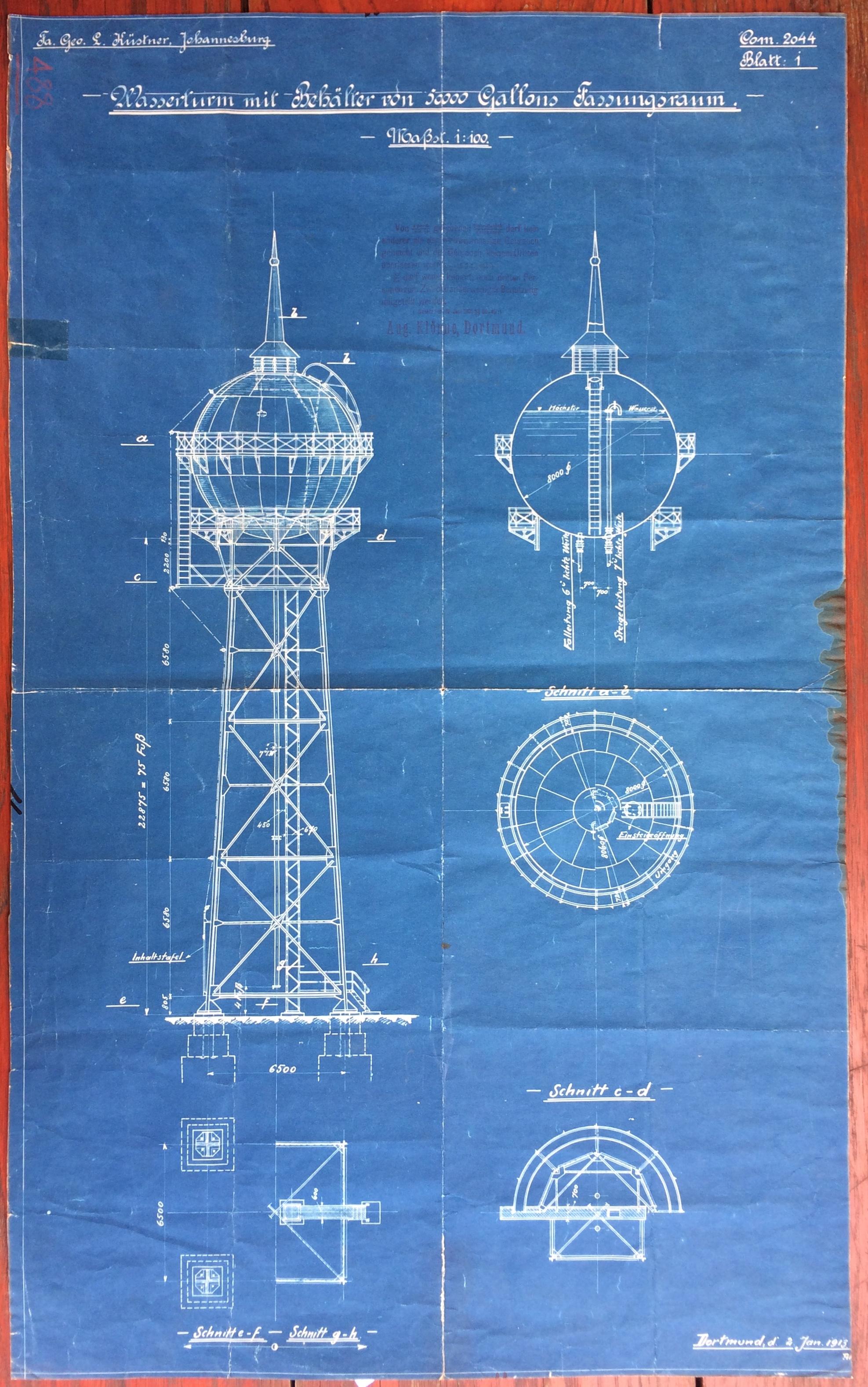

I read Politics and Community- Based Research: Perspectives from the Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg with great interest as I have known Yeoville since I was a child and have many memories of the suburb. I have never lived in Yeoville but I have visited friends, was a regular cinema goer at the Piccadilly, shopped in Yeoville, bought petrol at the garage on Cavendish Road, used the tailor and bought fabrics down Rockey Street and swum in the Yeoville municipal pool. The most reasonable locksmith and cobbler are still at the Yeoville market. Many Johannesburgers of my generation, who were young and hopeful in the sixties and seventies started their independent lives in their own flats in the apartment blocks of Yeoville. It was a place of alternative music, alternative shops, a mix of restaurants, and nightclubs with bright lights partied through the night. Muscle men with tattoos on beefy arms and leathers roared down Raleigh. Yeoville always had a spunky air of defiance and an easy mix of colours and cultures. Novels have been written about life in Yeoville; the suburb features in memoirs (even Trevor Noah mentions Yeoville visits to his father), Anna Smith included the Yeoville Water Tower in the decorations for her book on Johannesburg Street Names and the sketch leads into the letter “Y”; memories of life in Yeoville are vividly captured on the pages of the Facebook group “We Grew Up in and Around Yeoville'' and it has over 6000 members. I was excited when I found the original blueprint of the Yeoville Water Tower dated 1913 and that turned into a research project. Enough before I get absorbed by my Yeoville memories.

Blueprint of the Yeoville Water Tower (Kathy Munro)

Yeoville Water Tower (The Heritage Portal)

