has been vandalised in the past. Bit by bit more of the memorial has been under attack and today there are no brass plaques or permanent inscriptions other than the lettering etched in stone: Scottish Horse. It is only the flimsy, defiant orange thick cardboard poster pictured below that explains what the memorial is about.

Orange cardboard poster

The state of this memorial and the destruction of the First World War Bez Valley Memorial generates a debate and raises deep questions about the value of preserving a century plus year old war memorial.

Vandalised Bez Valley War Memorial (Kathy Munro)

Should we preserve War memorials? What is the purpose and why hang on to a memorial to these men killed during a civil war in South Africa? The South African War today is seen by many and dismissed by quite a few as a colonial war. With the passing of the years and the moving on to third, fourth and fifth generation, a war memorial ceases to have a personal connection.

One senior heritage colleague expressed the view, “We simply cannot afford to create monuments to people who died over 100 years ago in a somewhat doubtful cause. I would much rather we used the money for good maintenance of surviving memorials.” Now that is a forthright statement that must be countered.

The case for old memorials in the modern world. In my opinion, war memorials are of contemporary relevance. They are visible heritage remnants that are and must be protected under heritage legislation. Memorials are an aspect of the unfolding and layering of history. Memorials tell the story of lives of young men lost in battle, men who died far too young and who, as their generation saw the world, made the ultimate sacrifice for their country or their people. The point of a memorial is to remind us to understand the past to bring compassion and feeling to what we see. Memorials come in all forms and why should we allow forces of destruction to triumph in eliminating heritage landmarks. If we wipe out memorials which were thought important in the past we are participating in iconoclasm. We lose touch with the people, the personalities, whose names appear on these memorials. Each one had a story; by knowing a name impressed in metal or etched in stone we are able to find out about the person. There is a greater interest than ever before in family histories and in genealogies and war memorials help us reach back into the past and to find meaning in individual stories.

Questions for the Curious. One also wants to ask some wider social questions. Why is the memorial the form and shape it is? What materials were used? Often a memorial is a work of art and so is an expression of an artist's interpretation of mood and soul. There is social significance in the symbols and forms captured in memorials; in the case of this specific memorial, the Scottish colonial roots and the military heritage of Scotland is remembered in the symbolic Iona Cross (the Celtic Cross) and in the Claymore (the Broadsword) and in the Lion Rampant cut into the stone. Even the lettering and script on a war memorial is a piece of a social history puzzle.

The Celtic Cross, Broadsword and Lion Rampant cut into the stone (The Heritage Portal)

War and a South African identity. Through this memorial one can learn a great deal about military organization and the imperialist cause and the South African nationalist cause. 1899 marked the start of a civil war in South Africa but it was also a point in time when a South African identity beyond tribe, clan and immigrant status began to be forged. A war memorial becomes a flint stone for history.

Recording the Scottish Horse Memorial. The Scottish Horse Memorial has been recorded by the City of Johannesburg and an article drawn from the inventory description written by Eric Itzkin for the City (2007) appeared on the Heritage Portal in 2015 (click here to view). The description as written by Eric Itzkin reads:

The Scottish Horse Memorial takes the form of a monumental Celtic cross, 26 feet high (7.9m), of red Scottish granite, partly rustic with (originally) bronze plaques. The base is 12 feet wide (3.6m), and surrounded by a rough cairn-like pile of quarry-dressed stones rising 6 feet (1.8m), from the ground. On the front and two sides of the cairn are inserted the plaques on which the inscription and names appear. Above the cairn rises the Cross proper resting on a pedestal consisting of a rounded hollow metal die and spreading granite plinth. On the plinth the name of the Regiment is carved in highly relieved letters and on the die above was originally a bronze casting of the Regimental crest, over which was a motto of the Order of the Thistle “Nemo me impune lacessit” and underneath “1900”. On the front of the Cross is carved a two-handed sword or claymore 10 feet long (3.0m), while at the foot of the blade is a shield bearing the Scottish Arms in relief.

The Latin motto of the Scottish Horse. (Note - Nemo me impune lacessit is a Latin motto and means “No one attacks me with impunity“. In other words that punishment will follow an attack or an offence. It was the Latin motto of the Royal Stuart dynasty of Scotland from at least the reign of James VI when it appeared on the reverse side of merk coins minted in 1578 and 1580. It is the adopted motto of the Order of the Thistle and of three Scottish regiments of the British Army.)

