This book is a wonderful introduction to a unique South African architectural tradition - the corbelled structures of the Great Karoo. The book immediately engaged my interest and had this not been a stay-at-home time of pandemic, I would have been packing a bag and heading for the Cape, book in hand. It is so dense with information and photographs that it immediately becomes a big guide book to a unique part of the world - the Karoo. It is a cross between a travel guide and an introduction to archaeology and architecture. It is very much a “how to do book“ about documenting the built survivors in a remote landscape. It is practical, makes the subject accessible and is deceptively easy to understand.

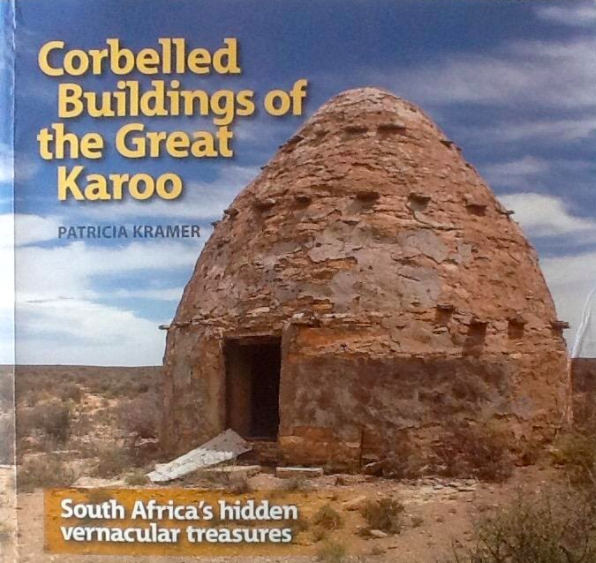

Book Cover

The design of the book is a delight - several clear colour photographs on every page; a handy size that would travel well in a car’s glove box and a readable text with brief explanations on each page. The book was in my hands for no more than half an hour and I made up my mind to contact Pat Kramer and begin to plan a post-Covid time journey to the Karoo. Normally, when driving the long road from Gauteng to the Western Cape, the Karoo is that endless straight road ahead, through seemingly boring country with clear blue skies, sparsely populated. Towns are distant from one another and this is where one is most tempted to break all speed records and push through to the Cape passes. Well, the message is stop racing, take time to linger and learn about these hidden vernacular treasures, with this book in hand.

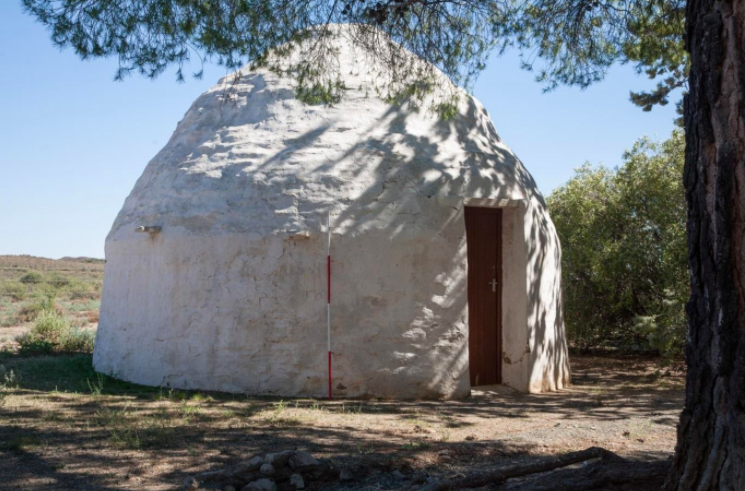

Photograph of a corbelled structure (John Kramer)

Corbelled buildings are unusual rounded beehive-like structures. They are a fascinating building form. They are to be found in the Karoo within a kite shaped expanse of country that stretches between Williston, Carnarvon, Loxton and Fraserburg. Hitting all four towns means covering about 400kms. To explore, you need to turn off the main N1 at Victoria West or Beaufort West travelling in a westerly direction. It is a treeless expanse, an almost desert landscape, with less than 200mm of rain per annum.

