This book is a superb scholarly study of a little known aspect of the Mohandas Gandhi story in South Africa. It tackles the subject of running a printing press and spreading the message of Satyagraha or passive resistance through the medium of the printed word. This was the acorn that yielded a giant oak and bore fruit albeit with tragic costs and consequences with the achievement of Indian independence in 1947. The shaping of Gandhi’s political ideas and strategy took place in South Africa and was honed on the almost impossible and at times futile struggle for Indian political rights in South Africa between 1903 and 1914. 1914 was the year when Gandhi returned to India believing that his work in South Africa had been completed; his mission thereafter was the greater cause of fighting for Indian independence.

Gandhi lived in this Troyeville house from 1904-1906 (The Heritage Portal)

Hofmeyr writes with flair, style and erudition. Her research fits into literary textual analysis and the field of literary criticism but her writing is accessible and readable for the “non-academic but interested in Gandhi” type of readership. She is a professor at Wits University and a key person in the creation of the Centre for Indian Studies in Africa, located in the William Cullen Library at Wits.

The Centre for Indian Studies is located at the William Cullen Library at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

This book adds to scholarship because the research is based on meticulous documentation and asks perceptive questions. You can skim or skip the cross references to other writers or use the careful footnotes as a guide to the wider literature and so become hooked on Gandhi studies. I found this book a pleasure to read. I was introduced to another dimension of the Gandhi story in South Africa. Because Gandhi became an international political figure of the 20th century, his early years in South Africa where he shaped and sharpened and intellectualised but also made practical his resistance tactics are of considerable relevance in international scholarship.

Satyagraha House in Orchards where Gandhi lived with his friend Herman Kallenbach in 1908 and 1909 (The Heritage Portal)

Hofmeyr is interested in the intellectual roots of Gandhi’s thinking. Her focus is on the Gandhian textual culture that grew up after 1898 in Durban where Gandhi established his International Printing Press. The purpose of a private press was to print pamphlets, periodicals and a newspaper. The objective was to educate and shape public opinion in support of the struggle for Indian rights led by Gandhi.

The campaigns and protest to effect changes in the laws around the recognition of Indian rights in Natal and the Transvaal needed to be backed by rational argument and writing about the cause and so spreading the news. Ultimately, the mammoth task of starting a printing press and maintaining it was of relevance in the Indian struggles in the broader British Empire. Of course writing assumed a literate readership. The assumed subscriber to the Indian Opinion (founded 1903 and published until 1962) had to be literate and reasonably educated to follow the complex arguments. It was not really a periodical for the masses. Here I would have liked more discussion about the spread of literacy among Indians in South Africa circa 1906, and an assessment of educational capacities and resources. We need an assessment of whether Gandhi was right in his assumptions about who would read his message. Was the satyagrahi or fellow passive resister as literate, articulate and as passionate as Gandhi believed? Could all classes and economic categories be reached through the printed word? I somehow suspect that Gandhi saw his followers in his own image and perhaps this is why he was drawn to Johannesburg and the Transvaal community - who were more likely to be professional men and traders. His experiment in writing, printing and proselytising were all facets of his political campaign.

However, there was also another element to this “experiment “in printing. Assuming that there were readers out there, Gandhi saw reading as a slow activity, in the sense that reading required concentration, personal engagement, time, thought, reflection and effort. The message conveyed in a text needed to be understood as a deep-brain function. To really understand (and be convinced by) the message the ideal reader needed to read and reflect and so become a partner in Gandhi’s enterprise. This perfect reader was a slow reader and reading according to Gandhi was an exercise that swung the reader into a commitment to the cause. Gandhi’s view was that the human brain could only go at its own pace to read, absorb, and understand the printed word; there was no industrial approach to reading if a person wished to achieve intellectual independence.

It was also a commitment to emerging nationalism within the framework of the British Empire. For Gandhi the challenge was how to be a nationalist within the great British Empire that at the turn of the 20th century was at its height and expected loyalty to Queen and King, when local politics in different parts of that Empire (including South Africa) applied discriminatory policies to these “British subjects” of different races. How could one be true to one’s own identity, fight for dignity and human rights and also find a destiny that ultimately spelt independence for India? There were no simple answers and it was a long slow, tortuous path to 1947 and the departure of Britain from India. This is a book that explains the early years of the journey.

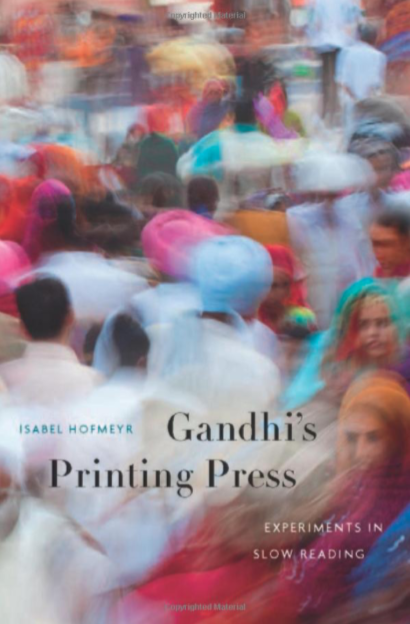

Book Cover

The South African experience was a critical and formative part of shaping the tactics and underlying philosophy that sought to fight for the rights of Indians in the British Empire. Owning, and applying a printing press as a weapon became part of the passive resistance armoury. Gandhi, the immigrant lawyer to Natal, later migrant to the Transvaal, turned into a propagandist, philosopher, writer, thinker, journalist and politician armed with the printed word. He wrote to sell his ideas and to draw people into his world.