Whoever chose this site for a memorial Celtic Cross chose with an eye on prominence, position, mood and feeling. It is a superb view site with panoramic views of our city to the North, South and West. It is a lonely iconic Witwatersrand ridge but a place of exhilaration and mood. The wind blows the tough Highveld grass; the grass whispers of battles long ago and the souls remembered at this place speak softly. Click here to view on google maps.

A superb view site (The Heritage Portal)

A sense of place – Caledonia Hill, Kensington. The best place to park a car is in Highland Road and the memorial rises above; it is stark against a clear blue sky. The Kensington Caledonia Hill site (and even the name “Caledonia” recalls Scottish antecedents) is an inspiring place. It is a windswept, chilly, peaceful and solitary on a January sunny highveld morning. Apart from our group there is a group of open air worshippers as this place is a good one to gather and pray for the alternative small independent church groups. It is a Johannesburg moment. Members of the church group wear immaculate beautiful green and blue frock coats and one man carries a staff – I wonder if he is the bishop.

View of the memorial from Highland Road (The Heritage Portal)

Reaching the Memorial - a stairway to the Hill Top. To reach the monument one climbs a set of gently rising, wide tread steps made of Witwatersrand quartz. The stairs are in excellent condition and must have been renewed at some point.

Steps to the memorial from Highland Road (Kathy Munro)

Symbolism and meaning. On reaching the memorial the second impression (beyond the sense of place) is the heavy symbolism of the memorial. The Celtic Cross is a powerful symbol of early Christianity and dates back to the Christian missionaries of the 7th century (St Columba on Iona and St Patrick in Ireland) and was said to have absorbed the circular pagan sun symbol. The concept of the broad sword or claymore was symbolic of crusader and fighting Christianity in Europe. With a sword in battle, God was on your side. It is interesting that the idea of a broadsword on the cross predates the memorial symbols of the First World War when Reginald Blomfield incorporated the sword and hence warrior going into battle for a just cause in his Cross of Sacrifice which then became the icon unifying form in cemeteries of that war (along with Lutyens’ Stone of Remembrance). In fact the Kensington Scottish Horse memorial is architecturally path breaking because it anticipated the forms, materials, shapes and designs that marked so many First World War memorials. The Lion Rampant is a symbol from the Royal Arms of Scotland and more commonly called the Lion Rampant of Scotland. It is a symbol that was used historically by the Scottish monarchs. It is a heraldic device. The lion traditionally symbolises courage, nobility, royalty, strength, stateliness and valour, because historically it has been regarded as the "king of beasts".

The Heritage Register listing of the Scottish Horse memorial. The memorial has been listed on the Heritage Register (click here to view). However, the architect and the builder are unknown. Eric Itzkin notes that “the memorial is the same as that erected on the Esplanade of Edinburgh Castle in Scotland. The only original difference between the two being that the hollow metal die replaced the solid granite die of the Scottish memorial to facilitate transport to and erection in South Africa.” (Heritage Inventory, 2007)

No blue plaque for the Caledonial Hill memorial. There is no blue plaque on the memorial and the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation has not as yet given the memorial a heritage grading. In my opinion this has to be an “A” graded heritage site. Despite the damage it is a memorial that deserves preservation and in the past the fact that this is a memorial of stature was acknowledged by the old National Monuments Council and the South African Heritage Resources Agency with efforts made on each vandalising event to restore and repair.

The problem of vandalism. In the City of Joburg's inventory form, Eric Itzkin added some notes on vandalism:

Around 1961 the original bronze plaques and insignia were stolen and the former were replaced by granite plaques by the then National Monuments Council with financial assistance from the Transvaal Scottish Regiment. These plaques were damaged by vandals on a number of occasions subsequently and were last replaced in 2000 by the South African Heritage Resource Agency. Two of the three new plaques have since been damaged again and the broken pieces re-affixed in position by SAHRA. A section of the lightning discharge rod has also been removed which makes the memorial prone to lightening damage in view of its elevated and exposed position... Many of the steel bollards surrounding the elevated site are missing as is most of the chain joining them.

Saving the memorial plaques and local publicity for vandalism and past restoration. Isabella Pingle from the Kensington Heritage Trust informs me that the new plaques (but now damaged) were moved to the Transvaal Scottish Headquarters and Museum at The View. There has been extensive publicity about the condition and previous restorations of the memorial in the local newspaper, the Joburg East Express. Pingle has maintained an archive of all newspaper cuttings about the memorial.

