Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Every loved domestic dog, no matter how humble their origin, remains the best dog in the world in the eyes of their masters.

We affectionately refer to dogs as our best friend. They also happen to be humankind's oldest "friend" in the animal kingdom in that Canis familiaris, the domestic dog, was the first animal species to be domesticated by humans.

The South African produced photographs included in this article span a 40-year period (1875 to 1915), more or less the same period that witnessed the unfolding of the majority of today’s established dog breeds.

The photographs included, plus any other existing photographs of this era that may not have been uncovered to date, are also a valuable source in assisting scientists and researchers conducting research on modern dog breeds.

Photographed - South African domestic dogs in front of the lens

The stereotype of the exceedingly serious sitter staring stiffly at the studio camera during Victorian and Edwardian time belies the fact that our ancestors also loved and cared for their dogs with the same passion as most of us do today. The images included provide evidence of these familial and emotional attachments to their dogs.

Since the commercialisation of photography in South Africa (largely early 1860s onwards), man’s best friends have also been allowed into some South African photographic studios. Not all photographers at the time would however have endorsed having dogs in their studios.

Photographing dogs (and children) was not an easy task at the time due to the longer exposure times required. Where a dog (or a child) moved during the required exposure time, the photographer would then have to reshoot or simply provide an image with ghost like appearances of either dog or child.

