Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, well-known journalist and Joburg enthusiast, Lucille Davie, explores the layered history of Somerset House. The piece was first published on the City of Joburg's website on 7 November 2003. Be sure to read all the way to the end where Davie provides an inspiring 2017 update. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

It must be the dustiest, mustiest bank basement in town. It's in the former United Building Society's 97-year-old building on Gandhi Square, now known as Somerset House. The basement has got an eery, stopped-on-a-day feeling about it.

I recently went down into the basement and felt as if I was entering Johannesburg's version of an ancient Egyptian tomb - it was mouldy, very dusty, very musty and it looked like the bank officials had finished up work on a day, locked up and left the city, although it was operational up until three years ago.

It's actually the safety deposit box vault of the United, now Absa Bank, secure behind a 25cm thick double steel vault door. There are around 1 000 boxes behind those doors and another set of vault doors, from floor to ceiling, most of them firmly shut, with their keys lost years ago. Some boxes have their doors open, revealing empty insides.

Entering Johannesburg's version of an ancient Egyptian tomb (Lucille Davie)

Coming down the stairs into the room, the walls are mouldy, with peeling and bubbled paint. At the bottom sits the large table and chairs at which box owners examined the boxes and their contents, before putting them back into the vault.

The room still retains its beautiful decorated green tiles half way up the walls, and its small green and white floor tiles. It has a high ceiling, and on one side, the glass doors of the manager's office.

Architect Mark Hindson, while doing research on Edwardian buildings in the city in 1982, recalls coming across old plans in the vault basement, which, when they were handled, simply turned to dust.

The present owner of the building, who wishes to remain anonymous, says about the boxes: "All those people who used to have boxes have melted away." He says the owners of the boxes died years ago, and with their deaths, the keys disappeared.

The owner is the son of a former inner city property dealer, who used to buy buildings around town when he arrived in Johannesburg in the early 1900s. These days, the owner of Somerset House, together with his brothers, still owns scattered buildings around the city.

He says people used to approach his father, offering him buildings, and he used to buy a building if he thought it was "a snip".

"When people found out, they would run to see if they could cancel the purchase, because surely if he [the father] was buying it, it must have been too cheap," he says, with a smile.

Somerset House is one of many old inner city buildings which is looking a little neglected. Many buildings in this condition have simply been bricked up to prevent squatters from moving in and doing more damage. But, unlike these buildings, Somerset House is still functioning, and has tenants.

Somerset House looking tired (before its 2017 restoration)

Former grandness

Some of its former grandness is still visible. Its arched entrance is in Fox Street, consisting of three storeys in attractive, grey-plastered Edwardian/classicism style. Walking into the entrance, you'll be greeted by glossy green, period wall tiles and classic black and white marble and slate floor tiles.

Fox Street Entrance (following restoration in 2017)

Historic wall and floor tiles (The Heritage Portal)

The entrance gives way to an interior court that stretches up the three storeys, an uplifting space, allowing light into the building. The ground floor retains its metal lift, no longer working, surrounded by a staircase. Each floor has wrought iron and wood-topped railings. The roof used to be covered in Georgian wired glass, with glass windows, fitted with brass, on the three sides. These days it's covered in transparent plastic and metal sheeting. It must have been glorious in its day.

Inside Somerset House (The Heritage Portal)

Spectacular roof structure (The Heritage Portal)

The exterior has also been changed. The upper floor had balconies and French doors. The first floor had large windows. The balconies and doors have disappeared and been replaced with slightly recessed, wider windows.

The United Building Society

In fact the bank closed its doors in 1930, although the basement remained in place until 2000. The United Building Society was established in 1889.

According to John Shorten in Johannesburg Saga, it had inauspicious beginnings: "Johannesburg was only three years old when a small group of working men met in the office of the Special Landdrost, Captain Carl von Brandis, to start a modest building society. They had no idea of doing anything beyond helping one another to raise money over a short term for the building of decent though unambitious houses, but from the few sovereigns clinked on the table that day there has grown the United Building Society - the largest institution of its kind in South Africa and one of the biggest in the world."

