Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

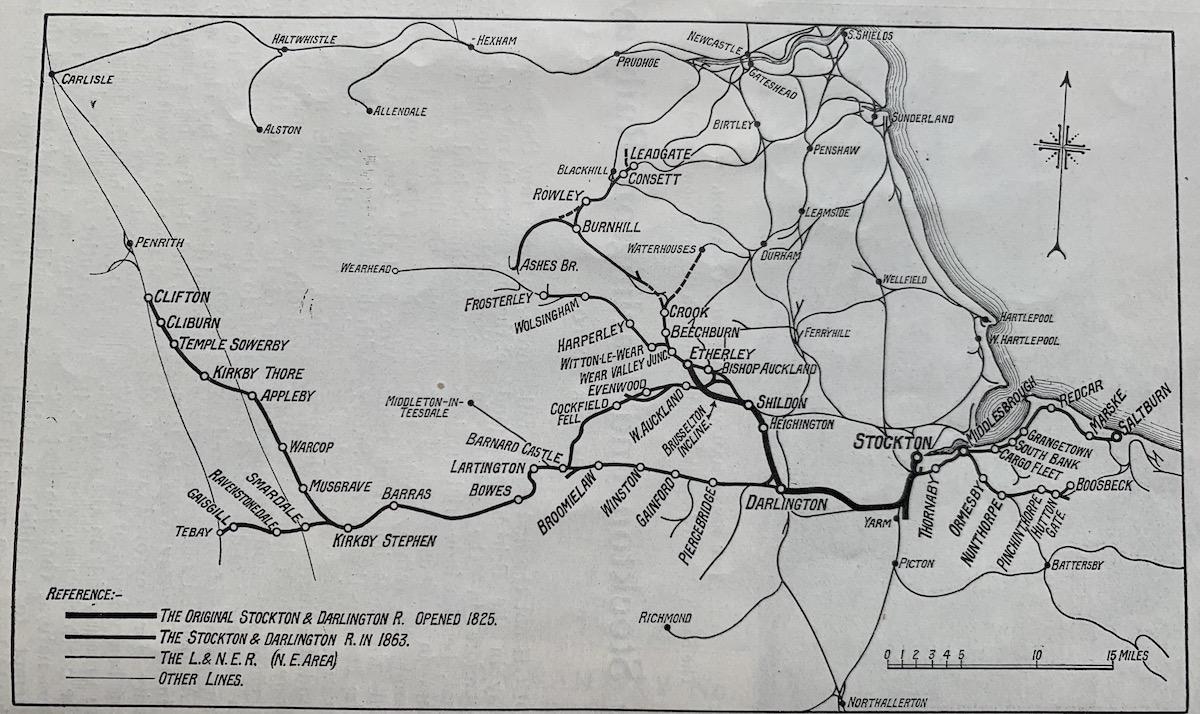

Should you search on the internet for Shildon, a small town in County Durham in the North East corner of England, you will find out that it has house prices one-tenth of those in London, but that is not the town’s major claim to fame. Shildon is world famous for being the cradle of the Railways (a.k.a. Rail Roads), which were launched in the first quarter of the 19th century. Its location on the eastern edge of the Auckland (south-west Durham) coalfield, made its proximity to the coal mines an ideal spot for a rail head for a proposed railway line from Stockton-on-Tees via Darlington; the celebrated Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR).

Front cover of the 1975 Souvenir Guide

Map of the route over time - click here to view a larger version (The Railway Magazine)

The S&DR opened on the 27th September 1825 after what was a long period of gestation, as the need for better transportation of coal from pit to port was first realised in the mid 18th century. There was a talk of a canal and then a tramway but the business men of Stockton and Darlington could never agree on a way forward and thus “Nowt” (naught) was done, which left them at a perennial disadvantage to their competitors in Newcastle-on Tyne.

At the beginning of the 19th century the long established coal mines of Northumberland, close to Newcastle, were in convenient proximity to the Staiths (coal discharging platforms) on the banks of the River Tyne for the easy transfer of coal into “Keels” (shallow draught barges) that would sail down river to fill waiting seagoing ships that would sail onward to London. The old saying of “Carrying coals to Newcastle”, a metaphor for a pointless exercise, was because Newcastle had plenty of coal already.

