Once Natal became a British colony in 1843 there were opportunities for British immigrants to come as settlers, farmers and craftsmen. Over time thousands of such hopeful people arrived by sailing ship to start new lives, establish families and make their fortunes on farms and plantations and estates in Natal from about 1850 onwards or to populate the principal towns, Durban, Pietermaritzburg and Ladysmith. Prior to railways, travel inland was arduous so these were pioneers who had to be resilient to survive and thrive. The book opens with the story of Harriet Nicholson who sailed from London in April 1850 on the Sandwich, a small sailing ship which was part of the convoy of twenty ships chartered by J C Byrne to bring settlers to Natal. She kept a journal of the three month voyage to Durban - she killed off bedbugs and revelled in the sea life encountered on a long voyage. The Nicholsons came to settle In Richmond and transitioned from tents to huts to a farmhouse; and some 165 years later and six generations down the line, the Nicholson family still farm in the area.

Jacqueline Kalley has gathered the stories of these British settler families, and links the families to the estates and farms established in the colony of Natal. The objective is to tell the history of the farms and the original families as well as to include the families who later fell in love with perhaps a lonely neglected old farmhouse and wanted to restore such a property. I love the rhythm of lives unfolding through successive generations. Jacqueline is a trained librarian (she has a PhD in Information Studies) and a publisher. The book enables her to show off her dual enthusiasm for family histories and heritage buildings. She describes herself as a contributor and editor but Jacqueline is clearly the author. She wrote nearly all the stories though there was input and cooperation from more than fifty participants. She told me that there were only two family farm stories where the owners wrote most of the text, but even there she edited and embellished those chapters.

Book Cover

She decided to write the book following her return to Natal after a working life of thirty years in Johannesburg. It is so often the case that a return to childhood haunts brings a fresh eye and an excitement as one realizes why those half familiar fields, smells of home and houses of one’s youth are special. Jacqueline is keen to engage with people’s roots and ancestry. Why is there a sensitivity to the land, its cultivation and the preservation of heritage among these landowners, still living on farms owned by their families for generations? This is not to ignore the complexity of ownership and historic patterns of settlement based on conquest and occupation, new settlements, new cultivation. Natal became a British colony in 1843 and in the context of the popularity of organized emigration as a solution to English social problems, some 5000 settlers came to Natal through the Byrne scheme between 1849 and 1853. The farms of the Midlands were surveyed and and the rights of any prior indigenous customary occupants gave way to precise measurement and title deed registration. The reality faced by the immigrants did not live up to the promises; often land was not suitable for farming and many faced hardships in trying to make a new life. The idea of founding English villages a long way from Maritzburg or Durban was not practicable. There were many false starts.

One story wrapped up in a double page illustration (pages x and xi) of what appears to be a plan or a map of a farm, reveals a layered and rich history. Unfortunately the author has not explained the significance of this clearly very old document. Unfortunately there is no description to this illustration, so superficially it is just a decorative insert for scene setting. However, I discovered that this antique document is the title deed of the farm Heavitree in the Mooi River / Estcourt district, owned and farmed by the Ralfe family for 170 years. There are a number of dates on this title deed, some official stamps and signatures of authority. Close study of such a document shows why a title deed with official legal status with the imprint of the newly established colonial government was such an important device to claim a farm. Ultimately individual ownership of a farm made it possible for a bank to lend and land to be used as collateral. The coming of the British colony of Natal gave the Crown (or in other words, the British government the legal right to declare all land as Crown land and hence to establish a mechanism to alienate or sell the land to new settlers. Once a farm had been established, surveyed and registered, it could be sold by the British crown and was on its way to the concept of private property. If a person could prove ownership and his title established backed by the courts and a legal system, then the estate could be used for surety and mortgaged to raise larger capital sums to invest in improvements or build a substantial homestead. Originally the farm Heavitree was called Eden and Gary Ralfe, the current owner and descendent of the first member of this well-known Natal family (a Robert Ralfe) believes that this biblical name signalled that the farm had been surveyed during the short-lived Republic of Natalia before the British proclaimed the Colony of Natal in 1843. But the coming of British rule meant that the Voortrekkers having fought the Battle of Blood River for supremacy over the Zulus, then trekked back over the Drakensberg to make their homes and claim political independence across the Vaal and in the Orange Free State. What the Afrikaner community had started was now left to the British to consolidate and develop if they could attract British immigrants.