It rented its first office at no 6 Victoria Buildings, part of the old Jeppe Arcade in Commissioner Street.

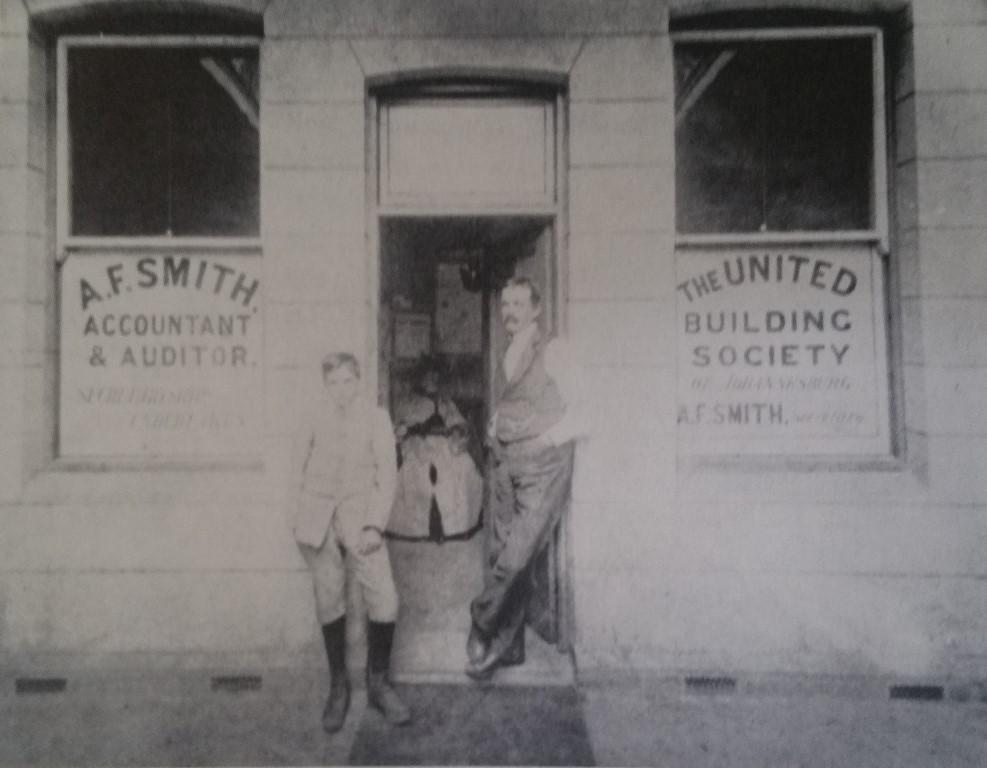

First Office (Johannesburg Saga)

Office clerk Arthur Kyle recalled the simplicity of that first office: "There was not even a counter, only a standing desk with one small table in the corner for the office boy. AF Smith, the secretary, sat at the desk. There were no typewriters or printed forms, but we had a telephone."

Most of those early clients were miners and artisans, taking out housing loans of £150.

In 1899 the United could boast assets of £50 000. In the same year the Anglo Boer War broke out, and the United closed its doors for nearly two-and-a-half years, waiving all interest on bonds that had accrued during the war.

In 1897 an Australian, Frank Blackwell, was appointed secretary. After the war he instituted a number of innovative rules, says Shorten. He put in place a strict system of building inspection; anti-fraud regulations; arranged the office hours to suit Friday and month end days to accommodate customers' demands; and recommended an emblem for the United.

Shorten explains: "This is the classical figure from the fables - a strong man, kneeling on one knee while trying to break a bundle of sticks against the other - the sticks symbolising strength through unity."