Indian Opinion became the primary vehicle. It commenced publication in 1903. It was printed by the International Printing Press initially in Durban but some 18 months later, the Press moved to Phoenix, the Gandhian led and financed alternative settlement, 14 miles north of the city. It was Gandhi’s first ashram. It was also inspired by Tolstoy’s ideas and Tolstoy farm was the Transvaal creation a few years later, a settlement funded by the Lithuanian architect Hermann Kallenbach.

Statue of Gandhi and Kallenbach in Lithuania (Martynas Ambrazas)

Hofmeyr explains that both the press and Indian Opinion became protagonists in the larger story of Satyagraha in South Africa as it unfolded between 1906 and 1914. Hofmeyr is particularly strong in engaging the world of Gandhi with all its quirkiness, deep philosophising, a lifestyle of vegetarianism, and a pre-industrial approach to living and production. Gandhi’s community brought people of all backgrounds to live a life of abstemiousness, asceticism and as Hofmeyr calls it, “slow reading“.

The International Printing press offered printing services in ten languages and seven different scripts. That alone was a remarkable feat for the period. Indian Opinion initially appeared in four languages (English Gujarati, Tamil and Hindi.) It was more than a newspaper, it was a journal, a periodical and a political tract. All print vehicles and media were enlisted to convey the message.

I found myself wondering who the readers were, who the advertisers in this journal hoped to reach and what the extent of the distribution was. All difficult questions to answer but did Gandhi ever ponder these questions? Gandhi was never the editor of Indian Opinion (the first editor was Sjt Mansukhlal) but he was the primary writer, journalist, columnist or as Hofmeyr calls him “the text maker”. I also wondered about the finances behind the journal and the press. This seems to be a fairly opaque area perhaps because the accounts and finance archives are not the easiest to find. Gandhi himself in his autobiography hints at financial disaster looming, (I rather think that must have been a chronic condition) but that to stop publication would have been “a loss and a disgrace”. I think he meant he did not want to lose face and goes on to explain that he sank his savings into the enterprise and remitted £75 each month to ensure the journal and press continued. Gandhi explains that between 1904 and 1914 (excluding periods of enforced rest in prison) “there was hardly an issue of Indian Opinion without an article from me” (p 348: An Autobiography, 1948 reprint). Gandhi never believed in copyright or in the limitations of print capitalism. Conveying and spreading ideas was what brought convert and supporters into the fold.

It is difficult to judge the effectiveness and power of all Gandhi’s writing at the time - was he not talking to the converted and was it not in retrospect and following a long gestation period that the Gandhian philosophy gained international influence? There is some irony in the appearance of Gandhi (like Mandela) on the banknotes of the Central bank of India today; a bank note is another form of printing that speaks to all of the capitalist infrastructure so opposed by Gandhi. Gandhi’s autobiography was published as an edition of only 6000 in 1927 and it was not until reprinted in 1948 (the year of Gandhi’s assassination) that the print run was 15 000.

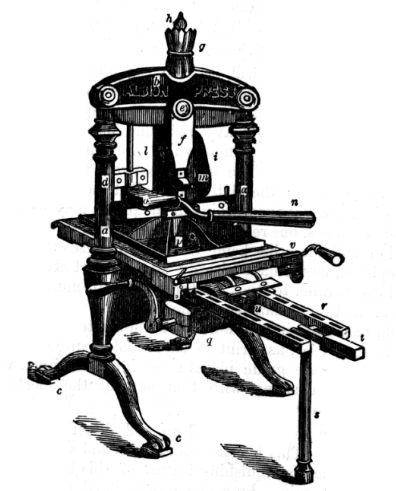

Gandhi’s printing press at Phoenix was an Albion Press and a Platten jobbing Press. These were the workhorses of the printing industry. Albions were imported presses from England, and operated on a hand-printing basis. The Albion press was originally designed and manufactured in London in 1820. It worked by a simple toggle action. Albions continued to be manufactured, in a range of sizes, until the 1930s (details from the Paekakariki press website). Quite a number of Albions came to South Africa, particularly to the missionary presses. You can see an Albion Press in Johannesburg if you connect with and make an appointment with imPRESSed Sudio & Museum in Melrose (click here for details).