The same thing could not be said for the coalfields of south west County Durham where the mine owners were handicapped in getting coal to market by the long overland haul on poorly surfaced roads to Stockton, where the River Tees became navigable to the open sea. No one has ever heard of the saying “Carrying coals to Stockton”. The coal in the ground was therefore near worthless until such time as a better and cheaper means of conveying coal in bulk was found.

Consequently, as early as 1768, a survey had been completed by Robert Whitworth (the son-in-law of canal builder James Brindley) for the purpose of proving the viability of a canal from Stockton to Winston Bridge, via Darlington. The estimated cost for the enterprise was £64 000 but the “green light” was never given, and the project was left to “wither on the vine”. In the years 1796 and 1800 further canal schemes were advanced but they were likewise not carried through. 10 more years would pass by before the subject of a link to the Auckland coalfield was again mooted, but this time an alternative to the canal in the form of a horse drawn tramway was being touted.

On a tramway, a horse could pull a train of wagons having a gross weight of up to 10 tons, whereas on an unsurfaced road it could only pull a wagon load of one ton; therefore tramways were considered a great improvement over road haulage. Tramways were not a novel idea as they had been in use underground and at the pit head on the coal mines for several decades, but had until then only been considered for short haul purposes. The 25 miles (40 km) or so from pit to port was considered long haul for the day and the accepted thinking was that gravity would be used for the downhill sections (with the horse being given a free ride on a Dandy Cart attached to last wagon) to the port and that horse power would be used for level and uphill sections (hauling empty wagons back). On the steep inclines adjacent to the mines rope haulage was applied using stationary steam engines, fuelled by coal.

During the Napoleonic Wars the cost of horse feed had increased steeply, so much so that mine owners were looking for cheaper ways to haul coal. It is a modern day fallacy to imagine that horses were a cheap form of power; in reality the cost of using them could rise or fall with the price of hay and oats. As coal itself was the product of the mine, it was not considered an overhead and its use for firing a boiler of a mobile steam engine (locomotive) had much to recommend it. The selfweight of the steam engine was a problem until such time that rails on which the engine would run were made stronger; hitherto rails were made from either cast iron or wrought iron square bar, both of which had a small load-bearing capacity although adequate for the fully laden wagon of the time. Until a better rail was found the steam engine was a non-starter. The lack of a suitable rail section had stopped Richard Trevithick in his tracks (pardon the pun), he being the first to realise the potential of a high pressure steam engine running on rails when he constructed one for the Penydarren Ironworks, Methyr Tydfil in South Wales. On the 22nd February 1804, in order to settle a bet between two mine owners, his steam engine hauled 10 tons of iron, 70 men and 5 extra wagons for 10 miles at 5 mph and was deemed a success, but alas the track, having been laid down for horse drawn wagons was not up to the job and suffered damage. History will credit him as being the pioneer who invented the steam locomotive, but he would not see its further development and would leave it to others to make it an engineering success.

Necessity is the mother of invention and it would be the mine workshop mechanics of the North East, Blenkinsop, Hackworth, Hedley, Stephenson, et al, who would, by methods of trial and error, be the ones to overcome the problems arising from the new technology of steam power and make the steam engine practicable. Many men could lay claim to the title of being the “Father of Railways” but one man deserved the sobriquet above all others and he was George Stephenson (1781-1848).

Book cover showing George and Robert Stephenson

George Stephenson did not invent the steam locomotive nor did he invent the track on which it ran, but it was he who had the vision to see the possibilities of a network of railway lines on which trains would run carrying passengers and goods. During the construction of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (1822-1825) he once told his assistant John Dixon of his dream and Dixon recalled that “George Stevenson told me as a young man that railways will supersede almost all other methods of conveyance in this country…(they) will become the great highway of the King and his subjects” (quoted from Ref. 1). Furthermore when he was consulted about prospective railways he always recommended that the same rail gauge be used with a prophetic remark: “They may be a long way apart now, but they will all be joined up one day”.

