Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, journalist Lucille Davie uncovers some of the powerful and painful history of Sophiatown. She highlights the origins of the suburb, its vibrant cultural scene and the tragedy of the forced removals. The piece was originally published on the City of Joburg's website on 20 March 2003.

Since June 2000 more than R21-million in land compensation claims has been paid out to ex-Sophiatown residents. This adds up to 544 claims of R40 000 each.

The payments, considered by the national Land Affairs Department to be “restitution awards”, were paid as a “gesture of reconciliation” for the loss of homes and indignity suffered by residents at the time of removals.

The Department’s unofficial tally of R21 760 000 has been paid for Sophiatown and the small neighbouring suburb of Martindale (now a light industrial area).

The Department arrived at the figure of R40 000 as an estimate of the current average value of a stand in present-day Sophiatown, estimated by an estate agent in the area to be around R50 000-R60 000. Stands with houses sell for around R200 000 nowadays.

Sophiatown, renamed Triomf in the 1960s, was a lively, mostly-black suburb that was cleared and flattened by the end of 1963 by the apartheid government.

Former Sophiatown residents are not happy with the R40 000 payment. Charlotte Girlie Malikaf, who died a month ago at 92, received this amount for her stand at 54 Edward Road.

Her granddaughter Yolande Frederick was not impressed with the amount paid out or the process of arriving at the final figure. She was on a committee formed to liaise with ex-Sophiatown residents regarding land claims. She says they were consulted up until the final decision on the amount to be paid was made, from which they were excluded. She comments: “The whole thing stank. I was very, very upset that we were not finally consulted.”

Frederick says that she was expecting to be paid at least R70 000. “I understand that compensation could not be 100% of its present value. We were told to take it or leave it.”

And what did her grandmother do with the money? “She didn’t say anything for a week. Then she asked us what she could do with the money,” recounts Frederick. Malikaf owed R23 000 rent on her Eldorado Park home, as well as R9 000 for water and lights. She paid these amounts, and was left with R8 000.

Frederick says they took her on holiday to East London with the remainder. Frederick concludes: “We are grateful to have had the money.”

Seventy-nine year old David Pooe, who hasn’t received his compensation payment yet, feels that the properties are worth far more than R40 000. “The properties are worth a minimum of R100 000,” he says. His family owned several properties in Sophiatown.

”In the 1950s when we were threatened with removal, we took the matter to court but we lost the case. We fought it on the basis of freehold rights,” says Pooe. He maintains that his family lost the case because the “judge, prosecutor and defence attorney were white”.

The case went on appeal, then back to the Native Resettlement Board. “My sister wept in court,” says Pooe. But Pooe’s mother was offered a house in Diepkloof in lieu of compensation.

Pooe is optimistic that he will get what he believes to be the true value of the plot – at least R100 000. “People are getting R40 000 for properties that are worth something in the six figure range,” he says with a wry smile.

Removals

Sophiatown’s cosmopolitan community was finally forcefully removed in 1963, in a process of relocation that begun in 1955. Once all the closely-packed houses were demolished, a new white lower middle class suburb, Triomf (Afrikaans for “triumph”), was laid out, occupied by mostly Afrikaans speaking residents.

These days it consists of a mishmash of unimaginative houses on small plots, with dull-grey precast concrete walls enclosing them, and full-windowed burglar guards shutting them off further. The suburb is overshadowed by the ugly 15-storey police flats on the Westdene ridge, an unattractive landmark visible kilometres away. In the middle of the suburb is a half moon of shops, collectively called the Triomf Shopping Centre.

There’s an irony to this – Sophiatown was originally planned as a suburb for whites but it was only in the 1960s, after the cruel upheaval of a poor but vibrant mostly-black community, that it became an exclusively white suburb.

Christ the King Anglican Church in Ray Street was one of the few structures that survived (Lucille Davie)

Origins

In 1897 Hermann Tobiansky purchased a portion of land of the farm Waterval that became Sophiatown. Some eight kilometres from the city centre, in those days a far-away suburb, Sophiatown had no transport links to the city. According to researcher and chief librarian Anna Smith in Johannesburg Street Names, the suburb was originally called Sophia, after Tobiansky’s wife, but after 1919 it became known as Sophiatown, and dubbed later by its residents as “Kofifi”, a slang Afrikaans word, the meaning of which is unknown.

