Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

This must be a first in the Johannesburg blue plaque collection... a bus shelter has received a heritage marker. I last wrote about the condition of the bus shelter in 2014 when it had been left derelict and was in a sad state of neglect. There has been a complete turnaround with the bus shelter now restored and celebrated as a unique item of Johannesburg heritage. This is a bus stop with a difference.

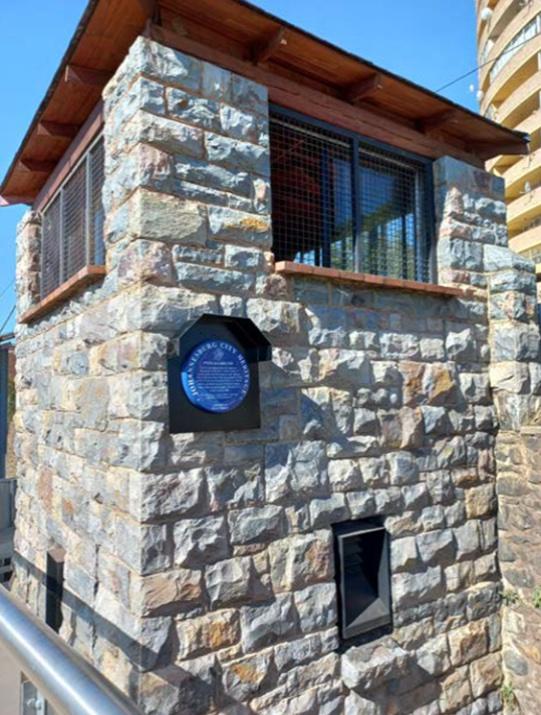

The restored bus station (Eric Itzkin)

I am delighted to share the news that the City of Johannesburg has unveiled a new blue plaque for a bus shelter which is located at the corner of Tudhope Avenue and Louis Botha Avenue. The inscription reads:

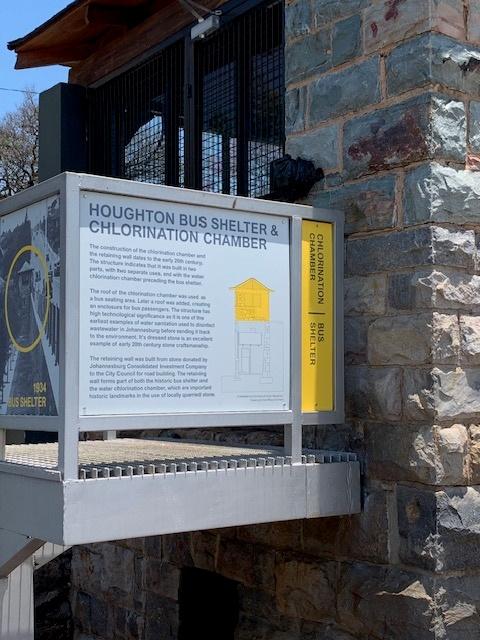

Built by the Johannesburg City Engineers Department in 1934, this is a rare example of quality granite mine stone masonry and craftsmanship evident in so many of the City’s projects of that period. The bus stop served the trolley buses that ran along Louis Botha Avenue to Norwood, Orange Grove, Bellevue and Sydenham. The trolley bus system closed in 1986. The chlorination chamber below is the earliest known water purification chamber in Johannesburg.

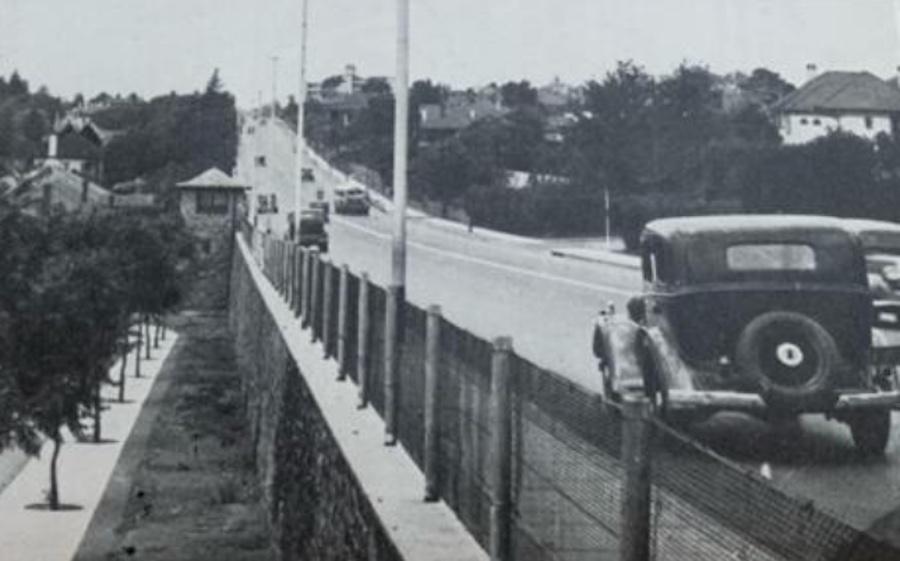

Looking towards the bus station (Eric Itzkin)

The bus shelter is a remarkable structure. As the inscription mentions, it was built by the Johannesburg City Engineers Department in 1934 and is a rare example of city construction of the period. It was made of discarded granite mine stone and the stonework is exceptional. With windows on three sides and the open entrance on the Louis Botha Avenue side, it was a practical contribution for people catching the city municipal trolley buses that ran along Louis Botha Avenue.

A few generations ago, cars were, of course, less common and Louis Botha Avenue was a much narrower thoroughfare (although the bus shelter was part of a project to widen this main road in the mid 1930s). Through the decades there were several attempts to widen the road, cutting pavement width to create an additional traffic lane and ease the flow of traffic. Widening the road often came at the expense of the trees and the fact that an avenue means a tree-lined street was quickly forgotten.

Old photograph of the bus station

Before the motorway system and new highways of the 1950s and 60s, traffic jams at peak hour were not unknown. Robots and right turns slowed things down. The first motorway or freeway was the Harrow Road development with the underpass at Louis Botha, heading towards St Johns College and swinging towards Houghton Drive on St Andrews Road.

In the very early days of the city, Louis Botha Avenue was called the Old Pretoria Road and was a primary access road to Johannesburg. It was first a wagon route from Pretoria. During the South African War (Anglo Boer War), a defensive block house was erected at the point of steep descent into Orange Gove. When Alexandra was created, this was the primary transport route for Alex residents and for the northeastern suburbs of Highlands North, Sydenham and Orange Grove.

The interior of the bus shelter had a sturdy wooden red painted bench running along three sides. The bus shelter offered a fine service to school kids and others who travelled by bus. The taxis were Rose’s taxis and certainly not used by school boys and girls.

At the base of the shelter, which could only be accessed from the Houghton Drive side, was an early water chlorination plant. We believe this was one of the earliest efforts to purify water in Johannesburg.

I remember the bus shelter as I waited for my bus here and took shelter from the sun and rain. It looks like a miniature dolls house. Between 1957 and 1962 I attended Barnato Park School, first for six months at the primary school and then on to the high school (the prestigious Johannesburg Girls High school). Our family home was in Highlands North. As my mother never learnt to drive a car, the trolley bus service was the way to travel to and from school along Louis Botha Avenue. I walked from the school which was (and still is) in Berea at the end of Fife Ave. Beyond lay Hillbrow.

My choice of trolley buses was a 14 or a 13 heading either to Highlands North (number 13) or to Sydenham (number 14). There was also a number 10 bus that turned off at Gallagher’s corner and headed to Norwood down 9th avenue and past the Patterson Park Bowling Club and the Municipal pool. If I chose the Highlands North Bus, I disembarked at the Dolls House and walked home along Boundary Road. If I chose the Sydenham bus, it was usually a walk from the Sydenham bus terminus on Durham Street or, for variety, I would get off at the Carisbrook Street stop and walk home along Viljoen street. Slowly but surely, I built my knowledge of the geography of the city.

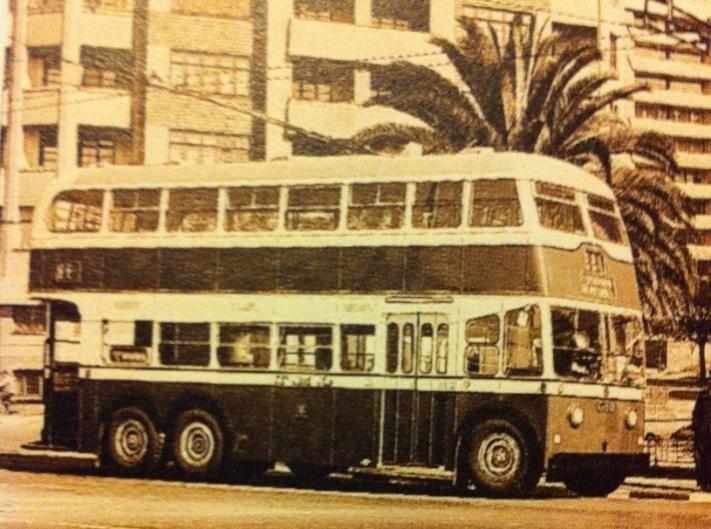

A Johannesburg trolley bus

Tony Spit in Johannesburg Tramways comments that the electrically powered trolley bus was far superior to the diesel buses because of the altitude of Johannesburg being over 6000 feet above sea level. Spit sums up the Louis Botha Avenue route: ’For almost three miles the trolley buses must stop only infrequently and can travel at high speeds in the fast lane of Louis Botha Avenue'. I think the high speeds bit was an exaggeration, particularly when one was aware that there was a sharp downward descent from Bellevue and the King Edward VII stop down the hill to the curve in the road as the route entered Orange Grove. The steep descent was treacherous and was known as 'death bend'. Many a young blood racing down in a fast new sports car or a speedier motor bike ended their lives at that point and one sighed at the waste of life. Later rumble strips, a change in the camber of the road and crash barriers improved the survival statistics.

The buses stood out because they were painted red and white with a distinctive number in gold on the front as a permanent feature and a pane above with a wind-up mechanism to show the route number and destination. The side panels of the bus carried adverts. The buses were double decker, and it was always fun to grab a top front wide angle view seat on the top deck. The buses ran on electric power with the power coming from a system of overhead cables with a long pole transmitting the power to the engine of the bus. It was a curious system as sometimes the electrical pole detached from the cable above and the bus came to a halt. The driver had to disembark from his front cab, haul a long rod stored under the bus, and use this like a fishing rod to grab the power pole and reattach it to the cable network. It was a point of excitement and exasperation when this happened, but the passengers were very tolerant. The trolley buses were well designed with a rear entrance and the back stair leading from the platform to the top deck and a front exit door. We mainly hopped on and off at the back of the bus. Trams still ran when I was a child, but the tram route ran through Yeoville and stopped at Bedford Road; hence the bus shelter was purely for the trolley buses and belongs to that era.

Red and white trolley bus (Sourced by Steve Hayes)

I have fond memories of Johannesburg’s bus service. I travelled wherever I wished to go by bus from a young age. I had to be an independent child. From the age of 11 I caught the buses of the city. In the week I went to school and on the weekends I travelled by bus to Yeoville or Berea for play dates with school friends or went with a girl friend to the down town cinemas - the bioscopes of Commissioner Street. A favourite trip was a Saturday morning visit to the Orange Grove library. As a teenager I explored the city bookshops such as Vanguards and Jutas.

I think my relationship with the Johannesburg City bus network was both loved and loathed. I envied people who drove cars. I loved the sense of community and conversations on the buses with complete strangers or with fellow school mates. I counted the lost minutes of time wasted waiting at bus stops for a bus to arrive or not arrive. I nurtured the ambition to get a license and ultimately buy a car to free me from the tyranny of wasted time and the long walks at either end of the bus journey. But I was also grateful to Johannesburg Municpal Transport (JMT) for giving me mobility.

The buses were manned by two fellows: a conductor who collected the cash in a coin counter device and a driver who sat in a front cab. He was the important man on whom we all depended. Passengers could not talk to the driver. I remember I had a book of season tickets – these bus coupons were bought at a kiosk at the City Hall on Market Street and offered a discount. Fares were calculated in stages. Adults paid 5 cents for 1 to 2 stages but 3 to 5 stages were charged at 8 cents with a half cent discount for a coupon. Children under the age of 12 travelled for exactly 3 cents and toddlers and babies travelled free.

In those days Louis Botha Avenue had many more trees and there was even a municipal fountain at Bedford Road. It was an apartheid world and I do remember puzzling away at the conundrum of why black people were expected to catch buses with green “Nie Blankes / Non- White” signs at the front and white people were better served with a more frequent city to suburb service. However, sometimes one could wait for half an hour for a bus and I always kept a book handy to read. I was always nervous about becoming so engrossed in the story that I would miss the bus trundling down from the fire station at the start of Louis Botha. The alternative for black people was the Putco green bus service and as I child I also pondered on why I could not catch a much more cheerful single decker black people only bus.

Today, the bus shelter is no longer used to service bus passengers. It has lived beyond its original purpose and is barricaded by armour crash barrier steel. Its history is honoured and the story is told through the efforts of Tsica Heritage and Eric Itzkin. It has become a feature and a small reminder of history.

An interpretation panel has been added to the bs shelter (Kathy Munro)

The Reya Vaya is a public transport system for city commuters from north to south. The system is meant to service an area spanning 330 Kilometres and the vision is to allow more than 80% of Johannesburg’s residents to catch a bus. It is a capital project of enormous expense, futuristic in its conception and road revisioning; steel and concrete barriers regiment the new buses. The town planners see the system as Transport Oriented Development with densification of dwellings in the suburbs following. Unfortunately for Louis Botha Avenue, it has been a slow delivery process. Conflict with the powerful taxi owners association who ply the route to Alex, has meant that there has been no delivery in years. I have yet to see a Reya Vaya bus run down this corridor. At the moment we appear to be in a no man’s land – a space between concept, change, and construction. The potential passenger of the new system is still a pedestrian or drives a car or hails a mini bus quantum taxi or calls an Uber.

To celebrate the positive, the old stone bus shelter has been saved. It has been awarded a blue plaque and there are some impressive history boards. For me it is a reminder of how much Johannesburg has changed. The familiar daily routines of waiting at a bus shelter and catching a bus has passed into history.

Main image: A zoomed out photograph of the bus shelter with space for the water chlorination plant below. The building in the background is Imbali, a predecessor in concept to Ponte. It was built in the 1960s with spectacular views towards the Wilds, Houghton and beyond to the north. (Kathy Munro)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.