Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below reveals the growth and development of the city of Port Elizabeth, known today as Gqeberha. It was written by Franco Frescura in 1992 during the transition to democracy in South Africa.

The social system that was implemented in this country after 1948 was known internationally by its euphemistic name of “Apartheid”, or “Separate Development”. This was of undoubtedly evil intent, but since 1994 there has been a tendency to minimize many of its policies and reduce them to a simple generic term. This has not taken place because of any wish to hide the true nature of Apartheid, but probably out of a wish to move on with the process of nation building, as well as a need to bring a greater degree of normality into our lives. While this may be a positive outcome of the Truth & Reconciliation Commission (TRC), there has been a danger that many of our memories will soon be relegated to a closet of inconvenient truths and nightmares which few of us wish to constantly revisit. This has left an open and fertile ground for some politicians and fellow travellers to reinvent Apartheid in their own image guided not by established historical facts but by whatever is expedient to present as “Apartheid” at that particular time.

I believe that, in the spirit of the TRC we, as one of the generations that has lived through and under Apartheid, ought to record our memories of those days, if for no reason other than a wish to register the subtle words, attitudes, and memories of our time, and the reasons why Apartheid was such an abhorrent concept. Racism had many facets and could present any number of nuances, and perhaps many of us grew to accept some practices not out of any wish to hide them but because they were so much part of our everyday lives that some words or acts were so unavoidable that to fight their injustice would have required living in a state of constant anger. And, as I still remember, there was and still is a lot of anger to go around!

This essay arises out of a personal need to discuss some of these nuances. It deals with my experience of Port Elizabeth as a case study, and attempts to contextualize my experience as a resident of a city where I lived for nearly ten years. Inevitably, during the course of researching its early history I came across a number of facts which were unique to the place and could only be explained in terms of its unique history. On the other hand, many of these events were repeated, in a different form in other parts of the country, and thus assist in the creation of a wider pattern of behavior we describe today as “urban segregation”. It is in this light that this history has been written, and has been presented here out of a wish to describe more fully the behavior of our ancestors who, when faced with the presence of strangers, immigrant and local, and whose behavior was totally alien to their societies, took measures which may or may not have made sense at the time of their encounters.

