Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

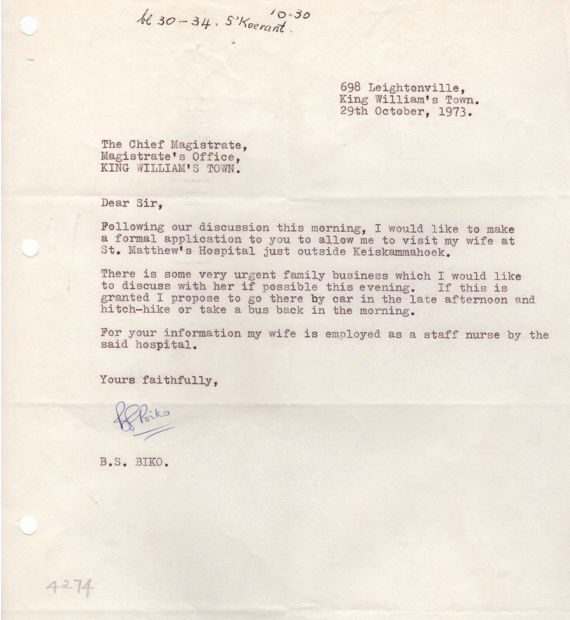

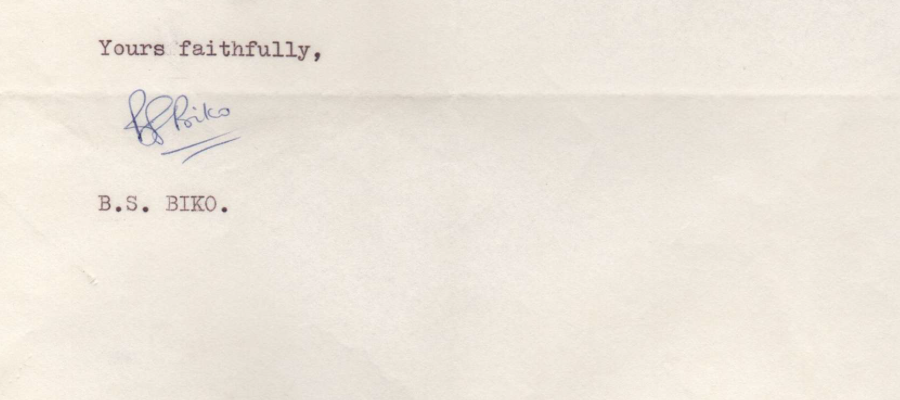

In October 2017 it was brought to SAHRA’s attention that a letter written by Steve Biko was going to be auctioned online in Britain. The letter was addressed to the Magistrate in East London, South Africa, and details a request to leave the magisterial district under which Biko was restricted in order to visit his wife. Steve Biko, the leader of the South African Student Organisation (SASO); and intellectual inspiration behind the Black Consciousness Movement, was known for being a prolific writer of letters. The South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), mandated to identify and conserve South African heritage Resources, approached the auction house concerned to enquire how the letter left South Africa and to inform them that in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act, No. 25 of 1999 (NHRA) and described in the List of Types of Objects, Gazetted in December 2002 (currently under review), objects associated with leaders and events in South Africa are protected and may not be exported without a permit from SAHRA. The auction house was not co-operative, and because their advert did not include the name of the “owner” of the letter, it was impossible for SAHRA to adequately deal with the matter. It is also likely, that the letter had been illegally exported. However, the key question is, how a letter addressed to the Magistrate that ultimately belongs to the State, ended up in private ownership?

The Biko Letter sold by International Autograph Auctions

Instances such as this are still far too common an occurrence in South Africa, with objects associated with significant South Africans, being exported without following due process and frequently illicitly trafficked. This particular case exemplifies perhaps, the vulnerability of objects such as these especially because it was written to the Magistrate and belongs to the State, yet it ended up in private ownership and was sold online to the highest bidder. It highlights the need for more concerted efforts for heightened awareness and interconnectedness between SAHRA, the public, South African Museums; the National Archives, State Institutions, Auction houses as well as Customs and Excise officials.

When considering the notion of leadership or leadership figures, most people intuitively have some basic ideas which come to mind. Leaders are thought to be strong personable figures who command the respect of their peers and those around them. Often, people think of leaders as political figures who drive various initiatives on an international, national, provincial level, or within local communities. Whilst many may not consider leaders in this fashion, it is certainly something that needs further investigation moving forward.

To begin with, it is important to consider the following quote by Afsaneh Nahavandi, “There are no leaders without followers”.

Leadership is, by its very definition, an interplay between the roles of the respective leader, and those who follow them. A leader must provide guidance to validate the actions and belief structure of their followers in order to, not only best represent their needs and interests, but also to guide them towards a shared common goal.

