Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

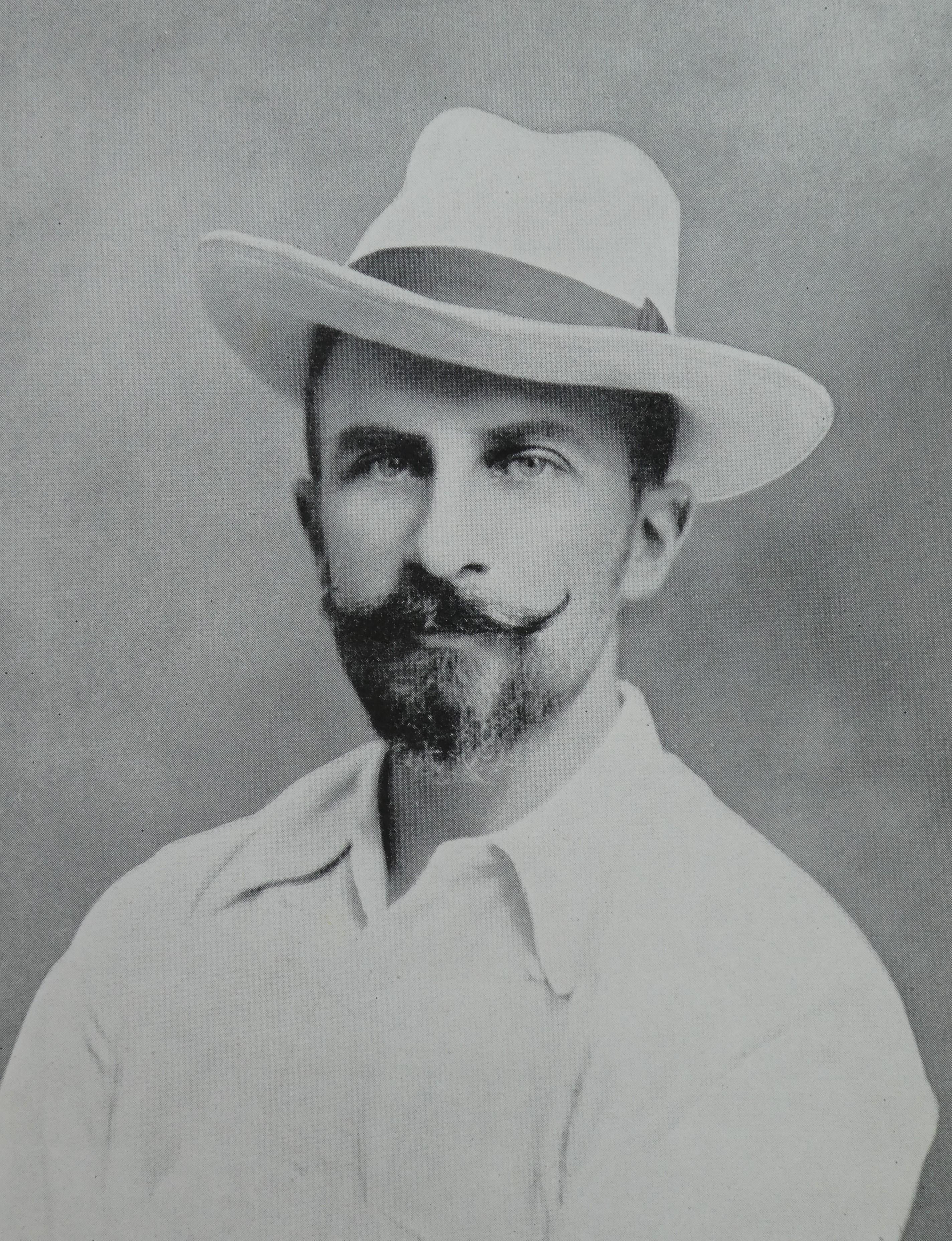

James Stevenson-Hamilton (1867-1957) is familiar to most South Africans as a naturalist and game conservationist. A Scottish cavalry officer, whose regiment fought in the South African War, in 1902 he was appointed Warden of the Sabi Game Reserve, later to become the Kruger National Park. He remained there until his retirement in 1946. What is less well known, however, is that before joining the Transvaal civil service, he had already spent some time in South Africa, had an important military career behind him, and had contributed to European knowledge of the African continent by his largely self-financed visit to Barotseland under the aegis of the Royal Geographical Society in 1898-1899. Stevenson-Hamilton had another virtue – he was an inveterate diarist and recorder of his experiences. Clever, educated, perceptive, and observant, with a well-developed sense of humour, his writings are of great interest. The following is a lively account of a visit he made to Johannesburg in the winter of 1889. The account is enhanced by his own contemporary sketches that form part of his diary. The text has been lightly edited by Jane Carruthers, who is grateful to the Stevenson-Hamilton family for allowing her access to their records.

Originally published in Africana Notes and News 27(3), September 1986, pp.93-104

Portrait of James Stevenson-Hamilton

I was serving as a very young subaltern in the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons, which had been stationed in Natal since 1881. The regiment had just come back to Maritzburg after two years in Zululand in connection with the Dinizulu rebellion there, and we were all highly excited about the Golden City where the big boom was at its height, the repercussions of which had stirred even sleepy Maritzburg to its depth.

My delight may therefore be imagined when Captains [Michael} Rimington and [J. Watkins] Yardley of the regiment, who had obtained leave of absence to attend the Johannesburg Winter Handicap, asked me to accompany them on the expedition. The necessary permission was quickly sought and, after some slight demur, granted, greatly to my own joy and the envy of my brother subalterns.

In those days, although the line was laid for some distance beyond it, the official railhead was Ladysmith and at that point passengers, at any rate for the Free State route to the Rand, had to disembark and join the stage coach.

Accordingly, on our arrival in the early hours of the 21st June, we found the mail coach drawn by eight horses waiting outside the station, and punctually at 8 a.m. we set off on the road to the north all brim-full of pleasurable anticipation and excitement.