A History of Early Segregation

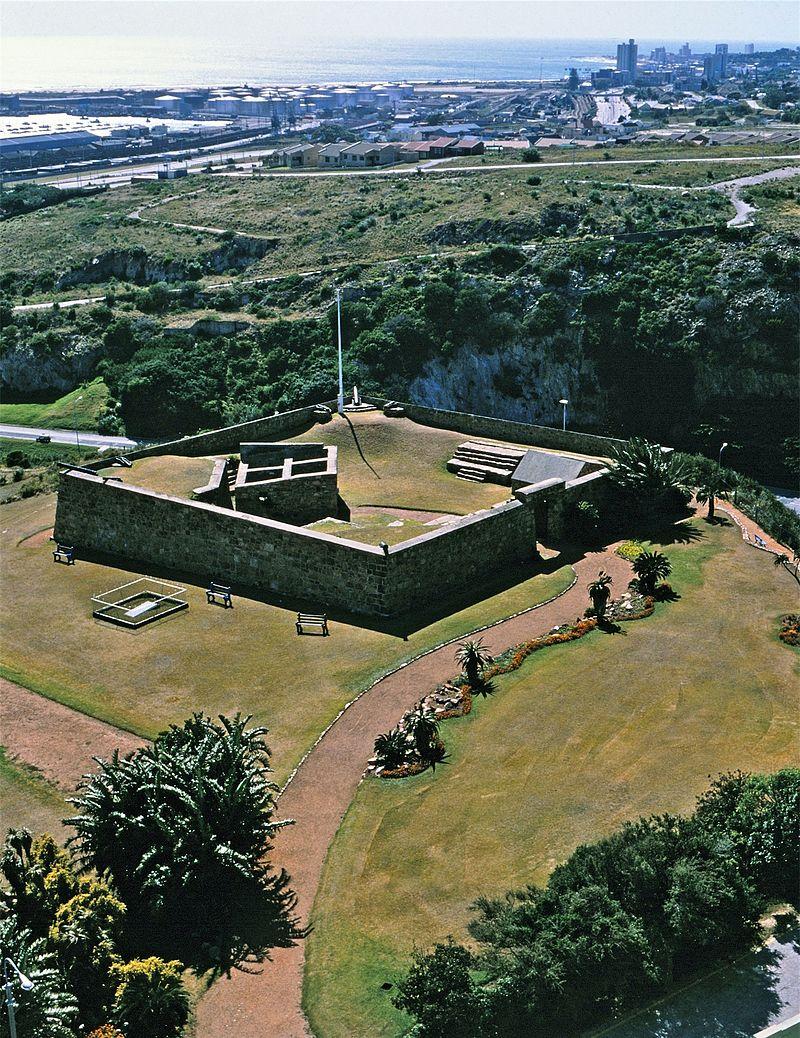

The first immigrant structure in Port Elizabeth was erected by the British in August 1799. Named Fort Frederick, after Frederick, Duke of York, its main function was to guard the landing place and water supplies at Algoa Bay. It is also probable that the British intended to establish a military presence in the region to deter potential Dutch uprisings in the district of Graaff-Reinet, and to protect Cape Town, and hence the India sea route, from possible French attack. The township of Port Elizabeth was laid out in 1815, but was not developed until 1820 when some 5000 British settlers arrived in the Eastern Cape.

Fort Frederick Port Elizabeth (Janek Szymanowski)

Initial settlement focused upon the harbour as the town's major area of economic activity. However, as the bay’s micro-climatic factors began to exert themselves upon the settlement, so then the residential areas of columnists began to move to cooler and less humid higher ground overlooking the bay, and into areas which provided a measure of shelter from winds that blew persistently throughout the year. Initially the economic development of the village was slow, and James Backhouse who visited the place in December 1838, described it as follows:

Port Elizabeth is situated on the foot of a steep hill, at the margin of Algoa Bay; it is much like a small, English sea-port town, and contains about 100 houses, exclusive of huts; the houses are of stone or brick, red-tiled, and of English structure. The town is said to have been chiefly raised by the sale of strong drink.

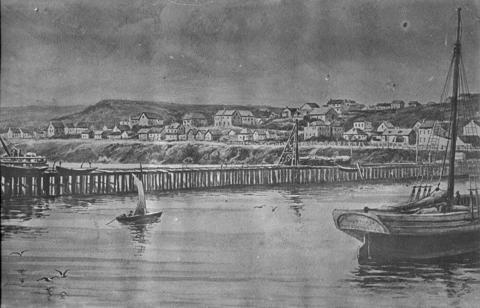

Thus at its onset Port Elizabeth served predominantly as a service centre for the agricultural hinterland of the Eastern Cape. Its basic function was to handle, and later process, goods and materials passing through its harbour. However, developments elsewhere in the southern African interior provided economic stimulus to the new town, and by the 1860s it had overtaken Cape Town as the Colony's premier port. The growth of an ostrich feather industry in Graaff-Reinet, Oudtshoorn and the Albany, the discovery of diamonds in the northern Cape and gold in the Transvaal, and the outbreak of successive wars against the baSotho, the Griqua, the baPedi, the baTswana and the Boer Republics, were all to benefit Port Elizabeth. As a result numerous manufacturing industries began to be established locally, and during the early years of the twentieth Century the town became a focal point for food processing, motor vehicle assembly, and a variety of associated industries, which created extensive employment opportunities. This, as well as increasing rural poverty in the region, attracted many workers to the town to the point that, until the 1960s, it maintained its place as South Africa's third largest urban centre.

Sketch of jetty at Port Elizabeth Harbour in the 1860s (DRISA Archive)