The Ralfe family came to Natal in 1850 as Byrne settlers and when they settled on Eden they were forced to pay the British colonial authorities two shillings and sixpence an acre. A bequest from an elderly aunt who lived in the village of Heavitree near Exeter, Devon, enabled the Ralfe family to both pay off the Crown commissioners and buy up neighbouring farms. The first local Ralfes hence both honoured the generous aunt and established their right of ownership. The way was clear to sell portions of their farms and to raise mortgages. Gary Ralfe explains that, the various annotations on the deeds are about parts of the farm that were sold off, two servitudes in favour of Natal Colonial Railways, and various mortgages taken out by his spendthrift great grandfather, another Robert Ralfe. There is a series of official stamps, signatures and dates so that a title deed becomes a timeline of land transactions. This is the sort of original document that pops up in this book and if you are curious, progresses the reader through several generations of these intrepid Natal families and their histories as well as their farmhouses. It is an omission, in this particular instance the author did not connect the title deed and the history of the Ralfe family of Heavitree to a title deed that is about Eden. I found this to be one of the most intriguing of family sagas, but one can also read into this one family’s saga, another story of prior dispossession of earlier tribal people who did not function in terms of title deeds, land sales, crown oversight and mortgages. There is a fundamental question raised relevant to current land claims and reparations - the road to economic development has to be through individual landownership. Without legal papers land is not a long term asset.