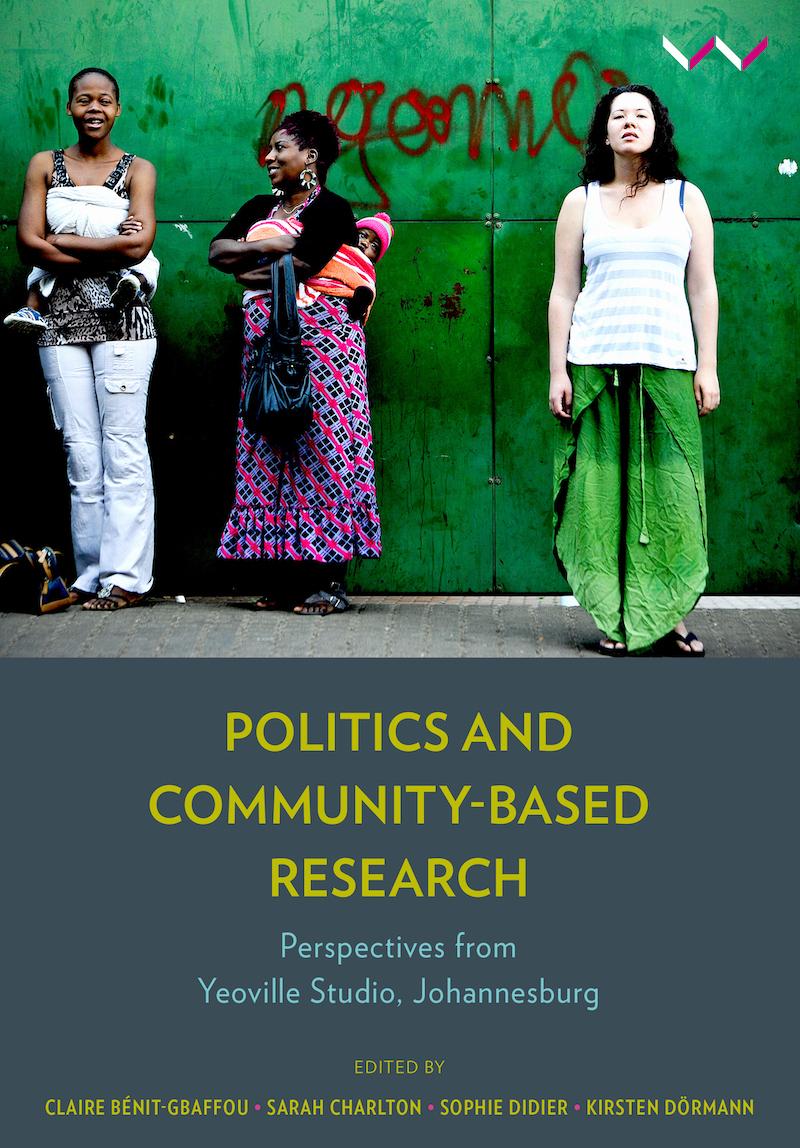

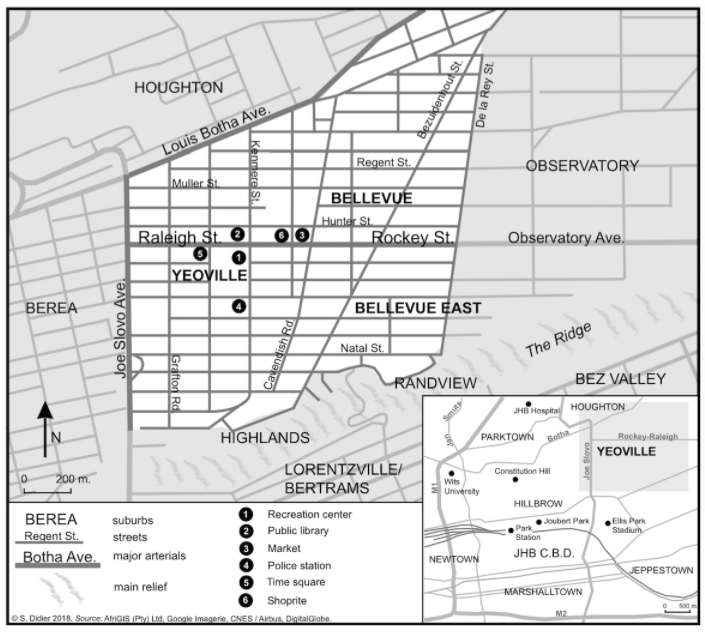

My first observation is that I thought that this book is about Yeoville - and it has an intriguing picture of three women of Yeoville; there is an introductory chapter on Greater Yeoville and a map locating the suburbs of Yeoville, Berea and Bellevue. If you are looking for a book on Yeoville history you will be disappointed as this book is a serious academic study of Community based research and teaching methods. It is by and for earnest researchers, teachers by teachers and their post graduate students. Yeoville is their site of study.

Book Cover

Map of Yeoville (Yeoville Studio)

In writing this review I found myself almost too close to the place, namely Yeoville and I rushed in to write up the history of Yeoville and the story of Thomas Yeo Sherwell who named and laid out the suburb in 1890. My interest is in discovering why Yeoville, which is described as “a dense urban fabric” with a building stock of two to four storey apartment buildings, maisonettes mixed with detached earlier houses with tin roofs and stoeps built on fairly tiny plots, happened to have been created. Yeoville has some excellent examples of domestic architecture from the 20th century. I also found myself writing about my memories of Yeoville. But I stepped back and reminded myself that a reviewer must engage with the book that has been written. The first point to be made is that a history of Yeoville remains to be written and there is another book or two or three about memories of Yeoville. This book will in time become itself an important archive source for other writers; in fact I think it is already a slice of the Yeoville story.

