Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

On a Saturday afternoon, after a morning spent in a similar manner, a man wearing black trousers, a black T shirt and cap, all offsetting his white hair and beard, is showing a group of tour guides around Newtown and Joburg centre city. He walks energetically and purposefully, one might even describe him as bulldoggish in the way he moves, and he recites the facts supporting the city’s revitalization. For three hours he demonstrates the renewal of Joburg. The visitors are stunned. Their pencils are never still; their cameras click away. They crane their necks, viewing this transformed city. What he doesn’t tell them is that were it not for him and some far sighted and dedicated colleagues and associates, our city, the repository of living memories, of history, of wonderful architecture, would be well nigh moribund and lost in irreversible decay. After the tour, Neil Fraser downs a quick beer and rushes off to another engagement.

Neil Fraser

I talk to Fraser, born in 1939, Executive Director of the Central Johannesburg Partnership, in his office situated in a magnificent reclaimed building in Market St. In the first decade of the Twentieth Century it was used by Natal Bank whose wrought copper logo remains inscribed on the marble front step. Fraser’s high ceilinged, comfortable office is where the bank manager or accountant once sat. It faces onto the old banking hall with its rich, wooden, tellers’ counter standing under the striking, moulded ceiling. There isn’t the slightest hint that the banking hall was ever subject to security precautions despite the threat of Johannesburg’s infamous Foster Gang. An Honorary Citizen of Baltimore certificate hangs among many memorabilia on his wall. Behind his desk chair hangs a two metre wide coloured photo panorama of Joburg’s downtown skyscrapers. Fraser thinks and talks fast. His face is impassive. A Scots background and years as a senior executive have taught him to camouflage his passionate intensity, but his life story gives him away.

Natal bank from above

Natal Bank Banking Hall (The Heritage Portal)

Fraser, a recovering workaholic, had no desire to come to Johannesburg. He displayed all the normal resistances shown by wine quaffing, mountain and sea loving dwellers of the Mother City. And it wasn’t as if he needed work stimulation or money. He was doing fine thank you, as Managing Director of Murray and Stewart’s building operations in Cape Town. But in 1985, his company, which had merged to become Murray and Roberts, finally prevailed and he moved. Thus, Johannesburg gained a lover and a champion; a man who not only enjoys being a citizen, but who has helped reclaim a centre city which, ten years ago, was fast sliding into ruination. But paradoxically, when he was offered the task of revitalizing Joburg, he turned it down. When he finally took the job he hated it! It was so different from managing a large enterprise. But then he grew to love it. What was it that changed?

Fraser grew up in Camps Bay, where today, several million Rand won’t buy you much in the property line. His parents managed the Camps Bay Hotel. He attended the local primary school, later went to Christian Brothers College and after his parents’ divorce, finished his schooling as a boarder at SACS. As a non-too-focused school leaver, he toyed with the idea of hotel keeping but was persuaded to start Land Surveying at UCT which he hated. He changed to Quantity Surveying which he enjoyed and which, he realised, with its grounding in accounting and construction disciplines, promised broad career prospects. His career was indeed extensive; ultimately, he was to become expert in managing urban renewal, an intriguing, late twentieth century discipline, necessary as so many mature cities sought to free themselves from the grip of decay.

He served his articles in a practice where he at first earned nine pounds, ten shillings a month. Small as the sum was, it was helpful as he was paying his own way. His boss was an ‘old time professional with no people skills,’ whose view of the ideal career was a steady plod through the ranks to an eventual but distant, partnership. ‘Old school professional nonsense,’ as Fraser calls it. Boss was horrified when Fraser, shortly after qualifying, left the practice to enter the more exciting world of construction. The old timer went so far as to threaten Fraser with professional blackballing. ‘He promised that he’d make sure I wouldn’t get another job in the profession, that I’d be tainted forever more. He upset me.’

During the following two years spent with Murray and Stewart Construction, Fraser met a 35 year old property developer with whom he developed a close relationship. The man, deciding to undertake his own contracting, invited Fraser to join him in the Geneva Construction company. Fraser set to with his characteristic gusto. ‘We built the business into a force in Cape Town. Soon we were engaged on major projects. We became well known for two things: integrity and hands on involvement. I ended up as Managing Director in my late twenties.’