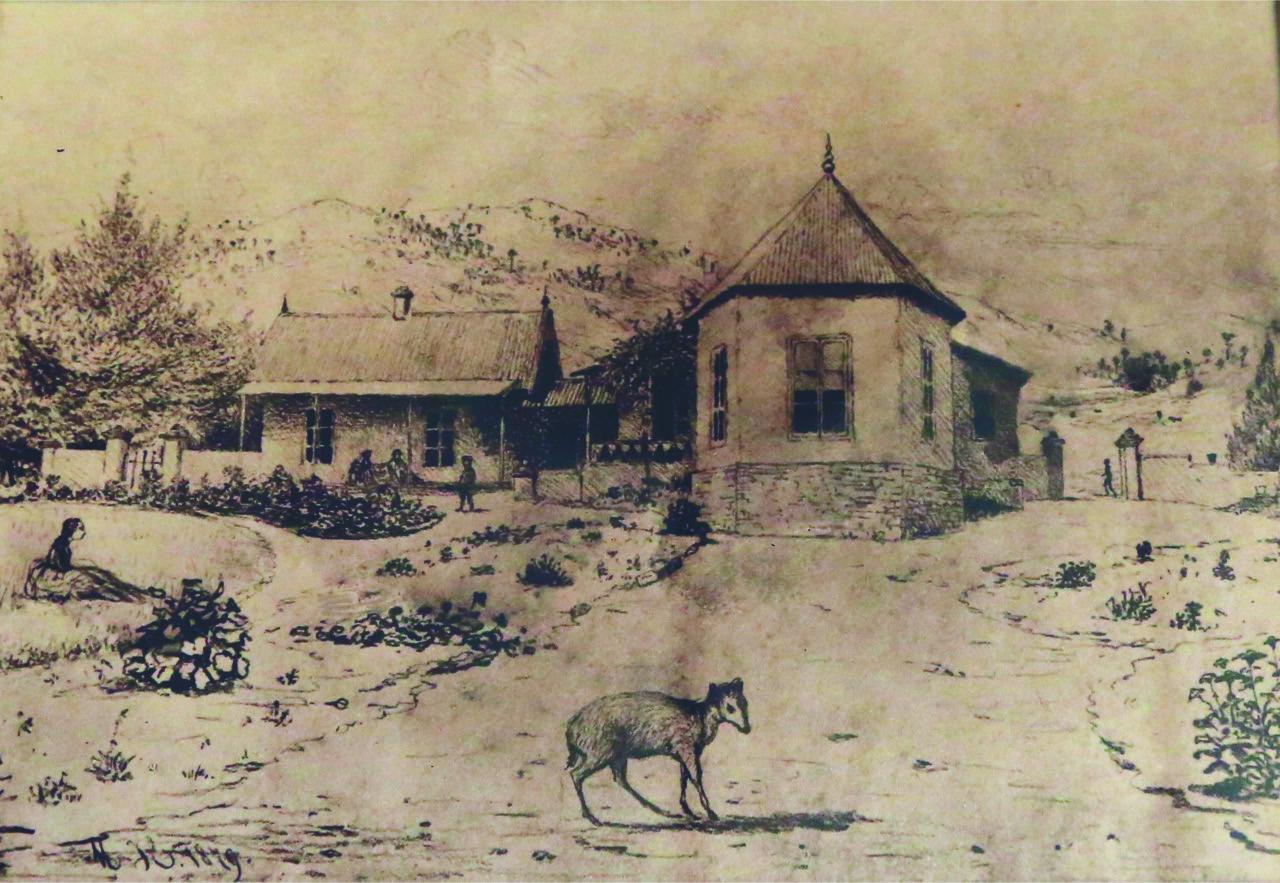

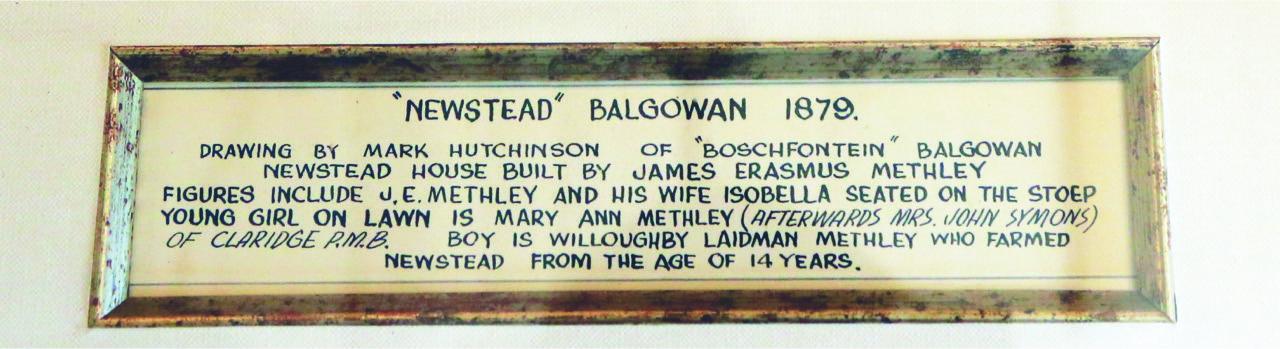

Newstead in the Balgowan district, built in 1870. It belonged to the Methley family.

Where are the farmhouses of Old Natal? They are to be found scattered throughout the Midlands of KwaZulu Natal, across ten localities of European colonization and settlement of the 19th century. Their presence tells the story of a lifestyle that becomes ever more difficult to sustain in the 21st century. This is an important book because it is both about the history of these farmsteads and gives a glimpse of current life - a now moment captured for posterity. It’s a lifestyle that may not last another century. Geographically this selection of farms falls within a circle easily reached by car from Pietermaritzburg. The names are familiar - Hilton, Karkloof Valley / Howick, Mooi River, Escourt, Greytown, Balgowan, Boston Road, Richmond, Dargle Valley and the Southern Drakensberg.