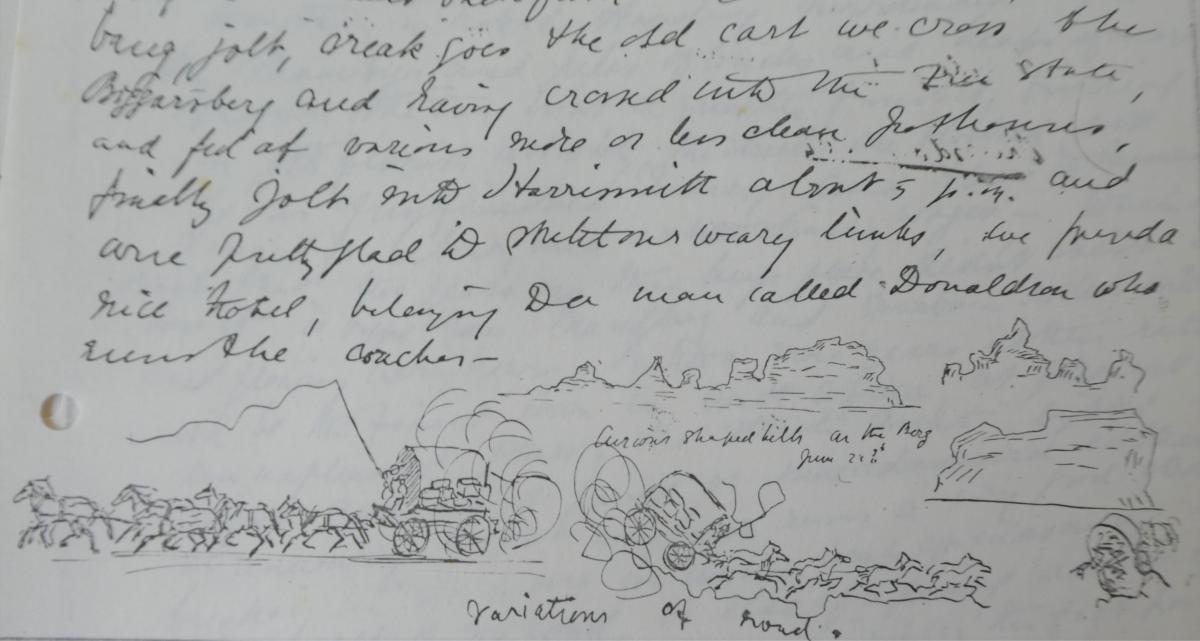

In order to have a look at all of this, to me, new country, I took my seat beside the coloured driver. The first sensation was one of disappointment: it was bitterly cold, while the country so far as any variety of scenery was involved, might have been the Sahara Desert, just brown veldt and big stones and then big stones and brown veldt. Still, I beguiled myself by reading rather a clever little book … Well, rattle, bang, jolt, and creak we traverse the Biggarsberg and descend into the Orange Free State.

From time to time, we are fed at various more or less clean wayside inns and finally, about 5 p.m. we jolt into Harrismith where we are pretty glad to stretch our weary limbs. We found a nice hotel belonging to a man named Donaldson, who runs the coaches.

Next morning there were five or six degrees of frost, and all the pools were covered with thick ice. Nevertheless, we were ruthlessly hauled from our beds at 5 a.m. and started off in pitch darkness. The road had now considerably improved, but the Free State thereabouts at least was scenically uninteresting, being perfectly flat with not a tree or a human being in the landscape. Ant heaps alone broke the level surface of the ground… in the afternoon a good many springbuck and blesbuck were on view close to the road. We had by this time got onto the farm of one Piet Koom, a fine old man, who strictly preserves his game and is most hospitable to coach-travellers, though neither he nor his wife can speak a word of English. No doubt the opening of the gold fields is putting a lot of money into the pockets of farmers. The one thing, however, that they are completely and solidly opposed to, is a railway, because so many Boers are employed as transport and post riders nowadays in connection with the mines and a railway would of course mean loss of employment to many of them.

On Saturday night we rested at the Vaal River at a store kept by a German who had served with the Boers in the 1881 War. No fires, horribly cold, and bed sheets which seemingly had seen a lot of service since last washed. We heard there that Mr [A.T.?] Oliff, who passed up from Natal last week, had been laying very heavily against the favourite for the big race – Earl Godwin, which belongs to David Symons – and Oliff is a man who usually knows something.

Sunday the 23rd saw us off again at 5 a.m., this time drawn by a team of mules which are more suitable for the work and go better than horses. It was as cold as ever, but having wrapped myself in my kaross, I at least felt it less than before. There is no denying that these post carts, with all their discomfort, do get over the ground. We cover from seven to eight miles an hour, and there is a stage every eight miles, where we remain only long enough hurriedly to inspan a fresh team, and then off again. On this day the dust was truly awful: it seemed to follow the coach – a choking, blinding and finely powdered screen…