Tobiansky named the streets after his children – Gerty, Bertha, Toby, Edith and Sol. By 1904 Sophiatown had been surveyed, and Tobiansky placed an advert in The Star on 5 February.

It was geared at the working class and read:

“SOPHIA TOWN IS FREEHOLD

SOPHIA TOWN STANDS are within reach of the means of one and all.

SOPHIA TOWN is near “Brixton” and “Auckland Park”.

SOPHIA TOWN is an easy thirty minutes ride on bicycle.

SOPHIA TOWN is only 4 miles from the Market Square.

SOPHIA STANDS are 100 X 50 ft, freehold, no stand rent.

SOPHIA TOWN has good soil and magnificent view sites.

SOPHIA TOWN has an abundance of water.

SOPHIA TOWN gives the working man the chance of securing his own freehold at a low figure within 10 minutes of a good railway service.

SOPHIA TOWN is only 10 minutes walk from Claremont Railway Station.”

The ad went on to explain that terms of payment consisted of “£10 down, balance in 3, 6, 9 months, WITHOUT INTEREST or the purchaser can pay cash and get a discount of 5 per cent”.

Whites started buying properties in the suburb, but soon blacks and coloureds bought properties too. This was probably allowed to happen because the suburb was relatively far from the city centre, and the city council had its hands full coping with overcrowding and slum conditions in the city.

Before the 1913 Land Act, blacks had freehold rights, and they bought properties in Sophiatown as well as Alexandra, a township north west of Johannesburg. After 1913 blacks had their freehold rights taken away. The immediate effect of the Act was to empty the countryside of black people as their small holdings were removed from them, putting more strain on already inadequate housing in the cities.

In 1897 a sewage farm had been established across the road from Sophiatown, in present day Westbury, according to George Grant & Taffy Flinn in Watershed Town. By 1907 this farm was closed and moved to Klipspruit, in present-day Soweto (it’s been subsequently moved). Westbury and surrounding suburbs like Newclare and Claremont started being settled, mostly by coloured residents, and Sophiatown became less desirable as a suburb for whites, and they started moving out.

By the 1920s most whites had moved out of the suburb, and it became a cosmopolitan mix of blacks, coloureds, Indians and Chinese, with a mix of languages. Now, speaking to ex-Sophiatown residents almost 50 years later, they switch easily between English and slang Afrikaans and an African language.

Sophiatown started out as rows of neat semi-detached and free standing houses with small yards. As the waves of migration from the countryside progressed and the demand for labour rose with rapid industrialisation through the 1920s and 30s, people joined relatives in these small dwellings.

Tin shacks went up in the backyards, until there were up to 40 people living in the backyards, using one tap and an outside toilet in the yard. In cases backyard coal sheds were used to house a family. The main house had families living in each room.

Ghetto

The suburb’s facilities simply couldn’t cope and by the 1940s Sophiatown was a ghetto. A visiting clergyman wrote a short article in The Saturday Star of January 1924. He described Meyer Street: “The beginning of the street is ordinary enough, running up hill for 300 yards, with tarmac and footpaths and gutters. After that there are no footpaths, no gutters, no tarmac and the houses are innocent of waterborne sewage.”

Sophiatown had two cinemas (the classy Odin in Good Street and the not-so-classy Balansky’s in Main Road), a swimming bath (in Meyer Street), a clinic and a crèche, several churches, a number of shebeens, several schools and shops, but no open spaces, no library, no sporting facilities, no restaurants.

Together with surrounding suburbs known collectively as Native Western Township, it was simply a labour pool for the growing industries of Johannesburg, and when, after WW2, the country experienced a depression, the half-hearted resolutions to remove the residents of Sophiatown and flatten the suburb throughout the 1930s and 1940s, were finally acted upon.

Culture, gangs and shebeens

It was a unique womb of creativity. It nurtured an extraordinary band of writers, most of whom got in touch with their talent by writing for Drum magazine. Among this group was Bloke Modisane, Todd Matshikiza, Nat Nakasa, Lewis Nkosi, Eskia Mphahlele and Can Themba.