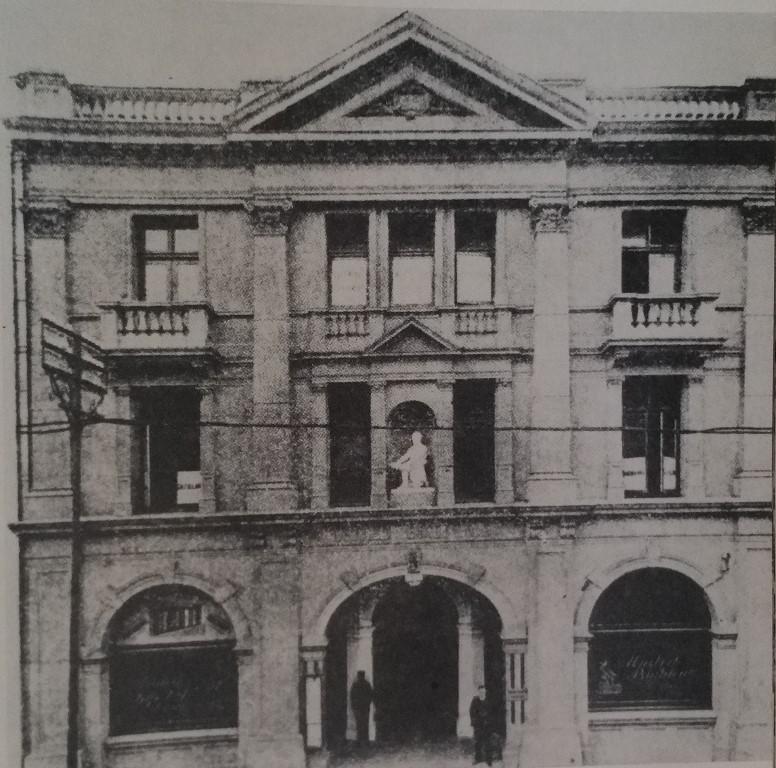

The figure was modelled in marble in Italy, and by the time it was ready, so was the new three-storey United office building. The marble figure was placed on a pedestal in a recessed arch on the first floor exterior of the new building. The emblem was reproduced on bank books of clients and the United's house tie.

The new office building was constructed in 1906. The building society took up the ground floor and the basement, which housed the United Safe Deposit Company, the dusty, musty space of today. On the first floor Baumann Gilfillan, a group of lawyers, had their rooms and on the second floor, an accountant, AEA Williamson, rented space.

Shorten says that the directors issued a circular to members, announcing that the offices had been "superbly fitted and replete with all conveniences which experience has taught are necessary to the comfort of the public and of the officials".

After the war the United continued to grow, and with interest rates fixed across the board at 12 percent, it expanded business. By 1907 it was expanding outside of Johannesburg, and receiving deposits through an arrangement with the National Bank of South Africa Ltd. In 1908 a travelling representative was appointed to visit country towns.

Old photo of the 1906 office later renamed Somerset House (Johannesburg Saga)

United's assets

By 1909 the United's assets stood at £312 000, an increase of 500 percent over the past decade. Despite this, the operation was still very modest: less than 12 staff members, all male, with the average loan being granted at between £500 to £1 000, sufficient for building a four to five-roomed middle-class home.

In 1910 the United Building Society set a precedent that was soon followed by other building societies. Previously home applicants had to buy shares when applying for a loan. It changed this rule, issuing loans without any pre-conditions. This encouraged working class people to apply for bonds, leading to the development of some of the city's southern suburbs. This established the building society as the working man's bank.

"Rough-looking miners and artisans would visit its offices on a Saturday morning to deposit their cash or apply for building loans," according to Shorten.

In 1919 the United's assets stood at £912 000, a 209 percent increase since 1909. It spread its influence: a branch in Cape Town opened in 1923; a branch in Port Elizabeth in 1926; one in Durban 1931, East London in 1938 and Bloemfontein in 1939. It was now represented in all four provinces - Orange Free State, Transvaal, Cape and Natal.