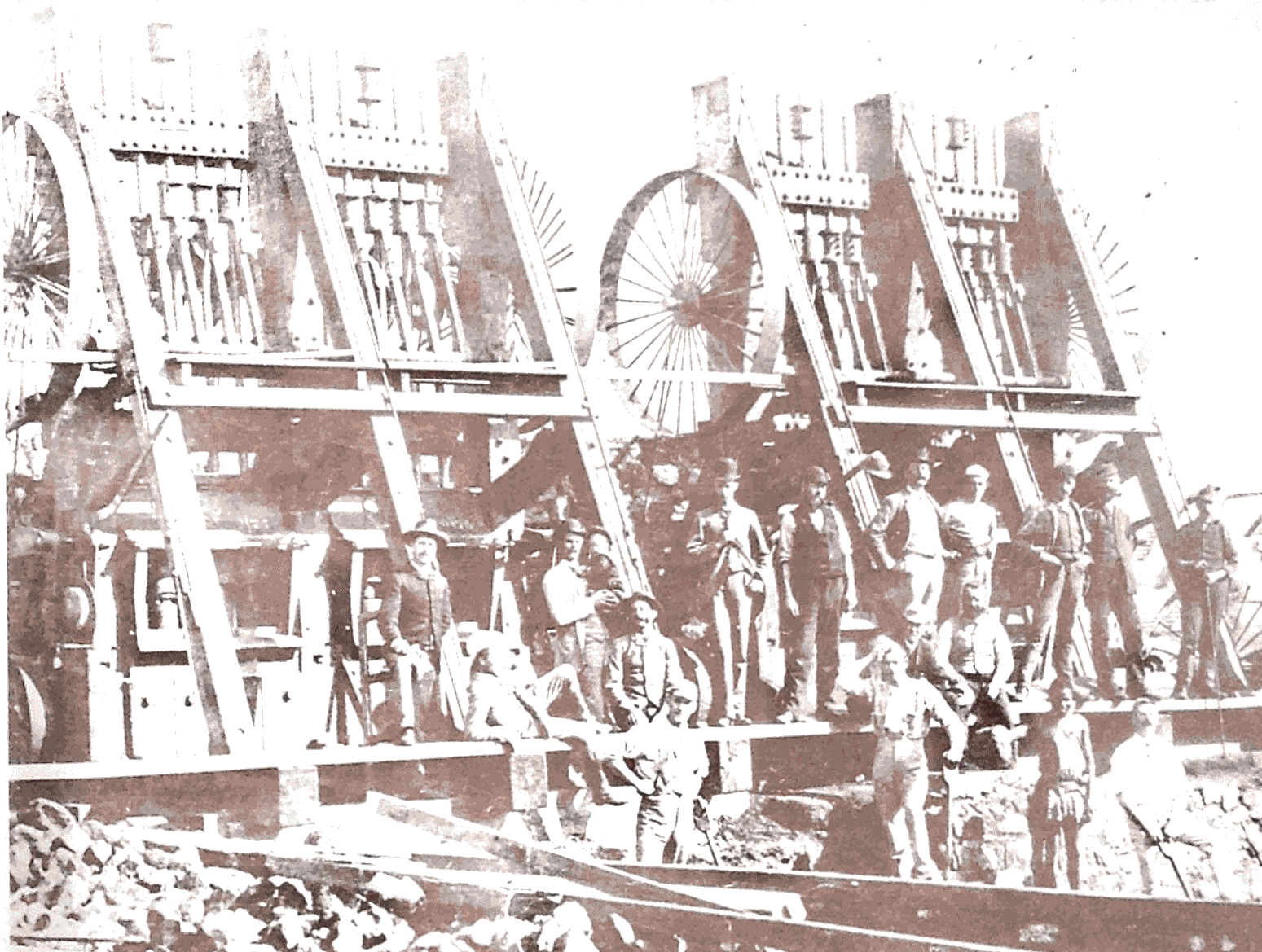

Rattle, bang, jolt; we reach Heidelberg about 2 p.m. On again, and at last, having travelled 300 miles, we sight Johannesburg. As the mail coach arrives at the commencement of the mining area, it is met by scores of vehicles – Cape carts, spiders, victorias, char-a-banc, in fact every inhabitant who can raise a conveyance appears to have turned out to greet its arrival. We are met and driven in by our hosts. The road runs for five miles along the main reef properties before it enters the town. The mines themselves outwardly resemble coal mines in Scotland or the north of England, except that they bear a less finished appearance. There are the usual hillocks of broken stone debris testifying to the excavations near the shafts.

Early photograph of mining on the Main Reef (South African Mining)