The Yeoville Studio was organized by the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Architecture and Planning and its research arm, the Center for Urbanism and the Built Environment and supported by civil society organisations, such as the French Institute of South Africa-Research (IFAS-Recherche). Funding came from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the French National Centre for Scientific Research. The lead researcher, teacher, writer and editor is the respected French scholar Dr Claire Benit Gbaffou. Although there were four editors, hers is the strongest voice (she wrote or was the co-writer of nearly half the book). Claire was a visiting researcher at the University of the Witwatersrand for several years, but her home base was the Aix-Marseille University. She was the Director of the Yeoville Studio from 2010-2012. The other editors are local dedicated academics Sarah Charlton and Kirsten Dormann and Sophie Didier who is also a French academic and researcher. They led a team of colleagues and postgraduate students who contributed to this book. Many chapters are co-authored. The lead writers are most capable.

The Yeoville Study (Claire Benit Gbaffou)

This book is a record and an account of a two-year community-oriented research and teaching initiative, located in Yeoville. The objective is to capture community voices and at the same time to document scholarly reflections on community politics and a method of teaching. There is a nice dedication to local activists - Maurice Smithers who has written his own book on Yeoville and once had the reputation of being “Mr Yeoville“, George Lebone and Edmund Elias (all important in making the essential local connections).