The View (The Heritage Portal)

Who are the vandals and why the anger? Now as we move into 2019 the condition of the memorial raises fresh concerns and points of debate. Together with the Bezuidenhout Valley First World War Memorial it would seem that vandalism is not simply about seizing and stealing recyclable copper, brass and iron. Damage done to both memorials is provocative and perhaps even politically motivated. From the damage done it would appear to be one angry person who wishes to destroy past history; possibly someone who regards the memorial as an objectionable colonial or British imperial presence.

Context and a wider history for destruction. Historically in other societies and places, destruction of monuments, memorials, tombs, edifices happens when regime changes happen in times of war. I think of the damage to heritage sites in Iraq and Syria as regimes changed, countries were conquered and kings passed. But what is unusual about the situation in Johannesburg is that the official rainbow nation approach to political transition, meant that there has been broad understanding, incorporation of the past and no sense of victors and vanquished. We did not have a civil war. Yet It would appear that the attack happened in the dead of night; the hammer blows to the stone show great force and a deliberate violence. My surmise is that damage to memorials points to disaffection, anger, alienation by and from people who feel marginalised, disadvantaged and desperate. Perhaps extreme populist messages of destruction to the “colonial“ presence is generating a message of incitement. We are forced to acknowledge that our society is fractured and divided; we are not a homogeneous population. We talk about cultural diversity and a layering of history and a respect for past events but how can we achieve respect for memorials from people who probably do not know the history and care even less.

Damage to the memorial (Kathy Munro)

Discovering Scottish links and roots. The note in the City of Joburg's inventory form mentioned a companion memorial in Scotland and led to some online research into the Scottish Horse Memorial in Edinburgh. The Wikipedia entry mentions that: “Identical statues, in the shape of a Cross of Iona with a superimposed claymore and lion rampant in bronze and an inscription reading "Nemo me impune lacessit 1900", can be found on the esplanade at Edinburgh Castle and on Caledonia Hill, Kensington Ridge, Johannesburg.

The Scottish memorial is fully recorded as part of the National Recording Project of the The Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. A close look at this memorial fills in some of the gaps in our own memorial. It was designed in 1905 and the name S C McGlashen appears at the base on the east side. Could McGlashen have been the designer of the Johannesburg memorial too?

Scottish Horse Memorial Edinburgh (Wikipedia)

The creativity of a stone mason. McGlashen was the Edinburgh based firm of monumental sculptors founded by Stewart McGlashan (sic) (1807-73). Stewart McGlashen came from Glasgow and established his businesses in Edinburgh in the 1840s. He was listed in the Edinburgh Post Office Directories from 1847. After his death in 1873, his son Stewart (b. 2 March 1839) took over the business as S McGlashan & Son. From 1881, the spelling of the family's surname in the Edinburgh Post Office Directories is given as McGlashen. The firm produced many monuments for Glasgow and Edinburgh’s cemeteries. Most significantly “the firm was also responsible for a number of public monuments, including the Sir William Wallace Monument, Robroyston, Glasgow (1900), and the monument to the Scottish Horse (Boer War) in Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens (1905), both of which are Celtic crosses.” (click here for more details). They were also responsible for the memorials to Robert the Bruce (1889) and the Boer War in Dunfermline Abbey (1905).

In addition to the memorials mentioned above, they were responsible for a great deal of monumental stonework and many memorials in Scottish cemeteries. The details are to be found on the web source on Glasgow City of Sculpture by Gary Nisbet. The firm continued in existence until 1974. All of this information points to the likelihood that our Kensington Scottish Horse memorial was made and crafted by McGlashen and then imported to South Africa. The stone cross was made of Aberdeen granite, with that soft pink shade of stone speckled with black dots.

Discovering the Scottish Horse Regiment. Visiting the memorial led me to want to find out about who was commemorated by the Scottish Horse memorial. The Scottish Horse was a volunteer regiment raised in South Africa to fight on the side of the British. Davey writes:

The Caledonian Society of Johannesburg suggested that a corps be raised of Scots, or those of Scots descent, in South Africa. Kitchener approved and gave the command to Captain John Murray (later Lieutenant-Colonel), the Marquess of Tullibardine (who in 1917 became the 8th Duke of Atholl). The new unit was gazetted on 15 December 1900, with its depot in Johannesburg, and recruiting went ahead in Cape Town, Durban and Pietermaritzburg. Natal was an important source of enlistment and a regiment of four squadrons, 50 special scouts and 50 cyclists came into being. Recruiting was extended to Scotland and Australia with the result that a second regiment was formed. Some 3 500 men served in the Scottish Horse, the Scottish contribution from 'Home' (i.e. Britain) amounting to 1 250.