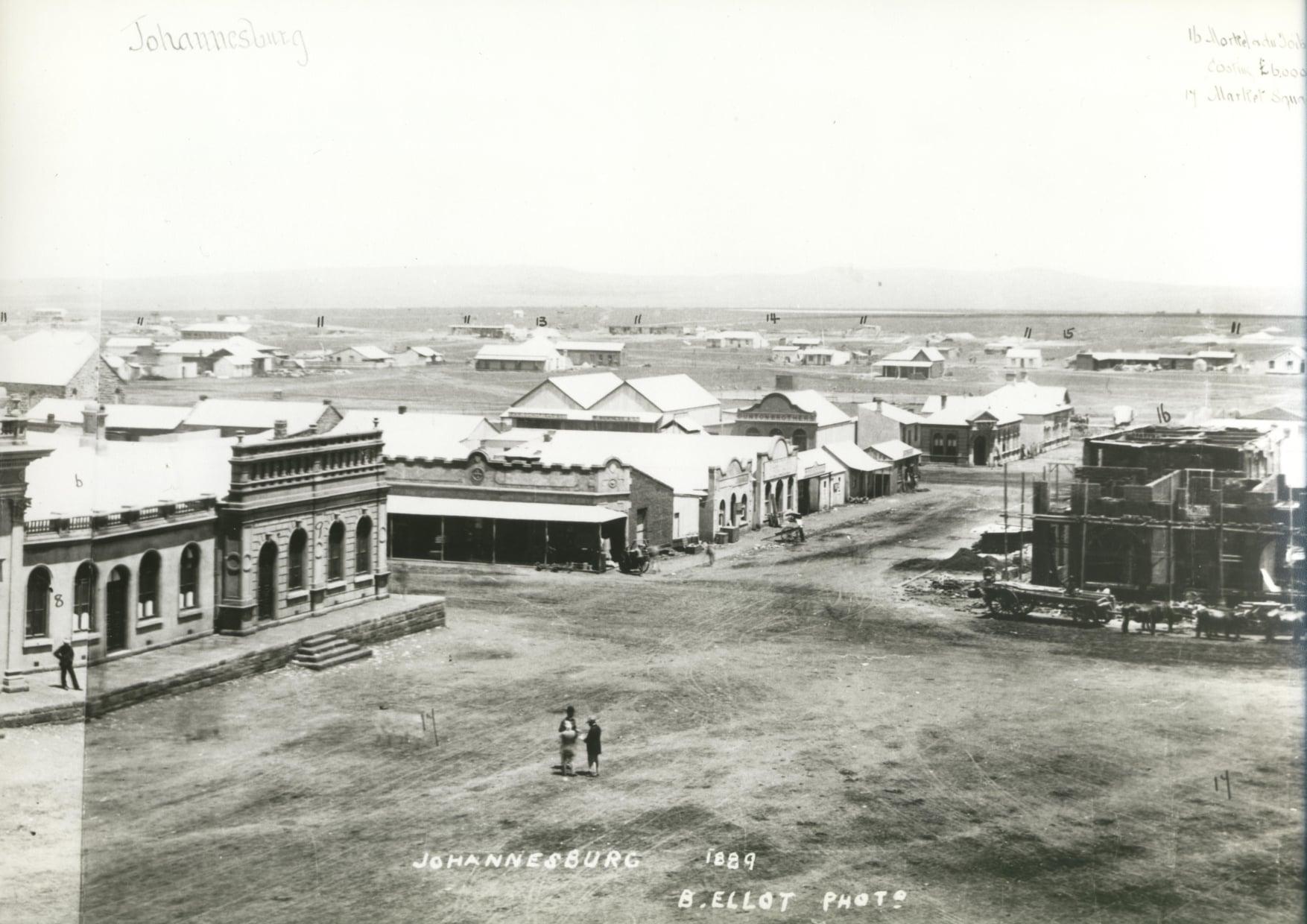

Johannesburg town itself is a scattered place of nearly 20,000 white inhabitants. The houses look as though they dropped from the sky, and just settled where they happened to fall without any design. One sees a fine and well-built house, superior to anything in Natal, standing surrounded by a number of mean tin shanties, piles of bricks, and heaps of mortar. Of course, the town is merely in the earliest stages of construction; building goes on with feverish activity; the streets are blocked with the material for unfinished houses. There is an intense demand for labour, and extraordinarily high wages are paid. When one reflects that two years ago this huge place didn't exist and now it is already bigger than Durban and Maritzburg together, and is growing every hour, one realises the force that gold has to collect a population in a short time. In two or three more years, at the present rate, it will be by far the finest town in South Africa. At present, it is an unpleasant place: the streets are not lighted at night, and are neither paved nor macadamized, so the unheeding night wayfarer runs a considerable risk of breaking his neck, or at least his leg, through falling over some unseen heap of masonry placed right in the middle of the road, or of reposing all night in some deep pit dug in the centre of the footpath.

Panorama of Johannesburg in the late 1880s (From Mining Camp to Metropolis)

Heart of the city in 1889

The principal drawback – it amounts to a plague – is, however, the dust; This is simply indescribable; there is no escape from it; every passing vehicle raises a stifling cloud that hangs indefinitely in the air, and by evening the town, viewed from a distance, seems veiled in a dense yellowish cloud. So fine is this dust and so insidious, that it penetrates every pore of the skin. One cannot keep a shirt even decently clean for half an hour, and washing being expensive, the residents’ bills are naturally proportionately high in this respect. In the summer, when the rain has fallen, the dust becomes mud, which is said to be quite as bad in its own way – at least I'm sure it can't be worse! It must be an unhealthy place, both on account of this dust, and also from the apparently light-hearted disregard for the fundamental rules of sanitation. Water is scarce and bad. The cabs seem to take a fiendish delight in doing their best to run down pedestrians – you cannot hear them coming on account of the thick coating of dust on the ground, and their approach is similarly veiled from the eyes. Luckily there was no wind during our visit, or I do not know how we should have breathed at all.

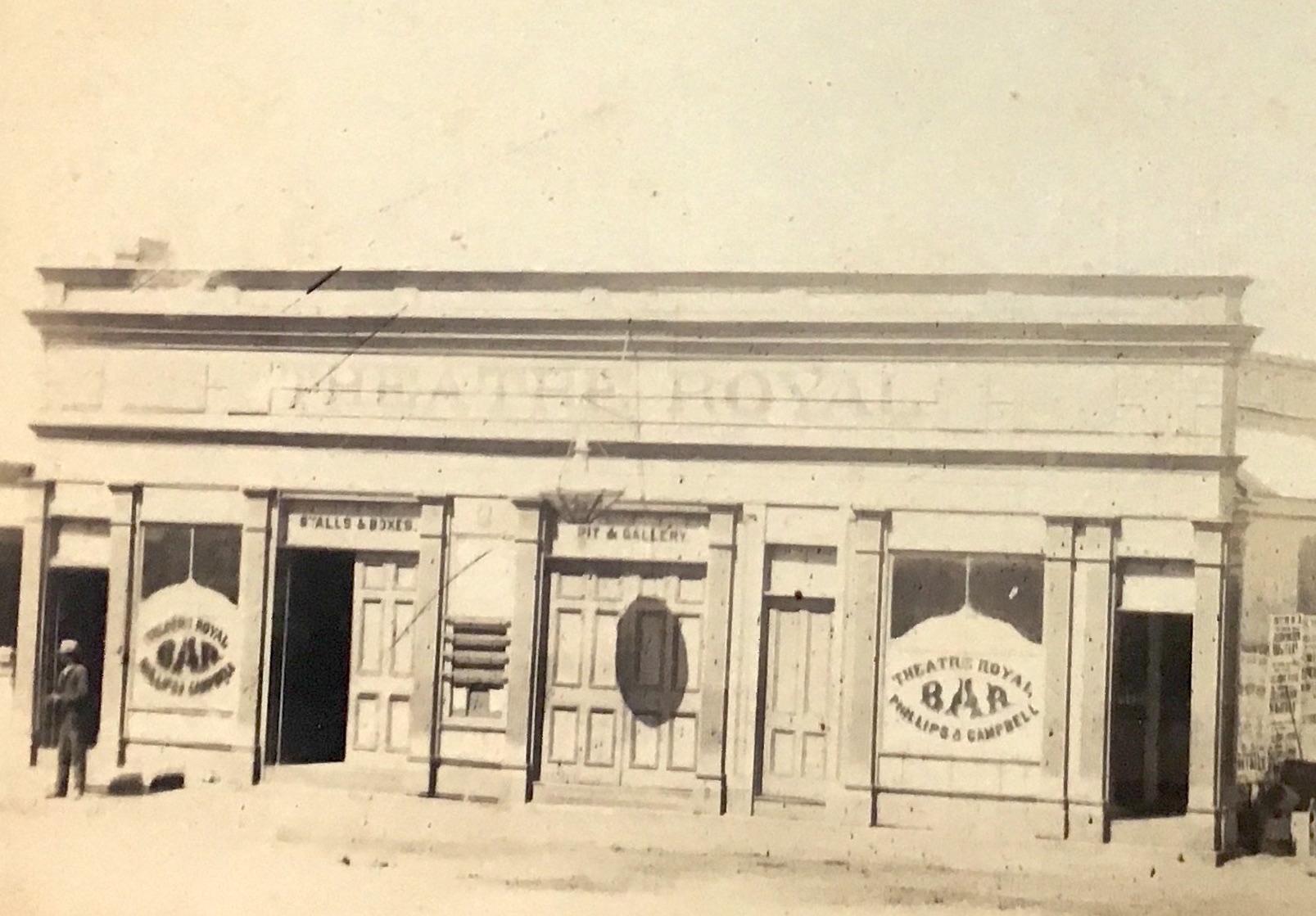

However, in spite of all drawbacks, things are very gay socially; the theatres crammed every night to; concerts on Sundays, dances and entertainment of all kinds going on: a great contrast to sleepy Natal. What struck me a good deal was the greater number of well-dressed women I saw than expected, they are a great lot of them – London demi-mondaines, who have scented ‘oof’ [money] and flocked to the place, not to be disappointed either. They have a very good chance of marrying well too in the end.

