Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is almost inconceivable to think the South African Air Force (SAAF) was established when T. E. Lawrence was still working on his much acclaimed biographical Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a history of the Arab Revolt during the First World War. Yet, this was indeed the case when Prime Minister Jan Smuts on 1 February 1920 appointed Lieutenant Colonel Sir Pierre van Ryneveld ‘Director of Air Services’ in the Union Defence Force (UDF). This date is now generally accepted as the founding date of the South African Air Force (SAAF), making it the second oldest independent air force in the world.

Ryneveld’s appointment was necessitated by the British Government’s generous offer in 1919 to each of the four self-governing dominions; Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand, of a substantial donation of aircraft and equipment to establish their own air forces.

This donation, subsequently known as the ‘Imperial Gift’ comprised a wide range of surplus war material, including 100 aeroplanes, complete with engines and spare engines, workshops, tenders, motor cars, motor cycles, and trailers; hangars for housing aeroplanes and stores; radio, and photographic equipment for two squadrons; tools to equip the SAAF mechanics and thousands of litres of paints, fuel, varnishes and dope. ‘’Dope’ is a plasticised lacquer that is applied to fabric-covered aircraft. It tightens and stiffens fabric stretched over airframes, which renders them airtight and weatherproof, increasing their durability and lifespan. The 100 aeroplanes included 48 De Havilland DH9, 30 Avro K and 22 SE5a aircraft.

Jan Smuts, having served as General Officer Commanding in the East African campaign and more recently in the British War Cabinet, immediately accepted this valuable offer. From past military experience, he realised ‘control of the air’ was as important as ‘command of the high seas’.

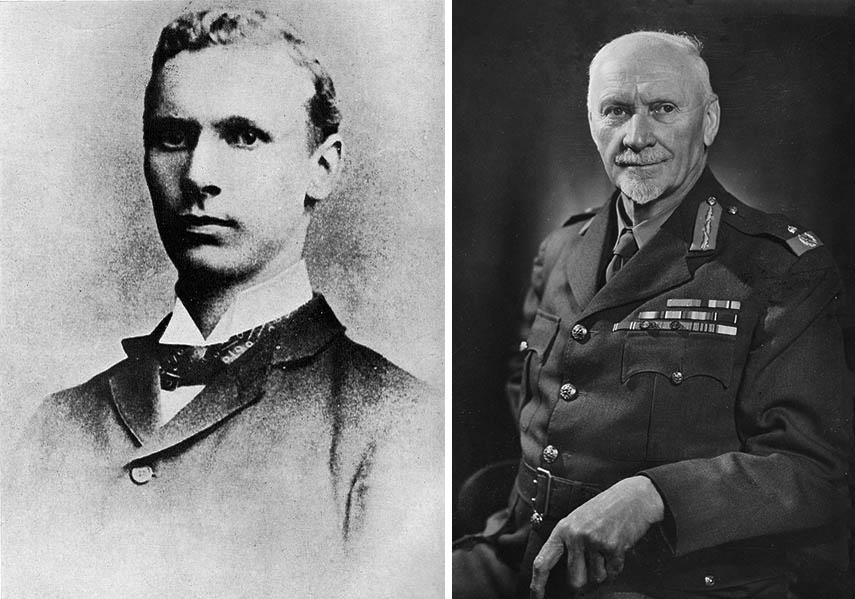

Young and old Smuts

A further 13 aeroplanes were subsequently added to the original Imperial Gift. They consisted of ten DH4 aeroplanes donated by the Overseas Club of London, one DH9 donated by the City of Birmingham and two BE2e aeroplanes previously used on a local air force recruiting tour.

For some reason and unlike the other dominions, the SAAF never applied the ‘Royal’ prefix. One can only assume it was deliberately omitted to molllify Afrikaner antagonism towards the Empire.

Jan Smuts is perhaps the only person in history who can rightfully claim to be instrumental in founding two air forces; the Royal Air Force and the SAAF.