Here is the first clue why corbelled structures are found in this part of the world. The lack of trees means that timber was scarce. It was expensive to transport wood from the forest areas to use in construction. For poor people, an alternative material for building had to be found. Stone is a local cheap material, readily available for the price of manual labour. Layered, fine grained stone could be split with a pickaxe or a crowbar into building blocks and used to construct shelters for people and animals or to make an open air oven in the veld.

The corbelled building is made of relatively small stones using the technique of corbelling to shape a domed structure. Layers of hand size stones could be laid one on the other in a circular shape. Each tier of stone rests on the one below; the art of construction lay in the precise balancing of stones. Start with using a trained eye to select stones of the right weight placing one layer of stone upon the next, with each layer achieving a slight pitch inwards. As the tiers rise, the building forms a dome; it looks like a beehive. Ultimately at the top of the dome there is a hole at the centre and this is closed with a large stone called a roofstone. An outer layer of stone acts as a counterweight. The result is a beautiful rounded domed building, white washed on the outside and stone textured within.

Interior of a corbelled building (John Kramer)

Corbelled buildings have a long tradition and such domed structures are to be found in other parts of the world. The technique was known and used in diverse societies in poor often remote parts of the world. The author provides some illustrations of examples from Hirta, an island off Oban in Northern Scotland. The technique was known in ancient Egypt as well as on Mediterranean islands. I have seen the corbelled technique in use high in the mountains not far from Shiraz. It’s a building form that fits into the term “vernacular” and the question bubbles up, how did this ancient form known in other parts of the world come to South Africa and the Karoo?

Corbelled buildings belong to vernacular architecture. This is where archaeology and architecture connect. Vernacular architecture is all about buildings constructed by local people for their own use, using the materials that were readily available in their local surroundings. You did not need an architect to design such a building – you needed a patient stone mason or a craftsman with long stretches of time on his hands.

There is an active Vernacular Architecture Society of Southern Africa based in the Cape, with an impressive website (click here to view). The study of vernacular architecture was the speciality of James Walton (1911-1999). It reaches into the disciplines of archaeology, architecture, and anthropology, with a touch of the antiquarian. Walton was the founder of the society. He built his reputation on documenting vernacular. Wherever he went he recorded and in the process produced many books and articles. Walton’s books in the broad field of vernacular architecture are highly collectable today. Walton wrote on diverse themes such as homesteads, and villages, dovecots and cottages. He published an interesting article on Corbelled buildings in the South African Panorama in 1961 and this has been reproduced on the Heritage Portal (click here to view). Pat Kramer follows in the footsteps of Walton and is his intellectual successor. The society backed the study of the corbelled buildings of the Great Karoo with an ongoing project to record and document with systematic commitment.

The book sets the scene with background history on the 18th century moving Cape frontier and the life of the trekboer. Pastoral farming meant movement across open spaces regardless of race or origins.

Kramer postulates that it is possible that the trekboer knew about corbelling. It could have been part of the imported cultural capital but trekboers were pastoralists and on the move so did they build to settle in one place? Another possibility were indigenous roots. A Sotho-speaking people, the Mantatees, had a tradition of building small corbelled huts of stone in the Free State and north of the Vaal in the Marico district. Hence there are a number of theories about origins with evidence of drawings and sketches of early travellers such as Thomas Baines and Andrew Anderson. One interesting variant was the outdoors bakoond or stoneoven in corbel shape. Lime kilns too were built with this method. Did this building form evolve in Southern Africa independently or was it a learnt technique? It is hard to take a firm position. A tentative conclusion is that trekboers possibly knew about corbelled roofs or building lime kilns or bakovens but in the 18th century indigenous corbelled huts were also constructed.

Pat Kramer reaches the conclusion that origins lay in mixed influences, but that the great period for construction in the Karoo was in the 19th century, rather later than the 18th century frontier, over a 70 year period from the early 1800s to approximately the 1870s. These were enduring structures and some of the corbelled buildings were inhabited by farmers in the region until the 1950s. Pat has provided an enormous amount of information about the history of specific farms, the materials used, the building techniques and the lifestyles of the micro region.