Theatre Royal in 1889 (Museum Africa)

I am staying with the owner of Earl Godwin and other horses, the other two with J.B. Taylor. Symons’s stables are just behind his house. It seems Oliff was right as Earl Godwin will not run as he was got at some time ago, a pitchfork or similar weapon having been stuck into his hock, which is now as big as a man's head and is being blistered. Fisherman, the second string, will however start, and the stable thinks will win the big race. On Monday the betting was 7 to 2 Fisherman, Mariner, and Tester. Lollypop is fancied by the public, but has been tried with Fisherman at the weights, and well beaten.

Strolling down to Heights Hotel, which is the principal rendezvous at present, on the first night of my stay, I found gathered there all the principal bookmakers, as well as [Frederick?] Couper and his brother [James] the prize fighter. The latter is a small man but is nearly as broad as he is long. He looks as hard as nails and is very quiet in manner. From his appearance he should be about forty, which is too old for prize fighting. Couper himself, of Madagascar fame, whom we knew well in Natal, is less subdued. He says the other night he knocked out a crowd of men who attacked him and afterwards the police when they arrived on the scene. He then, he says, had a drink with the landdrost, before whom he had been hauled and went on his way rejoicing. According to him, the landdrost at parting remarked, “We are all very glad to meet you but shall still be more pleased to see the last of you!”

During my explorations a day or two later, I came across the opposition – [Wolff] Bendoff – who is a great big, rather slouching fellow, very strong, and said to be a marvellous sparrer, but to my idea he has not the “heart” of Couper, and if the latter gets in one or two of his celebrated right handers, Bendoff might curl up. At present, anyhow, while Couper is in hard training, his opponent appears to be getting up his muscle through a training course of whiskey and soda – at any rate I myself had two with him and left him still hard at it in the Bodega [Hotel]. The latter by the way, has a very fine bar, sumptuously upholstered and fitted.

On Monday I went with my host and party to see the Mikado. Symon lives with his partner and two brothers named Farrar, one of whom [George] is the Turf Club handicapper.

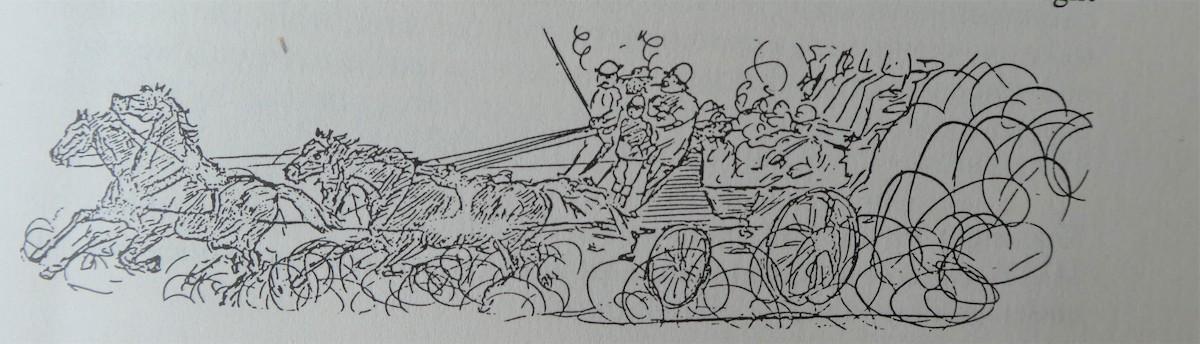

Tuesday 25th was the first day of the races, and about a dozen of us started out on board a most extraordinarily old four-in-hand drag which is said to have belonged to Sir Hercules Robinson but looks as if it might have well carried the first governor of the Cape.

Sketch of Sir Hercules Robinson's four in hand

Every one of us was in the highest spirits and confident of making a fortune. The trainer, McLea, the stable jockey (in colours) and two others, including the coloured driver, were on the box seat, and the rest of us inside smoking the largest of cigars. The road was rather reminiscent of Epsom on Derby Day, congested with vehicles of all descriptions, and the dust so thick it was difficult to avoid collisions. I had, on the previous day, made up my mind to back Mariner for the big race but was partly put off by a hint that he might not start. It seems his owner, Colonel Ferreira, has got involved in some legal trouble in Pretoria, and there was some talk of a firm of lawyers stopping the horse from running – quite likely as things eventually turned out, all part of a plan to lengthen the odds. Also, my host was very keen on his own horse, Fisherman, and even offered to let me stand in on his book. So, in the end we all went and backed Fisherman heavily at threes, and by the time the race started, the public was mostly on also and had him run up to a hot favourite at evens. Being, however, a canny Scot, I thought I would not put all my eggs in one basket, so I placed a small sum on Mariner at twos. The race needs little description. After seven false starts caused by Mariner, which caused Colonel Ferreira to shut up his glasses in a rage and say it was all over for him, when they did it last get off, Mariner was never touched, and won with about three stone in hand: Tester second, and Wanderer third. Fisherman would have been fairly close up had he not strained his shoulder half a mile from home, and even then he finished fourth, which was not bad for a horse that walked dead lame into the paddock. I came out a bit on the right side.

It was a great crush at the sumptuous luncheon after the big race. I held a complimentary ticket admitting me all over the stands, paddock etc. I should think there must have been 10,000 people present and it looked like an English racecourse with its shooting galleries, coconut shies, three-card men and so on. A sign of the times I noticed, was that the whole of the large force of armed police, mounted and foot, was entirely composed of Englishmen, under English superintendents, though paid by the Boer government, fine looking men they were too; they all carried hunting crops which were very useful for the stray dogs. The Ring was in great force and maintained a deafening roar all the time, while the Totalisator had so many patrons that it was next to impossible to force a way in. Of course, there is not an atom of grass anywhere, nothing but thick dust. The grandstand was full of smartly dressed ladies.

That night we all went again to see the Mikado. The principal lady is a Miss Benister – who had acted a lot in D’Oyly-Carte companies. She acts and sings nicely and is good to look at.