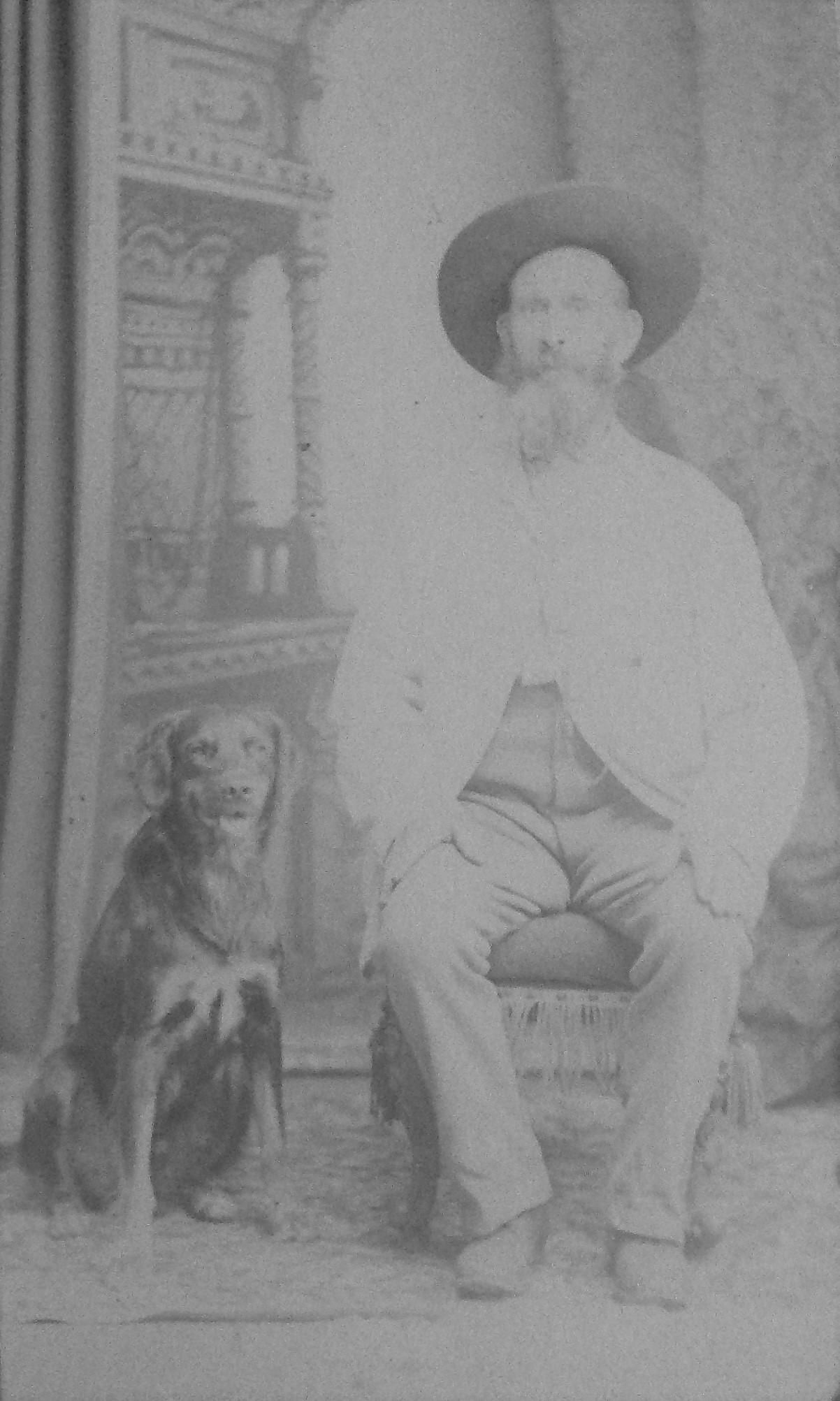

Unknown soldiers and his obedient dog. Cabinet card format photograph scanned from original glass negative by Graaf-Reinet based photographer William Roe. The dog is slightly blurred due to movement during the exposure time. Another image of the same two in a different pose exists in the Graaff-Reinet Museum photographic collection

Not one, but two. Unknown man with his two pet dogs. The dog on top of the fake rock is slightly blurred due to the dog moving during the exposure time. The fox terrier has a name tag/licence disk on the collar around his neck with bells attached. Cabinet format photograph by Johannesburg based photographers Davies brothers – Circa 1896

Jacobus Kok from the Reitz district with the family dog. The photograph confirms how difficult it was to photograph children and animals in the earlier years of photography in that both dog and child show some blur. Note the dress. It was not uncommon for little boys to wear dresses during the Victorian era. Cabinet format photograph by Bethlehem based photographers Ribnick & Segal – Circa 1896

My best friend. The dog’s head is slightly blurred due to movement during the photographic exposure time. Cabinet format photograph by East London based photographer Willard Jakins – Circa 1900

Let me rather hide. Unknown couple. Cabinet format photograph by Winburg (Orange Free State) based photographer George Perry – Circa 1902. The dog was shaking its head during the photographic exposure time – therefore the blurred appearance of its head

Unknown child with pet dog. The head of the dog is slightly blurred due to movement during the photographic exposure time. Cabinet format photograph by Kimberley based photographer Selkirk – Circa 1895

Some professional photographers made a point of inviting sitters and their pets into their studios – some more so than others. One South African photographer who stands out as a “dog photographer” was Port Elizabeth based James Edward Bruton. He not only took photographs of dogs with their masters but was also happy to capture images of dogs only – as can be seen in two of the images included in this article. Other prominent 19th century South African photographers that were clearly comfortable with dogs being present in their studios include Graaff-Reinet based William Roe and Son as well as Cape Town based Samuel Baylis Barnard.

My name is Hottentot – Don’t you mess with me. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Port Elizabeth based photographer James Edward Bruton – Circa 1878. Inscription on the back states that the image was spoiled due to Hottentot wagging his tale.

Ugly! Me? Never. I’m a pedigree. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Port Elizabeth based photographer James Edward Bruton – Circa 1878

Three unknown brothers with their pet dog. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Worcester based photographer JD de Villiers de Wit – Circa 1874.

Let’s both look at the camera. Could this be a staffy? Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Port Elizabeth based photographer James Edward Bruton – Circa 1878. The dark patch on the right hand side of the image indicates that the glass plate on which the image was produced was damaged prior to the paper version being produced.

As camera equipment became less unwieldly and more portable, some photographers were also willing to travel in search of new business resulting in pets and farm animals, ranging from dogs to horses, donkeys, sheep, goats and occasionally a cat being spotted on early South African carte-de-visite or cabinet card format photographs.

The photographs themselves show some disciplined dogs sitting patiently, whilst other are clearly not in awe with the photographer or the owner’s instructions and demands.

Dog breeds have evolved. Although some of the dogs that appear on the photographs included may visually correspond with some breeds known to us today, they cannot be placed in distinct breed categories. At the risk of getting it wrong, the author therefore did not attempt to identify all the breeds of dogs photographically captured.

All the images included in this article were produced by professional photographers, mainly captured in their studios but not to the exclusion of the occasional image captured outdoors. Photographic technology for the amateur photographer to capture images easily and inexpensively, only started developing from 1900s onwards.