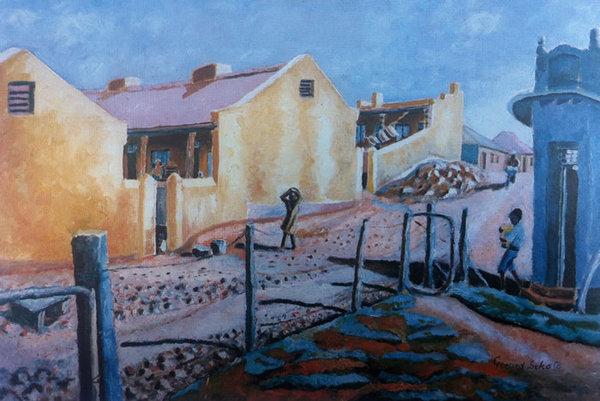

Artist Gerard Sekoto, who lived in Sophiatown for several years, captured the streets of Sophiatown in rich colours and textures, in Yellow houses, a street in Sophiatown, and Looking down the Hill, Sophiatown. He went into exile in 1947 and Clive Chipkin in Johannesburg style, architecture & society, writes that he “never again paints with the same intense relationship to the life around him”.

Yellow Houses, a street in Sophiatown 1940 (WikiArt)

In a clear rejection of white apartheid society, residents of Sophiatown embraced American culture, most obvious in the movies that showed in the cinemas in the suburb. Their dress reflected the fashion styles of the 1950s: the men wore double-breasted suits, flashy black and white shoes, and soft felt hats placed at a strategic angle. The women wore gathered skirts with narrow waists, pumps, and gloves in the evening.

Jazz took off, and a number of bands were born in Sophiatown, including The Harlem Swingsters, The African Inkspots, and The Jazz Epistles, whose members included Dollar Brand, Kippie Moeketsi and Hugh Masekela. Blues singer Dolly Rathebe was a huge hit in Sophiatown by the end of the 1940s.

As in any ghetto, gangsters emerged, taking on titles like the “Americans”, the “Russians”, and the “Vultures”. The streets of Sophiatown saw fierce fighting, with many young men dying by the knife or gun.

Because of laws prohibiting blacks from buying liquor, shebeens sprang up, the most famous being 39 Steps in Good Street, owned and run by Fatty Phyllis Petersen, known as Fatty 39 Steps. It was housed on the upper story of a two-storey house. It was finally dismantled and demolished in 1958.

One of Sophiatown’s most famous residents was the late Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, fierce anti-apartheid campaigner and friend of everyone in Sophiatown, especially the children. He lived in the suburb for half of his 12 years in Johannesburg, and when he was recalled to England in 1955 he said in his autobiography Naught for your comfort: "I am in the process of dying." He never really got over his love affair with the suburb and its people, and for the rest of his life he longed to come back to South Africa. He indicated that he wanted to be buried in Sophiatown, and when he died in 1998, his ashes were brought back to Sophiatown where they lie beneath several large granite slabs behind the church.

Book Cover

Surrounding suburbs

Whites were rapidly filling up the surrounding suburbs of Westdene and Auckland Park, and the council was under further pressure to remove this “black spot”. On the morning of 10 February 1955, 2 000 police officers armed with machine guns, rifles and knobkerries moved in, and residents woke to bulldozers at their front doors.

Sophiatown residents were removed to Meadowlands, in present day Soweto, where rows of small box houses had been built in the veld; no streets or street lights, no pavements, no fences demarcating their yards, no trees to shelter from the sun and rain, and most important . . . no community.

After the relocations and demolition all that remained of Sophiatown was the street layout, the street names, the Christ the King Anglican Church in Ray Street, past ANC president Dr Alfred Bitini Xuma’s house in 85 Toby Street (now 73 Toby Street), and another house in Toby Street. The swimming pool had been filled in, and Huddleston’s rectory was demolished – all that remains of it are several slabs of concrete in the grounds of the Anglican Church.

Xuma moved to Dube in 1959. His simple but attractive bay windowed house in Sophiatown still exists, much the same as it was in 1934 when it was built for him, except it now has a high wall surrounding it. It recently sold for around R400 000, because it’s now a national monument.

Alfred Bitini Xuma’s house (The Heritage Portal)

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.