Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the middle of August 2016 employees from South 32 began the move from the landmark 6 Hollard Street in downtown Johannesburg to offices in the Worley Parsons Building in Melrose Arch. The move marks the end of a long and historic association that the firm (via its predecessors) has had with the Johannesburg CBD.

Old South 32 Head Office at 6 Hollard Street (previously the BHP Billiton / Gencor Head Office)

Worley Parsons Building Melrose Arch (The Heritage Portal)

South 32 was established in 2015 when it was unbundled from BHP Billiton but its origins go back to 1895 when the General Mining and Finance Company was formed. After a long and complex corporate battle in the 1970s, General Mining acquired Union Corporation (founded in 1897 as A Goertz and Company) and the General Mining Union Corporation Ltd. was born (known as Gencor by 1980). In 1994, after lengthy negotiations, Gencor took control of Billiton from Shell to become a global giant. Then in 2001 Billiton merged with BHP to become one of the biggest diversified mining companies in the world. This very simple summary hides a remarkable and complex history. For those interested in the many corporate twists and turns up until 1995, the book Through Rock and Fortress: The Story of Gencor 1895-1995 makes for fascinating reading.

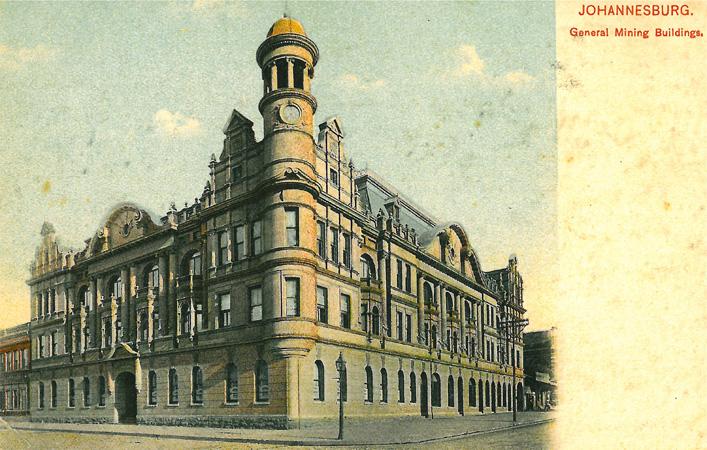

The First General Mining Building was designed by Philip Treeby and located at 76-78 Main Street - part of the site on which the current building stands. Various sources state that it was built in 1903/4 but in Through Fortress and Rock a caption to a picture states that an earlier building, the Grusonwerk Building, was the first headquarters and was 'substantially renovated in 1903'. It would be great for more details on this potential transition to emerge from the archives.

Grusonwerk Building - General Mining's first headquarters in Johannesburg (Through Fortress and Rock)

First General Mining Building (From Mining Camp to Metropolis)

An early postcard of the General Mining Building (retrieved from Artefacts)

The building was in the heart of Johannesburg's mining and financial district surrounded by the Chamber of Mines, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and other illustrious names. It survived until 1951 when it was demolished to make way for a larger head office. In one of his Citi Chats, inner city champion Neil Fraser mentioned that a stained glass window from the building was salvaged. We assume it was incorporated somewhere in the new building but this needs confirmation.

The 1950s facade (The Heritage Portal)

Over time the firm acquired the remaining buildings on the block and in the early 1990s management took the decision to adapt them to create a massive head office building. The 1950s facade and the beautiful Art Deco Union House (also know as Harcourt House) were retained in a highly successful project. The models below (housed in the lobby of the building) show the extent of the work.

Model of the city block before rationalisation

Model of the city block after rationalisation

Another angle of the new model. The architectural firm (Taljaard Carter Architects) received a conservation award for their work

The facade of Union House was preserved (The Heritage Portal)

The new head office opened in 1995 coinciding with Gencor's centenary celebrations. A well publicised spat between Nelson Mandela and FW De Klerk occured during the opening festivities. Tony Leon was also in attendance and gave the following recollection of the showdown in his book Opposite Mandela*:

I duly presented myself on a balmy Friday evening in downtown Johannesburg at the rather splendidly reconfigured Gencor building. We were gathered, the leaders of South African corporate and political leadership, in a marquee set up outside.

I was not surprised by the presence of President Mandela, there to provide the keynote speech. After all, he set great store by obtaining the buy-in of business leaders, both to fund his cause and to keep faith with the course of the new South Africa.

Equally unsurprising was the presence at the Gencor bash that evening of FW de Klerk. Gencor, after all, was the latest corporate iteration of General Mining, which, with some assistance from Anglo’s Harry Oppenheimer, had in the mid-1960s become the first Afrikaner-controlled mining corporation in the country, nearly eighty years after gold had first been discovered on the Witwatersrand back in 1886. De Klerk was the inheritor of a patient political tradition that, in matters economic at least, set considerable store by the empowerment of die volk (the people, or Afrikaners).

But what followed was completely unexpected for the several hundred guests, me included, arrayed before the podium. Having commenced a prepared speech of suitable and forgettable politeness, Mandela took off his reading glasses midway through his courtesies and went vehemently off script. In altogether more memorable fashion, he launched a root-and-branch attack on the National Party, blaming it directly for the crime wave then engulfing the suburbs and townships of South Africa, and which had been a central theme of the recent local government elections in Johannesburg. His angry tone was reflected in his eyes, which seemed to focus directly on De Klerk, then serving alongside Mandela in the Government of National Unity (GNU). As the former president later wrote in his autobiography: ‘He worded [the attack] in such a manner that it was clear that he had targeted me personally as leader of the party.’

This somewhat dampened the bonhomie of the night, but we all duly retreated into the building for the banquet – all except Mandela, who had indicated he would have to leave before the meal began. It was only the next morning, when The Star newspaper splashed candid pictures across its pages, that South Africa learnt that Mandela’s dressing-down of De Klerk had continued outside on the pavement. The photographs showed the two joint Nobel Prize winners wagging fingers at each other – with an anxious-looking Minister of Mineral and Energy Affairs, Pik Botha, trying to intercede. This was a further reminder to the country that the relationship at the summit of political power was neither peaceful nor happy. In fact, De Klerk and the National Party’s presence in government would end, by their own hand, less than a year after the showdown that evening.

6 Hollard Street including the famous helipad from above (google maps)

The magnificent atrium of the building (The Heritage Portal)

The future of the building

21 years after this historic opening, many readers will be asking themselves why South 32 made the decision to leave the landmark building. Knowing the firm's strong attachment to its history, it appears to be the simple case of not being able to utilise the huge amount of space the building offers. Word from the heritage community is that with the corporate changes over the last few years only a few floors of the building were actually being used making it difficult for top management to justify staying put.

It appears as though the building has been sold to a property firm and that the Gauteng Department of Education will be the new tenant. Assuming this is the case, the Department's employees can count themselves lucky to work in a magnificent building in such an historic part of the city. The entire heritage community hopes it will treasure the building as much as South 32 and its predecessors have done.

* The recollection has been shortened for the purposes of this article.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.