Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

1845... The railway age is in full swing in Britain. Robert Stephenson is completing the line between London and Edinburgh. Brunel is extending his line into Cornwall and is tinkering with the atmospheric railway. New railway companies are springing up, and contractors are working all over England. There is money to be made, directly and indirectly from building new lines. In America the network east of the Mississippi is growing and there is talk about accessing the harvests of the prairies with railways.

If there is a railway boom in England, and there is money to be made by exploiting the agricultural potential of America, are there not opportunities for investment in other parts of the world? What about that backward little colony at the foot of Africa? It’s apparently bankrupt, but it does produce wheat and fruit and make wine, and could perhaps trade in wool and meat as well, and it's comparatively well placed for trade with Europe. Pity about the lack of a proper harbour, and the appalling roads, though. But it might be worth the investing one of these new-fangled railways to solve the transport problem!

And so in 1845 a committee met in London to form a company to promote railways in South Africa.

Things were looking up in the colony. The new Colonial Secretary, John Montagu, had sorted out the financial mess and was turning his attention to roads. He even had a plan to solve the labour problem by putting convicts to carry out public works. There was a new spirit of enterprise and optimism in the sleepy little country.

John Montagu

But John Montagu's heart was in the mountain passes and the hard roads, and he saw no need for any alternative form of transport - and what he said went - and that wasn't a train. So until he was out of the way there was little point in persisting. The company was stillborn.

In 1853, when Montagu had retired, another group of London businessmen formed the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company, and they appointed Sir Charles Fox as its technical advisor. Fox was a very competent engineer, the founder of the firm known in later generations as Freeman Fox, whose lasting monument is the Sydney Harbour Bridge. He had worked on railways but had made his name with the engineering design of the great Crystal Palace building. Within a year an enthusiastic and relatively influential South African Committee of the company was formed and they persuaded the Government to consider building a railway. The Colonial Engineer, Capt Pilkington, did a rough survey of a possible route to Wellington and showed that the plan was feasible.

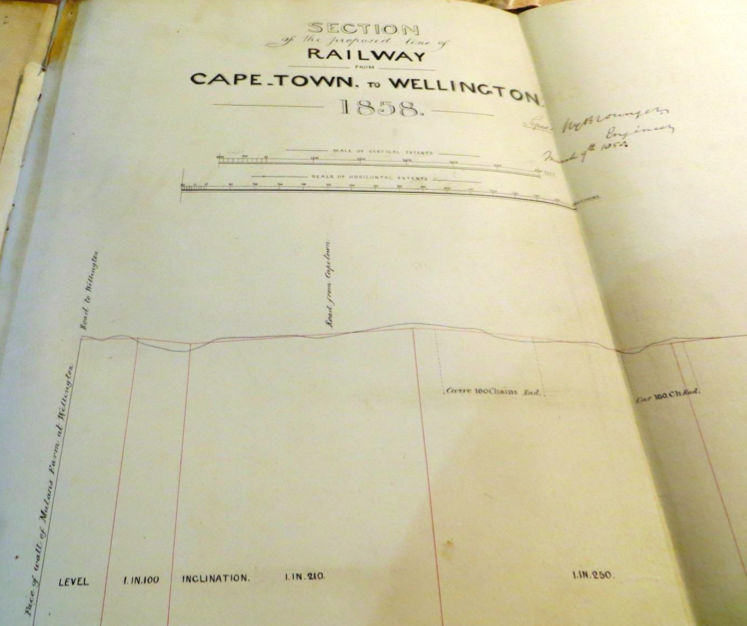

Section plan of the proposed railway line from Cape Town to Wellington

At this stage another London-based group seized the initiative. They sent out John Scott Tucker, a young engineer who had worked with Brunel and had recently been building railways in Brazil. He gave evidence to the parliamentary commission which had been formed to consider the planning of railways in the Colony, and he convinced them that the best way forward would be for a line to be built by private enterprise. However for a company to succeed it would need to be guaranteed 6% return on investment by the Colonial Government. The politicians agreed to these terms, but Tucker's principals were unable to put together sufficient shareholders to take advantage of his proposal. So back came the Cape Town Railway and Dock Company, and Fox sent out his star pupil to do a detailed survey and prepare a tender for a railway. The engineer was William George Brounger and his scheme was accepted in October 1858.

William George Brounger

Brounger was born in Hackney in 1820. He was apprenticed to Fox at the time when the London to Birmingham railway was under construction, and obtained his early experience on this job. He must have made rapid progress as he was elected to full membership of the prestigious Institution of Civil Engineers at the age of 29. He then became involved in the design of the Crystal Palace structure for the Great London Exhibition of 1851. The overall concept was the brainchild of Joseph Paxton, a landscape architect by profession, to whom Fox was chief technical advisor. Brounger was employed to produce the detail design, and was warmly praised for his work. The fact that this huge glass structure was erected in Hyde Park, and then was dismantled and successfully re-erected in south-east London is sufficient tribute to his skill in detailing.

Inside the Crystal Palace (Architecture of the 19th Century)

He then returned to railway engineering and was appointed as Engineer-in-Charge on the construction of the line across the Danish island of Zeeland. This prestigious work was generally acclaimed, and with a reputation thus firmly established, Brounger took up his appointment at the Cape in 1857.