The following day, there being no racing, Rimington, Yardley, and I went for a ride on borrowed steeds; Rimington on a tall and beautiful white animal with flowing mane and tail, which looked as if it might have been in a circus. The meetings being on alternate days, on Wednesday night the usual selling lotteries for next day were held at the Bodega. Oliff appeared while they were in progress, and commenced laying heavily against Mariner, one of his bets being £3 000 to £1 500. People began to wonder what was wrong, since 5 to 4 was the market price. Then a rumour went around that Ferreira had given Peters and Oliff the refusal of Mariner at £1 500, up to 11 a.m., the hour of the first race. However, having already backed the horse, I thought I would stick to it, though while on the course I put a hedging bet on Upset, another of our stable. Mariner’s number went up all right and, though carrying 21 lbs penalty, he came again away from his field, and won with a lot in hand. Upset made a good show, and led to the straight, when he was beaten and finished fourth. We all backed him at 20 to 1 for the last race of the day and, though his jockey lost ten lengths coming round the bend, he lost the race by a short head only. In fact, he might have won if some jockey behind, who may have had an interest in the winner, Chanticleer, had not shouted to the latter’s jockey when he saw Upset making his effort, “Look out Whiting!”

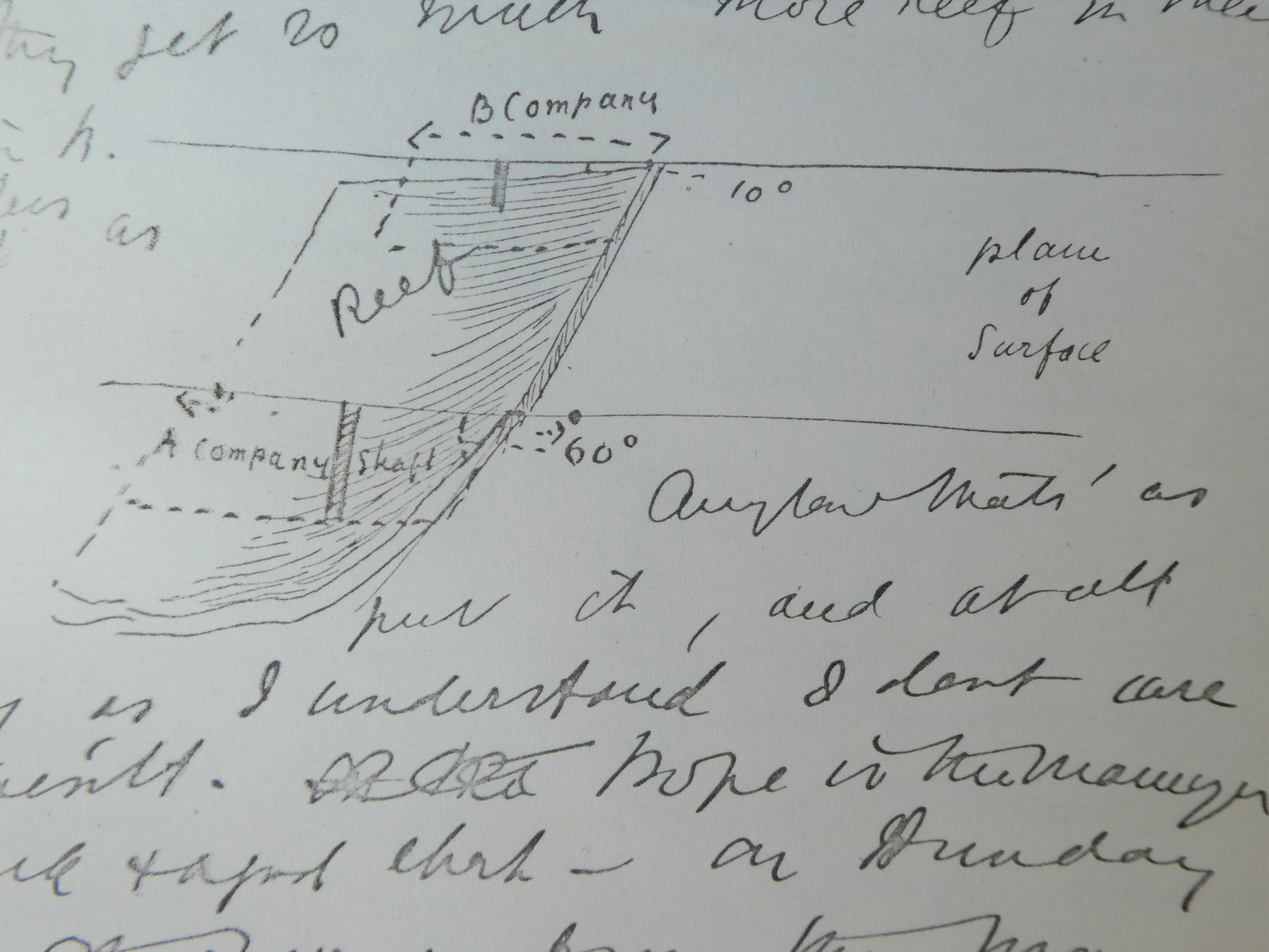

On Friday – a second day off – I drove out to the Simmer and Jack line with George Farrar. We went all over the mine, which included being lowered a hundred feet in the bight of a rope, and crawling through long tunnels 18 inches high. I saw five or six pounds of quartz crushed, and then panned in a basin, leaving a little heap of gold dust at the bottom. The present dimensions of the mine are 178 feet vertical and 368 horizontal. Two hundred natives are employed (a lot of them dying, and some lying about still unburied). There are fifty stamps; all three reefs tapped, and 800 ounces of gold were produced at the last crushing. The reef is rather flat, which is a drawback, as naturally the steeper the dip of the reef, the more of it is likely to be on one property. The manager's name is Hope.

Scenes from the visit to the Simmer & Jack Mine

On Sunday I went with the other Farrar to see the May Consolidated; this is also a very good mine, the shares at present at a reasonable price. There are twenty stamps working, and fifty more on the way, while all the reefs are at an angle of 65 degrees, which ought to make the production a rich one. I was told that a narrow reef is preferred to a wide one, as the latter is usually not so rich. As a rule, the reef varies from 18 inches to 6 feet, the 18-inch one being the richer. It is absurd people down country and overseas belittling the Johannesburg mines: the Rand has an immense future before it. All the mines are hard at work, and the crushings along the main reef improve every month. I am sure such mines as Simmer and Jack’s, Jumpers, Mays, Vogelstruisfontein, and Salisbury’s are sound investments, some indeed already pay good dividends. Of course, the shares are in some cases at too high a level, and they may drop a bit; but they say the boom is not expected much before September. I’m devilish glad to have been up here and seen with my own eyes.