Lloyd George divulged in his War Memoirs that Smuts, more perhaps than any man, has the right to be called the father of the Royal Air Force. In July 1917, the War Cabinet commissioned two of its members, the Prime Minister and Smuts to examine in consultation with various experts: (a) Home defence against air-raids and (b) the direction of the existing organisation for aerial operations. Lloyd George made it clear he left it to Smuts to direct the work of this select committee. In August 1917, the committee submitted its second report, recommending amongst others, the establishment of an Air Ministry and Air Staff as soon as possible and that arrangements should be made for amalgamating the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps (RFC).

War Memoirs by Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922

By April 1918, these two air services had been amalgamated to create the Royal Air Force, the world’s first independent air force.

South Africa was fortunate to have two exceptional air force officers in Pierre Van Ryneveld and Kenneth van der Spuy, to oversee the successful establishment of the SAAF. Van Ryneveld (1891 – 1972) obtained his BA degree at the University of the Cape of Good Hope in 1909 at the age of eighteen and later his BSc at the Imperial College, University of London. At the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Royal North Lancashire Regiment but soon transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, serving with distinction in the Middle East and on the Western Front. His courage and outstanding leadership earned him a DSO and the MC.

General Pierre van Ryneveld (via Pilots Post)

On 4 February 1920, Wing Commander Pierre van Ryneveld and Flight Lieutenant Quintin Brand set out from London’s Brooklands airfield to South Africa to pioneer the first trans-Africa flight (click here to read the full history of this historic flight). The Mediterranean crossing took 11 hours in a Vickers Vimy (the Silver Queen). Their first forced landing was in Wadi Halfa in the Sudan. The plane was badly damaged and a second Vimy (the Silver Queen II) was delivered 11 days later. After repairs conducted at the Heliopolis airfield in Cairo, the duo and their accompanying two air mechanics flew due south.

On 6 March 1920, the Silver Queen II crashed while attempting to take off from Bulawayo. A vast crowd gathered to welcome the flight and the Bulawayo municipality declared it a public holiday. Van Ryneveld later admitted that the fuel load of 350 gallons was probably too hefty for take-off from this high-altitude field. Amazingly none of the four on board were injured. An onboard ‘good luck’ kitten apparently also survived the crash. It seemed to confirm the theory that in low-speed accidents large wooden airframes absorb much of the impact.

One of the DH9 aeroplanes from the Imperial Gift package was hastily assembled in Pretoria and flown to Bulawayo, to be used by the two pilots to resume their journey, sans the air mechanics and presumably the kitten. This aeroplane, the ‘Voortrekker’, took off from Bulawayo on 17 March and made the first stop-over at the airstrip in Silverton (now on the University of Pretoria’s Hillcrest Campus). On 20 March they landed at Youngsfield in Wynberg, Cape Town. Both men were subsequently knighted for this pioneering flying feat.

Monument commemorating Van Ryneveld and Brand’s epic flight at the University of Pretoria’s Hillcrest Campus (Helene Potgieter)

It is said of Van Ryneveld that he possessed a brilliant brain, combined with a forceful personality that brooked little opposition. In 1933, he was promoted to Chief of General Staff of the Union Defence Force, before retiring in 1945.

Van Ryneveld’s deputy, Kenneth van der Spuy (1892 – 1991) possibly had an even more adventurous career. Commencing his initial military flight training near Alexanderfontein in Kimberley, he and five other South African student pilots were selected for further training with the RFC in the UK. In 1915 he was recalled to the Union to serve in the German South West African campaign, and then in the East African one.

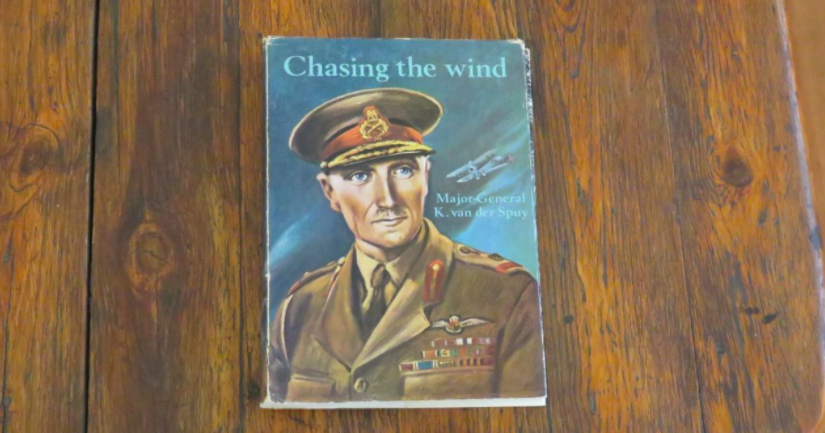

Major General Kenneth van der Spuy’s autobiography ‘Chasing the wind’ (SJ de Klerk)

