Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the previous installment of the History of Southern African Railways series Peter Ball explored the politics and economics of the Benguela Railway. In this edition he heads east and unpacks the complexities of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway.

On the 14th July 1976 the Chinese officially handed over the TAN-ZAM Railway to the Governments of Tanzania and Zambia. It had taken just five years to build and its commissioning would change the pattern of economic dependencies in the region.

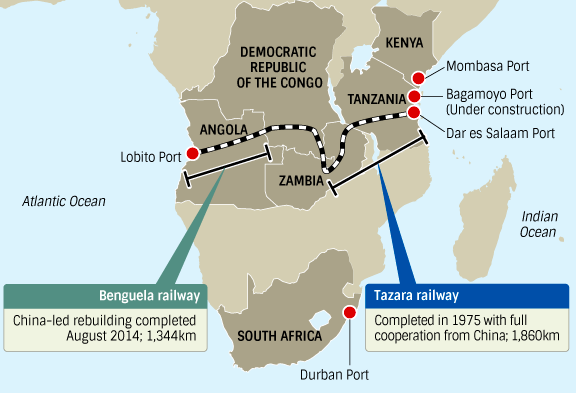

Officially known as the Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) the 1 860 km (1 156 miles) long rail link between the Copperbelt and the port of Dar es Salaam, has long been dubbed the “Uhuru” or Freedom Railway, a reference to the fact that it was built to lessen Zambia’s heavy economic reliance on Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa.

Tazara Railway on the right

If we go back fifty five years, to 1960, the political map of Africa was totally different to what it is today and large parts of the continent were still under the colonial rule of the European powers of Britain, Belgium, France and Portugal. Independence movements were however agitating just as they had in Asia fifteen years before, at the ending of the Second World War.

At the beginning of the 1960’s Zambia was still called Northern Rhodesia and with Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland formed the Central African Federation, a quasi dominion within the British Commonwealth, whose white leaders hoped for full dominion status. This hope was dashed with the rise of African Nationalism, started by Dr Kwame Nkrumah in the Gold Coast, which gained its independence, as Ghana, on the 6th March 1957. He in turn was ousted in an army coup in 1966, whilst away on a visit to Peking.

The “Swinging Sixties” usually refers to the music emanating from Britain as sung by the Beatles and Rolling Stones, et al, but it could equally describe the swing in Britain’s attitude to her colonies, as one by one they were given independence (between 1957 and 1968). It was also the decade where the Cold War between the West and Russia (and her satellites) was at its most perilous.

The seeds of the “Uhuru” railway were sown when the then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Harold Macmillan made his famous “Winds of Change” speech to the South African Parliament on the 3rd February 1960, in Cape Town. He spoke frankly for 40 minutes and left no doubt in the minds of his listeners that African Nationalism was here to stay and that Britain’s African colonies would be given independence; events which soon transpired were a direct outcome of the speech, i.e. Britain’s policy shift in colonial affairs (under direct pressure from USA to de-colonise). At the end of 1963 the Central African Federation was dissolved (it was already falling apart by 1961) and Britain’s policy of “No Independence Before Majority Rule (NIBMAR)” meant that Southern Rhodesia (the driving force of the CAF) would have to comply and hand over power to its black majority. However Southern Rhodesia had been a self governing colony since 1923 (for 40 years) and had a well run economy and its white leadership, seeing the upheavals in Ghana, Algeria and the Congo, was loath to give up control of one of the best run economies in Africa. This sets the scene to the stand-off between Britain and her colony which ultimately led to Southern Rhodesia’s “Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI)”on 11th November 1965 which was based on the American declaration of independence of 1776. However, where America succeeded Rhodesia failed. At the time of UDI a comedian remarked that Rhodesia was “Surrey with a lunatic fringe on top”, a swipe at the Prime Minister Ian Smith and his Rhodesian Front Party.

MacMillan with Verwoerd during his visit to South Africa (Harold MacMillan - A Life in Pictures)

The reader may well ask, what has this all got to do with the building of a railway? The answer is that in 1964 the newly independent Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia) was tied economically to Southern Rhodesia and its main revenue earner, copper was exported by Rhodesian Railways southwards via the Victoria Falls bridge to the port of Beira, in Mozambique (a Portuguese province).

Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, the newly elected leader of Zambia was eager to lessen his economic dependence on the “White” south, which was in a strong position to influence the emergent country’s political choices. The Benguela Railway was a possible choice of a route for copper exports however it ran through Angola which was a Portuguese province that was fighting an escalating war of independence against colonial rule and that line was often closed as a result.

In 1964 Kaunda commissioned the World Bank to investigate the possibility of building a railway through Tanzania (formerly Tanganyika, which had gained independence in 1961) to the port of Dar es Salaam, on the east coast of Africa. The Bank’s report found that the building of the railway was not an economic proposition and suggested building a highway instead. This did not satisfy Kaunda and he approached the western democracies to finance and execute the project. Only Britain and Canada showed an interest and followed up with an aerial survey jointly undertaken and although the scheme was considered to be viable from an engineering standpoint (as reported in July 1966), it failed to gain sufficient financial backing. This was a blow to Kaunda, who was a West leaning moderate, but things had already come to a head over Rhodesian UDI the previous year and Zambia was forced to choose its stance, which was to become a front line state against the White supremacists to the south. The consequences, both economically and politically were to drive Zambia into the same camp as Tanzania, which under the rule of Julius Nyerere, lent towards communism and Chairman Mao.