Most of these corbelled structures had doors but no windows - and with a single rondaval shaped room they were hardly comfortable dwellings. Cooking had to be done outside the dwelling through there are examples of corbelled kitchens. There are even soap making structures in corbelled shape. Tracking, tracing and recording nearly 200 buildings has been the work of Pat Kramer and the Vernacular Architecture Society for over two decades. It has been a labour of love and a passion for Pat and her colleagues. Pat explains “At the age of 60, I was totally seduced by the sight of my first corbelled building, left my job in publishing and returned to archaeology”. It led Pat to then achieve a Master’s degree in Archaeology at UCT with a thesis titled: “The history, form and context of the 19th century corbelled buildings of the Great Karoo” (click here to read).

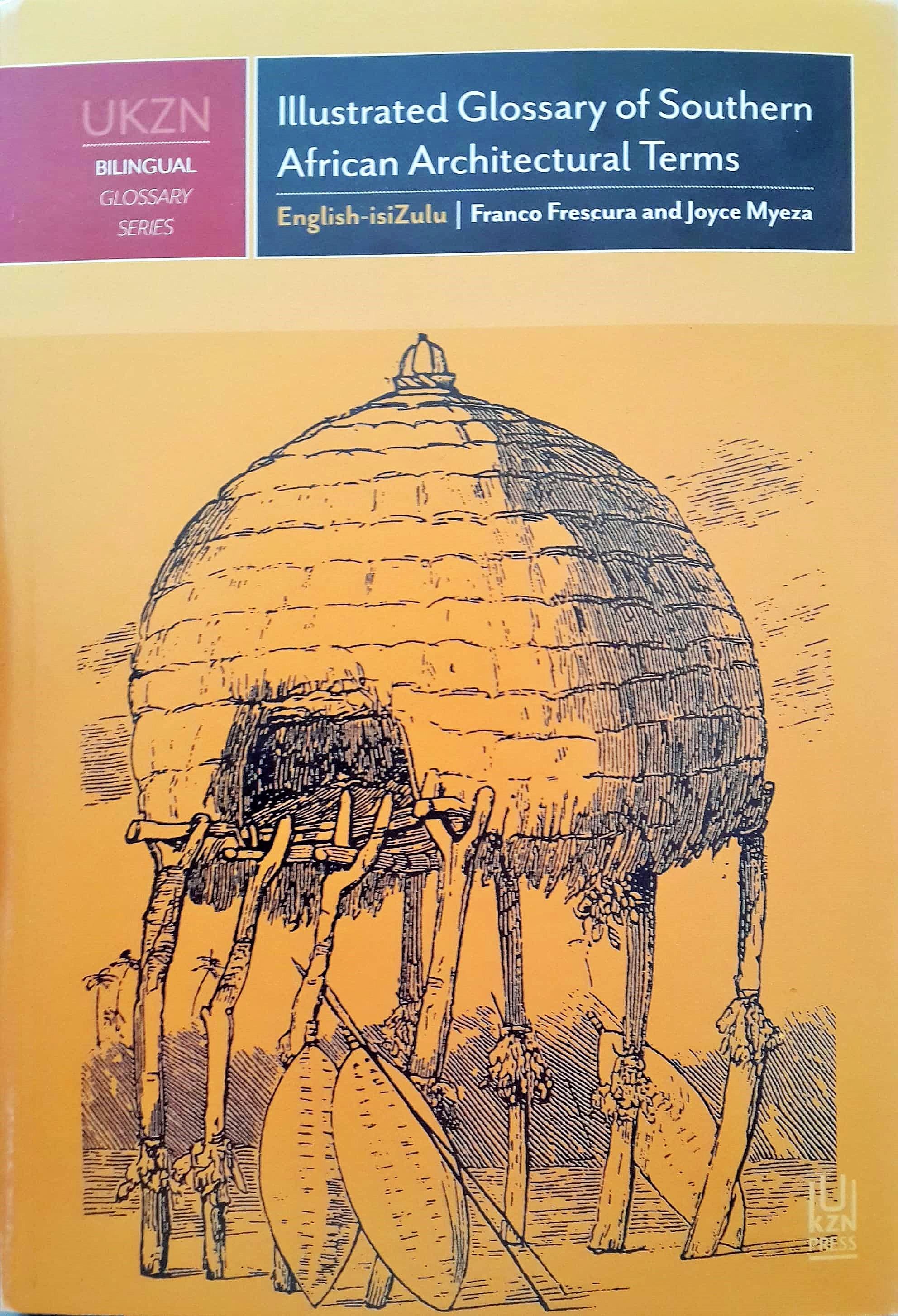

Franco Frescura included corbelled buildings in his “Illustrated Glossary of Southern African Architectural Terms, English-isiZulu: An Illustrated Survey of Historical Terms Appertaining to the Indigenous, Folk and Colonial Architectures of Southern Africa“:

Corbelled Stone Structures: 1. Stone shelters built on the southern highveld and parts of Lesotho, probably before the era of Mfacane when their construction appears to have come to an end. Their relatively small size indicates that they probably were built to house herd-boys or their activities. 2. Sizeable stone farm structures found mainly in the northern Cape, in an area approximately bounded by the towns of Williston, Carnarvon, Loxton and Fraserburg. They were probably built between 1825 and 1875 to house the needs of the local sheep farming community. They are generally circular although, in a few examples, a square or rectangular plan has been used. (Walton, 1989: 122-134)

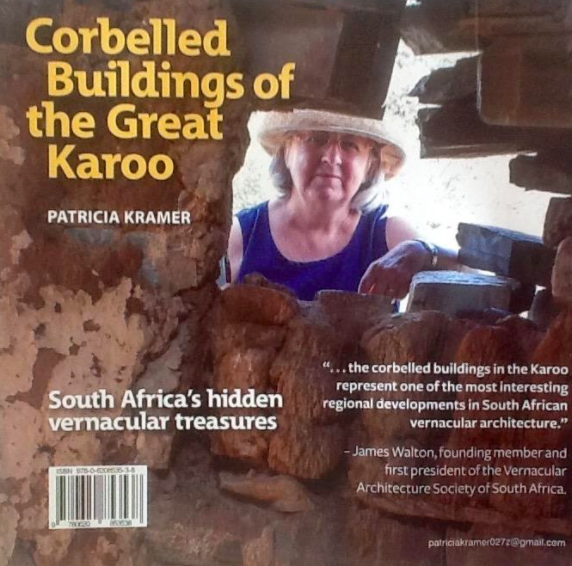

Book Cover

The strong message of Kramer's book is that corbelled buildings should be recognized, documented, mapped, cherished and preserved for future generations. Pat clearly loves the Karoo and in publishing this very accessible book is doing her bit to put the Karoo on the tourist map. But she cautions: “The problem with the corbelled buildings is that they are all on private property and not easily accessible. So you can’t spend a holiday visiting one after another“. Of course with this book in hand, exploring the Karoo with a purpose, rather than wanting to just drive through as one normally does on that long Johannesburg to Cape Town journey, I can see an adventure taking shape, even if there is not a line-up of 200 buildings to be seen on an easy drive. It dawns on me that that this journey in search of these structures might just be a little bit of a challenge; planning has to precede adventure.

Karoo landscape with a Corbelled building (John Kramer)

Arbeidersfontein is the most accessible as it is a short distance off the Williston-Carnarvon Road (R63). It was declared a National Monument in 1980 but with the changes in monument management slipped into protected provincial heritage status. Pat explains: “It can be visited by asking the farmer for the key”.

Pat offers another tip: “The other easy way is to actually stay in an historic corbelled building“. Osfontein and Stuurmansfontein are both available to accommodate visitors. Osfontein is near the main farmhouse, while Stuurmansfontein is what Pat calls “fabulously isolated” (see pages 114 and 115). Another suggestion is to try Vaalhoek as it is now available for very basic accommodation. Pat explains: “Two other options are the corbelled buildings moved from a farm and rebuilt... one in Carnarvon (very good) and one in Fraserburg (locked).”

Quality photographs are the essence of the successful contemporary recording of old buildings. The photographs were mainly taken by John, Pat’s husband. Pat regrets that she and John have captured relatively few of the many corbelled buildings which the Vernacular Architecture Society team has documented. But I congratulate the author and her photographer husband on their work. They have handed the reader and traveller a treat.

Back cover of the book

Availability at time of writing: The price is R340 plus postage and it is available from Pat Kramer directly: studio@iafrica.com. It is also available from Clarke’s bookshop in Cape Town and Verbatim Books in Stellenbosch. Only 200 copies were printed for the first edition and these have almost sold out.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.