The leader of the new Regiment. 8th Duke of Atholl, also known as the Marquess of Tullibardine, John George Stewart-Murray ( 1871-1942). Son of John Stewart-Murray, 7th Duke of Atholl and Louisa Stewart-Murray and husband of Katharine Stewart-Murray (Ramsay), Duchess of Atholl, DBE). The nickname of the Marquess was Bardie and he spoke Gaelic fluently.

Hence the Scottish Horse Regiment or as they later became, regiments, were all volunteers. These were men with a spirit of adventure in support of the British cause, perhaps young men wanting to get involved in the conflict, experience the glamour of far away fights. They were men who could handle a horse and could ride. In a sense these were irregular troops, or legionnaires, not trained military men; they were horsemen probably used to hunting or frontier farm life. Some might even say mercenaries or Scots drawn from clans of the Highlands.

A useful source of information is an article by Dr A M Davey in the Military History Journal vol 6, no 3, June 1984, Scotland the Brave (click here to view). Dr Davey draws attention to the work of the Marchioness of Tullibardine (Katharine Stewart Murray nee Ramsay) on Perthshire, Scotland military records for the South African War. The Marchioness backed research into the military records of 170 officers and 1370 other ranks who served in the Black Watch and the Transvaal Scottish edited a book on the subject providing a record of photographs of many who served (the book is by Jane CC Macdonald and a reprint is available on Amazon).

Book Cover

Expanding into a second regiment. In March 1901, the Scottish Horse was expanded into two regiments: the 1st Scottish Horse and the 2nd Scottish Horse formed from 250 Australian volunteers, and drafts from Scotland and South Africa. At the end of the war in September 1902 both regiments were disbanded at Edinburgh, Scotland after repatriating the Australians and discharging the South Africans.

Casualties commemorated by the Scottish Horse Memorial. I was then curious about the number of casualties of the Scottish Horse in the South African War. The photographs taken by Derek Walker in 2007 (click here to view) on his blog site All At Sea are a great source. Even at that date he commented that the memorial was not in a very good condition and that much of the original metal work had been stolen. Walker revisited in 2012 and by that date he reported that all of the plaques and inscriptions were missing. He believed that they had been removed to prevent further vandalism and noted that the cross had recently been restored. The photographs record a total of 125 names of men including the four Zulu scouts.

The photographs taken by City of Johannesburg officials before the new plaques were moved to The View are also a good source.

New plaques (City of Johannesburg)

Emigration and occupations in the British Army. Notice all the names in Walker's photographs have a rank and a service number. The fact that this was a horse regiment is emphasized with the mention of occupations such as scouts, saddlers, a farrier, a silversmith, a vetenarian and a medical man. The names are all of British origin though by 1899 the spread of the British empire meant that British families emigrated to all parts of the empire and then were ready to enlist even if they had settled in Australia or Canada. The mention of the Zulu scouts (4 casualties) is significant as these men would have had a valued role to play in reconnaissance.

Names documented too on the Edinburgh Scottish Horse Memorial. Another source of information on the casualties of the Scottish Horse in the South African War are the names that are recorded on the Scottish Horse (South African) memorial at Edinburgh Castle. These names have been recorded and transcribed by Annie Capewell (click here to view). It is the same list of men as appear on the Kensington memorial.

More about men whose names appear on the memorial. Reading through the names of men who died in the war led me to drill down into the archives to perhaps try to find out about at least one soldier whose name appears on the Scottish Horse Memorial. For example, here is the record of Major Frederick Dymoke Murray, of the Scottish Horse, and of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders) retrieved from AngloBoerWar.com.