Having failed to get a donor from the West, President Kaunda travelled to Peking (now Beijing) during June 1967 and received an offer from the Chinese to finance and build the TAN-ZAM Railway as a “turnkey project”. Zambian and Tanzanian Ministers flew to Peking and on the 5th September 1967 and formally signed a deal with the Chinese.

Few developmental projects have been so highly politically charged as the TAN-ZAM Railway as the international repercussions reverberated far beyond the borders of the two states concerned. White controlled southern Africa and the West saw the project as an attempt by China to subvert southern and central Africa. However it has never been proven that this was China’s aim, although it was claimed in certain Portuguese circles that Chinese railway officials were responsible for training sections of “Frelimo”, which was fighting against the Portuguese army in Mozambique, from base camps in southern Tanzania. In fact the Chinese did not seek immediate political gain out of the venture - the third largest in Africa after the Aswan Dam (Egypt) and the Volta Dam (Ghana).

By not making any political demands China gained considerable prestige and goodwill in Africa and when the project was completed two years ahead of schedule its prestige was further enhanced. Peking called the Railway a “Rainbow of Friendship” and it helped to align Tanzania and Zambia with China in the Third World bloc.

The Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority was established in March 1968, with survey and design work being carried out by the Chinese between October 1968 and May 1970. In July 1970 China offered an interest free loan of Yaun 988 million (around US $ 500 million) to be repaid in thirty years, which would cover the costs of construction, supporting infrastructure, motive power, rolling stock and staff training.

From the outset it was decided to build the line to the Cape Gauge of 1 067 mm (3’-6”) in order to allow through working of rolling stock to the existing Zambian system (ex. Rhodesian Railways), whereas the existing Tanzanian railways ran on the Metre Gauge (3’-3”), a legacy of German colonial rule before the First World War. The closeness of the two gauges precluded trains running on a section of dual gauge track, which meant that the existing line out of Dar es Salaam going westwards, could not be utilised. Interestingly the East African Railways, who controlled the railways of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania from 1948 to 1975, intended to convert to the Cape Gauge and there was provision for this in the design of the famous “59” class Garratt locomotives of 1955, however cost constraints after independence from Britain meant conversion would not be carried out.

The work was inaugurated on 26th October 1970 and track laying was commenced from Dar es Salaam (DAR) and within a year had reached Mlimba at a distance of 500 km from DAR. West of Mlimba the terrain became mountainous and more difficult for railway construction and several tunnels and bridges were built in the next 152 km stretch to Makambako (652 km from DAR). The Zambian border at Tunduma (970 km from DAR - roughly half way) was reached by August 1973 and the connection to the Zambian Railways was made at Kapiri Mposhi (1860 km from DAR) by June 1975. Kapiri Mposhi was then a small village between Kabwe (Broken Hill) and Ndola.

The line was (and still is) a tribute to Chinese engineering skill and in the mountains of southern Tanzania where the railway climbed 1 830 metres (6 000 feet) and thus was the most difficult section, 45 000 African and 15 000 Chinese laboured, slicing into hillsides, blasting tunnels and suspending bridges over ravines. Rumour was rife that the Chinese sent out a “Chang Gang” of convicts to serve their sentence doing hard labour building the railway, whether or not this was the case is still a matter of conjecture if you will an “Urban Legend”.

The completion of the railway came none to soon as landlocked Zambia’s traditional routes were effectively closed by the bush wars in both Angola and Rhodesia. The line had, at the time of its opening, a capacity to carry two million tons of freight in each direction per annum, however that was never attained as severe bottlenecks at Dar es Salaam were experienced.

During the railway’s nearly thirty nine years of operation, the line has never achieved the efficiency and volume of traffic that was hoped for. This has been due to many causes with poor maintenance practices being top of the list, with non availability of wagons, derailments and locomotive breakdowns being a common occurrence. One only has to go on line and look on “YouTube” and see films of journeys where a trip that is scheduled for 36 hours takes 50 hours, due to a breakdown.

Screenshot from a Tazara Rail Journey (Hein Dielissen)

With the passing of time competition, from both road and other rail lines, has caused a drastic decline in the volume of goods transported along the line, which in turn has caused TAZARA to run at a loss for the last ten years. This has led to talk of a split between the two shareholders, whereby each would in future operate and maintain its own stretch of line up to the border between them (at Tunduma). This is only speculation in the press but there could be some substance to it.

The political differences of the 1960’s, which made the building of the railway necessary (its “raison d’etre”) no longer exist, as the Apartheid era ended in 1994, and therefore the copper mines of the DRC and Zambia now have a choice as to which port they wish to use to ship their product to world markets. Zimbabwe has built a new cut off line, under private concession, between Bulawayo and Beit Bridge which avoids the old Cape to Cairo route through Botswana and therefore shortens the distance to South African ports notably Durban; this further exacerbates TAZARA’s problems.

The future of TAZARA is in the hands of the people that financed and built it in the first place - the Chinese. Their policy of infrastructure for raw materials is now in full swing across the African continent.

What will the next ten years bring to our region, economically and politically? Remembering that South Africa is the “brickette” in “BRICs”."

Further Reading

- “Africa’s Freedom Railway” by Prof Jamie Monson

- “China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants are Building a New Empire in Africa” by Howard French

References

- TAZARA posts on its web site (tazarasite.com)

- RAILWAYS Southern Africa: March 1977 “Accent on Conflict Part 1: Tanzam Railway" on pages 21, 22, 23 & 26

- “Atlas of the World’s Raillways” by Brian Hollingsworth

- “Railways of the Twentieth Century” by Geoffrey Freeman Allen

- “TRAINS – The Complete Book of Trains and Railways” edited by John Westwood

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.