Between two and eight farmhouses in each area are covered in some detail. Some 40 farmhouses were visited and described. A short essay introduces each area followed by a two to four page essay on each estate, its family and its farmhouse. Most of these farmhouses were built in the second half of the 19th century and constructed from a mix of local timbers (such as yellowwood), local red brick, quarried stone, and sandstone. Roofs were often thatched or made of imported corrugated iron. Window frames were imported. These homesteads were spacious, gracious and rambling with many rooms for large families. Guests were always welcome. The farmhouse was meant to be at the heart of a working farm enterprise - so there would be an office, storerooms servicing the business side to the property. Around the principal farmstead would be stables and barns, stock rooms and probably a farm dairy. Farms and estates of this size were often self-sufficient; the men living on farms played polo or made up their own cricket teams. Drawing rooms were designed for grand pianos and the right acoustics for home concerts given by the ladies.

The book has great visual appeal with photographs from old family albums and colour photographs of these houses today. Full and even double page photographic spreads are feasts for the eye with a mix of external and internal views. Unfortunately the photographs, splendid as almost all are, mainly lack labels, descriptions and precise dates. The reader has to guess the time period from the look of an old photo or the clues given by clothes worn by the people.

The book is not a guidebook in any sense, although it is a rich compendium of a lifestyle and that specific Natal English culture. There is no hint of a Cape Dutch tradition of architecture in Natal, the style is 19th century, heavily Victorian in feel, imported English counties farm architecture with the touch of the fanciful or grand thrown in occasionally. The homesteads were built and owned by solid people of ambition with dynastic dreams. It is the stories of the people who lived their lives through the decades that bring the houses to life. Gradually the English people who came to Natal found their way towards permanent settlement. Each house has its story and we hear the voices of the original hardy settlers and their descendants. The result is a social fabric woven across memoirs and photographs; the eye is drawn to detail and the meaning behind a treasure or the texture of a wall. The author successfully captures a lifestyle and a culture of a particular type – unashamedly very English and very colonial of old Natal. That old joke about Natal being the last outpost of the British Empire has authenticity in this context.

The frontis page shows a close up view of a beautiful textured wall with the date 1887 etched on a brick - but where is this place? But perhaps these a quibbles that can be set aside.

This is not an architectural history though the author draws on the work of architectural historians such as those by Brian Kearney (Architecture in Natal 1824-1893, published by Balkema, 1973) and Denise N. Dorning (Chimneys in the Clouds – an overview of many of the historic buildings in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands 1845-1925, published by Brevitas, Howick 1997). Those books are long out of print and did not contain colour photos, so a new book on the farmhouse of the Midlands of Natal is welcomed. This is a more ambitious book as it benefits from the advances in publishing and the reach of the colour photographs.

Jacqueline’s passion for heritage buildings is palpable. Her love of old houses is infectious. She grew up in Pietermaritzburg and tells me that the house she grew up in was quite old with many original features. The old architecture of Pietermaritzburg inspired the author. She was always fascinated by the buildings and tells me that when the YMCA was demolished she was devastated and she was only about 14!

Her mother was an Anderson and grew up in the Donnybrook area. She grew up with the stories of the Andersons who lived there - it was Anderson country! She has written a chapter on the Anderson farms in the Southern Drakensberg. She wanted to celebrate this pioneering family who are still in the area five generations after John and Mary Anderson arrived at Port Natal in 1850. Their ship, the Minerva, was wrecked on the rocks as it lay moored just off the Bluff but John’s toolbox was ashore and he was able to make a living as a millwright and wagon builder. Farming was an initial disappointment but these early settlers were resourceful and skilled in trades such as blacksmithing and carpentry.

Jacqueline’s familiarity and love of the Natal country comes through. She shares with me that she used to spend weekends at Selsley, a farm in the Dargle Valley. The beauty of the landscape made a lasting impression. She adds that it was so beautiful and made a huge impression on me. That Valley is one of her favourite places in the Midlands. The serenity amidst the busyness of the working farms. These farms do need to pay their way. This book captures both the feel and the social and economic lifestyle of these farms and their families.