Image of an early Albion press (Paekakariki Press of London)

Albion Printing press at imPRESSed Sudio & Museum

The subject of the history of printing in South Africa has been studied by Anna Smith and by L J Picton (see for example, L J Picton: Weslayan Mission Presses and the Xhosa Bible (1982) and Anna Smith: The Spread of Printing, Eastern Hemisphere, South Africa (1971)). Anna Smith, although she discussed the development of printing in Natal, did not discuss Gandhi’s efforts in Durban or Phoenix. Martin Ciolkosz makes point that printing historians in South Africa are either interested in the “who and where” or in the “what and how” and it is for this reason alone that Hofmeyr’s study also makes a unique contribution to the study of printing history in South Africa and adds to the literature.

Printing presses make an interesting case study in industrialization, British 19th century engineering excellence as well as the spread of literacy. There is a link between the the widening reach of the printed word and the power of ideas. Ultimately it was the power of ideas and their propagation into popular culture that undermined the British Empire.

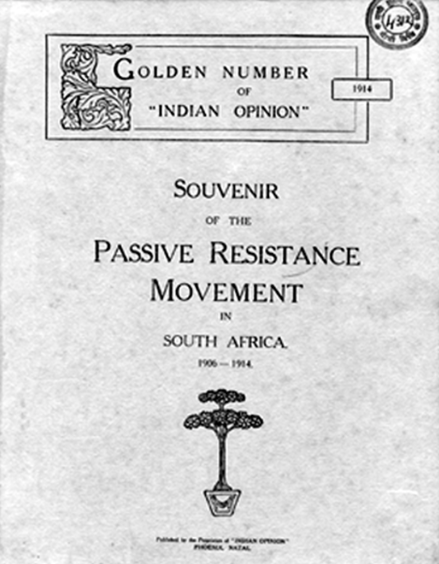

An issue of Indian Opinion that I have found particularly fascinating is the Golden Number of Indian Opinion published in 1914 as a Souvenir of the Passive Resistance Movement in South Africa 1906-1914; it was published in English and Gujarati. It carries a piece by Gandhi on 'The Theory and Practice of Passive Resistance', Gandhi’s speech at the farewell 1914 Johannesburg banquet, as well as a letter from Tolstoy on the subject of passive resistance, written in 1910 in Russian and translated into English in Johannesburg. Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau were Gandhi’s role models and inspiration. In a way what he wanted was a retreat from industrialism and a reversion to a much simpler community life - the ashram model.

Golden Number of Indian Opinion

Perhaps Gandhi’s most important work on Indian politics was Hind Swaraj (or Home Rule). And Hofmeyr explains how this work was addressed to the reader of Indian Opinion (assumed to be a male). It first appeared in two instalments in Indian Opinion in Gujarati in December 1909 and was translated into English by Gandhi himself in 1910. It was published in book form by the International Printing Press under the title, Indian Home Rule. Hofmeyr probes further and shares her insight that Hind Swaraj took on a different life and meaning in later years and how the imagined Reader changed from the passive resister in South Africa to the revolutionary firebrand in India.

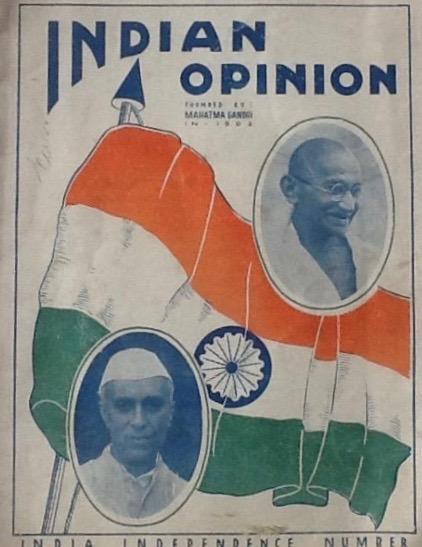

Another later but as fascinating issue of Indian Opinion that has come into my own collection is the India Independence Number, 15th August 1947. The cover notes that this periodical was founded by Mahatma Gandhi in 1903. The editor by 1947 was Manilal Gandhi (the second son of Gandhi and his wife Kasturbai, who became editor in 1920, and who was the longest serving editor of Indian Opinion; his dates 1892-1956). The issue carried messages from Field Marshall the Rt Hon. J C Smuts (Prime Minister of South Africa) and the political opponent of Gandhi during his South African years. There is also a message from the High Commissioner for the United Kingdom in the Union of South Africa, Evelyn Baring (in office 1944–1951). There is a certain irony in the wheel of time passing and that the Press and political voice of Indians in South Africa should have been started by Gandhi in 1903 and survived to celebrate Indian independence. Gandhi was assassinated in January 1948 and in South Africa Smuts lost the General election in May 1948. The need for voice and a printed medium for Indians in South Africa was needed more than ever as the National Party came to power. Real independence in South Africa would need to wait for another 40 odd years. Indian Opinion ceased publication in 1962.

India Independence Number edition

Gandhi commented that the Satyagraha movement that he founded would have been impossible without the Indian Opinion. Hofmeyr puts all of Gandhi’s printing efforts and his textual experiments in his periodicals and pamphlets into a context. The author adds an important insight into the literature on passive resistance by seeing reading as an allegory for Satyagraha.

This book adds significantly to the literature on Gandhi, written by a fine, insightful literary scholar.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters and is well known for her magnificent book reviews. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials.