Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Peter Ball continues his epic History of Southern African Railways series with this superb piece on the line from Mossel Bay to Oudsthoorn. He sets the historical context, highlights the incredibly difficult terrain for railway building and concludes that it is remarkable that the line was built at all.

The Outeniqua Mountains run parallel to the coast in the region we now call the Garden Route, they separate the coastal strip from the valley of the Olifants River, which is better known as the Klein Karroo. The mountains were a natural barrier to those who wished to venture inland beyond the coastal shelf and the native people of the Cape, the Khoikhoi, were the first to discover ways over them, by following animal tracks.

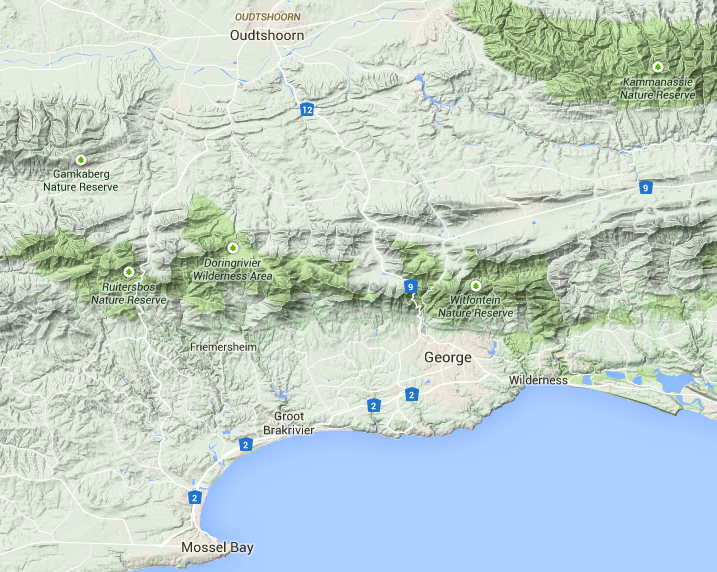

Terrain Map (Google Maps)

When the Dutch East India Company (or VOC) established a victualing station at Cape Town (in 1652) for its ships sailing to and from the Spice Islands it never intended to colonise the region, however it did send out expeditions for the purpose of trade with the Khoikhoi. One such expedition took place in 1689 and was led by Ensign Isaq Schrijver who was sent eastwards over the Hottentot-Holland Mountains, along a track which would become the old Cape Wagon Road.

His journey took him and his column of men through the Overberg and further onto a shimmering bay having a backdrop of mountains. This sheltered bay was well known to the Portuguese sailors as an anchorage and they called it “Aguada de Sao Bras”- Bay of St. Blaize - and it was where Bartolomeu Dias first set foot in 1488 after he had rounded the Cape, with his tiny fleet of three caravels. The bay where he landed is known today as Mossel Bay.

To the east of the bay Schrijver found the terrain to be impassable owing to deep ravines and dense forests and he was thus forced to strike northward to find a pass over the Outeniqua Mountains, which he duly did when he found an old elephant path that eventually emerged onto the stony plains of the Klein Karroo. This was the first pass over the mountains known to Europeans and was named the Attaquas Kloof Pass, after the local head of the Khoikhoi. The pass still exists in part and is situated slightly to the west of Thomas Bain’s Robinson Pass (of 1869) and it can still be followed on foot or by driving a 4X4 vehicle - on receipt of a special permit issued at Bonniedale farmhouse.

In the mid 19th century communications between the coastal strip and the Klein Karroo were greatly improved when a new road pass was opened in 1847, between George (founded in 1811 and so named after King George III) and the village of Herold by the Colonial Secretary for the Cape of Good Hope, John Montagu. The pass was duly named in his honour and it replaced a very steep and dangerous pass known as the Craddock Kloof Pass of 1812 (which had been used by the Voortrekkers). The Montagu Pass was engineered by Henry Fancourt White and he was able to reduce the gradient by spending more time winding around the lower slopes of Craddock’s Peak and finding a crossing of the watershed at a lower elevation. The road although untarred and narrow is still in use today as an alternative to the modern Outeniqua Pass (N9 & N12), should one wish a scenic drive on a mist free day.

The Montagu Pass (Illustrated Guide to the Southern African Coast)

Oudtshoorn, in the Klein Karroo, became the centre of the Ostrich feather trade from 1875 to 1914 and there were two boom periods, the first between 1875 and 1885 and the second between 1903 and 1914. The latter was the bigger and many fortunes were made, however the bust came shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, when fashions changed and the ostrich farmers went bankrupt.

Interestingly Oudtshoorn became known as “Little Jerusalem” as the feather trade attracted many people of the Jewish faith as buyers and salesmen. They came from Lithuania where there had been pogroms against them and they sought a new life in the Cape. They spoke Yiddish, a dialect of German which was not too dissimilar to the dialect of Dutch (Afrikaans) which the farmers spoke, thus the new immigrants could easily learn the local language.

Oudtshoorn and its surrounding towns were prospering and were eager for railway communication but alas they were bypassed by the Cape Government Railway (CGR), when the CGR extended its main line from Worcester, up the Hex River valley, towards Kimberley by way of Beaufort West (by 1882). Oudtshoorn again missed its chance when the privately owned Cape Central Railway (CCR) built a branch line from Worcester to Roodewal (now Ashton) via Robertson. The line followed the course of the Breede River and was completed by 1887. An extension of the line through the Kogmans Kloof Pass to the town of Montagu was proposed, which would have allowed an eastwards extension into the Klein Karroo, however this was thwarted by the decision to extend the railway line towards Swellendam instead, under the aegis of the newly formed New Cape Central Railway (NCCR).

The farmers of the Klein Karroo were disappointed but not disheartened and they instead looked eastwards and were determined to get a rail link to Port Elizabeth (PE); this was accomplished by the CGR’s Midland division, by way of a branch line from the junction on the PE to Graaff-Reinet line at Klipplaat. As elsewhere, the work was delayed for the duration of the Second Anglo Boer War (11th Nov 1899 to 31st May 1902) and the line was finally opened on the 1st March 1904.

Meanwhile the NCCR had been busy extending its line in stages, firstly to Swellendam (by 12th April 1899) and then onto Riversdale, (by 19th Feb 1903) and by 1904 a further extension towards the Gouritz River was underway with Mossel Bay the final goal.

Mossel Bay had a harbour midway between Cape Town and PE and was seen to have the potential for further development, as good harbours were scarce along the Cape coast. As early as 1875 the Cape Government was petitioned by the townsfolk of Mossel Bay for a railway line into the hinterland, towards Oudtshoorn (to tap its wealth), which was similar to the proposals set forth by PE and East London. Mr J. Devonsher Scott, the Chief Resident Engineer at PE was duly sent to undertake a running survey for a possible railway between Mossel Bay and Oudtshoorn. His report given in 1876 was not optimistic, in fact he stated: “Difficulties are two-fold in nature. First, as a possibility of passing the mountain range at all and second the practicability of reaching it from the Mossel Bay side".

What was the reason for his pessimism? The answer lies in the very peculiar topography encountered, which might have been especially intended to discourage railway builders. The shoreline is almost entirely sandy with wind blown dunes just above the high water mark. From these dunes a coastal shelf rises abruptly to a height of 200 to 250 metres and this shelf extends at more or less the same level to the foot of the mountains, 10 to 40 km inland. The mountains vary in height from 1 000 to 1 500 metres with the southerly (seaward) face usually being steep, whereas the northerly side is more gently inclined. Furthermore, passes are in reality, saddles over the range. The Gouritz River, to the west of Mossel Bay, is the only river to have broken through the mountain range and its gorge is long and tortuous. It was considered as a possible way through for a railway but was discounted on the basis that earthworks would be heavy and therefore expensive and not thought practicable. Moreover, the rivers rising in the mountains have, over the millennia, cut into the coastal shelf to form deep ravines; hence any route running parallel to the mountains would entail costly bridgework, while shifting sand precluded building along the shore.

The above gives the background to the problems that would be encountered when the line was under construction, due to the lie of the land. Numerous surveys were conducted and initially a route either wholly or partially through the Gouritz River Gorge held sway, but eventually a route via George and the Montagu Pass was opted for.

Even then the debate was not over as various proposals were put forward with regard to whether or not a rack section should be used on the steepest part of the line or a narrow gauge should be used (as was later the case for the Avontuur line). It was finally decided that the line should be built to main line standards, that is to the Cape Gauge (3’-6”), with curves of 5 chains (330 feet = 100.6 m) and gradients no greater than 1 in 36 compensated.

There still remained the thorny issue of cost, which was estimated at £800 000. A scheme was formulated in which a private company would be enlisted to build and operate the railway and that company would benefit from a subsidy of one third of the actual cost of the construction.

So it was that by the provisions of the Railway Extension Act of 1895, the Grand Junction Railway Company was contracted to build the line from Mossel Bay to Oudtshoorn, via George. The contract was signed on the 13th October 1896 (was that perhaps a Friday?) and work was started immediately from the Mossel Bay end, with a planned completion date of the 2nd August 1899! The three year building programme was far too optimistic and should have been queried right from the start.

By early 1898 optimism had turned to grave doubts, as only 15 miles (24 km) of earthworks had been built around the shore between Mossel Bay and the Great Brak River (not a difficult task) and it was no surprise when the contractor went bankrupt in 1902. At that time the earthworks were near completion, close to George, at milepost 31 (50 km). No start had been made on the bridges over the Great Brak, Malgaaten and Guyang Rivers and the Cape Government was forced to take over the work. Work recommenced during October 1904 and the line as far as George was opened to great fanfare on the 25th September 1907.

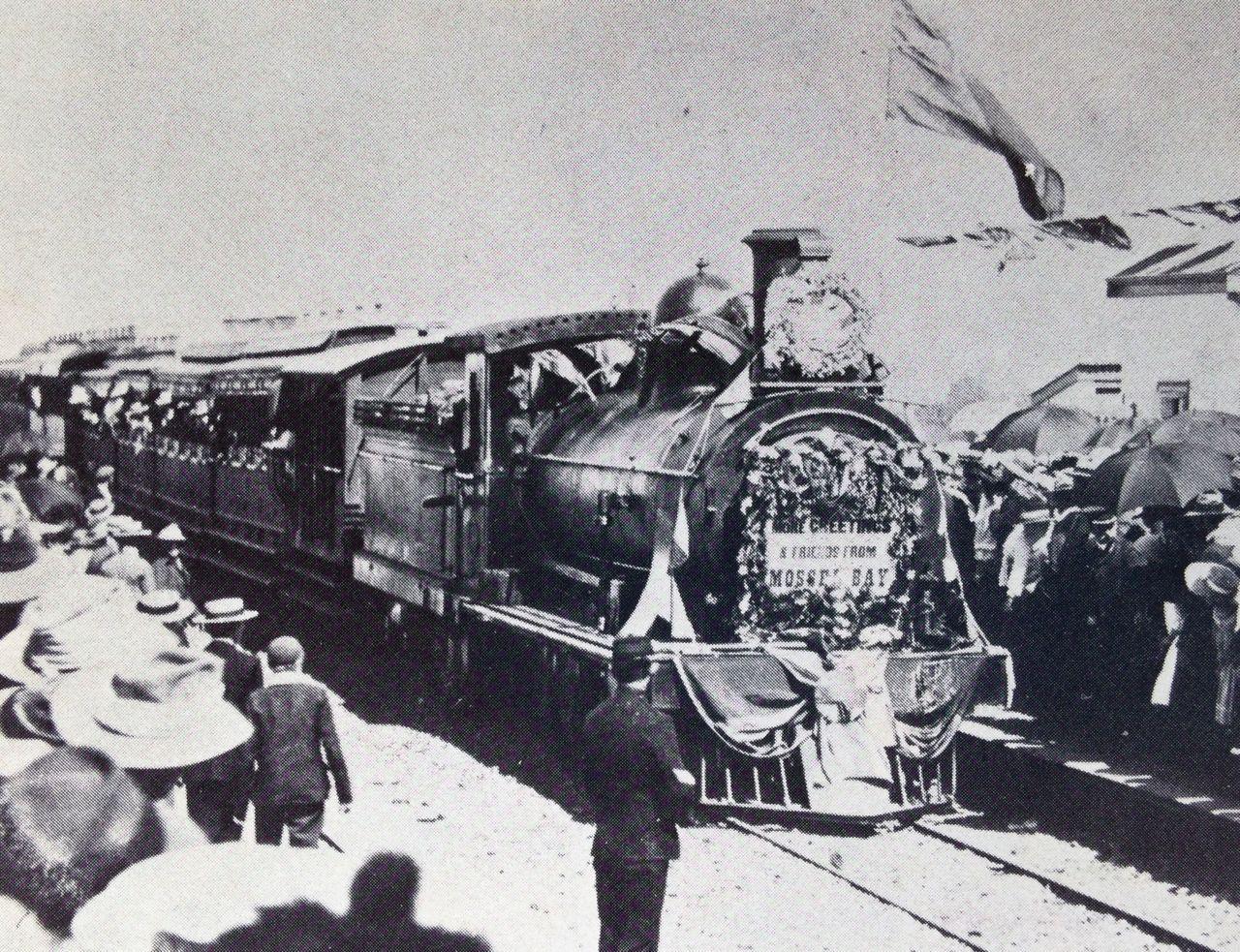

The first train from Mossel Bay to George arriving at George (Railways Southern Africa July 1977)

The NCCR had by then already reached Voorbaai Junction, just to the north of Mossel Bay and, by prior arrangement with the Cape Government, was handed the operation of the line until such time the line over the Outeniqua Mountains was completed.

The long awaited commencement of the building of the railway line over the Outeniquas, was begun on 1st December 1908 (just over a year after the railway had reached George). Convict labour was at first used but during 1910 free labour was brought in. That was also the year of the Act of Union and the establishment of the South African Railways (SAR), after which rapid progress was made. The line was engineered by Mr. T.H. Watermeyer and it took four and half years to complete at a cost of £465 000 (against an estimate of £350 000). The work had entailed the blasting of tunnels, of cuttings, of shelves and the casting of concrete culverts, viaducts and retaining walls and the laying of the permanent way (ballast and track).

It was one of the most difficult sections of railway line to build (and operate) in the whole of Southern Africa rising 2 345 feet (715 metres) in one continuous climb of 15 miles (24 km) from George to Topping (the summit), with a maximum ruling grade of 1 in 36 compensated. The line was to share the name of the original road pass and be known as the Montagu Pass and was finally opened on the 6th August 1913, thirty-eight years after the first petition for a railway had been sent to the Cape Government (in 1875.)

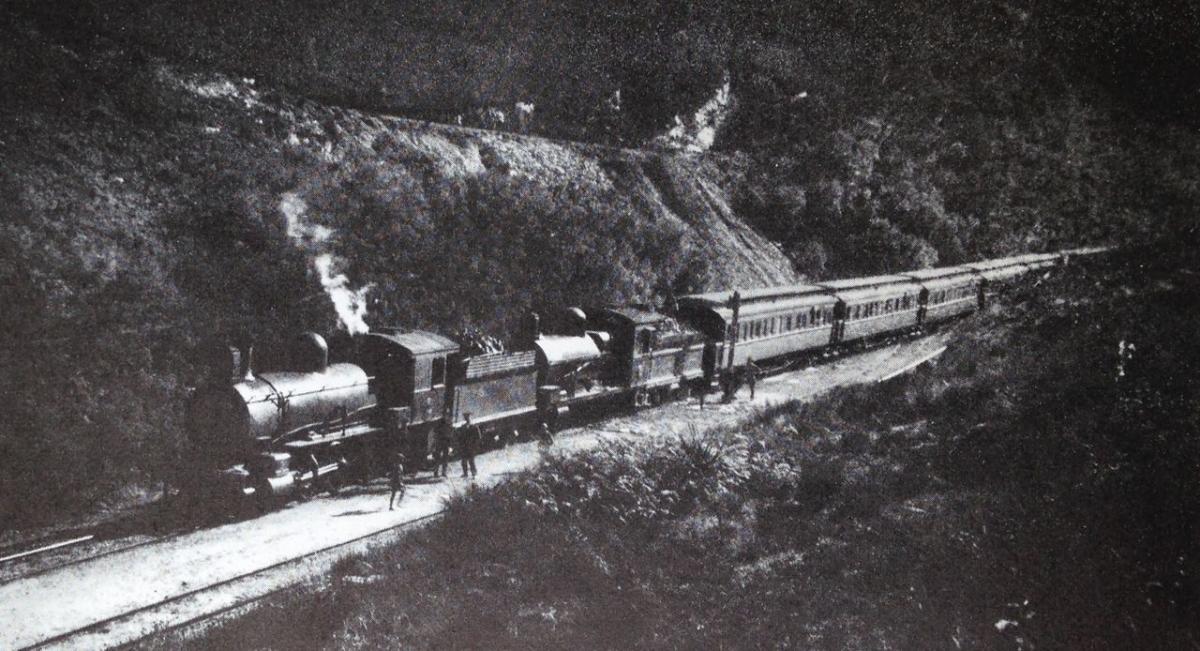

Not ideal railway country - Montagu Pass - (Railways of Southern Africa July 1977)

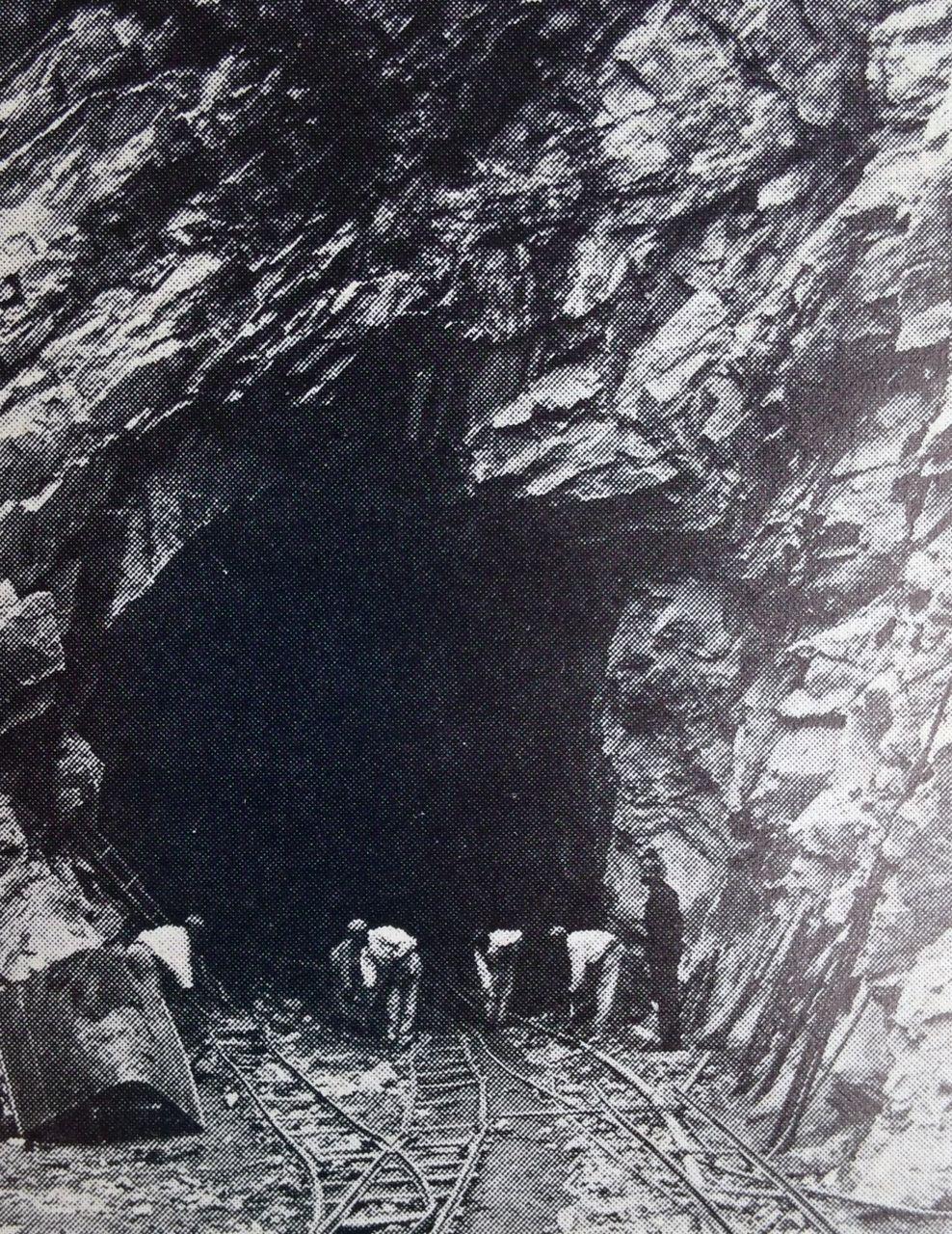

Tunnelling through the quartzite of the Table Mountains series - some of the hardest rock in South Africa - (Railways of Southern Africa - July 1977)