Her own favourite farmstead is Tweedie Hall in the Dargle Valley near the Midmar Dam. This house was built by James and Eliza Morton from Scotland and the name comes from Tweedie Hall in Scotland where they were married. They arrived at Port Natal in 1868. They purchased their farm and over time acquired some 12 000 acres of land. James Morton sold agricultural machinery and he built the first silos in Natal. Their home, was designed ty the Natal architect William Street-Wilson, a double storey manor house with corrugated iron roof and fronted by dual volume upstairs and down stairs verandas. The family story is an interesting one of the legal processes of inheritance but also usufructs. David Marshall, the current owner, is the great grandson of Eliza and James so the home remains in the hands of the original family, and generations of Mortons are buried in the family graveyard overlooking the Midmar Dam.

Tweedie Hall

Jacqueline’s plea is for an appreciation and a celebration of these old family homes. Many of the old farmhouses of old Natal are in a parlous state. There have been demolitions; some have been lost to fire and others have been abandoned.

The subtext to the story of the farmhouses and their families was the agricultural economy. These farmhouses were at the centre of working farms and productive estates. The diversity of productive enterprise impresses – the Midlands of Natal is fertile with good rainfall - cattle, dairy farming, pigs, sheep, timber, fruit, vegetables and horses lay behind farming success and the accumulation of family capital through the generations. There were disastrous years of drought or rinderpest but hard work, persistence flourish.

The success of this book is its championing of both built heritage and family histories. Many of the stories are sad. Some lives were long and well lived, others cut short by illness and accident. The time period is roughly the 1850s to the second decade of the 21st century. Every farm tells a story of arrival, surveying of land and creating of farms, a pioneering phase of hardship and then gradual improvements, a farmhouse first built and then expanded and an enduring home emerging where families were raised and returns on investment reaped. I liked the story of Fair Fell, a farm situated between Howick and Karkloof. It was the home of the Sutton family who came to Natal from Lincolnshire after first immigrating to Chicago. Industrious and hardworking George Sutton made his own bricks in order to build his farmhouse in the 1870s. Sutton lost his wife, Harriet only four years after they moved into the farmhouse. She died of consumption or as we call it today tuberculosis. He continued farming but also entered politics and became the Prime Minister of Natal for two years in the 1890s. He advocated responsible government, a step on the road to local self-government for the Natal colony. Sutton remarried – his second wife being a widow Mary Pascoe. Fair Fell was declared a National Monument in 1994 and the farmhouse, today a restaurant Yellowwood, proudly bears a National Monuments’ bronze plaque. The farm remained in the Sutton family hands until 1980 but there have been three owners since.

Another story I enjoyed was that of the Shaws of Shawswood near Howick (Karkloof). The farmstead dates from 1880 and remarkably the farm has always been and remains in possession of the Shaw family. They are the descendants of the first Shaw who landed in Natal in 1850, but who initially faced tough times and false starts. The Shaws were polo players; they bred and trained their own ponies and established a polo team.

Often these farms in passing through the generations accumulate antiques and past treasures to the point of amassing a museum - old account books, photographs, old diaries, farm implements, and lace wedding veils. Often a farm and its possessions, treasures, old farm implements and tools as well as the family graveyard is a time capsule and an extraordinary It historic record.

This book recounts the remarkable journey of the author/editor with photographer, Hugh Bland, to find these families and their farmsteads, rediscover her own youth and document and learn about and retell the family sagas. Choosing the featured properties could not have been easy. This book must be a choice item for a library of Nataliana, the result is a rich feast that will delight collectors, Natal history fans and family history enthusiasts and the heritage community. It is a volume that belongs on the coffee table of each and every one of these homes. But it is also a book that belongs in a library of Africana. The advantage of combining the tasks of publisher, editor and writer means that the volume has a quality feel; large format and easy to read text as well as a superb selection of photographs. A collector’s edition and a standard edition have been published with the collector’s edition for the subscribers and sponsors. There is a subscription list. A bibliography and a name index shows careful attention to the scholarship.

I found the book on sale at Exclusive Books. It immediately appealed and I made contact with Jacqueline Kalley. A new edition was in press. It is now available and a copy can be purchased from the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation for R600. Email mail@joburgheritage.co.za.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.