Geneva Construction benefited from the advice of the owner’s friend, a smart marketing man. Fraser continues, ‘Up to that time, in the sixties, construction companies hardly bothered to signal what they did. For instance, Murray & Stewart what? He persuaded us to erect signboards saying: Geneva is Building. The slogan became well known. On a major city site we placed our striking, unusually worded signs, so that people would see them when they drove to work and also when they drove home. All was going well when a tragic event changed our lives!

‘The owner of the company was a well known and admired Cape Town personality. Wealthy, divorced, with two daughters, he remarried but when he discovered his new wife was having an affair he killed her in passion. In court he never mentioned the affair. He was found guilty of murder and sentenced to twelve years in Pretoria Central. It was suggested that had it not been for his reputation and exceptional presence he would have received life, or even a death sentence. After five years he was released with the proviso that he leave South Africa, after which he settled in London where he died in 2003.’

So where did that leave Neil Fraser? Once the owner was jailed, the other partners lost their appetite for continuing. Fraser experienced several tough years holding things together until in 1973, the business was sold to Murray and Stewart and which included an employment offer. ‘I didn’t want to go back. M & S had become a giant, and anyway, I was smarting. I’d put my life and soul into Geneva. We employed people who looked to me for their security. I thought that selling was solely my responsibility; quite dumb really. My first wife convinced me to go back. I thought I could hide away somewhere while regaining my confidence, but they threw me in at the deep end.

‘My new boss told me that my job was “to tune into other people’s dreams.” It was a matter of getting wind of projects before developers went to tender; to link the developer and our construction team. The job gave me the chance to become involved in huge, exciting projects. I traveled extensively, studying international trends. The organization loaded me with work. They showed no interest in my other life; quite happy with me leading an unbalanced existence. Operating in that ethos, I developed a huge propensity for long hours and intense work. I became enmeshed in the corporate game; receiving many promotions. In short, I became a workaholic. It led to my divorce. I was never home.

‘Des Baker, M & S’s MD, was a model for me. He displayed enormous drive, energy and vision and suffered from the worst case of workaholism I’ve ever seen. He’d call me out of sleep at two am. He smoked and drank like a trooper. My worst fate was the late afternoon chat. I seldom got home, a bottle of Scotch the worse, before two or three in the morning. He’d want to know why he hadn’t seen my car in its bay on Saturday mornings? Trouble was, I enjoyed the pace, and I’m not quite free from it yet.