Major Frederick Dymoke Murray, of the Scottish Horse, and of the Black Watch (Royal Highlanders), was born on April 28th, 1872, and entered the Royal Highlanders on December 5th, 1891, in which regiment he received his lieutenancy on July 29th, 1896. From August 1st, 1898, till October 8th, 1899, he was aide-de-camp to the Hon. Sir Walter Francis Hely-Hutchinson, G.C.M.G., the late Governor and Commander-in-Chief in Natal; in October was aide-de-camp to the Lieutenant-General commanding a division, and from December 1st, 1899, till September 24th, 1900, was a signalling officer of a mounted Brigade of the Natal Field Force, graded as a staff captain. He was also again an aide-de-camp to the Governor and Commander-in-Chief in Natal, and during the earlier portion of the war was also acting brigade major to an infantry brigade. (Nottingham Evening Post, Monday 4th November 1901)

Major Frederick Dymoke Murray, one of the killed, belonged to the Black Watch, but was commanding the 2d Regiment of Scottish Horse. He was in his 30th year. His services in the present campaign had been twice mentioned in despatches by Sir Redvers Buller. He joined the Black Watch ten years ago. (Edinburgh Evening News, Monday 4th November 1901)

F D Murray, then commanding the 2nd Regiment of the Scottish Horse, was killed in action on on 30th October 1901. There is a memorial in Christ Church, Epsom, Surrey (his connection with Epsom is that from 1878 his parents and their children lived at Woodcote Hall, South Street, Epsom). He's also remembered on the Eton College memorial, the Black Watch memorial in Perth, Scotland, and the Black Watch memorial in Edinburgh.

Bravery in Action. The Victoria Cross was awarded to Lieutenant William John English for his heroic actions while serving with the Scottish Horse. Lt English (later Lt Col) was awarded the Victoria Cross for his heroism on 3 July 1901 in South Africa whilst serving as a lieutenant in the 2nd Scottish Horse. He is one of very few Irish born recipients of the Victoria Cross. The citation read: “This officer, with five men, was holding the position at Vlakfontein on 3 July 1901 during an attack by the Boers. Two of his men were killed and two wounded, but the position was still held, largely owing to the lieutenant's personal pluck. When the ammunition ran short, he went over to the next party and obtained more; to do so he had to cross some 15 yards of open ground, under a heavy fire at a range of from 20 to 30 yards.”

English received the Victoria Cross in person from King Edward VII in July 1901. He later achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He saw action in three major wars (the South African War, World War One and World War Two) and died on active service in 1941 (details summarised from the entry on Wikipedia).

Lt William John English

War Horses in the South African War. Since the Scottish Horse memorial commemorates a cavalry regiment, I wondered about the role of the war horse in the South African War. The horse too should be remembered when visiting this memorial. Horses played a vital role in intelligence work, scouting and pulling gun carriages in battle to achieve swift movement. The subject of horses in the war has been well researched and a good selection of articles can be found online. The high demand for war horses meant that large numbers were imported to South Africa by the British from all parts of the world, including 50 000 from the United States and 35 000 from Australia – most of them landing in Port Elizabeth. A variety of breeds of horses were used during the war, including English Chargers and Hunters from England and Ireland as well as Australian Walers bred, ironically, from an original shipment of Cape Horses in the 1700s. Click here for more information.

The author of the article in the link above makes the point that the lifespan of the horse was likely to be no more than six weeks from time of arrival at the port to death. It is estimated that "The number of horses killed in the Anglo-Boer War was unprecedented. When one considers that over 300 000 of them died during active service - not counting the horses on the Boer side – one can begin to appreciate how important these animals were in that conflict.”

Later link to the Transvaal Scottish. After the war, the Scottish Horse was disbanded and in its place, the Transvaal Scottish regiment was founded in 1902. This regiment served with honour in all wars South Africa has participated in in the 20th century. Its regimental headquarters is The View, a landmark Parktown mansion.

A future for this memorial and a way forward. Should this memorial again be restored or can the memorial not be rededicated to capture a wider history and legacy? Should this memorial be moved? One suggestion has been to remove the Celtic Cross to Braamfontein Cemetery. The Celtic Cross still has meaning for people who worship on the hill. I think the memorial needs a context and could be part of an educational centre about the South African War. Possibly attach such an educational centre to the nearby Jeppe Boys High School. Could a plinth be added to acknowledge the deaths in the war of all who died? Should we not be forming an action committee made up of city officials, heritage enthusiasts, local worshippers, representatives from the Transvaal Scottish, officials from SAHRA?

A student group visits the site in 2018 (The Heritage Portal)

Another idea is to make this a Johannesburg heritage and tourist Site. Bring back the names of the men and research and tell their story. There could be a focus on genealogical history. We need a centre that explains the history of imperialism and colonialism against the backdrop of the history of war and its impact. How did war affect the layering of South African history in the 20th century and beyond? Ideas from the community are welcome.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters and is well known for her magnificent book reviews. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.