Colonial Segregation

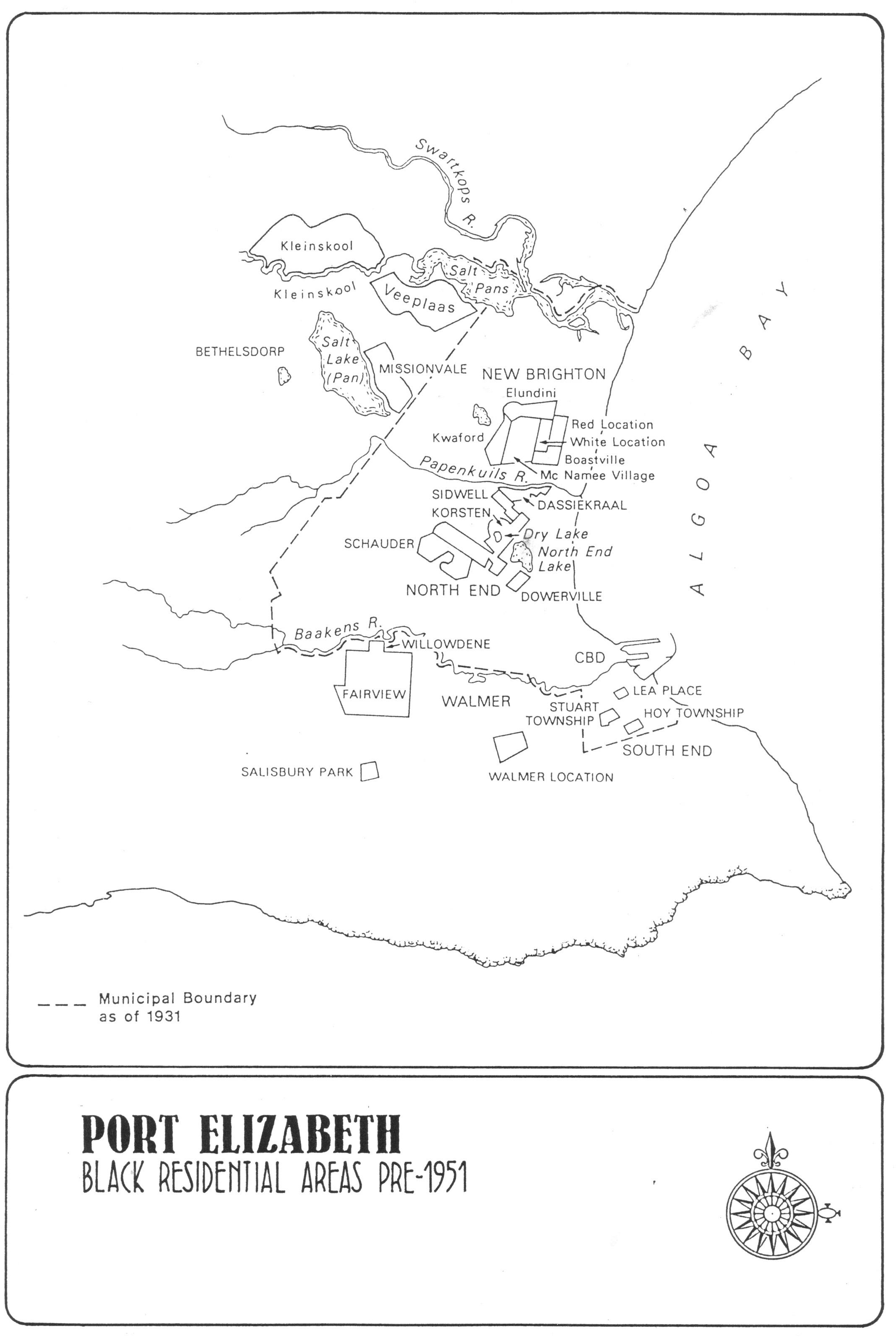

Port Elizabeth, as it stands today, owes its urban form to a number of physical and historical constraints. However, since the early 1900s, colonial segregation planning and a policy of statutory racial separation implemented after 1950, has resulted in what has become a prototypical model of the "apartheid city".

The early population of Port Elizabeth consisted, in the main, of European immigrants, as well as persons of mixed race which the apartheid system subsequently labelled as "Coloured". A small minority consisted of persons of so-called "Cape Malay" and “Asaian” origin, including Indian and Chinese. Initially few members of the indigenous population were attracted to the town and, almost from the onset, economic status was related to skin colour. Whites held a virtual monopoly over higher paid jobs and consequently could afford better housing in areas which were usually physically removed from "other" groups. Thus economic segregation was an integral part of early Port Elizabeth, with the population of industrial areas, such as South End and North End, being predominantly of mixed race and Asian origin, while the residents of its central and western suburbs were mainly European. However, while white attitudes to Coloured and Malay citizens remained relatively tolerant, official policies toward indigenous residents were markedly different.

