Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Killarney is one of the great historic suburbs of Johannesburg. With its majestic buildings from different eras, there is a great case for it to be declared a heritage area. The article below, written by journalist Lucille Davie, is packed with fascinating details on the people, history and architecture of a majestic neighbourhood. The piece was originally published on the City of Joburg's website on 18 January 2012. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

Running a bath in a flat in Gleneagles is more than just filling up a tub – the hot water goes via a stainless steel towel rack attached to the wall, heating it before the water reaches the bath.

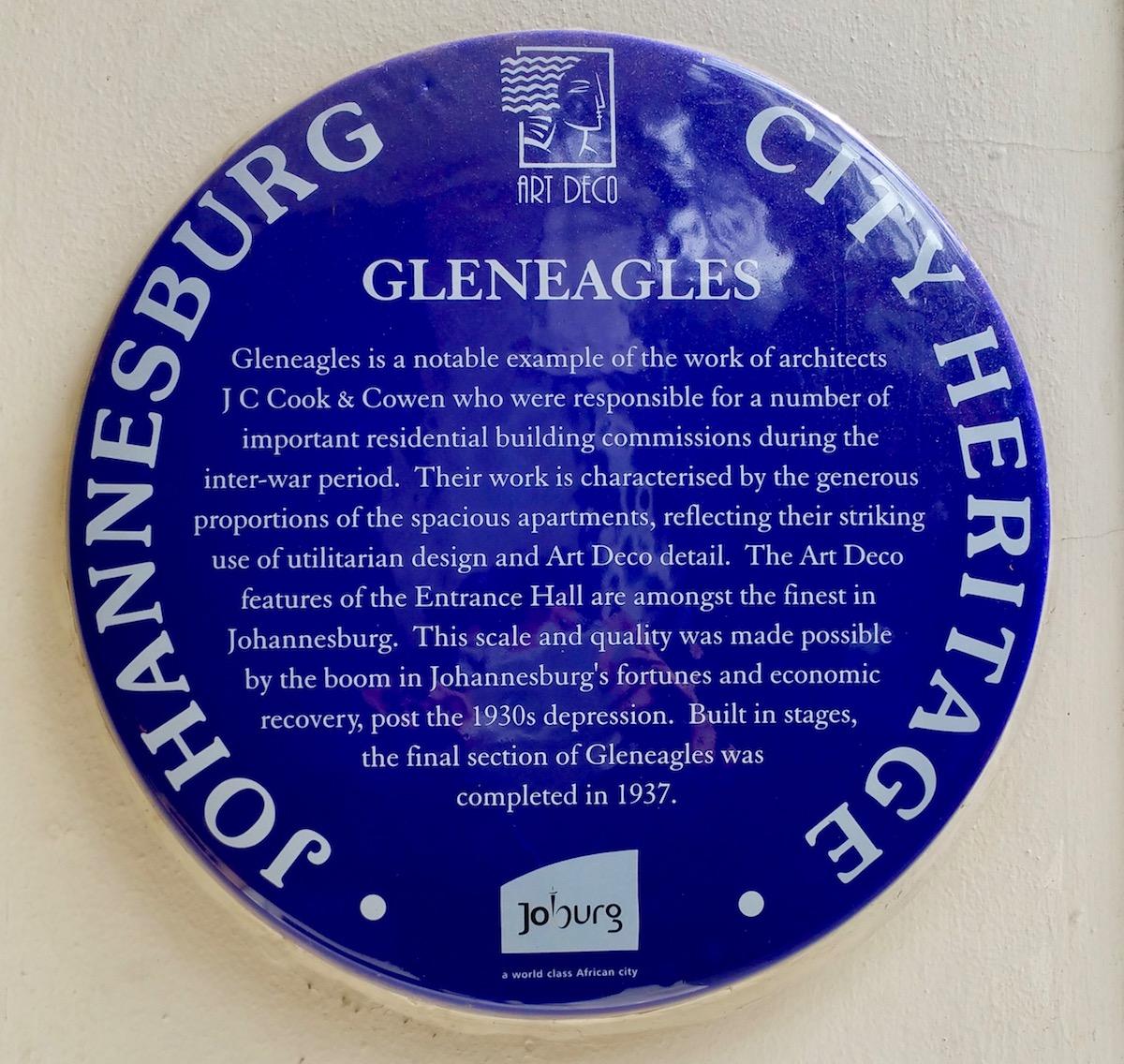

Gleneagles, an art deco building in Killarney, has just been given a blue and white Egoli Heritage Foundation heritage plaque. It is one of several art deco blocks in the suburb – Mentone Court, Killarney Mansions and Daventry Court are other outstanding examples of the style.