Sketch of the Reef

Early stamp battery in Johannesburg

Sunday was an unlucky day's racing. Mariner, meeting horses on three stone worse than the opening day, ran a good second to Tester in the big race of the day. None of Symon's horses won a race all through the meeting, and he must have come off pretty badly. It is hard to understand about Candlemas, a horse recently imported from England. He was rather fancied for the Derby, and he finished second to Ormonde in the Eclipse Stakes of 1886; yet, though he looks fit enough, he does not seem able to make any show out here.

Much fighting on the course of the last day, everybody seeming in a bad temper and feeling pugnacious. On Saturday night after the races there was rather an amusing fight, arising out of a difference of opinion on the race course. A Jewish bookmaker had been standing on three boxes, when a man rushed up and kicked the middle one away, the bookmaker falling heavily on his behind. They had words on the spot, but the crush then separated them. They met again later at the Bodega, and at once fell to, when the gentile, a small but very fierce man, got rather the best of it. His opponent then went out, and presently returned with his “Big Brother”. The latter, his middle finger adorned with a large diamond ring, stepped promptly up to an inoffensive person, quietly having a drink at the bar, and smote him between the eyes. He had scarcely done so when the man he had intended to strike came at him like a whirlwind, and they both fell down together and rolled about amongst the feet of the crowd which by this time was very large. “Nobbie” Clark, the Natal bookmaker, had a bet of a level £5 that he would sell a certain number of expired racing cards in the Bodega. Accordingly, on the Friday night before the last day's racing, when we were all awaiting the new cards, he rushed in with an armful and had sold about twenty for sixpence each before anyone found out. He then promptly fled before vengeance could be taken.

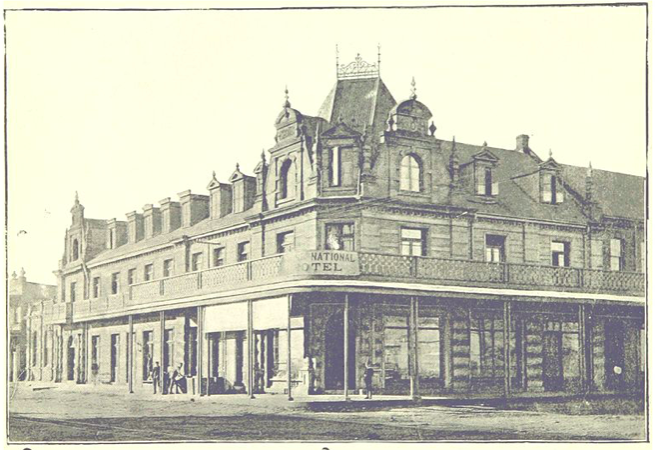

On Sunday night I dined at the Grand National Hotel, which is not quite finished yet, but should eventually be rather a fine place.

Grand National Hotel inthe early 1890s

On the following Monday, I drove out to Jeppe's township, to the best house on the Rand. [Charles] Leonard occupies it, and has Bowden, wicket keeper to the English cricket team, and a young fellow called Ellis staying with him, besides an artist named Cohen. We had intended to go to a dance after dinner, but being right out at Doornfontein, and having dismissed our cab, we decided to go to bed instead. Leonard rents the place for £600 a year. On the following morning, I walked back to town and there met Captain Robertson, who left my regiment before I joined, and who says he is now making £6 000 pounds a year as an expert on properties!