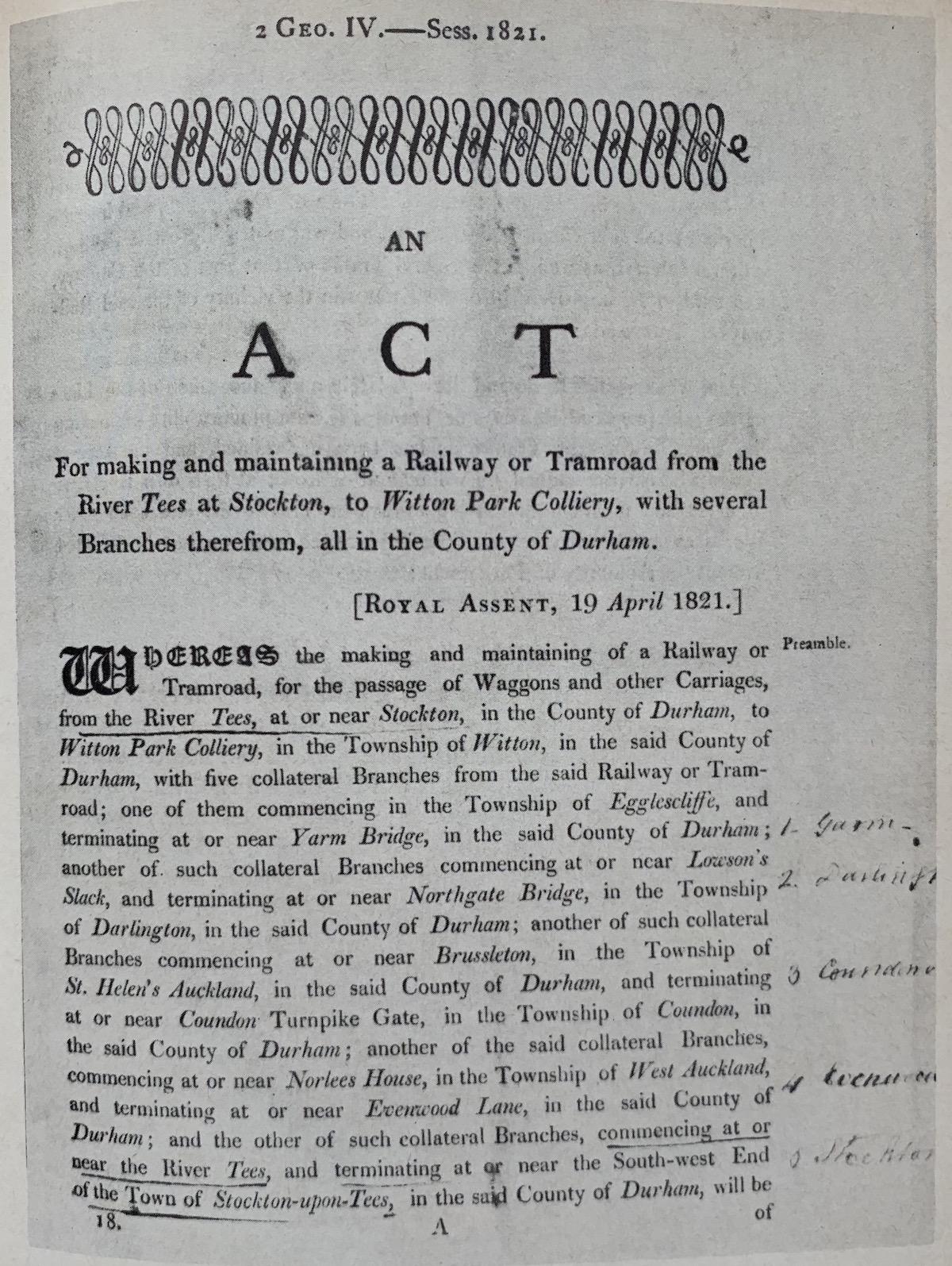

George Stephenson’s involvement in the S&DR came late in the day as he had his first meeting with Edward Pease (the main financial backer) on the 19th April 1821, the very same day that the “Stockton & Darlington Railway Act” was given Royal Assent, although it was unbeknown to both men at the time. The upshot of the meeting was a verbal agreement and a shake of hands and Stephenson was made the Engineer of the S&DR (one small step for man, one huge leap for mankind I’d say).

Front page of the Act (The Stockton & Darlington Railway)

Another George, George Overton, a Welshman well versed in the building of tramways in South Wales, had been involved in several surveys of the proposed route of the S&DR, right up until the time of the final Railway Bill being presented to Parliament. It must have come as a terrible surprise to find that he had been overtaken at the last hurdle and presumably he returned to Wales overwhelmed with disappointment. To him a Rail Way implied a horse drawn tramway, whereas to Stephenson it meant steam traction on rails and a technological leap forward.