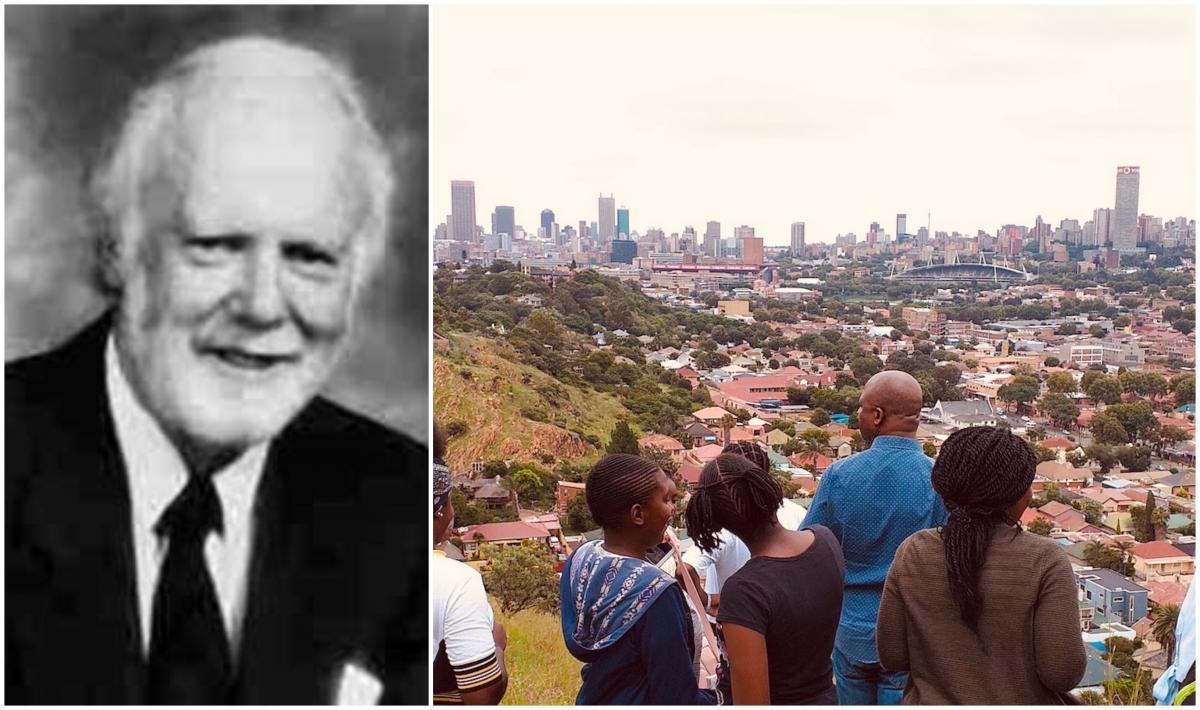

As with other addicts, Fraser eventually found it necessary to confront his demons. ‘Although I still work very, very hard, I try to maintain a better balance. Up to 1992 when I started CJP, I was totally unbalanced. I worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. I had no religious belief in those days. My family came a very poor second. I experienced a major challenge in the early 1990s which resulted in my becoming a committed Christian. I do as much in the church as possible including lay preaching and devoting time to a Christian think-tank. I moved to the conviction that my most important priority is my relationship with God. The second one is my relationship with my wife and family, and my work comes third. Hazel, my present wife and I, have a very good relationship. She’s very understanding. She knew me before we married; she saw how I worked, so she came into it with her eyes open. She acknowledges my two mistresses – my work and the city of Johannesburg. She’ll pull me up now and then, ”Hey, you haven’t spoken to me for two weeks!” no, no, not quite as bad as that.’ [Laughs]

The City of Joburg, one of Fraser's mistresses (The Heritage Portal)

Is it all work? Fraser pretends that it isn’t. ‘Relaxation, ja, I love gardening, I love cooking and reading; I just don’t have enough time for any of them. I have eclectic tastes in reading: thrillers, spy stories, but my main reading now is about the history of Africa, the real history not the white man’s version. I read magazines from all over and usually have 12 to 15 books next to my bed. I usually read between half past one and four in the morning. It depends how I feel when I wake, as to which one I pick up. I sleep like a log for four or five hours then my mind takes over and I wake up.’

Fraser’s Joburg based career began in the eighties. After serving as a Divisional Director on the board of Murray & Roberts Construction at company head office in Bedfordview from 1985 to 1988, he was seconded to the Building Industries Federation for a year ‘to sort out their problems. The sorting out process took three years longer than I expected. I enjoyed being out of corporate life, but I did not want to stay at BIFSA. It was a long time to be away from Murray & Roberts. I thought it was time to go on my own. I took the earliest possible retirement option and started my own consultancy,’

The consultancy was not to last long. Fraser didn’t take easily to the task. ‘I started in August 1992 and for the first year, I hated it. I didn’t know what I was doing: a new world, new people, definitely not enjoyable. I hung in because something stirred. It was a time of listening: to property owners, store keepers, hawkers, apartment dwellers. After a year, after overseas study visits, I discovered a brotherhood, a sisterhood of private sector urbanists who are nuts about cities. It’s an international phenomenon. Through contact with these private sector people, I began to be challenged by the query, what drives city revitalization? The sheer size of the problem was incredibly challenging. Johannesburg was such a mess. Like David viewing Goliath, I took heart by reflecting “what a big target!”

Fraser asserts that for effective city renewal, several essential factors must combine. These, he says, follow principles that have emerged from world wide experience. The first, he claims, is a local authority with political will and muscle. If a city is being reclaimed the authority will inevitably be dealing with degradation linked to urban poverty. Is the authority tough enough to move people if necessary; tough enough to confront slumlords and demand responsible behaviour; tough enough to start programmes in the face of political censure and perhaps a scathing press? Experience elsewhere has show that local authorities are generally not effective in delivery issues. Thus, an independent projects delivery body becomes another essential in the mix. In Joburg, this role is fulfilled by the Johannesburg Development Agency [JDA]. Then, local businesses and property owners must be committed to improving the environment and to release funds therefor. The last essential role, that which Fraser’s own organization [CJP] provides, is that of catalyst, bringing the parties together, oiling relationships, establishing management and communications structures. The CJP also educates the players by organizing overseas study tours and arranging visits by international experts.