Early in 1918, while in command of a Training Wing of the RAF, he was invited to form and command an air arm to operate with the British, French and White Russian forces in the Russian north, based at Archangel. In 1919, while out on aerial patrol, his Sopwith Camel aeroplane crashed landed because of engine failure, possibly caused by sabotage, resulting in Van der Spuy being captured by Bolshevik troops and imprisoned until 1920.

After serving in various senior SAAF and UDF capacities, Van der Spuy and his wife Una retired to their historic Cape Dutch gabled homestead ‘Old Nectar’ with its beautiful garden in the Jonkershoek Valley near Stellenbosch. The garden of Old Nectar largely created by Van der Spuy and his wife, remains the only private one in South Africa to have been designated a national monument.

‘Old Nectar’ in the Jonkershoek Valley (via safarinow)

Most components of the Imperial Gift arrived in South Africa early in 1921 and Van Ryneveld and Van der Spuy explored the countryside for kilometres in every direction around Pretoria, before deciding in April 1921 on a site named ‘Zwartkop’ on the Johannesburg-Pretoria main road, about 3 kilometres east from Robert’s Heights, (later renamed Voortrekkerhoogte, now called Thaba Tshwane).

Because the owner, Dale Lace refused to accept the proffered price, the government expropriated the eastern portion of the farm Zwartkop for the aerodrome. The advantage of the Zwartkop site was its proximity to the nearby Artillery Depot, subsequently re-designated as the Aircraft and Artillery Depot.

Almost immediately work commenced on levelling the landing ground and improving the pathways connecting the three sites, which would collectively allow for air force operations, namely; the airfield, the Aeroplane and Artillery Depot and SAAF Headquarters House accommodated in the old British military HQ building.

The first structure to be erected was a wood and canvas Bessoneau hangar of the type commonly used first by the RFC and then the RAF, in Britain and on the Western Front. It was a structure designed to be erected by 20 skilled men in as little as 48 hours. Unfortunately, the Bessoneau hangars no longer exist.

Bessoneau Hangar, location unknown (aviadejavu.ur)

During the following two years, 16 of the steel Imperial Gift hangars were also erected at Swartkop where they may still be seen.

Steel hangars from the Imperial Gift still standing at Swartkop Airforce Base (SJ de Klerk)

The new aerodrome was called Zwartkop Air Station and retained this Dutch spelling until about 1950. Swartkop Airforce Base is now considered to be the oldest operating air force base in the world.

The initial work had barely been completed before the government called upon the SAAF to assist with suppressing the 1922 Rand Revolt. This event initially commenced as a general strike by coal and gold mine workers in January, but by March 1922, as the attitudes of the Chamber of Mines and the striking militants in the trade unions hardened, it developed into a fully-fledged White labour revolution on the Witwatersrand.

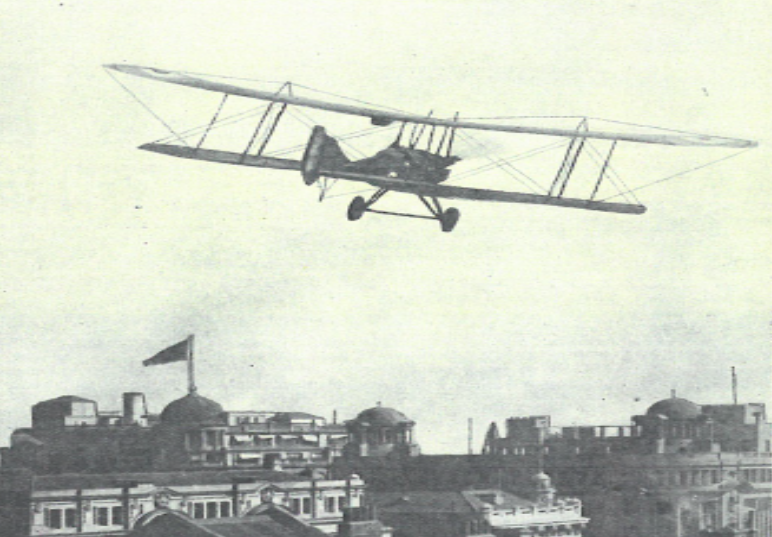

SAAF DH9 flying low over Commissioner Street towards Fordsburg (SA Pictorial)