The idea was to train students to engage with communities in understanding the city. Yeoville became an open air laboratory to teach, to learn and to help the people of the suburb address problems encountered with officialdom in government and property owners, the landlords. The suburb is the place of field work, knowledge production and innovative research but with the intention to change political structures. This study is about a moment in time in the Yeoville story. The time was 2010 to 2012.

The opening sentence by Claire Benit Gbaffou catches with a raw immediacy the problems that face the new Yeoville resident – “evictions, informal livelihoods, illegality, fear, public management and lack of collective control over the neighbourhood are the defining features of daily life“.

Here is a vivid and lively picture about life in Yeoville in the 2nd decade of the 21st century and a case study in urban dynamics. The objective is to document the work of the Yeoville Studio. The researchers believed that relevant findings would emerge from this form of hands-on teaching and that the outcome would be of immediate benefit to local communities and stakeholders. In theory it is a brilliant vision that students who study a part of the city will be trained in how to change the city of the future. University students need to be inspired by their teachers. There is huge satisfaction in going out to do field work and to apply theory to real life situations and to then develop community action programmes that have an intention to effect upgrades and improvements.

This is their story of what they encountered when young people engage with the problems of a community often caught in impossible fraught conditions where resources to meet the needs of poor people are either unevenly allocated or simply lacking. Academic life is always enriched when foreigners contribute their knowledge and ideas and there is something of a utopian striving for a better society with the realization that to transform one needs to engage with politics. Activists of this type are idealists. The ultimate objective was to make a difference. An enormous amount of goodwill shines through.

The many contributors write about the experiences and their encounters with the people of Yeoville. The range of topics covers many aspects of the human condition - being young, love stories, capturing public history, shaping a community, running a spaza shop, sharing a flat, street photography, public art, running an African festival and street trading. There are some reflections on the interface between the formal and informal local economy. The chapter on sharing a flat by Simon Sizwe Maysom is a nice piece of journalistic writing. What happens when xenophobia rears its head and more than half of the inhabitants in what is becoming a very crowded suburb are foreign and likely to come from other parts of Africa. There is not too much history but one chapter looks backwards and explores the music scene of the 1980s and the bubbling up in Yeoville of an Afrikaner counter culture that challenged the stereotyping of all Afrikaners being pro-apartheid. Collectively the chapters add up to a rich sociological time capsule. The book is a resource and a handbook for practitioners and teachers who may wish to attempt similar projects elsewhere in the world. We the readers are enriched by these shafts of light thrown on the lives of people. These are precious vignettes. In many ways this study is a modern Mayhew in Johannesburg. The authors want to make the invisible visible.

There is also an agenda about political activism and a critical reflection on the potential for change. There are underlying sub themes about politics, social activism and subtly or perhaps rather more obviously promoting community politics. But to do this takes decades and it is naive to think that two years gives sufficient time to intervene, build trust and head off in a different political direction. I wondered why choose Yeoville as the laboratory - I suppose it could have been any other part of Johannesburg and local areas all have their own subcultures. Did Yeoville need the studio or did the Studio need Yeoville? I don’t think there is a complete answer. The topography of Yeoville is important in the city of Johannesburg and hence we need to look at how Yeoville relates to say Doornfontein or to Hillbrow; what made Yeoville different from Doornfontein and why did it not become a Hillbrow.

The title Politics and Community-Based Research signals the objectives of the teachers and researchers but is too chunky and heavy a title to signal that this is about a study of an interesting suburb with a fascinating past but an uncertain future. Being on the spot and telling about daily encounters has its limitations - there is too little economic analysis, nothing about schools and education, too little thought given to policy formulation to guide deep level systemic change that happens over a couple of decades. The Yeoville Studio is anchored in architecture, art, photography, and town planning. It needs economists, statisticians, educational theorists and financial analysts.

At the time of the work of the Yeoville Studio they did produce some handy fold out guides to Yeoville’s architecture, its restaurants, music, arts and so on. Great effort went into promoting tourism. Those small guides are already quite collectable.