A leader therefore, must be able to capture the imaginations and desires of a group of people and be able to express those on a public platform. In doing so, a sense of community is created whereby people within that given community can share their ambitions and work towards a common desired end; the leader will help to facilitate and guide this process forward.

Any discussion about a given leader must, by its very definition, also be a discussion about those who follow them.

Section 3.5 of the provisional List of Types of Heritage Objects (gazetted on the 24th of August of this year, that was available for public comment), states that “Objects related to significant political processes, events, figures and leaders in South Africa” are considered to be heritage objects with regards to the precepts outlined in the National Heritage Resources Act.

Perhaps the best way to think of leadership and leaders, may be to consider those figures, who, through their actions, have had the largest impact on South African history, whether favourable or unfavourable.

This is, however, a broader issue, and this article aims to delve into conceptualisations around leadership and how interconnectedness between SAHRA and South African Museums can help to benefit the sector and thereby ensure that heritage resources that belong to the State and form part of the national estate are preserved for future generations.

It also attempts to identify the complexities in identifying leaders of national importance and how best to protect and preserve objects associated with them in a holistic approach drawing upon museums, State institutions and the private sector.

To begin, let us introduce two seemingly disparate examples of famous South African leaders, with some surprising similarities, whose spheres of influence were very large indeed.

Jan Smuts

Smuts, after excelling in studies both at the University of the Cape of Good Hope (UNISA) and at Cambridge University, occupied a prominent advisory position on the Executive Council in the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek under President Paul Kruger in 1897. He then proved himself as a superb military strategist as a commander of the Boer forces during the Anglo-Boer War; and later in the First World War through combat in German South-West Africa. He was also instrumental in the formation of the British Royal Airforce (RAF) and was a draftsman of and signatory to the Covenant of the League of Nations - an achievement he would later replicate during the founding of the United Nations.

Smuts photographed at the San Francisco Conference where the United Nations was established (Smuts House Museum)

Smuts became Prime Minster of the Union of South Africa after the death of Louis Botha in 1919 and again in 1939 after JBM Hertzog was deposed as Prime Minister; this paved the way for South African involvement in the Second World War (the War). During the War, Smuts was promoted to the rank of Field Marshall of the British forces and served as a close advisor to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. After the war Smuts saw a sharp decline in his support at home due to his constant involvement in international affairs and absenteeism locally. At this point, Smuts had a greater following and support base internationally than he did in South Africa, and this resulted in him losing the 1948 election to D.F Malan. Smuts passed away two years later at his home in Irene on the 16th of September 1950.

Smuts House Irene (The Heritage Portal)

Nelson Mandela

Born Rolihlahla Mandela and named “Nelson” by a teacher at his primary school in Qunu in the Eastern Cape.

Mandela completed degrees at UNISA, Fort Hare and WITS University before he co-founded the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) and in 1951 was elected as its President. Ten years later, Mandela joined Umkhonto weSizwe, the military wing of the ANC that he was instrumental in forming and in 1963 was charged with terrorism and treason by the Apartheid Government. As part of his submission before the court at the Rivonia Trial, Mandela delivered a powerful and influential speech outlining his hopes for “the ideal of a democratic and free society”. The documents related to the trial were subsequently “owned” by Percy Yutar, the Prosecutor in the trial and were offered for sale to the highest bidder. It is not known how these State-owned documents ended up in private ownership.

Mandela spent 18 years imprisoned on Robben Island, and subsequently a further 8 years collectively at Pollsmoor and Victor Verster Prisons, before the unbanning of the ANC and his release from prison in 1990. In 1993 Mandela was jointly awarded the Nobel peace prize with then President F.W de Klerk. After South Africa’s first free democratic election in 1994, Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first President of a democratic South Africa.

Mandela’s sway and influence were instrumental in the peaceful transition of power in South Africa. Madiba was already an international icon whilst imprisoned which was enhanced prior to and during his tenure as President and given the national and international support annually for Nelson Mandela Day on 14 July after his death, his stature and significance keeps on growing as it inspires new generations. This sets him apart from Smuts.

Mandela Statue at the Union Buildings (The Heritage Portal)

Despite their differences, Smuts and Mandela hold some similarities and interconnected themes. Both were national leaders during difficult periods in South Africa’s history; both were, at one point in their lives, involved in armed resistance against a dominant power; both were qualified lawyers and spent part of their academic careers at the same institution; both won significant international acclaim and are honoured with statues in the Parliament Square Garden in London opposite the British Houses of Parliament (The Smuts and Mandela statues were unveiled in 1956 and in 2007, respectively). Lastly, Smuts and Mandela are the only two individuals/leaders who have collections associated with them specifically declared (although the declaration of the collection associated with Mandela is still being finalised by SAHRA).