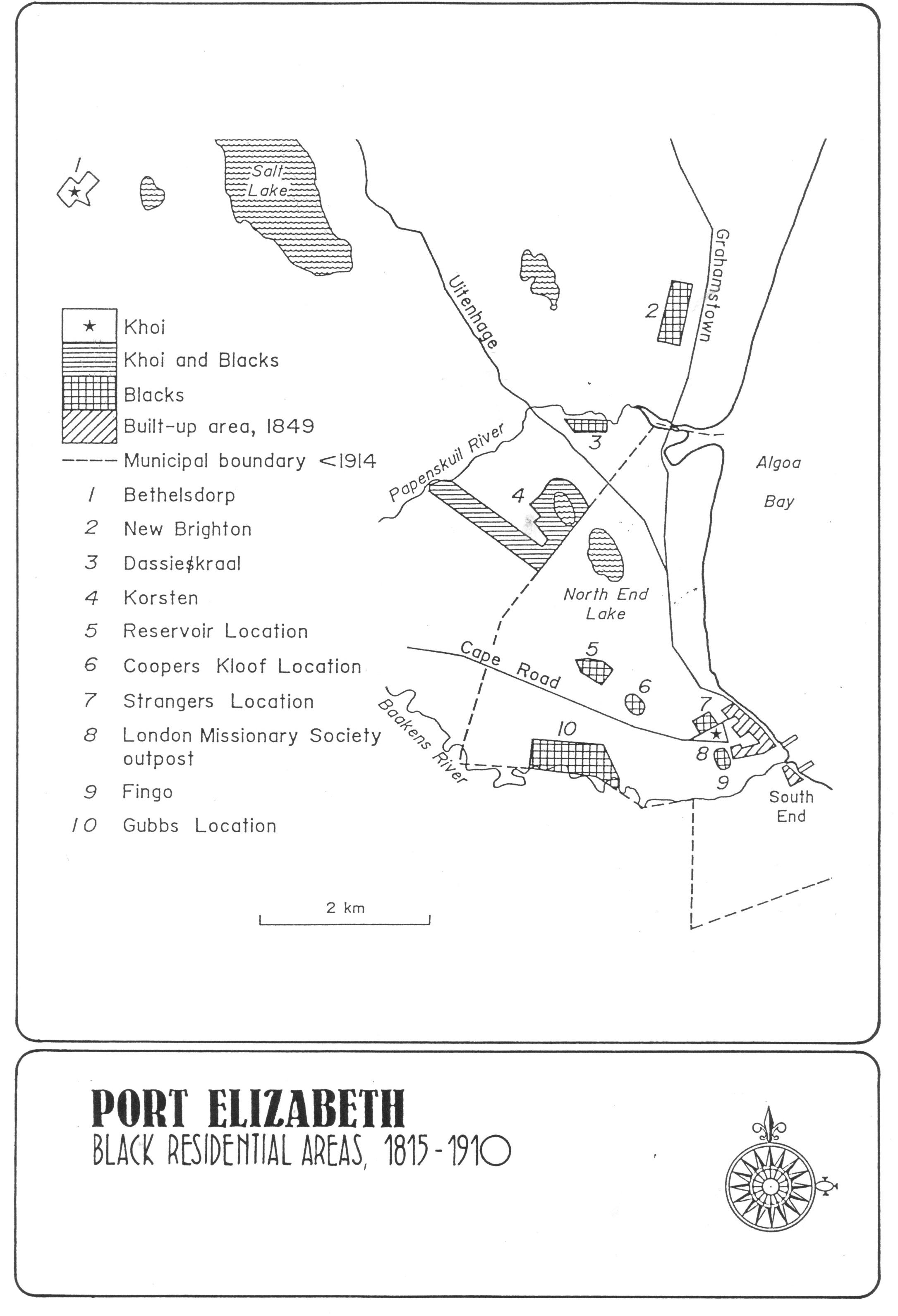

Thus, as a rising number of black workers began to enter Port Elizabeth seeking employment, so then a number of so-called "locations" began to be established on the outskirts of the white suburbs. Rosenthal has defined locations as being: "Large Native Reserves as well as small areas in municipalities earmarked for residence by Africans." (1970)

The pattern was first established in 1834 when the Colonial Government made a grant of land to the London Missionary Society (LMS) to provide a burial ground and residential area for "Hottentots and other coloured people who were members of the Church" (Baines, 1989). This was located at the crest of Hyman's Kloof, better known today as Russel Road. Other workers however chose to erect their homes closer to their places of employment, or where a supply of potable water was available. The major Black suburbs of that time were:

- Bethelsdorp - 1803

- Fingo and Hottentot Location - 1830s

- LMS Outstation - 1834

- Dassiekraal - c1850

- Korsten- 1853

- Stranger's Location - 1855

- Gubbs Location - 1860

- Cooper's Kloof Location - 1877

- Reservoir Location - 1883

Bethelsdorp

With few exceptions these Black suburbs were informal in nature, and residents there were forced to endure living conditions which some contemporary observers described as being squalid and open to exploitation by capitalist landlords. Many whites considered them to be unhealthy and petitions were repeatedly organised demanding that they be removed to the outskirts of the town. These requests were in direct opposition to the needs of the growing commercial and industrial sectors which preferred to locate their labour sources close to the harbour and the inner city area. These conflicting vested interests created political tensions within the Port Elizabeth Town Council which were only resolved in 1885 when the Municipality adopted its first set of markedly segregationist regulations.

As a result, suburbs for the exclusive use of black residents who were not housed by employers, and who could not afford to purchase property, were established on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth. Most prominent amongst them were:

- Racecourse - 1896

- Walmer - 1896

- New Brighton - 1902

In 1901 an outbreak of Bubonic plague struck the town. This was the direct result of Argentinian horses and their fodder brought into South Africa by the British military during the South African War of 1899-1902. These imports also carried plague-infected rats, and although many members of the White and Coloured communities were also affected, the brunt of the Plague Health Regulations were borne by the black population. In 1902 most of Port Elizabeth's old locations were demolished (with the exception of Walmer Township), their resident's personal belongings were arbitrarily destroyed, and restrictions were imposed upon all forms of inter-town travel. Although these curbs might initially have been necessary, they were only loosely applied to white residents, and continued to be strictly enforced upon the lives of black residents well after they were eased elsewhere. This was done in the face of repeated complaints by the community's leaders.

Because New Brighton was located relatively far from the town centre, many families preferred to settle in Korsten which, at the time, was beyond the Port Elizabeth municipal boundary, but was still substantially closer to town. In addition, the suburb did not enforce stringent bye-laws upon the domestic brewing of beer, an activity which, at that time, was an important source of revenue for the black community.

During the colonial period therefore, the location system created a pattern of residential segregation based upon perceived racial and economic differences. However such divisions proved to be only partial, and it was only the implementation of Group Areas legislation after 1950 which brought about a structural separation of Port Elizabeth's residential areas. None-the-less it was during this time that the seeds of the Apartheid City were sown.

Post-Colonial Segregation: 1910-1950

By 1950 the population of New Brighton had grown from 3,650 in 1911 to 35,000. Almost all of this took place in the black community. This polarisation was reinforced by the Native Urban Areas Act of 1923 which required municipalities to establish separate locations for their black citizens, and made black residents in "white" areas subject to a permit system which Apartheid legislation subsequently extended into the now-infamous “dompas”. The Native Land and Trust Act of 1936 also precluded blacks from purchasing land outside areas designated for black occupation. Although this legislation was primarily aimed at the regulation of urban areas, it had enormous impact upon rural areas where a class of emerging black farmers had begun to purchase back ancestral land which immigrant white farmers had originally dispossessed in the early years of colonial conquest.

In addition, existing suburbs, as well as new housing projects for whites in urban areas began to include racially restrictive clauses in their title deeds. In this way most of Port Elizabeth's western suburbs were reserved for exclusive white occupation, although the presence a scattering of Chinese families was quietly tolerated.

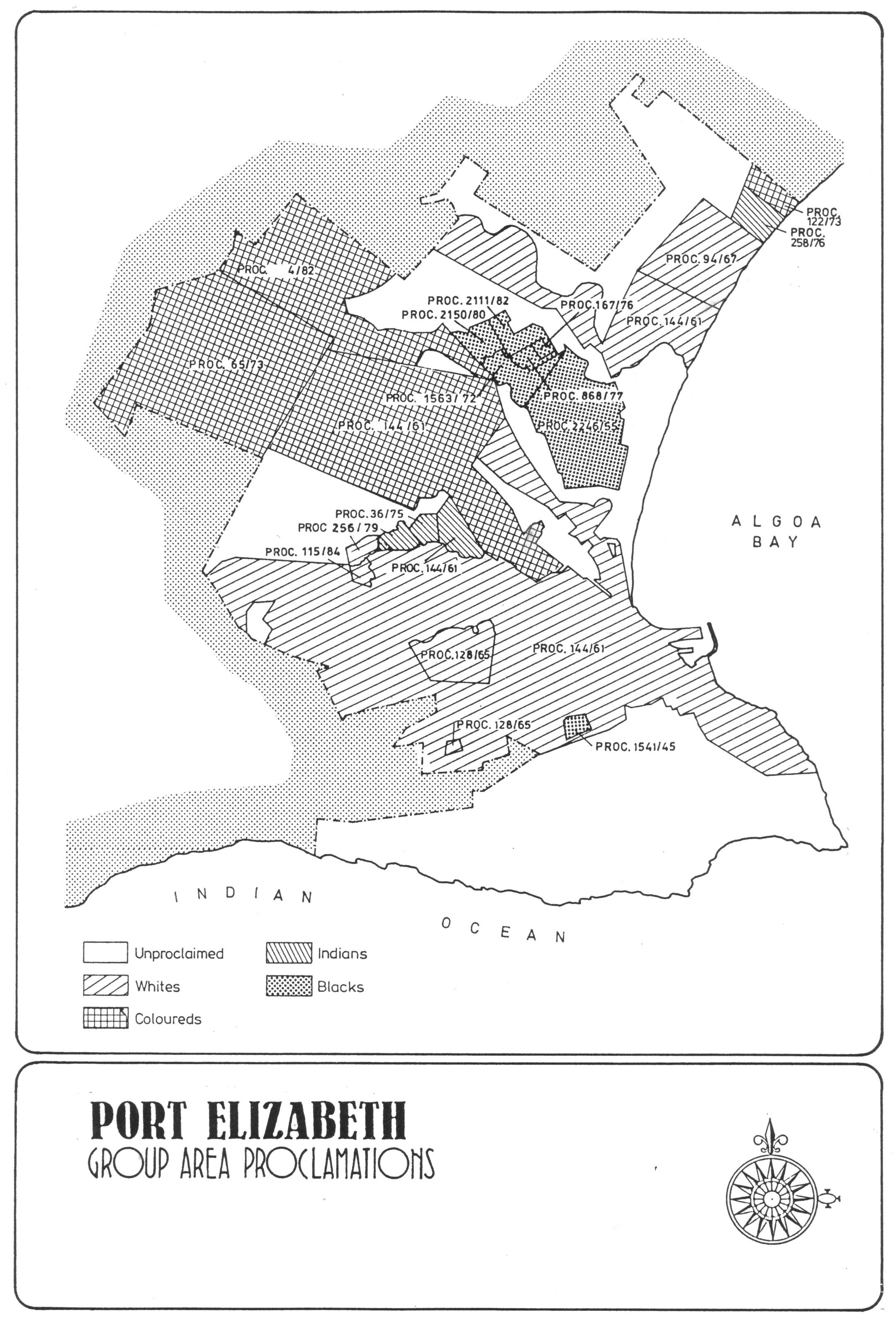

Apartheid Ideology and Implementation from 1950 to Date

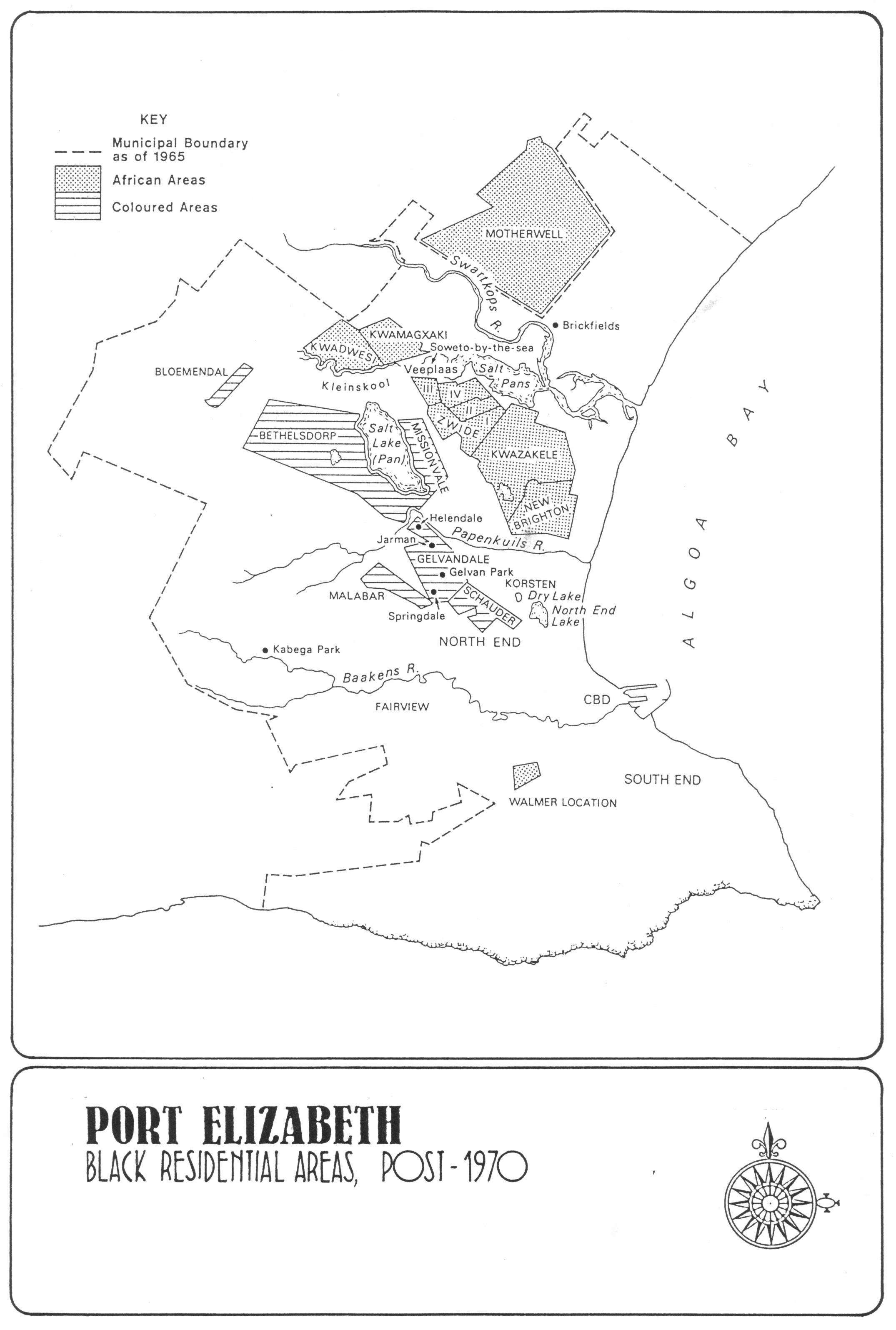

When the Nationalist Party came to power in 1948, the City of Port Elizabeth underwent a number of extensive changes in its land use patterns through the implementation of racially-motivated segregationist legislation. This included the separation of citizens into so-called "White", "Bantu", "Coloured" and "Asian" suburbs. Apartheid legislation laid down that such areas should be set apart by buffer strips at least 100m wide. These often coincided with existing physical barriers. As a result, industrial areas such as Struandale, and natural features such as the Swartkops River and its escarpment, and pieces of empty land such as Parsonsvlei, were used to define the parameters of the city's suburbs.

It is important to note that apartheid ideology did not view black workers as a permanent component of urban life, but held that, at some stage, they would return to some mythical rural "homeland", presumably of their own initiative and free will. This is an attitude which, in later years, was to have important political repercussions. Not only did it relate directly to the quality of so-callewd "Bantu" education, which in turn sparked off the Soweto student uprising of 1976, but it also created residential conditions which will take many years, and a substantial proportion of the national budget, to eradicate. Because of this, black access to land tenure, quality housing, infrastructure, social amenities and economic opportunities was severely curtailed.

Black suburbs were developed on the remote outskirts of the city making daily travel to the workplace expensive. Also, for some years, little retail and business development was permitted within the bounds of townships (as they began to be called), forcing residents to conduct the bulk of their retail shopping in the central city area which, of course, remained in White ownership and control. The Apartheid City thus did not merely seek to beggar its Black citizens, it also entrenched in its fabric a "company store" relationship existing between its black suburbs and the white-controlled CBD.

Matters did not change substantially after 1981 when the Government acknowledged the permanent status of urban Black communities and put in place an Ibhayi Town Council which would administer Port Elizabeth's Black suburbs as a separate municipality. At this stage, the zoning of all industrial, retail and business development within the boundaries of a neighbouring white Port Elizabeth ensured that the two Municipalities did not share equally in the city's tax base. This is one of the mechanisms whereby Port Elizabeth's black residents continued to subsidise the white community in its expensive segregated lifestyle.

The process of apartheid expropriation, relocation and residential control had the effect of increasing New Brighton's population from 35,000 persons in 1951 to 97,000 in 1960. As a result KwaZakele was established in 1956, and following the demolitions of Salisbury Park, Fairview and South End in the late 1960s, the black township of Zwide was declared in 1968. After the Government brought its programme of intensive subsidised housing, which it initiated in 1952, to an end in the mid-1970s, increasing pressures of urbanisation brought about the additional establishment of Motherwell in 1982 as yet another independent municipality.

It also needs to be borne in mind that although the Nationalist Government single-mindedly pursued a policy of racial segregation in the case of white areas, it tended to ignore racial mixing and even intermarriage in other communities. Thus, even though new segregated suburbs such as Gelvandale, Bethelsdorp and Bloemendal were established for exclusive Coloured occupation, and Malabar was set aside for Indians, some areas such as Korsten which, historically, had enjoyed a mixed population, retained much of their integrated character well into the 1980s. Other mixed communities, however, such as those living in Fairview and South End, were not so fortunate, and in their case their residents were forced to relocate, often under armed police guard, to new segregated areas, while their properties were expropriated and either bulldozed to the ground or sold to members of the White racial group, usually for a fraction of their value. This practice was established in 1952 following legislation passed by the Union Parliament, and was carried out by a Government Department euphemistically known as “Community Development” under the political leadership of a Nationalist Party Cabinet Minister, Blaar Coetzee. Even in its time this policy was compared by many to the action of the Nazi Party in Germany after 1933 when, in an effort to remove and eventally murder all German Jews, the German state set about their systematic removal, and the expropriation of their properties. Artworks, precious furniture, jewels, land, buildings and businesses were expropriated for a pittance of their worth and then sold off to German residents who could show proof of pure Aryan heritage.

On the other hand, in Port Elizabeth, it is important to record that, throughout the colonial, segregationist and apartheid eras the original mission settlement at Bethelsdorp remained a major focus of Khoikhoi and, later, black resistance to segregationist efforts by the Apartheid government.

Conclusions

It is clear that although the Group Areas Act was repealed in 1991, the component elements of Apartheid planning have been indelibly etched into the urban fabric of our cities. It is probable that their effects will continue to be felt for many years to come, and that their traces may never be entirely expunged from the South African urban fabric.

Changes are not likely to take place through a long-term, liberal, free-market exchange of land, but will probably require a series of stringent land and price controls orchestrated through a city government committed to strong democracy, community empowerment and the generation of wealth. This is not a philosophy likely to find favour with the broad white electorate, nor with white Liberals or the country's neo-Democrats, all of whom have benefited extensively from the implementation of Apartheid's economic measures. However the Apartheid City was the creation of a doctrine-driven central government, and was only achieved through the imposition of extreme hardships upon the black community. These families are now entitled to a form of restitution, and one of the ways in which this could take place is through an improved quality of housing, of life and of economic opportunities.

To use an architectural metaphor, the edifice of apartheid was only made possible by a structure, a scaffolding, of inter-supporting laws, edicts and social practices. Once the building was completed and could stand alone and unassisted, then the scaffolding could be dismantled and removed. It is true that, after 2 February 1990, the Nationalist Government began to remove the legal props to apartheid, but the substantive structure of economic inequality inherited from that system is still very much in place. Its granite face will not be affected by rubber mallets, but will require a demolition tool made of a sterner materials.

This also means that the planning profession will have undergo severe structural changes if it is to meet the needs of a future democratic South Africa. It is clear that, in the past, it was the work of planners that gave Apartheid ideology its physical dimensions, and permitted its implementation on the ground. The design of radial roads, limited access townships, cordons sanitaire and segregated facilities reveals a totalitarian mind-set reflective of an oppressive and unjust society. It is now up to the new generation of town planners to reconcile the mistakes of the past with the realities of the future, and help our people achieve the greatness they deserve. I wish them well in their endeavours.

Franco Frescura - Professor and Honorary Research Associate, University of KwaZulu-Natal - frescuraf64@gmail.com

Bibliography

- Baines, G. 1989. The Control and Administration of Port Elizabeth's African Population, 1834 - 1923. CONTREE. 26. 12 - 21.

- Baker, Jonathan. 1990. Small Town Africa - Studies in Rural-Urban Interaction. Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Backhouse, James. 1844. A Narrative of a Visit to the Mauritius and South Africa. London: Hamilton, Adams.

- Caldwell, Sharon Edna. 1987. The Course and Results of the Plague Outbreaks in King William's Town, 1900 - 1907. BA Hons Treatise, Rhodes University, Grahamstown.

- Christopher, AJ. 1991. Port Elizabeth Guide. University of Port Elizabeth.

- Clayton, AJ. 1986. Facts and Figures. Port Elizabeth: City Engineer's Department.

- Del Monte, Lance. 1991. One City Concept: Land Use. Port Elizabeth: Metroplan.

- Frescura, Franco and Radford, Dennis. 1982. The Physical Growth of Johannesburg. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- Infraplan. 1988. Port Elizabeth Metropolitan Study. East London: INFRAPLAN.

- Lemon, Anthony. 1991. Homes Apart. Cape Town: David Philip.

- Oberholster, JJ. 1972. The Historical Monuments of South Africa. Cape Town: NMC.

- Rosenthal, Eric. 1970. Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. London: Frederick Warne.

- Strategic Facilitation Group 1991. Development Facilitation. Port Elizabeth: SFG.

- Taylor, Beverley. 1991. Controlling the Burgeoning Masses: Removals and Residential Development in Port Elizabeth's Black Areas 1800 - 1900. Working Paper No 51. Grahamstown: Institute for Social and Economic Research.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.