I shall not go into the story of the building of the line, suffice to say that George Stephenson and his son Robert re-surveyed the route so as to give it more gradual curves and gradients so as to better suit the use of a locomotive as motive power and that it would take 3 years to build (1822-1825). He was also able to take advantage of a technological breakthrough, for the rolling of malleable (wrought) iron rails, in 15 feet lengths, was now a reality. The process was patented by John Birkinshaw (in 1820) and rails were first laid down at Bedlington Iron Works and they proved to be far superior to cast iron rails that were prone to crack; had Trevithick had the benefit of such a rail, history may well have panned out differently.

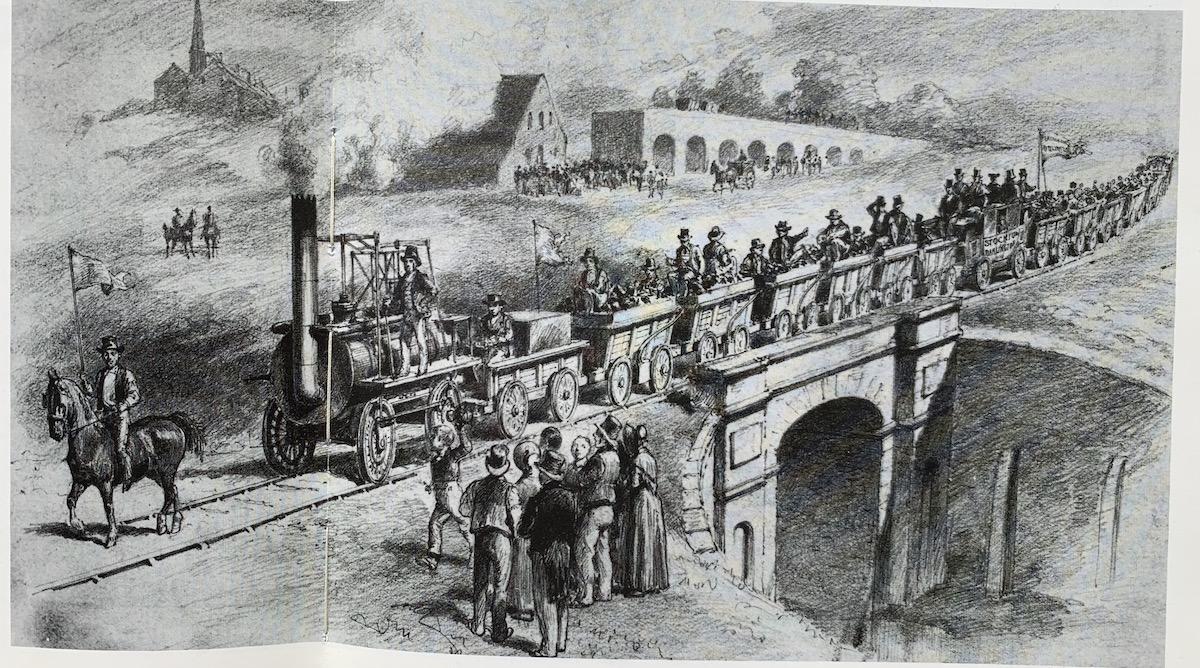

On the 27 September 1825, George and his brother James were the men entrusted with driving and firing the locomotive No. 1 – “Locomotion” when she pulled away from the Masons’ Arms, Shildon on the first train to Stockton with 600 passengers on board (in coal wagons fitted with seats) with many thousands of people lining the route. The steam engine not only pulled a train of wagons it also symbolically pulled the world into the mass transit era.

Steam engines 100 years apart. 'Locomotion' on the left. (The Railway Magazine)

Masons Arms (The Stockton & Darlington Railway)