But it soon needed more space in Johannesburg. A new building, on the corner of Joubert and Fox streets, was built in 1928, called United Buildings. The marble figure was erected in the entrance to the building.

In the 1930s United again set a precedent. By reducing its fixed deposit and savings rates, it was able to reduce its lending rate from eight and a half percent to six percent.

Shorten comments: "Applications for building loans broke all records and within a few years the United, having meanwhile been eclipsed in size by two other building societies, again became the biggest institution of its kind in the country, a lead it has maintained to our day."

In 1970 the United had around 174 000 shareholders and 639 000 depositors, with mortgage bonds totalling R542-million and assets of R680-million.

But by the 1990s times had changed and building societies became obsolete. In 1991 Absa Bank was formed, an amalgamation of a number of building societies: Allied Bank (Allied Building Society, established in 1888), Volkskas Group (Volkskas Co-operative Limited, established in 1934) and United Bank (United Building Society, established in 1889).

Absa still occupies the building on Joubert and Fox streets, on Gandhi Square, taken over from the United Bank.

ABSA Building Gandhi Square (The Heritage Portal)

Somerset House

When the building was sold to the owner's father in 1930, it changed its name to Somerset House. And the building took on a commercial role, according to Hindson. The "large front arched windows were taken away and replaced by shop fronts". The banking hall became the auction room, called Don's Mart, where second-hand furniture was sold.

Inside the courtyard a barber shop was "created for someone who had lost his job with his employer of many years, because he took off a religious holiday", says the owner. The shop was called Bennie the Barber. The owner says he remembers the barber well, all his haircuts were done at Bennie's.

Next to Bennie the Barber, on Fox Street, was Rolly's Snack Bar, at which, the owner says, you could view and select your meal, and a lever was turned and your meal was delivered by the machine - the city's first take-away vending food machine.

According to Hindson, in 1932 a public passage or arcade was created, running from Fox Street through to New South Street, on Gandhi Square. There used to be a small restaurant backing on to the square, called the Traffic Square Restaurant. The arcade became an important passageway between Fox Street and the square.

The arcade re-emerged during restoration work in 2017 (The Heritage Portal)

In 1935 a metal lift was installed, cutting into the staircase, which was subsequently reduced in width. The owner says that in the 1960s he stopped the lift, mainly because it had to convert from DC power to AC and that was a costly business.

It seems that in the 1930s the two upper floors were converted into seven residential flats, in a city that had a mixed residential/business feel. But by the early 1950s this again changed as people abandoned the city for the suburbs, and the space again was rented by small businesses.

High Court Building

The neighbouring five-storey High Court Building, believed to be older than Somerset House, and owned by the same company, housed a number of lawyers, and was, over the next few years, vacated by them. These days it houses a bottle store and a hairdressing salon on its ground floor, and seamstresses and tailors on its upper floors. Millew's Fashions occupies its Fox Street corner, at one time a very fashionable place to visit, owned by someone who left Europe shortly after World War II.

The owner of Millew's used to visit the US to ascertain the latest fashions. He walked into a designer's warehouse one day in New York and asked if he could order a dozen each of a range of different styles. The salesman turned to his backroom supervisor and shouted: "I've got someone here who wants some remnants," referring to a small order when most orders placed were for hundreds of items.

The owner describes him as having been "a wonderful gentleman" who attracted an enormous clientele. Nowadays Millew's is a bare-walled shop with stacks of metal clothing racks, selling second-hand clothing.

High Court Building with Millews signs (The Heritage Portal)

Top of the High Court Building (The Heritage Portal)

Traffic Square Restaurant

In 1950 Phoebus Georgios took over the restaurant, and 43 years later, he's still running it. It's called the Traffic Square Restaurant. He says it got its name from its previous owner, a traffic policeman, and he never saw a need to change the name. Before this, from 1946, it used to be Perk's Pies, with a small kitchen.