Hastily armed with Lewis guns and World War 1 bombs, SAAF DH9’s flew 172 missions against the striking mine workers in Fordsburg, Benoni and Brakpan.

Two of these aircraft were forced to crash land due to accurate ground fire by strikers who had served in the military during the recent World War. One crashed on Aasvoëlkop, now better known as Northcliff Hill.

Northcliff Hill (Rod Kruger)

Derisorily called ‘Smuts’ Mosquitoes’ or ‘Jannie’s vultures’ by the defiant strikers, the SAAF bombed and strafed striker positions, dropped leaflets urging them to lay down arms and provided the military with valuable information on striker positions and entrenchments. Amongst others, aerial photographs of striker trenches in Fordsburg were taken.

DH9, from the Imperial Gift, at Ditsong Museum of Military History, Johannesburg (SJ de Klerk)

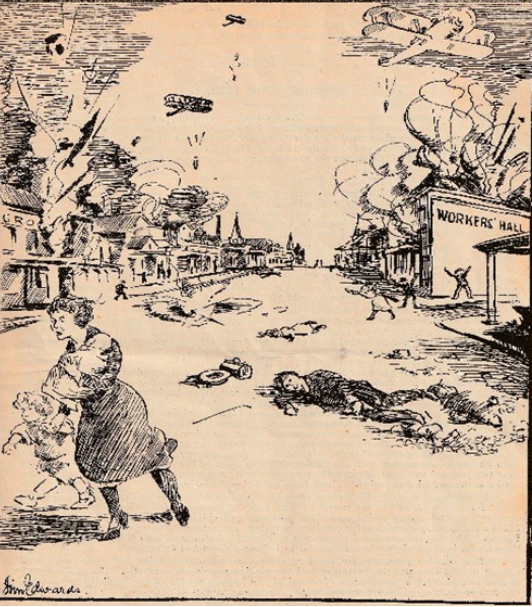

At least one innocent victim, ‘old’ Mrs. Maria Truter was killed when the SAAF by mistake dropped a bomb on the Park Café, corner of Woburn and Bunyan Streets, Benoni. Presumably, it is the incident illustrated below. Note the half-obscured advert indicating ‘Grocer’, on the bombed building on the left.

Striker perspective of the SAAF’s bombing of the Benoni Mine Workers’ Hall, but targeting innocent women and children instead (The Story of a Crime being the Vindication)

The SAAF claimed some of these bombs were shot off their racks by striker fire from the ground, while the strikers maintained it was part of an aerial terror campaign against innocent civilians.

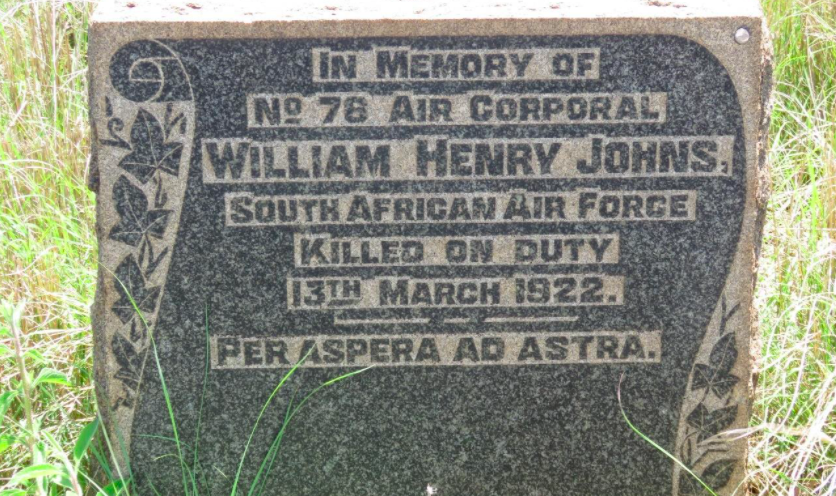

The air force also suffered its very first deaths in action during this Revolt, namely Captain Carey-Thomas killed on 10 March and Air Corporal William Henry Johns on 13 March 1922.