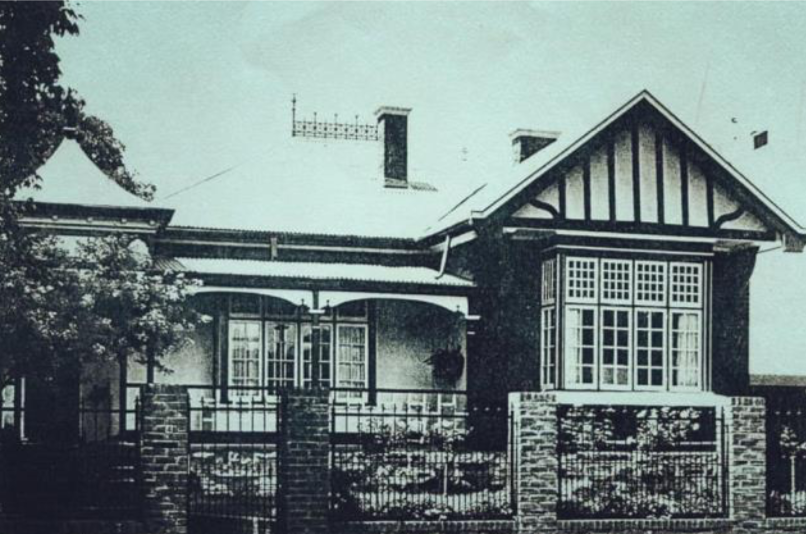

To understand the present, the history of a place must be probed and explained. There is very little attempt to understand or document the history of Yeoville over a century. There is heritage in Yeoville and in 2021 I am sadly watching its disappearance. The people who live in Yeoville today are the inheritors of the architecture and the infrastructure created and shaped generations ago.

House Hains, one of the oldest buildings in Yeoville (1891)

For so many people Yeoville is simply a point of arrival in the city and then a point of departure to escape the grime and deepening decay of the suburb. The book says something of the people who left but one feels that those who stay in Yeoville would also like to leave. I was intrigued that Clive and Ivor Chipkin should have been interviewed. Clive was born and grew up in Yeoville when there was a large Jewish community; but he left Yeoville and moved on to Craighall Park. I like the idea of asking the interviewees to draw maps of their Yeoville, but this research just scratches the surface of memory. Others have moved on to Emmarentia, Melville, Parkhurst, Kensington - what about the history of the people who have lived in Yeoville for 50 or 60 years? Why is this suburb a place of transit?

Clive Chipkin (Kathy Munro)

The ‘frozen moment in time’ feel of this book came through in one single photo of The Ridge which in 2010 was an open air grassed Ridge view site loved by sightseers, film makers and people who gathered to pray and worship. The caption explains, “the Ridge marks the border between Yeoville and the denser neighbourhoods of Hillbrow and Berea” and adds that this photo was selected as one of the best representations of Yeoville by residents during a 2010 public exhibition. A decade later that land has been purchased and a popular and powerful church has taken possession to exclude the Yeoville populace. They plan to build a church for thousands on the ridge and so destroy what had become an open air green lung and common land. Yeoville is changing yet again. Today too there is an imminent crisis in the failed so-called Corridor of Freedom city project that pushed public investment into a rapid bus transport system that some six years after construction commenced is not yet functioning. Louis Botha now cuts Yeoville off from most of Upper Houghton and is more and more of a ghetto defined by poverty, overcrowding and massive social problems.

The famous view site (The Heritage Portal)

I wish I could say that the Yeoville Studio accomplished great things for Yeoville, but this type of project is far more likely to have an impact on the lives of the students as participants and the careers of researchers. A successful book has been delivered and the contributing students can notch up their first printed publication. One can only hope that the students moved on to careers in local government, perhaps working in and for the city of Johannesburg and continuing with the goal of achieving sustained and long term changes in the city. We need more Wits trained planners to work for the city with the long term good of society as the driving force of the policy makers. How can people be empowered to improve their physical environment? The essential questions have to be around work, employment opportunities, and an education to equip people to be able to do more with their lives than be street traders on collapsing pavements, with water from over used collapsing infrastructure flowing freely in the streets, whilst passing cars navigate deep potholes.

In summary the book is itself a teaching tool and offers a method of student engagement in a real life social laboratory. It also adds and enriches Johannesburg literature. Claire Benit-Gbaffou has returned to France and left a huge void. Published by Wits University Press, this book is the companion volume to Changing Space, Changing City. Johannesburg after Apartheid which I reviewed a few years ago (click here to view).

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.