Gleneagles Blue Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Gleneagles (The Heritage Portal)

Besides the towel rack, Gleneagles bathrooms make bathing a stylish affair: a decorative metal laundry basket alongside the rack is tucked neatly into the wall. The bath itself, made of iron, has three raised horizontal lines running its length, in typical art deco style. One-of-a-kind bathroom floor tiles, in a small black and white knotted pattern, match the row of black tiles above the white-tiled walls.

The 76 flats are replete with other finely crafted finishes: brass light fittings, decorative steel door handles, parquet and strip flooring, rare mottled glass in the interleading corridor doors, three raised horizontal lines atop the lift shaft columns, a garbage shoot running down the fire escape stairs, but no longer operative. Hot water was originally supplied to residents via a coal boiler in the parking basement, now supplemented with a gas boiler.

The foyers of art deco buildings often have features that make a bold statement – and Gleneagles is no exception with its gleaming, striking brass door, sparkling granite floors and black marble walls with aluminium trim, subtle recessed lighting along the ceiling, an alcove with a wall of metal post boxes, and the original angular wooden furniture in the foyer. An aluminium model of the north facade of Gleneagles rests on the central wall, beautifully executed.

Gleneagles Foyer (The Heritage Portal)

Retired advocate Ruth Kuper has lived in Gleneagles for 48 years. She has a fourth floor north-facing flat, bursting with books and art. She has combined the original lounge and dining room into a single large, elegant room, with semi-circular windows on one end. Two spacious bedrooms – one converted into a dining room – together with a compact kitchen and bathroom, give her 184m2 of comfortable space.

She shares her flat with four affable cats – Tarzan, Jane, Romeo and Junior (“If I’d named him Juliet he would have been cross with me”).

Art deco

Art deco hit South Africa a decade later than it took off in the rest of the world. The US and Europe experienced the art deco rush in the 1920s, with its eclectic style capturing industrial modernity and, in contrast, fantasy.

The depression of 1929 slowed things, but South Africa was buoyed by gold at the time and Johannesburg experienced a boom in the 1930s, with a splurge of new buildings going up in the city.

London House, Howard House and Main House Johannesburg. All built during the 1930s boom. (The Heritage Portal)

The art movement was inspired by several global events: in 1922, Tutankhamen’s tomb was discovered and the world marvelled at his treasures. Soon elements of Egyptian art – the decorative squareness of the head decoration, the vertical lines suggested by the figures – appeared in architecture.

Other events in the 1920s and 1930s heralded a new world: the land speed record was broken, air travel took off, luxury passenger liners with their sleek metallic lines took to the seas, movies and the cinema introduced a new glamour. Colonial and classical architecture were taking a back seat – the new style incorporating sleekness and decorative flourishes was blooming. Dance, jewellery and furniture too reflected this speediness and zest.

Springs Fire Station. A heritage site and art deco landmark. (The Heritage Portal)

Gleneagles was completed in 1937 by architects JC Cook and M Cowen. Its semi-circular bay windows and rounded edges softening the corners of its H-shape, and decorative horizontal lines along its roof line are typical art deco.

Many of the rounded balconies have been enclosed, steel window frames have been replaced with aluminium, and some corridors have been glassed. Interiors of flats have also been altered, making them more practical for modern living.

Conservation architect Herbert Prins, who lives in the nearby Mentone Court, says that enclosing balconies does not necessarily detract from the heritage status of a building. “It is an accepted principle that a building can’t be a museum, the building has to function.” The guiding rule is whether the alteration is reversible or not.

Heritage is expected to evolve in layers. “Provided the layers are compatible and enhance the building,” he adds.

In the country

Kuper remembers Killarney being almost in the country when she moved into the suburb in 1963. “It was a very rural feel.” There was a swimming pool, tennis courts, and plenty of open green space – the Killarney Country Club stretched right up into the suburb before it retreated northwards when the M1 was built.