Two brothers outside a mining compound posing with their own dogs or would these be compound dogs? Cabinet format photograph by Johannesburg based photographers Pollard and Zadik – Circa 1904

A rather scruffy looking St. Bernard described on the back of the image as a 1902 champion. By unknown photographer.

Domesticated dogs during Victorian times

Attracting criticism from the elite and aristocracy, keeping of pets was frowned upon until the 19th century. The Victorians were ultimately responsible for the changing attitudes towards domestic animals which resulted in pet keeping becoming culturally more acceptable. Writers and artists in the 19th century assigned a new “moral value” to pets, and consequently saw keeping them as beneficial for children. Dogs in the house taught children to be caring and responsible. Pets were also thought to enhance the domesticity of a home (Ferguson, 2019).

Pedigree dog breeding therefore largely started during the Victorian era. Dog breeds from a century ago are vastly different to their contemporary counterparts. Sadly, in some instances, refined breeding has resulted in severe health related issues for selected breeds.

The emotional attachment Victorians had for their pets, and the role of pets in family life, has been largely ignored by historians in the past. As pets became integrated into family life, contemporary publications and handwritten diaries confirm just how attached the Victorians were to their pets. The keeping of pets certainly triggered a new form of consumerism at the time.

We are friends. Cabinet format photograph by Clanwilliam based photographer JB Belgrove – Circa 1903

Unknown girl with her Fox Terrier friend. Cabinet format photograph by Queenstown based photographer Lesley Wagstaff Ford – Circa 1902

Brief history of the dog

The history of dogs remains as intricate as that of the people they lived alongside, lending support to the long depth of the partnership.

To appreciate the domestication history of the dog, a reflection on the world view is necessary before considering the African continent or southern African history.

World history

The history of dog domestication confirms the ancient partnership between dogs and humans. That partnership was likely originally based on a human need for help with herding and hunting, for an early alarm system, and for a source of food in addition to the companionship many of us today know and love. In return, dogs received companionship, protection, shelter, and a reliable food source. But when this partnership first occurred remains a fascinating ongoing debate amongst scientist.

An over simplified view is that it was once thought that some visionary hunter-gatherers nabbed wolf puppies from their den and started raising wolves which became tamer over time, resulting in the first steps on the long road to leashes, dog training schools and veterinary bills. The essence of this thinking is that humans actively bred wolves to become dogs just the way they now breed dogs to be tiny or large or to herd sheep. The prevailing scientific opinion today is however that this origin story does not hold water in that wolves are hard to tame, even as puppies. Many researchers actually find it much more plausible that dogs, in effect, invented themselves.

To date, the earliest confirmed existence of domesticated dogs was obtained from a burial site in Germany at Bonn-Oberkassel, which has joint human and dog interments dated to 14 000 years ago.

At a high level, scientists suggest that wolves and dogs split into different species around 100,000 years ago. Although analysis has shed some light on the domestication events which may have occurred between 40,000 and 20,000 years ago, researchers are not all in agreement with such view.

Some researchers suggest that wolves were domesticated around 10,000 years ago, while others suggest 30,000 years ago. Some claim it happened in Europe, others in the Middle East, or East Asia. Others again argue wolves domesticated themselves, by scavenging the carcasses left by human hunters, or loitering around campfires, growing tamer with each generation until they became permanent companions.

Origin theories around the dog therefore remain complicated, in that some researchers further suggest that there were two events around the domestications of dogs, 2500 years apart. It is suggested that the first species to be domesticated by humans, at least 15 000 years ago, was the Eurasian grey wolves. Strong evidence exists that the domesticated dog originated in Central Asia, around modern-day Nepal and Mongolia.

According to Professor Larson from Oxford University - Many thousands of years ago, somewhere in western Eurasia, humans domesticated grey wolves. The same thing happened independently, far away in the east resulting in two distinct and geographically separated groups of dogs. Around the Bronze Age, some of the Eastern dogs migrated westward alongside their human partners. Along their travels, these migrant Eastern dogs encountered the indigenous Western dogs, mated with them, and effectively replaced them.

Regardless of the exact dates that scientists are grappling with, Larson succinctly summarises that dogs have developed over thousands of years, have mated with each other, cross-bred with wolves, travelled over the world and have been deliberately bred by humans. The resulting ebb and flow of genes has turned their history into a muddy, impure mess—a homogeneous soup, keeping in mind that purebreds are not genetically very diverse. As difficult as it may seem to imagine, a Chihuahua and a St. Bernard are still the same species.