On Friday 10 March 1922 an estimated 500-700 strikers attacked the shaft and adjacent offices of the Brakpan Mine. A small assortment of mine officials and Special Constables attempted to defend the property but surrendered when their ammunition ran out. Subsequently, several of the defenders were shot or bludgeoned to death by the enraged strikers.

When the SAAF later flew over the area, Captain W. W. Carey-Thomas MC, Adjutant of the SAAF, who had been a senior Mine Official on the East Rand prior to World War 1, and serving as aerial observer because of his knowledge of the area, was killed by a bullet through the heart.

Air Corporal Johns, while serving as crew on a Whippet tank at Benoni, was killed by a bullet penetrating the tank’s visor.

Carey-Thomas and Johns are both buried at No. 1 old Military Cemetery at Thaba Tshwane. Their graves are situated adjacent to each other in an overgrown and rather unkempt section, behind the well-maintained Commonwealth war graves precinct.

Tombstone of Captain Carey-Thomas at old No. 1 Military Cemetery Thaba Tshwane (SJ de Klerk)

Tombstone of Air Corporal Johns at old No. 1 Military Cemetery Thaba Tshwane (SJ de Klerk). The SAAF Latin motto means ‘Through adversity to the stars’

This was the first and last occasion armed SAAF aeroplanes flew combat missions against targets in South Africa.

Barely had peace returned to the Witwatersrand when the SAAF was again called upon to support government forces, this time against the rebelling Bondelswart, a Khoikhoi clan, whose reserve was then situated between Klein Karas and Warmbad, in the southern region of South West Africa (SWA), now Namibia.

The Bondelswart insurrection, although minor compared to the Rand Revolt, caused some embarrassment to the Smuts government, as it was roundly criticised by South African and British politicians for transgressing the conditions of the mandate granted in 1920 by the League of Nations to the Union of South Africa to administer SWA.

Both the Ditsong Museum of Military History in Johannesburg and the SAAF Museum at Air Force Base Swartkop are definitely worth visiting by those who may be interested in South Africa’s rich military history.

I wish to thank the Curator at the Ditsong Museum of Military History in Johannesburg who kindly granted permission to photograph the aircraft inside the Adler Hall.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Bibliography

- Brent B. (non-dated). 85 Years of South African Air Force. African Aviation Series No. 13. Freeworld Publications, Nelspruit.

- Beyers C. J. Editor in Chief. (1987). Dictionary of South African Biography. HSRC, Pretoria.

- Freislich R. (1964). The Last Tribal War. A history of the Bondelswart Uprising which took place in South West Africa in 1923. C. Struik, Cape Town.

- Hancock W. K. (1962). Smuts. 1. The Sanguine Years 1870-1919. Cambridge University Press.

- Hancock W. K. (1968). Smuts. 2. The Fields of Force 1919-1950. Cambridge University Press.

- Illsley J. Lieutenant (non-dated 1986?). Swartkop 1921 – 1986. A SAAF Museum Publication.

- Illsley J. W. (2003). In Southern Skies. A Pictorial History of Early Aviation in South Africa 1816-1940. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- L’Ange G. (1991). Urgent Imperial Service. South African Forces in German South West Africa 1914-1915. Ashanti Publishing, Rivonia.

- Lewis G. L. M. (1977). The Bondelswarts Rebellion of 1922. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts of Rhodes University. Grahamstown.

- Nöthling C. J. Colonel & Martins Du P. Major. (1990). History of the South African Air Force. Directorate Public Relations SADF, Pretoria.

- Van der Spuy K. Major General. (1966). Chasing the wind. Books of Africa Pty Ltd., Cape Town.

- Van der Spuy U. (2009). Old Nectar. A garden for all seasons. Jacana, Cape Town.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.