Killarney is a small suburb, its streets edged by tall jacaranda and oak trees, with several dozen blocks of flats, most in a modernist 1950s and 60s style. It is sliced in half by the M1 North, and bounded in the south by The Wilds. The Killarney Country Club runs north from Riviera Road in the suburb of Riviera, along the western edge of the M1. Although small, Killarney has an elegant park at its heart, with a row of mature jacaranda trees running through it.

“Killarney is a very interesting area because it has a variety of buildings, dating back to Whitehall, a colonial building, then art deco, then bad buildings, which on the whole are of a reasonable calibre,” says Prins.

Whitehall Court (The Heritage Portal)

An anomaly is the single house in the suburb, in Third Street, probably built in the late 1930s, in art deco style. Killarney was created as a suburb of high-end blocks of flats but this house was built by Nat Stein, who owned a number of blocks in the suburb, for his brother-in-law, who supervised the building of those blocks.

“It is pretty unique in Johannesburg and South Africa – a high income flatland.” Prins feels that the suburb warrants being proclaimed a heritage area.

Built as a high income suburb, a retreat for empty nesters and retired people, its demographics are changing. With a mosque across the freeway in Houghton, and another under construction, it has attracted Muslim families. The newly refurbished cinema in the shopping centre is Indian-owned, and at least half of its screenings are Bollywood movies.

It is no longer a suburb for “the newly wed and nearly dead”, says Kuper. Young couples and professionals are moving in.

Famous people

Over the years, Kuper has shared Gleneagles with several famous and not-so-famous people. Dolly Maisels was the aunt of the well-known and respected advocate Israel “Issie” Aaron Maisels, an advocate for more than 60 years. She was the daughter of Sammy Marks, the entrepreneur who had interests in manufacturing, coal mining and agriculture, among others.

Another resident was the highly respected advocate, Harry Morris, who defended the notorious Daisy de Melker, who was charged with poisoning two husbands but convicted of poisoning her son. She was hanged in Pretoria in 1932.

“She is believed to have murdered another seven people,” says Kuper. Four of those were possibly her young children from her first marriage, she suggests.

Dr Vic Todes, a retired radiologist, used to accompany the late politician and human rights stalwart Helen Suzman on visits to Robben Island, where he took x-rays of political prisoners. He visited the island several times but doesn’t recall who exactly he x-rayed. He has lived in Gleneagles for 25 years.

The late Thelma Gutsche also lived in Gleneagles. She was born in Somerset West and was a scholar, historian and film writer. She was a founding member and trustee of the Association of Friends of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), according to sahistory.org.za.

She was also a founding member of the Simon van der Stel Foundation, set up to conserve and restore buildings of historical and architectural importance. She wrote a biography of Florence Phillips, the woman who was the brainchild behind the JAG, called No Ordinary Woman: the Life and Times of Florence Phillips.

Kuper’s uncle, the late Philip Hesselson, also lived in Gleneagles. In 1937, he flew a single engine plane from Johannesburg to London. “He did so to participate in a competition for the longest distance flight ending in London. He it in 300-mile hops, his only aids being a compass and a map,” explains Kuper. He won the competition and was awarded the trophy by Amy Johnson, the pioneering British aviator. The competitor who came second flew from Liverpool to London, says Kuper. She has the handsome trophy her uncle received as his prize.

The spritely and engaging 91-year-old Zelda Margo is a friend of Kuper’s in Gleneagles. Her husband, Harry, was a prisoner of war in WW2, and was reported missing in action, then confirmed dead in action, the ship he was in having been torpedoed in the Mediterranean. His family mourned his death but they were in for a surprise – he didn’t perish and had been held as a prisoner of war in Italy. When he was released he returned home to greet his astonished family. He died 18 months ago at the age of 94.

Killarney residents

Killarney can boast other famous residents. One is eighty-one-year-old Amina Cachalia, anti-apartheid activist and the first treasurer of the Federation of South Africa Women, an organisation representing South African women working for equal opportunities and rights for all women, regardless of race or colour.

In November 1963, she was banned for five years and her husband was placed under house arrest. After the ban expired she was served with two more banning orders, in total 15 years. Later she was involved in the formation of the United Democratic Front, a mass movement that helped topple apartheid. In 1994, she was offered an ambassadorship, which she declined.