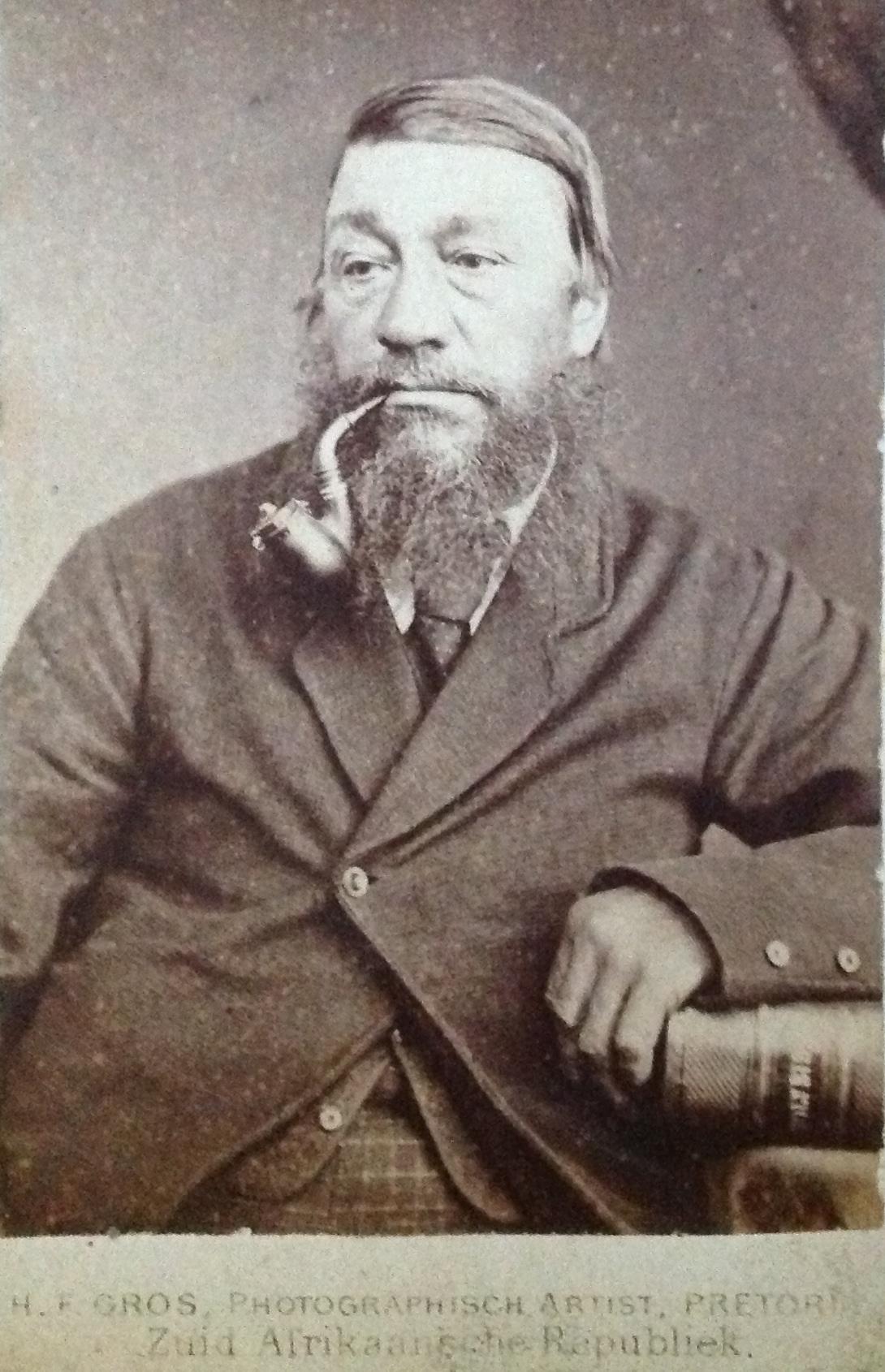

The coach started on the return journey at 5 a.m. on Wednesday 3rd July, and the three of us duly embarked on it. Rimington and Yardley had been taken over to Pretoria to call on President Kruger, whom they found sitting on the stoep of his house in shirt sleeves, smoking his big pipe. They had a good introduction, so he was very nice to them and gave them coffee.

Paul Kruger (HF Gros)

We staggered out to the coach in pitch darkness and 10 degrees of frost to find the interior crammed full, including a stout coloured woman. It was so cold that the curtains had to be closed, so the atmosphere may be imagined. Yardley was next to the coloured lady, but I was opposite, and in a way worse off, as with each more than usually violent lurch of the coach, I was projected onto her lap. Otherwise rather a nice lot of passengers.

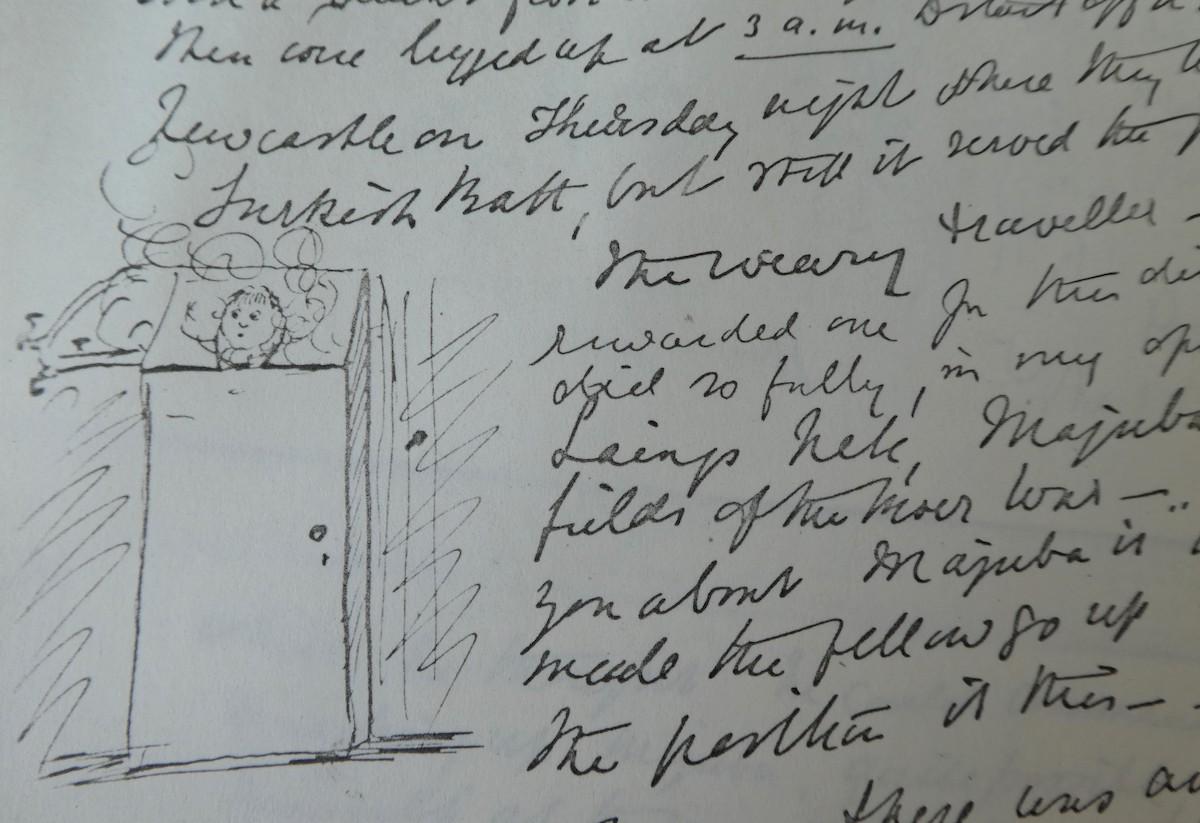

This time we took the Newcastle road to Natal and regretted having done so. The coaches were bad, the roads worse, the distance longer than by the other route, and the accommodation on the road inexpressibly awful. We reached Newcastle on Thursday night where they have a primitive Turkish Bath but, still, it served the purpose of refreshing the weary traveller.

Sketch of the primitive Turkish Bath

The only thing that rewarded one for the disgusting journey and that did so fully In my opinion was seeing Laings Nek, Majuba, and the other battlefields of the Boer War. The first thing that strikes you about Majuba is what the devil ever made the fellow go up there! … Looking at the ground, we thought the General [Major-General Sir George Pomeroy-Colley] deserved what he got, though it was bad luck on his personnel. (How very differently we should have arranged matters of course!) …

Majuba cemetery

Words cannot express our feelings of bliss when at last we found ourselves in the train at Elandslaagte and saw the last of the hated post cart in which we had spent so many miserable hours. How delightful would be a railway to Johannesburg! The line is laid for 15 miles north of Elandslaagte; but the cutting, bridges, culverts etc. are completed right up to the Transvaal frontier beyond Laings Nek and only 160 miles from the Rand. The early hours of 6th July saw us back in Maritzburg after a very interesting and pleasant fortnight and, after some supper in my quarters, we eventually got to bed at 3 a.m.

Main image: A page from the diary containing a sketch of scenes from the coach journey to Johannesburg.

Thank you to Jane Carruthers for finding, transcribing and editing this article.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.