Although the stories of each of the figures presented here may vary widely in their details, they all had an influential role to play, and in the enactment of these roles, we can find commonalities. It is through these common threads that we, with the benefit of hindsight, may be able to weave a complex holistic picture of our shared past.

Non political figures

Despite the seemingly intuitive notion that leaders and important figures are, by default, political in nature this is certainly not the case. Generally, far too little exposure and importance has been ascribed to other kinds of leaders; leaders in the visual, written and performing arts, leaders in the fields of science, technology and medicine and lastly significant entrepreneurs and business people.

To date, the importance of these figures has been largely underplayed in terms of official recognition. Many of these figures are household names across South Africa, cutting through racial, cultural, religious, gender and class divides, as well as generational divides. Some could be thought to contribute to a shared South African identity and may constitute part of what it means to be a South African. This being the case, it is important that these figures are afforded the recognition which they deserve.

How do we define other leaders and innovators?

The NHRA does not define a leader but makes provision for protection of objects associated with leaders. As a means to define a leader, this article, draws from Section 3.3 of the NHRA & 3.5 and 3.6 of the provisional List of Types (gazetted 24 August 2018) and suggests the following towards this end: Individuals who, through their actions or through one or more aspects of their work, have contributed something of significance to the South African cultural, technological or scientific landscape.

The definition above is left intentionally broad to allow for the sweeping range of potential influences and contributions.

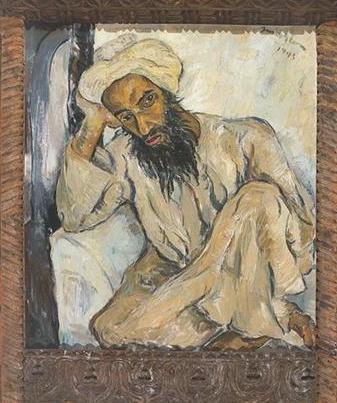

Some artists have been afforded their deserved recognition; for example, Irma Stern, Gerard Sekoto, Pierneef, Walter Battiss, Peter Magubane, Alf Khumalo, Esther Mahlangu, and many others whose works over the last few years have become highly desirable and sought after internationally. Bonhams Auction house in London created an international market for South African artworks by hosting a twice annual auction of South African art since 2007, and in March 2011, Irma Stern’s “Arab Priest” painting sold for a record R34.3 million. (The painting, owned by the Qatar Museums Authority (QMA), loaned to QMA for twenty years under certain conditions, is due to return to South Africa for a period of one year in 2019, and the process is being facilitated by SAHRA). Despite a few notable exceptions there has been very little recognition of the contributions to South Africa of many important figures spanning a wide range of disciplines.

Irma Stern’s “Arab Priest”

Section 3.6 of the provisional List of Types of Heritage Objects states: “Objects related to significant South Africans including writers, artists, scientists, and events of national importance” are considered to be heritage objects with regards to the precepts outlined in the National Heritage Resources Act.

Miriam Makeba

Miriam Makeba, born in Johannesburg in 1932, began her music career in 1954. After flying to Venice to receive a Grammy award in 1965, for her singing role in the documentary “Come Back Africa”, (the first South African to receive a Grammy Award), Makeba spoke out about life under the Apartheid Government and as a result her passport was revoked, forcing her into exile for 30 years. She later made two submissions to the United Nations regarding the unjustified imprisonment of opposition leaders in South Africa.

Her musical career took off when she moved to the United States in the 1960s performing with the likes of Harry Belafonte. With her increased fame and public platform, coupled with rising tensions in South Africa after the Sharpeville Massacre, Makeba used her platform to become an increasingly outspoken critic of the Apartheid Government. Makeba was not alone in the performance of resistance music on an international level, with others, including the likes of Lucky Dube, Brenda Fassie, Hugh Masekela and Johnny Clegg.

Throughout her career, Makeba recorded songs in a range of different languages; her most successful however, were those recorded in her mother tongue, Xhosa, including Pata Pata, that became known as the Click Song. One of her greatest legacies is that she popularised the African idiom in music on an international level.

Miriam Makeba (Paul Weinberg)

//Kabbo; Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd

Wilhelm Bleek, born in Berlin in 1827, completed his PhD in Linguistics in 1851. In 1862, after moving to Cape Town, he married Jemima Lloyd. They moved to a residence in Mowbray and Jemima’s sister, Lucy Lloyd moved in with them and became Bleek’s colleague. In 1870 Bleek and Lloyd start working together on a project to learn the /xam language. The following year //Kabbo was allowed to leave the Break Water prison in Cape Town, and moved into Bleek and Lloyd’s residence in Mowbray, and he became their first teacher. During the years that followed between 1871 and 1875, Bleek and Lloyd wrote down and codified the /xam language, starting with lists of words and linguistic sounds, to eventually documenting life stories, history, folklore and customs and beliefs. Upon Bleek’s death in 1875, Lucy Lloyd continued to transcribe stories and mythologies of the /xam people, and later also of the !kung, with the last record of work with any informants conducted in 1884.