Georgios says he used to run a restaurant called the Guildhall Tearoom for eight years, in Market Street, next to the Guildhall Pub, one of Joburg's oldest pubs.

Looking up Harrison Street towards the Guildhall (The Heritage Portal)

When Georgios took over the restaurant in 1950 it was a small, horseshoe-shaped place. He remembers the square as a car park, shortly after the Johannesburg Law Courts were demolished in 1948 and before it became a bus terminus called Van der Byl Square. Gandhi, who left the city in 1914, used to practise as an attorney at the courts, which were the city's first law courts, in what was known as Government Square, now Gandhi Square. The courts were in use until 1911 when the Pritchard Street Supreme Court building was built and court cases moved there.

Georgios remembers that trams used to ride the streets of the inner city.

In 1972 Georgios asked his landlord, the present owner, whether he could expand the restaurant's space by enclosing the arcade. This was done and the kitchen size was increased, and the present counter was created where the arcade had been.

The Traffic Square Restaurant hasn't changed much since those days. Its customers come in before work for breakfast and coffee, and they've got a wide selection to choose from: sardines or baked beans or spaghetti on toast, or mixed grill, perhaps with monkey gland steak, or mince, mash and salads, among other items on the menu.

Georgios says he knows most of his customers by name - they work in the vicinity. At 73, he has no intention of retiring - "I would die if I retired" - and he'll probably still be living in the house in Robertsham where he's been for 45 years, when he dies.

Somerset House now

Somerset House these days is a sad-looking building, a shadow of what it could be. In 1975 a 15-storey office block was erected next to it, on Rissik Street. During excavation for its foundations, Somerset House was not supported, and it developed serious cracks along its western wall.

During construction, bricks and other building debris landed on Somerset House's glass roof, causing extensive damage and allowing rain into the building. The owner replaced the remaining glass with plastic and metal, which still protects its beautiful inner courtyard from the weather.

The building is occupied by workers from the Traffic Square Restaurant, and other workers working for the owner.

And, in the meantime, that basement remains dusty and musty.

Metropolitan Building next to Somerset House (The Heritage Portal)

Update: 13 December 2017

Successful inner city property developer, Gerald Olitzki, bought Somerset House and the neighbouring High Court Building in 2016. Both have been undergoing restoration over the past year, and Somerset House is set to regain its former grandeur with its glorious tiles and marble floors, restored balconies and large window frontages.

Whereas a good deal of property developers are often looked upon as uncaring of the heritage value of properties in their drive to make a profit, Olitzki bucks that trend. He has been buying, renovating and converting inner city buildings into office space for the past 29 years, and has turned the area around Gandhi Square into a vibrant work and play oasis. He was the developer who originally proposed revitalising Gandhi Square back in the 1990s, then paid for the revamp. Today it is a vibey people place, as well as a bus terminus, lined with restaurants and coffee shops along its southern edge, and banks, offices and retail spaces on its northern edge.

But Olitzki is more than this - he is a passionate urban champion who genuinely wants to revive his 'hood. He now owns several dozen buildings in the inner city that he was reinvented as office space. He has found that he is now renting that space to companies from whom he originally bought the buildings, and reports that his buildings are "substantially full".

He has had his eye on Somerset House since the 1970s, so when is came up for auction, he jumped at the opportunity.

"The acquisition is more a fun and passionate exercise than a commercial exercise," he says. "It really needed attention, the old arcade is almost an operatic gallery."

Olitzki knew the previous owners, the Amoils brothers, who used to own a large number of buildings in the inner city. They finally sold their last 12 buildings, including Somerset House and the High Court Building, last year.

Olitzki hasn't fully worked out what he will do with the spaces fronting Somerset House's "operatic gallery", but I have no doubt the building will capture not only a glimpse of what Joburg's former glorious arcades looked like, but it will be an inviting space to enjoy a small slice of the Joburg of times past.

High Court Building and Somerset House after restoration (The Heritage Portal)

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.