I recently added a new title to my library, an old book with the quaint title of "A Winter Tour of South Africa". This is a first edition, published in London in 1890. It is an account of travels through South Africa by the distinguished writer and traveller, Fredrick Young. Young's adventure occurred after gold and diamonds had been discovered but when old rural lifestyles remained with the majority of the population living on farms and in small dorps. The winter in the title is the South African winter months of 1889 and the journey was a leisurely one moving at the pace of an ox wagon or by slow railway. Young really had the time to get to know the country by talking to influential people as well as those odd characters one meets en route. Here is a fascinating account of what South Africa was like in 1889.

Book Cover

Young wrote about his series of journeys within a larger expedition, through what was then wide open veld that stretched as far as Bechuanaland (modern day Botswana ). South Africa was at peace in 1889 and paused between wars. The first Anglo Boer War was still within recent living memory as was the Zulu War of 1879 but the turmoil and disaster of the second Anglo Boer War was still a decade away. The losses of British troops at Laings Neck and Majuba under the inept leadership of General Colley were raw and bitter in recent memory. For Young it was the blood and sacrifice of the British soldier that created an empire.

Nonetheless, 1889 was a time of hope when you shot a springbok for your dinner and commented on your disappointment at the paucity of game. The hunting frontier was shrinking. Southern Africa's political structure was still fragmented with the two fiercely independent, somewhat wild Boer Republics lying beyond the 'civilized' coastal British colonies of the Cape and Natal. The real frontier for Young was Bechuanaland which he thought was just ripe for colonization and a natural part of South Africa. Young had a vision and his book is both a travelogue and a tract for his ideas about a colonial empire spreading the British imperial model north through Africa. He carried the flag and a message for Queen Victoria, under the auspices of the Royal Colonial Institute, that railways, sanitation and enlightened politics would bring unification, confederation, successful political management and peace. Young was of the view that the British government had mismanaged South African affairs for the previous 25 years yet strangely he makes no mention of Cecil Rhodes who was the rising politician of the time and became Cape Prime Minister in 1890. Rhodes succeeded Gordon Sprigg who was Prime Minister in 1889.

The Royal Colonial Institute was founded in 1868 and went through a series of name changes. By 1889 it saw itself as an important shaper of colonial and imperial policies and had acquired a Royal Charter which gave it the status and appearance of authority. It was well supported and prior to the Second World War built up an imposing library at its Northumberland Street headquarters. It was an organization that preached reasonableness, enlightenment, peace and the value of political unity under the British Empire. It was regarded as a progressive organization giving early admission to women, Asians and Africans! When decolonization came along and Britain lost the willpower and economic resources to paint the globe red, the society sank into irrelevance as the Royal Commonwealth Society. Its great library was sold to Cambridge University and its headquarters were sold off to pay debts. Today, the focus of the Royal Commonwealth Society is on charitable work to improve the lives of the citizens of Commonwealth states through education, outreach and youth programmes.

Young was a man of 72 when he undertook his African journey. It could not have been fun all the time bumping along on wagon tracks at the pace of an ox. There must have been many hours of boredom. In his lifetime he was known as a "British traveller"; he visited and wrote about Canada, Greece, South Africa and Turkey. Wikipedia describes him as a trader but clearly what motivated this gentleman traveller was his work for the Royal Colonial institute. His papers are held by the Library of Cambridge University.

Sir Frederick Young was a KCMG and indeed he made much his title and status (Sir Frederick KCMG is imprinted on the cover). The KCMG stands for Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George and is an Honour conferred by the British monarch. This is the context for understanding the world of Young. His was a Victorian imperial perspective when the Queen was Empress of India and the 1887 Golden Jubilee had been a triumph of confidence and an expression of British monarchical authority.