Scholars now agree that most of the dog breeds we see today are recent developments. The oldest modern dog breeds are no more than 500 years old, whilst most only date from less than 150 years ago.

Unbeknown to us, the majority of dogs, along with their genetic diversity, fall in the group of "village dogs", a much larger group of free-roaming and breeding populations which have much older lineages than the pure breeds.

Although an estimated 400 man-made dog breeds exist today, primitive dogs - those that have undergone little artificial selection - still occur, especially in the tropics. The most famous being the Australian the dingo.

She is not heavy, she is my friend. Unknown child sitting on her Labrador looking pet dog. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Graaff-Reinet based photographer William Roe – Circa early 1880s

Proud owner - unknown child with beautiful long-haired pet dog on a leash - Cabinet format photograph by Graaff-Reinet based photographers William Roe and Son – Circa 1895

African and southern African history around the dog

The first distinct and distinguishable dog “breeds” in North Africa date back to 3000 to 4000 BC. Egyptian tomb paintings from 2000 BC indicate that there was evidence of at least four dog breeds being in existence at the time (van Sitter & Swart, 2003).

Dog skeletal remains suggest the presence of dogs on several Iron Age and a few Stone Age sites in southern Africa. The earliest conclusive evidence of such dates to 570 AD. San rock paintings also confirm the importance of dogs in their society at the time.

Africanis is an umbrella name for all the aboriginal dogs in Southern Africa. It is believed to be of ancient origin, directly descended from hounds and pariah dogs of ancient Africa, introduced into the Nile Valley from the historic Levant (area in the middle east).

The first recorded reference to indigenous dogs in southern Africa was by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1497, who noted of a San community at St Helena Bay: “They have many dogs like those in Portugal, which bark as do these”. Between 1700 and 1800, explorers of the interior recorded dogs amongst various indigenous groups. Reports tended to focus on the dogs small and unattractive appearance, and their courage and usefulness at hunting. At least two early ethnographers also provided descriptions of the various indigenous dogs and their social roles. Both these ethnographers feared that these dogs were threatened with extinction (van Sittert & Swart, 2003).

Today’s South African dog population has its origin from two distinctly separate streams, namely the dog race that developed on the African continent and the dog races that were brought into South Africa by European settlers from the mid-17th century onwards.

Van Sittert and Swart (2003) state that each epoch of human-canine interaction in southern Africa produced its own peculiar animal resulting in their classification literally into a pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial dog. Falling into both the colonial and post-colonial categories, a middle-class dog fancy boomed in South Africa towards the last quarter of the 19th century characterised by the importation of British standards.

You stand and I get the chair – Smile. Cabinet format photograph taken outdoors (in front of corrugated house) by photographer R Albert Smith – Town unknown – Circa 1905

Miss G Paynter with her little mongrel. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Simonstown based photographer Charles Boon – Circa 1878. Note the young lady smiling. Due to longer photographic exposure times it was unusual to find a sitter smiling for the camera pre 1880s

They think it is funny – I don’t. A very unhappy looking dog “bursting” its head through a piece of paper. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Ficksburg based photographers Barraud Brothers – Circa 1882

Unknown man and his obliging companion. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Bloemfontein based photographer Francis Armstrong – Circa 1878.

Consequences of dog domestication

In studying the images included, it is clear that most sitters were affectionate towards their pet dogs, whilst to some, like today, the dog was simply viewed as an animal to “own”, with little if any affiliation shown towards the animal.

This gave rise to the establishment of the SPCA which was founded in Cape Town as early as 1872, sadly confirming that pet owners, in this instance dog owners, did not always treat dogs as their best friend.

Cruelty to animals is sadly also as old as human’s need to domesticate pets, resulting in the South African urban middle class having to align to standards around prevention of animal cruelty in that cruelty against animals was made a criminal offence in the Cape as early as 1856, Natal (1874), the Orange Free State (1876) followed by the South African Republic (1888).

For many a years’, owning a dog came at a cost in that government entities generated an income by collecting taxes on each dog owned. An initial attempt was made at checking the growth of the rural canine population through taxation in that dog tax was passed in Natal as early as 1875 followed by the Cape (1884), Orange Free State (1891) and finally the South African Republic (1892).

Wait – I’m distracted – I’ve got sniff in the nose - Three unknown men with short-haired dog. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Port Elizabeth based photographer James Edward Bruton – Circa 1876

Rykie van der Bijl (without hat) and friend (slightly out of focus – eyes and mouth pencilled in by photographer). Notice the dog’s crossed legs. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Cape Town based photographer F Hodgson – Circa 1885.

Patch-eye. Man’s best friend. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by unknown photographer. Circa 1908.

Sit! Unknown man and his dog. Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Port Elizabeth based photographer Robert Harris – Circa 1878. Image electronically manipulated due to poor quality of original image.

What would the two be looking at? Carte-de-Viste format photograph by Cape Town based photographer Johann Heinrich Kaupper – Circa 1878.

The Shaw family (J.M., Maud, Violet & Alf) with their Maltese looking dog named Frisk. Cabinet format photograph by Cape Town (Woodstock) based photographer RW Vince – Photograph taken during 1898

List of early South African photographer’s photographs presented in this article:

- Armstrong F – Bloemfontein

- Barnard Samuel Baylis – Cape Town

- Barraud Brothers – Ficksburg

- Belgrove JB – Clanwilliam

- Boon Charles – Simonstown

- Bruton James Edward – Port Elizabeth

- Church Fred – Lady Grey/Aliwal North

- Davies Brothers – Johannesburg

- De Villiers JP – Parijs

- De Villiers de Wit – Worcester

- Ford Leslie Wagstaff – Queenstown

- Goch James Frederick – Johannesburg

- Harris Robert – Port Elizabeth

- Hodgson F – Cape Town

- Jakins Willard – East London

- Kaupper JH – Cape Town

- Perry George – Winburg

- Pollard & Zadik – Johannesburg

- Ribnick & Segal – Bethlehem

- Roe William (and son) – Graaff-Reinet

- Selkirk – Kimberley

- Smith R Albert – Unknown location

- Vince RW – Cape Town (Woodstock)

Unknown man with his dog. Carte-de-Visite format photograph by Cape Town based photographer Samuel Baylis Barnard – Circa 1876. Barnard emphasised the man’s eyes on the original photographic glass plate before producing the paper based image. The dog seems to have a name tag/licence disk attached to the leather collar around its neck

Dolly Adlam with her lapdog – a Maltese poodle. Cabinet format photograph by Johannesburg based photographer James Frederick Goch – Circa 1896

Bezuidenhout brothers with their loyal little friend. Cabinet format photograph by Parijs (Orange Free State) based photographer JP de Villiers – Circa 1898. The photograph was clearly taken outside their place of residence – Note the makeshift backdrop as well as the black mourning band on the jacket of one of the brothers

I feel rejected. You have already replaced me. Unknown couple with baby. Cabinet format photograph by Lady Grey/Aliwal North based photographer Fred Church – Circa 1899

Main image: Miss Gibson with her dog. A rather unusual composition for those years in that Carte-de-Viste format photographs were not commonly produced in a horizontal format. Photograph by Cape Town based photographer Samuel Baylis Barnard – Circa 1880s. Barnard emphasised Miss Gibson’s eyes on the original photographic glass plate before producing the paper based image

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Ferguson, D. (2019, 19 October). How Victorians turned mere beasts into man’s best friends. (theguardian.com)

- Gibson, N. (2020 – 16 April). Dog breeds from 100 years ago. (ranker.com)

- Gorman, J. (2016). The big search to find out where dogs come from (www.nytimes.com) – Extracted 26 April 2020

- Hardijzer Photographic Research Collection. All photographs contained in this article originate from this collection

- Hirst, K. (2019 – extracted 26 April 2020). Dog History: How and why dogs were domesticated (www.thoughtco.com)

- Larson, G. (2016). Dogs were domesticated, not once but twice…in different parts of the world. (www.ox.ac.uk/news)

- Long, D. (2007). The best dog in the world. Vintage portraits of children and their dogs. Ten speed press. Toronto

- Milliken, G. (2015 – Extracted 20 April 2020). The first dogs may have been domesticated in Central Asia (www.popsci.com)

- Van Sittert, L. & Swart, S (2003). Canis Familiaris: A dog history of South Africa. South African Historical Journal 48 (1). 138 – 173

- Wikipedia.org (Africanis) – Extracted 26 April 2020

- Yong, E. (2016 – Extracted 26 April 2020). A new origin story for dogs. (www.theatlantic.com/science)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.