At first it was worked by ex CGR 6th Class (4-6-0) and 7th Class (4-8-0) tender locomotives, which were comparatively small engines and a train required to be double-headed (two locos coupled together at the front of the train). This caused unhealthy conditions in the cab for the driver and fireman, due to smoke inhalation whilst going through the tunnels.

It was only when the Beyer-Garratt locomotive (two engines powered by one big boiler slung between the engines) was introduced in the early 1930’s, that the conditions on the footplate improved for the engine crew; as the engine could be run cab first with the chimney behind. The first successful “Garratt” type (denoted by the letter ‘G’ in the SAR scheme) to be used on the Pass was the GD, which had a wheel arrangement of 2-6-2 + 2-6-2 and a Tractive Effort (TE) of 31 690 lb (at 75% Boiler Pressure). When slogging up the pass it would need a banking engine, pushing at the rear of the train. The GD soldiered on until 1946 when it was superseded by the huge GEA which had a wheel arrangement of 4-8-2 + 2-8-4 and a TE of 55 620 lb (at 75% BP); this machine could deal with 500 tons or 14 coaches unassisted. It was hand stoked so the climb up the pass was always tough work for the firemen. They in turn were displaced in 1975 by the GMAM, 4-8-2 + 2-8-4 (built in 1955) with TE of 60 700 lb (at 75% BP), which had a mechanical stoker, Amen. This type of locomotive would close the chapter on steam power over the mountain. Interestingly enough the maximum loading of a train was not dictated by the Pass itself but rather by a nasty 6 mile (10 km) bank on the eastern side of the Great Brak River, between Mossel Bay and George, which twists and turns with gradients of 1 in 40 uncompensated.

Garratt in the Outeniqua Mountains (The Great Steam Trek)

By the early 1980’s dieselisation was superseding steam nationwide and the services across the Montagu Pass, notably the Cape Town to Port Elizabeth passenger train (which took two nights to complete the journey) was to be hauled by Class 34 diesel-electric locomotives. It so happened that the train to Cape Town crossed with the train to PE at Camfer, on the north side of the mountain, at 11:00 am. It was thus possible to get on board the train at George station at 10:00am and take a journey up the Pass and then change trains at Camfer and come back down again. Although passenger trains have long since been discontinued it is still possible to do the trip up and down the pass by travelling in a four wheeled power car.

The amazing aspect of the Mossel Bay to Oudtshoorn Railway (which includes the Montagu Pass) is not that the line took so long to build, but that it was built at all. The volume of goods and passenger traffic that was forecast never materialised and had the building of the line been delayed any longer, say until after the First World War, the advent of the motor vehicle would have probably rendered it unnecessary.

The Outeniqua Pass - the modern tarred road over the mountain on the western slopes of the Malgas River valley, across from the Montagu Pass - was only begun in late 1942 and was opened in 1951, until then motor vehicles had to struggle up the narrow gravel road over the “old” Pass, travelling adjacent and under the railway line, cautious of oncoming traffic.

Today, should you take a scenic drive along the “new” tar road and you wished to stop at a look-out point, you could look eastwards across the valley and see both Montagu Passes, road (of 1847) and rail (of 1913), as well as the Craddock’s Kloof Pass (of 1812) snaking their way up the steep southern slopes of the Outeniqua Mountains; certainly a sight to behold.

References and Further Reading

- “Illustrated Guide to the Southern African Coast” by the A.A. of South Africa.

- “The Garden Route: South Africa’s Eden” 1980 edition by David Steel.

- “Early Railways of the Cape” by Jose Burman.

- “The Great Steam Trek” by C.P. Lewis and A.A. Jorgensen.

- “Mossel Bay to George: the line that took 38 years to build!” by Roger Fairfax: RAILWAYS Southern Africa, July 1977.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.