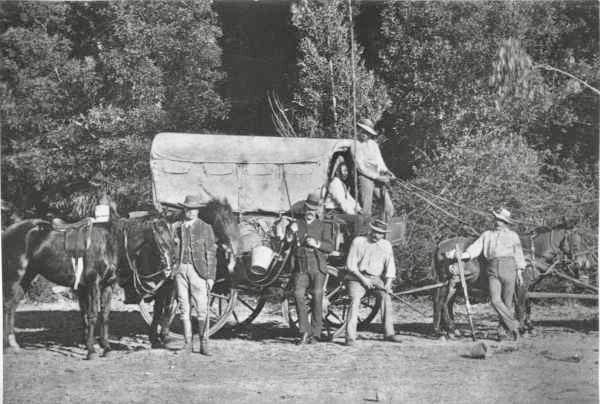

Young provides some fascinating vignettes of the towns he visited; starting with Cape Town, then Kimberley, Klerksdorp, Potchefstroom, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Maritzburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and Grahamstown. Where there was no railway line, travel with a party of all male friends was by wagon. The journey turned into an adventure around a campfire under the dark, starry African sky. Everyone encountered regardless of colour or language was welcoming and hospitable. Durban to Port Elizabeth was a coastal journey by steam ship but then back inland by rail to the junction at De Aar and the return journey to Cape Town.

Travelling by wagon

In 1889 it took 42 hours to travel by rail from Cape Town to Kimberley, a journey of between 600 and 700 miles. At that time Kimberley had a population of 16 000 people (6000 whites and 10 000 blacks). There's a thumbnail sketch of De Beers' diamond mining operations but the effect of Rhodes' creation of a monopoly in diamond mining eludes the author. Kimberley was the railway terminus and from there onwards it was wagon travel into pioneering country.

Here is a wonderful account of what Johannesburg was like in 1889 and it's my pleasure to reproduce the entire chapter on Johannesburg. It's a delight to savour Young 's account of what he calls this "auriferous town".

We had some little trouble in finding our way into the town, as for the last two hours the daylight failed, and we had to grope our way along at a snail's pace in total darkness. This, in a country of such rough roads and deep and dangerous gulleys and water-courses, was a most intricate and difficult proceeding. Eventually, however, we reached our destination about nine o'clock at night.

This "auriferous" town is indeed a marvellous place, lying on the crest of a hill at an elevation of 5,000 feet above the level of the sea. Along its sides are spread out every variety of habitation, from the substantial brick and stone structures, which are being erected with extraordinary rapidity, to the multitude of galvanised iron dwellings, and the still not unfrequent tents of the first, and last comers. It is indeed a wonderful and bewildering sight to view it from the opposite hill across the intervening valley. Scarcely more than two years have elapsed since this town of twenty-five thousand inhabitants commenced its miraculous existence. The excitement and bustle of the motley crowd of gold seekers and gold finders is tremendous, the whole of the live-long day. The incessant subject of all conversation is gold, gold, gold. It is in all their thoughts, excepting, perhaps, a too liberal thought of drink. The people of Johannesburg think of gold; they talk of gold; they dream of gold. I believe if they could they would eat and drink gold. But, demoralising as this is to a vast number of those, who are in the vortex of the daily doings of this remarkable place, the startling fact is only too apparent to anyone who visits Johannesburg. It is to be hoped that the day will come when the legitimate pursuit of wealth will be followed in a less excitable, and a more calm and decorous manner, than at present regretably prevails.