Today the Bleek and Lloyd archive resides at the University of Cape Town. The anthropological and historic value of the collection is unrivaled. It is evident that the record and archives were produced as the result of a deep mutual respect and co-operation between Bleek and Lloyd on the one hand, and //Kabbo and the other /xam and !kung informants, on the other. Over and above the value and significance of the archive itself, being one of the most cited archival references in Southern African anthropology and archaeology, the documents stand as a testament to the interpersonal relationships upon which they were built.

As with the discussion around political leaders, these two examples serve to illustrate that the contributions of the people mentioned are vastly different, yet even here, common threads can be found. In many ways it should be lamented that many such contributors to our understanding of our shared history have yet to be adequately recognized.

SAHRIS: A tool for connectivity

The use of the South African Heritage Resources Information System (SAHRIS), as a standardised archival tool for the inventorising of collections, can facilitate a marked improvement in the connectedness of museums and the heritage authorities. Such a process would not only enhance the knowledge of South African collections with a more comprehensive inventory of the National Estate but would also facilitate a vast improvement in the management of collections in museums as well as their access to and inclusion of information and knowledge on significance produced by SAHRA to enhance exhibitions. It is important here to note that SAHRA is striving to improve the inventorisation system available on SAHRIS, to provide the most value to museums in order to conduct and compile such inventories. SAHRA is aware that there is always room for improvement of such systems, and through liaison with SAHRA’s National Inventory Unit, is more than willing to have a dialogue with museums or institutions wishing to use the system in order that it can best serve the needs of the museum community.

If all museums were using SAHRIS, we could start linking collections associated with an individual or leader and create meta-collections. This would not only facilitate the communication of experiences of one institution with a given collection to an associated collection in another institution, but also allow for an assessment to be conducted that spans the full gamut of objects relating to a significant person. This would help with regards to declaration of objects/collections, but also to ensure that those items that form part of the National Estate which are declared by SAHRA, are the most important objects which collectively tell a complete story. In the instance where such a declaration or serial declaration may span two or more institutions, those institutions would then be able to draw upon their sister collections in order to facilitate the displays and narratives surrounding their own collection.

Let us use the whereabouts of each item of clothing associated with Madiba as an example (this is largely unknown to SAHRA with the exception of the Springbok Rugby Jersey housed at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg). For the purposes of this example, we will assume that each of these items is housed in a different museum. If in this instance, all of these museums have their collections inventorised on SAHRIS, SAHRA and South African Museums would be able to access these objects in the digital records of the respective institutions and, in the case of SAHRA, potentially declare such a collection, or, in the case of museums, be able to curate exhibitions at each institution simultaneously drawing upon the collections of their sister museums. It should be noted that such types of meta-collections would also not be restricted to objects associated with one individual but may span a range of people connected by a common theme.

In conclusion, in the situation where Museums and heritage institutions across South Africa were all using SAHRIS for their digital inventories, this comprehensive database would enable SAHRA to more accurately track the movement of heritage objects. This would also significantly aid SAHRA in the fight against the illicit trafficking of heritage objects out of the country, and may even prevent future loss of such significant objects as the signed letter by Steven Biko mentioned at the beginning of this article.

This article emanates from a paper presented by Cuan Hahndieck at the South African Museum Association (SAMA) Conference held on 22 – 22 October 2018. The paper, written by Cuan Hahndiek and Regina Isaacs was titled, Leadership and Interconnectivity: leadership and the role SAHRA can play to facilitate connectivity between museums. Cuan was awarded the President’s Award for the best paper given by a first-time speaker at a SAMA conference.

References:

- Bank, A. 2006; Bushmen in a Victorian World, South Africa, Double Story Books.

- Deacon, J & Dowson, A (eds) 1996; Voices from the Past: /Xam Bushmen and the Bleek and Lloyd Collection. South Africa, Witwatersrand University Press.

- Deacon, J & Foster, C. 2005; My heart Stands on the Hill. South Africa, Struik Publishers.

- Rassool, C. 2004; The Individual, Auto/biography and History in South Africa, unpublished PhD dissertation, South Africa, University of the Western Cape.

- Skotnes, P. (ed) 2007; Claim to the Country: The archive of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. South Africa, Jacana Media.

- Steyn, R. 2015; Jan Smuts: Unafraid of Greatness. South African, Jonathan Ball publishers.

- www.nelsonmandela.org

- www.sahistory.org.za

- www.miriammakeba.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.