The prolific writer, academic and literary critic, Stephen Gray, also lives in Killarney. He has written novels, essays, plays and poetry, and has received several awards. He has published two biographies of Herman Charles Bosman.

The inventor of Chappies bubble gum, the late Arthur Ginsburg, lived in Killarney until his death five years ago (click here to read about the Chappies story).

Arthur Ginsberg

History

The suburb of Killarney was originally part of the vast Braamfontein farm. In 1899, the eastern section was sold by the Houghton Estate Gold Mining Company to William Cook, who gave it the name Killarney, according to Naomi and Reuben Muskier in A Concise Historical Dictionary of Greater Johannesburg.

Cook was an Irishman and named the farm after Killarney in Ireland, where his wife Jessie Olive Scrooby was born, indicates The Joburg Book.

In 1905, Isadore William Schlesinger, an American entrepreneur and financier, bought the farm. In 1908, according to Anna Smith in Johannesburg Street Names, Schlesinger’s company, the African Realty Trust, advertised the Killarney Township as having “a garden, an orchard, a vineyard, an orangery, a shrubbery, a pinery, a paradise, a picture spot, a health resort, a township and a home”.

Among many other enterprises, Schlesinger was the founder of African Theatres and Film Trusts and built a film studio in Killarney, on the site of the present Killarney Shopping Mall. The studio was responsible for the popular newsreel African Mirror and feature films like The Symbol of Sacrifice, an account of the Zulu war of 1879.

Old photo of the Killarney Film Studios

Schlesinger’s company produced 43 movies between 1916 and 1922. “By the 1930s, it was producing early sound films, making film advertisements and creating the country’s first tourism films,” according to The Joburg Book.

Schlesinger built the grand three-storey mansion Whitehall in 1924, in colonial style, where he had the second floor as his living quarters. The rest of the building was used as his offices. Whitehall was later converted to luxury apartments. He died in 1949, and a decade later his son sold his film company to 20th Century Fox.

Old photo of Whitehall Court (South African Builder Magazine)

Killarney Country Club

Schlesinger oversaw the building of the Transvaal Automobile Club (TAC) in 1916 in Killarney. Jews were excluded from the Rand Club and the Johannesburg Country Club, so the TAC was built, with its own exclusivity – you had to have an automobile to qualify for membership.

According to the Killarney Country Club website, the TAC was founded originally to promote “automobilism” in 1908, which included the “compilation of road maps, organising hill climbs and campaigning against the prevailing speed limit of ten miles an hour within a radius of two miles from the Rissik Street Post Office”.

TAC members on a weekend trip to Potchefstroom (Potchefstroom Museum)

“The big motoring event of the Twenties was the Court-Treatt motor expedition from Cape Town to Cairo, a distance of 12 377 miles, which took sixteen months to complete, with the leading car carrying the TAC badge throughout.”

But the club wasn’t just for those driving cars. Its first bowling green was laid in Killarney in 1917, followed by badminton courts and croquet lawns. In 1926, squash and tennis courts were built, then a swimming pool, followed by the first ten-pin skittle alley in the Transvaal, which was used until 1953. The golf course, its southerly border in Killarney, was opened in 1929.

By 1930, the automobile functions were handed over to the Automobile Association for the “furthering of motoring interests in the Transvaal”, and the club became known as the Killarney Country Club. “Thus ended a memorable era in the history of the Club, leaving only the name to remind us of those early motoring days.”

In 1950, the African Realty Trust wanted portions of the southern end of the golf club for development – in 1961, the present shopping mall was opened. This was the push the club needed to buy the rest of the land from the trust and in 1957 this happened. But in 1965 the club had to give up some of its land to the city council for the building of the M1

In 1970, the city and the club reached agreement on a 50-year lease on 63ha of ground between Riveira Road in Killarney and Melrose Street Extension in Melrose until the year 2020. The lease was later extended to mid-2040.

The old clubhouse at the top of 2nd Avenue was demolished and a new clubhouse built in Fifth Street in Riviera, opened in 1970. The Killarney Village, a set of townhouses, now occupies the site of the old clubhouse.

The Egoli Heritage Foundation is considering heritage plaques for the other art deco buildings in Killarney.

Daventry Court Killarney (Boris Gorelik)

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.