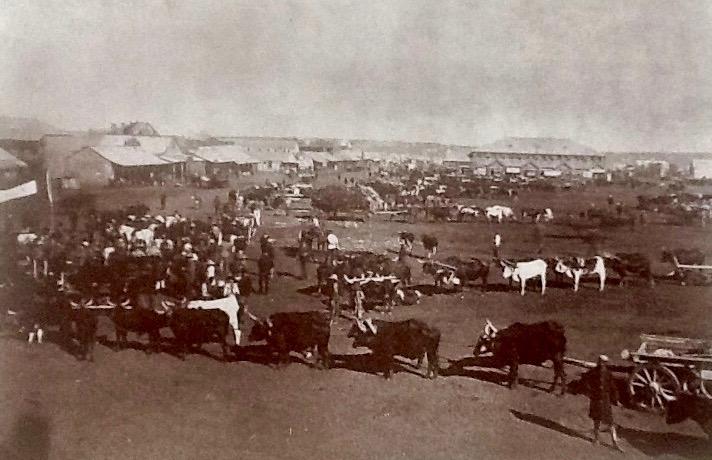

I spent a pleasant, as well as interesting, week at Johannesburg; and, during my stay, visited several of the mines, among them Knight's, the Jumpers, Robinson's, Langlaagte. At Robinson's I had an opportunity of inspecting the wonderful battery just completed, and in full working order, constructed on the most approved principles for gold crushing, with sixty head of stamps. It is a marvelous specimen of mechanical contrivance for crushing the ore. Many parts of the machinery work automatically. I ascended the various floors, and had all the processes minutely and clearly described to me in a most courteous manner, by the superintendent of the battery. I afterwards went down into the mine, first to the 70-feet, and then again to the 150-feet levels. In this way, I passed two hours wandering underground with a candle in my hand, and inspecting the gold-bearing lodes of one of the richest mines in the Randt. This mine possesses magnificent lodes, and millions of tons of gold-producing quartz. There is a prospect of most profitable results in it for years to come. Altogether, from what I have seen of the various gold mines of Johannesburg, I am satisfied of the permanence of its gold fields. Of course they are not all of equal value; but many, even of the poorer mines, when they come to be worked more scientifically, and on proper business principles, will ultimately be found to pay fairly, although they may never be destined to yield such brilliant results, as some of those I have mentioned. The Market Square is the largest in South Africa, covering an area of 1,300 feet in length, and 300 feet in width. Some idea of the growth of Johannesburg may be gathered from the fact, that at the latter part of the year 1886 there was not a Post Office in existence, whilst the revenue of that department for the first quarter of 1887 was £167, and at the end of 1888 it had risen to £7,588.

Johannesburg's Market Square in 1889

This extraordinary and rapid growth has unfortunately produced the usual results, when an immense population is suddenly planted on a limited area, without any proper sanitary arrangements being provided for their protection. From its elevated situation and naturally pure and dry atmosphere, Johannesburg ought to be a very healthy town. That it notoriously is not so, and that the amount of sickness and death-rate from fever and other diseases is abnormal, must, undoubtedly, be attributed to the great neglect and utter absence of an efficient system of drainage. I fear this state of things will continue; and the certainty of serious increase, as the population continues to grow rapidly, is only too likely, until there is established some kind of municipal body, acting under Governmental authority, to adopt a thorough and complete system of sanitation. It is to be hoped that the Transvaal Government, which is having its treasury so rapidly filled from the pockets of the British population, which is pouring into Johannesburg, as well as into so many other towns in the Transvaal, will awake in time to the importance of taking measures for thoroughly remedying this great and glaring evil, which is becoming such a scandal, as well as creating such widely spread and justifiable alarm among the British community in the Transvaal.

I love this narrative as it captures the immediacy and excitement of Johannesburg as a mining camp and a permanent city in the making, driven by gold. I am able to reproduce this account because the Gutenberg project of digitizing texts gives us the entire book free online (e-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Taavi Kalju and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team). The Gutenberg project turns Young into a classic of colonial literature and makes it accessible to all (click here to view website).

The book is there for you to enjoy complete with the superb sepia toned photographs (pasted in as authentic photographs into the original pages of the book). The original includes a map of Southern Africa in 1889 (pasted in at the rear) showing the routes followed by Young and his party. Today, I am sure many copies have been stripped just to retrieve this now 'antique' map. A particular visual delight are the small floral motif decorations at the start and end of each chapter in an arts and crafts style of book production.

Small floral motif decorations

It took another twenty years and a catastrophic war before the Union of South Africa was achieved. Young's vision of an imperial federation caught something of that possibility as early as 1889 and the idea of confederation was one long in gestation in the minds of many such as Sir George Grey and the 4th Earl of Carnarvon. But their ideas and approach were discredited because the rights of the local people, black and white, were sidelined. The route had to be through self determination, national identities, local democracy and self government. Instead, at that time, as in today's world, bellicosity and the voices for war carried the day simply because the plans for unification were imperial and far too British. It took a long time for the realization to dawn that unity and political frameworks have to be home grown and that national identity has to be shaped from within a country. The ultimate imperial successor was the Commonwealth which always seemed to me to be an anachronism and a throwback to just what Young had in mind. Nonetheless, his ideas about the practical benefits of railways, drainage, effective civic administration, the building of city halls (the Durban Town Hall is much admired by Young) and installing adequate sanitation were what mattered in raising living standards.

Durban Town Hall

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.