Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

"For young black South Africans like myself," Nelson Mandela wrote in his autobiography, "it was Oxford and Cambridge, Harvard and Yale all rolled into one." Of the hundreds of pages in Long Walk To Freedom, barely a dozen recount Mandela's days at Fort Hare University. Understandably so. He spent less than two years of his 94 years as a student there.

He left Fort Hare University halfway through his studies due to a student strike over living conditions, most notably food rationing. “At that moment, I saw Dr. Kerr less as a benefactor than as a not-altogether-benign dictator", he said.

His mixed emotions were not his alone. The entire enterprise of mission schools stood at an ambiguous, and conflicted crossroads. It was partisan to the colonial project, but yet educated students who were opposed to colonialism. It shied away from political involvement, and yet sanctioned the ideals of equality through its religious teachings.

Fort Hare

in a lecture titled Colonial Education and Missionary Evangelism given at UCT and published in the book Blytheswood: A unique South African mission station, Professor Marlene Caitlin states: "There are two points about viewpoints about missionaries in Southern Africa. Some think of them as agents of conquest, tools of imperialism, tools of a capitalist system, who fastened the yoke on a subject people and sapped their will to resist. Others see them as true servants of God, benefactors who brought the good news of the gospel to those who had not yet heard the Word. Benefactors who, in seeking to spread the Word, created literacy, schools and hospitals."

African customs and social order were intact for a long time owing to the power of the chiefs. Michael Ashley, in an essay titled African Education and Society in the 19th Century Eastern Cape, describes how "African reactions to modernization, and the education which accompanied it, changed from an initial rejection to a growing acceptance and enthusiasm. Rejection sprang from their realization of the threat European education posed on their traditions and identity. Acceptance developed with the breakdown of intact traditional societies and the realization that education was the road to mobility, to the achievement of aspirations in the new society that they were entering."

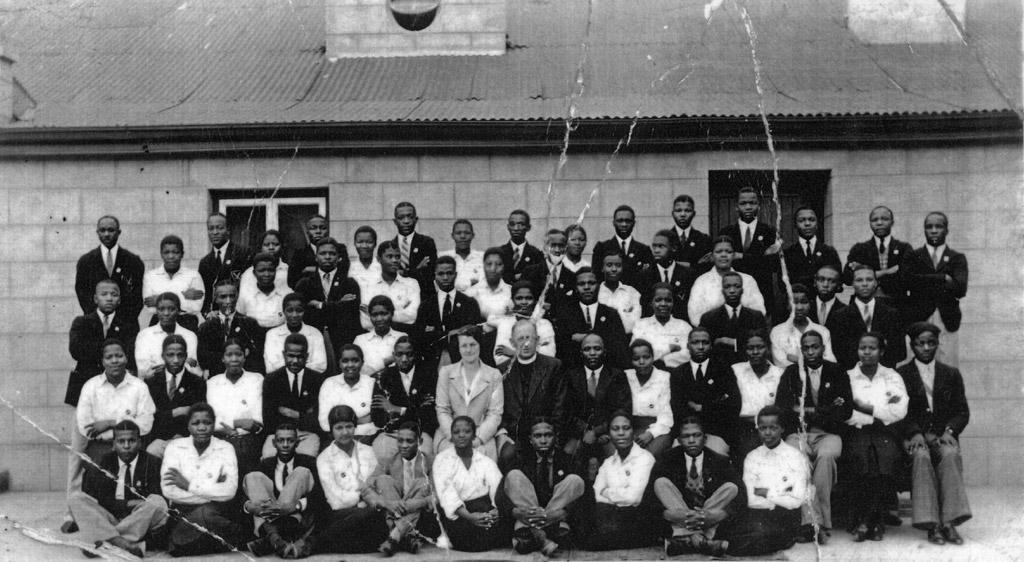

In the totality of time, mission education has come to earn a more positive re-evaluation. Mandela himself did ultimately receive his bachelor's degree from Fort Hare University through long-distance study. Given their flaws - elitism, condescension, timidity - mission institutions such as Fort Hare produced an illustrious list of leaders in South Africa's freedom struggle and society. Prior to Fort Hare, Nelson Mandela, for instance, had been a student at two iconic Eastern Cape mission schools – the non-denominational, London Mission Society (LMS) founded Clarkebury School and the Methodist Healdtown Institute.

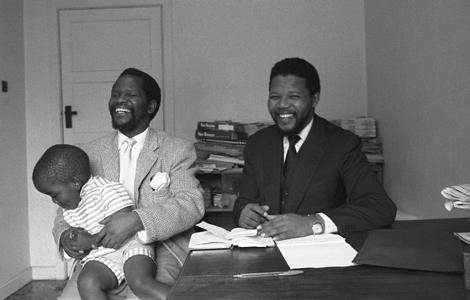

Mandela and Tambo

There he had occupied classrooms which had or were soon to be occupied by the likes of Govan Mbeki and Raymond Mhlaba, his fellow Rivonia Treason Trialists. Robert Sobukwe, Alfred Nzo, Victoria Mxenge, Richard Msimang, Smuts Ngonyama, Justice Thembile Skweyiya, Elijah Barayi, Matthew Goniwe and John Nyathi Pokela are amongst a long list of politicians who followed in the threesome's footsteps to be amongst Healdtown Institute's illustrious alumni.

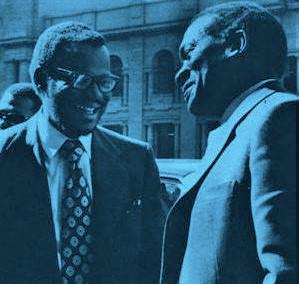

Robert Sobukwe (with Chief Buthelezi)

Victoria Mxenge

The Reverend Seth Mokitimi, housemaster and chaplain at Healdtown Institute (he later became the first black president of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa) observed in 1948: "Practically all the outstanding African personalities who have become leaders of their people owe the best in their lives to missionary influence and education."

A less publicly known fact is that a number of South African mission schools served as fountains of learning for many Southern African pro-independence leaders. Botswana's first and second president Sir Seretse Khama and Dr Quett Masire, Ntsu Mokhehle (Lesotho), Robert Mugabe (Zimbabwe), Julius Nyerere (Tanzania) and Dr Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique) were all students of various mission schools at primary and high school levels in South Africa.

The intentions of missionary education were both deliberate and not. Their founders clearly deviated away from the colonial intention of total subjugation of indigenous groups by espousing their educability. Their beliefs, however, were a long way from liberation theology.

"Under colonialism, there's a tension between the mission and the colonial authorities," said Nigerian Dr Olufemi Taiwo, author of the 2014 book How Colonialism Preempted Modernity in Africa. There was a missionary idea that black people could be modern. And most churches cannot pronounce that people are less human. So you may have a patronizing attitude. But if you think that Africans cannot benefit from education, why build schools?"

In all its forms, mission education was virtually the only form of education available to black South Africans during the colonial era. The first mission schools, Lovedale and Healdtown amongst these, were founded in the mid-1800s, shy of a century before the government started building its own schools for black students. Just as conspicuous, in the 1930s far more black students (15 000 to 18 000) were going through mission education than were at newly-built government schools.

"For the ideals that many would carry into the political arena, mission schools put black students into a multi-racial environment", said Richard Elphick, a historian at the Wesleyan University, USA, and author of the book "The Equality of Believers", Protestant Missionaries and the Racial Politics of South Africa. "Mission schools had amongst their admissions children of the white teachers, missionaries and colonial authorities. In its heyday, a major mission school such as the Scottish Presbyterian Lovedale Mission boasted of over one thousand students drawn from a multitude of Southern Africa's tribes, and speaking a variety of languages."

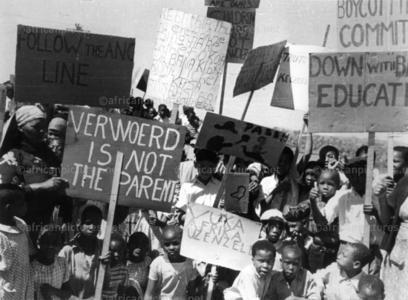

For all these reasons - academic, religious and cultural - mission schools were an impediment in the eyes of Afrikaner nationalists. In the ensuing years after 1948, the year it came to power, the National Party exerted state control over mission education, erratically imposing its apartheid policy, and advocating for only "non-European" languages to be the mediums of instruction (a complete about-face would happen two decades later in 1976). A great number of mission schools buckled under the pressure and capitulated. Many were subsumed into the homeland education system. Faced with a future in direct contrast to their ideals and Christian ethos, many chose to voluntarily shut down.

Protest against Bantu Education

Like so much, this changed after Nelson Mandela's release from prison in February 1990. Some of the schools which had chosen closure were re-instituted by church organizations, and some by the impassioned efforts of their alumni.

In 2008 the then president Thabo Mbeki, together with the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Njongonkulu Ndungane, put into motion a plan that would see to the restoration of South Africa's mission school heritage. The Historic Schools Restoration Project (HSRP) aims to revitalize the rich heritage of South Africa's historic mission schools and to transform them into sustainable and aspirational African institutions of educational and cultural excellence.

Mission education lies at the nexus of South African history and society. It represents much that has shaped and influenced the turn of events, politically and otherwise into the present. If the schools' buildings cannot be resurrected, then the schools' heritage as foundations of education should at the least, be commemorated.

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg.

After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue.

On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa.

Visit www.gatewaystoanewworld.wordpress.com to see more of his work.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.