After his early struggles, Fraser noted his changed work world, ‘I discovered that managing reclamation is a complex animal without formal command and control mechanisms; quite unlike the hierarchy of business management. It’s a working with, a cooperative situation where people add value to one another. It primarily draws on human skills; negotiation, cajoling, compromise, manipulation, great diplomacy. I found that this new world appealed to me, so much broader than corporate life.

‘I discovered one of the prime examples of renewal in New York. Their work started in 1980, when it was down on its knees: insolvent, crime ridden. A huge amount of work was done by urbanists to get NY back on track. Districts such as Wall Street, Times Square, 32nd Street Fashion District, Union Square, those were prime examples of urban renewal. I found much inspiration there.

New York Skyline (Roy Cotton)

Today’s model is Washington DC. My friend Richard Bradley, who occupies a job similar to mine, has done a magnificent job. Washington’s CBD has undergone a huge resurgence; so has the State Street precinct in Chicago.

Fraser tells us that CJP’s work in Newtown and in the Fashion district in Pritchard, President and Market Streets east still focuses on housekeeping and safety issues which are no longer important problems, but also addresses ‘the challenge of how we develop business in these areas? Performance and tourist businesses in Newtown, history, plays, music, dance, art and craft sales, and garment manufacture in the east.’

Museum Africa, Newtown from above (The Heritage Portal)

Some years ago Graeme Reid [Chief Executive of the JDA] and I went to look at Californian examples of development agencies. We really got the basic ideas from Los Angeles, Long Beach and San Antonio. Business supported the idea strongly.

At first Fraser wondered whether Joburg Council would offer significant help? ‘Until about 2000, the city, that is the Council, wasn’t coming to the party. They were making all the right noises but only lip service was paid to the inner city. It wasn’t really until Amos Masondo was appointed as executive mayor that things began to happen. He’s the first Mayor to see the inner city as a priority. That’s made a huge difference. I hope Masondo remains the Mayor and I hope he maintains the inner city priority. From being a reluctant partner the Council is now the major partner.

Metro Centre Johannesburg, the home of local government (The Heritage Portal)

‘I’m passionate about this job and I’m able to channel my energy into it. I apply a long term vision. I’m reasonably diplomatic which enables me to work with all kinds of people. I’ve made it a point to remain a-everything, apolitical, acentric, so I don’t tramp on people’s toes. I have strong views but I take into account others' views as well. This is the best job I’ve ever had; the most frustrating and the most fulfilling!’ Fraser says a hurried goodbye and rushes off to another meeting.

I thought the story sort of conveniently ended there, but because the book took many months to write, I found, during the editing stage, that it had not described the dynamic and fast moving Neil Fraser’s latest career move. He explains it thus: ‘At the end of 2004, I realized with horror that I had been heading the CJP for some twelve years. Why with horror? I guess I remembered a lecturer who made a great impression on me with his findings on Chief Executive Effectiveness. This was back in the seventies when I was doing some post grad work at UCT. Teddy Weinshall, [then in his late 60s/early 70s] Prof. of Business Science at Tel Aviv University had spent his life researching the largest single impact on the profitability of a company. He had come to the conclusion that it related directly to the length of time a CEO held that position! His research showed that any one individual could only remain really effective for an average of seven years at which stage he should be fired, retired or promoted. You may have noted that the Israeli army has its commanding officers in place for only relatively short number of years. I understand that this was due to Weinshall’s influence.

‘I was beginning to feel that I was getting jaded, not adding as much value to the CJP and that the business could do with a lift from a new perspective. So, having given all concerned notice, I launched out from March 2005 into an urban consultancy practice with offices in centre city and Rosebank. With Katherine Cox as my business partner, I’m still totally committed to the city and most of our work continues to be inner city related.’ I’m delighted that Fraser’s move has not caused him to relinquish Citichat.

In the March 12th, 2006, Sunday Times Metro, a headline reads: A 21st Century Goldmine. The article below tells how Johannesburg’s ‘inner city is booming and developers say there is more than R3 billion invested to prove it.’ A sister article in the same issue features property tycoon Alfonso Botha’s centre city penthouse developments, some priced for as much as R30 million. I ask Neil Fraser how he feels? His tone of voice suggests he’s not crazy about it. I gather he’d rather see the city as home to many rather than a rich man’s toy. ‘I worry that prices will become artificially high,’ he says, but adds that of course he’s highly gratified at the turnaround in a city centre that a mere decade ago was looking and smelling like a cadaver.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.