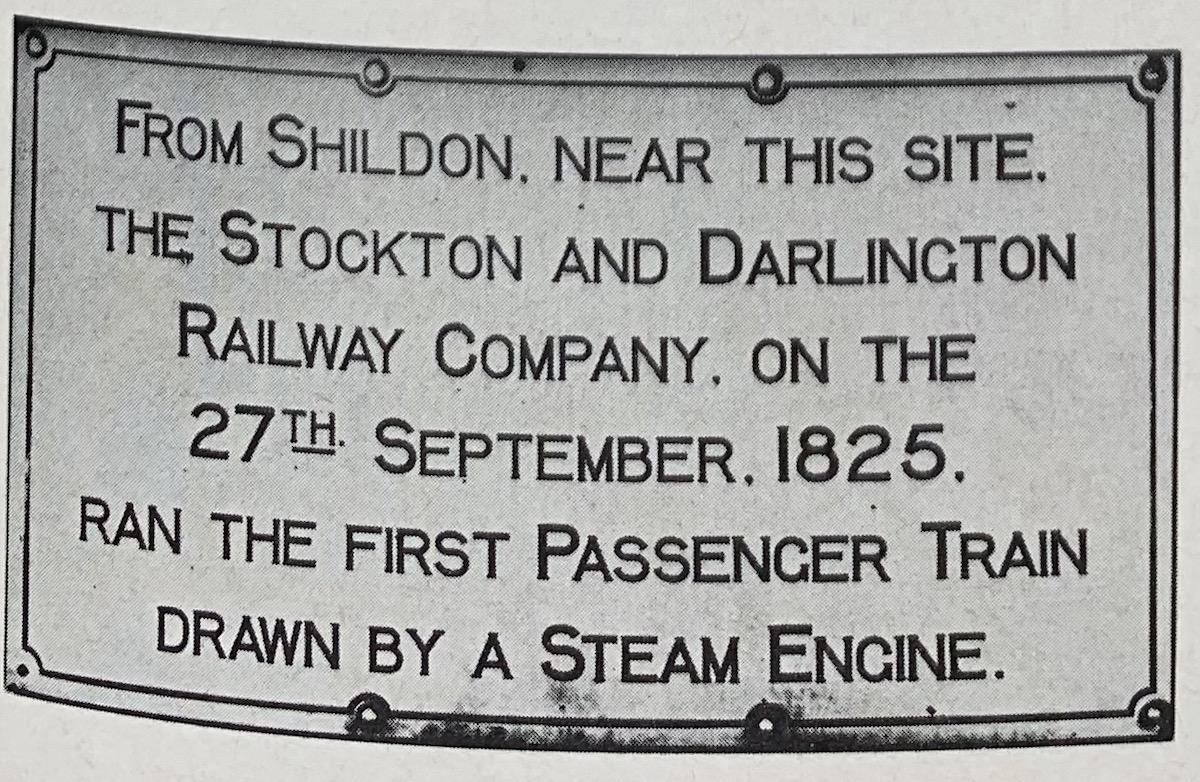

Plaque commemorating the historic moment (The Stockton & Darlington Railway)

It was a day of great celebration which heralded the start of the first public railway in Britain (and hence the world), for it would not only carry coal but also all other types of merchandise, including passengers. The celebration of the opening of the S&DR has been repeated every 50 years since with the next, the bi-centenary due in 2025.

Painting of the opening of the railway displayed in the Darlington Museum (Souvenir Guide, 1975)

Today Shildon has become a Mecca for railway enthusiasts, as on the site of the former wagon works now stands a railway museum second only to the National Railway Museum – York; the museum is named “Locomotion” in honour of the first locomotive to work on the line.

Main image: Locomotion going over the Skerne river bridge (Trains for Young People)

Postscript: On the 27 December 1830 an eastward extension of the S&DR was opened to a hamlet, on the south bank of the River Tees, downstream from Stockton; that hamlet was to burgeon into the town of Middlesbrough.

References and Further Reading:

- “The Life of George Stephenson and of his son Robert Stephenson” by Samuel Smiles, published by Harper Brothers, 1868.

- “George and Robert Stephenson – the Railway Revolution” by L.T.C. (Tom) Rolt, first published by Longman, 1960, now in Penguin Paperback.

- “The Railway Magazine – Special Railway Centenary Number” July 1925.

- “Early Railways” by J.B. Snell, published by Octopus Books, 1972

- “Stockton & Darlington Railway 1825-1975, Rail 150 Exhibition Steam Cavalcade”, a Souvenir Guide, 1975.

- “The Stockton & Darlington Railway” by K. Hoole and published by David & Charles, 1975.

- “Works of Man” by Ronald W. Clark and published by Century Publishing, 1985.

- “Locomotion – the National Railway Museum at Shildon” Guide Book, 2012.

- “History of Britain’s Railways” by Julian Holland and published by Collins, 2015.

- “Friends of the Stockton & Darlington Railway”, web site: www.sdr1825.org.uk

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.