Brounger perhaps was not aware of the lack of engineering skills in South Africa at the time, and he soon found that he would have to train assistants from scratch. Surveyors, draughtsmen, permanent-way layers and other skilled workers all had to be identified and taught, and Brounger had to undertake the task himself.

The arrangements between the Company and the Colonial Government were tricky. Officially the railway belonged to the company, but as the Colony had a finger in the pie, the Colonial Engineer had considerable influence. The actual construction was let to a contractor, so a third party was also involved.

William Brounger (DRISA Archive)

John Scott Tucker

Old George Pilkington, the Colonial Engineer who had done the initial survey, retired in 1858, and he was succeeded by none other than John Scott Tucker whose eloquent case for the railway had come to nought. Now Scott Tucker is a bit of an enigma. He was apparently in the forefront of the bright young engineers of his time, but his obituary concludes with the ominous phrase: "he was of amiable disposition which precluded him from reaching true greatness". Did he arrive in this country determined to correct his failings and to act the tough client, frustrated as he had been in his effort to become the father of railway engineering in the Colony? By all events he started to interfere with the progress of the railway and to make a thorough nuisance of himself.

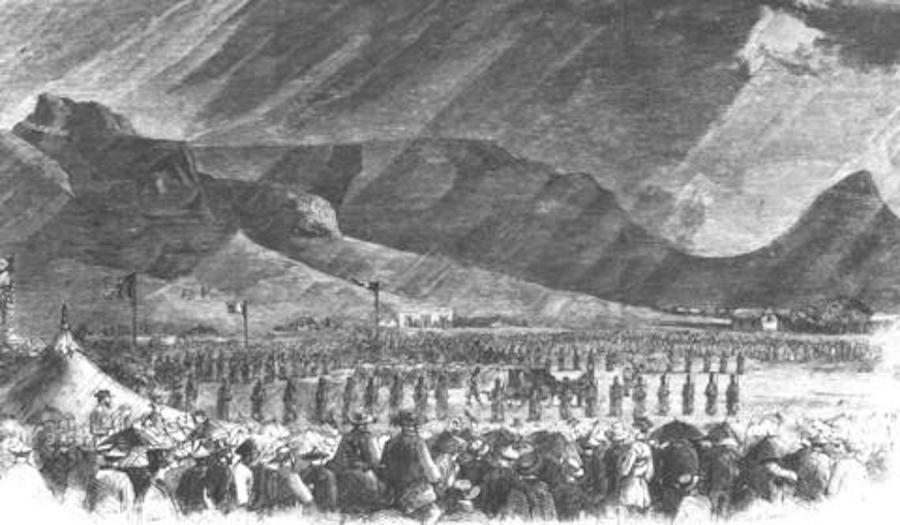

The agreement with the Government was that line would be built from Cape Town to Wellington via Stellenbosch. Sir George Grey turned the first sod at the intended Cape end of the line, near present day Woodstock station amid the usual grand ceremony. The contractor, Edward Pickering, actually began work at the Wellington end.

Almost immediately Parliament proposed that the line be extended to the centre of Cape Town, and Brounger claimed that this was not in the contract. So an extension was entered into, by which the line would terminate on the Grand Parade on an area bounded by Adderley Street, Castle Street and Strand Street. Scott Tucker threw his toys out the window. He had not been consulted and he did not agree to the extension. He also questioned the design of the earthworks on the line and insisted that the quantities be increased by over 50% - presumably without additional compensation. Brounger was having none of that and complained to the Lieutenant-Governor. The upshot was that the Colonial Secretary informed the company that Mr Scott Tucker's duties were too numerous for him to give proper attention to the railway work, and the responsible official would now be the Surveyor-General, Charles Bell. At the same time Tucker was released from any involvement with the harbour works which had just got under way (but not under the auspices of the railway company).

Stripped of his most interesting work, Tucker spent his time trying to reorganise the office of Colonial Engineer, which old George Pilkington had left in a rather disorganised state. However, the task proved beyond him, and he eventually recommended that the post of Colonial Engineer be abolished. This was accepted and he returned to England in 1864. Thereafter he undertook consulting work in London and eventually became Superintendent of Public Works in Barbados.

Tucker's most enduring work while in the Colony was the design of the lighthouse on Robben Island, which still exists.

Robben Island Lighhouse

The Durban Railway

While the Cape was involved in organising this relatively substantial railway, the citizens of Durban banded together to promote a modest little railway to connect the Point - where the wharf was located - to the centre of town. It was a time of growth in Natal, with many immigrants arriving and an infant sugar industry beginning to be established. Despite financial problems the little company went ahead with the project, and the first train - an engine and a motley collection of carriages - steamed the 3 km on 26th June 1860. The staff of the company was reported to be a general manager/engineer, a driver and a boy. It may have been little more than a toy train, but Natal can claim the first working railway in Southern Africa.

Into the Boland

Meanwhile the construction of the Cape main line rolled on. Local labour proved unequal to the task, and Pickering recruited 300 navvies in England. They were a mixed bunch – some had genuine experience on English construction, but many were ruffians, drunkards and other misfits who would cause unrest in the workforce. The first locomotive arrived in September 1860 and was landed at the old jetty. One can imagine the problems caused in off-loading a heavy machine from a ship onto a rickety platform with only manpower to take the load, but the job was done without mishap. The driver, William Dabbs, who like his machine hailed from Leith, Scotland, completed the assembly and drove the machine for the rest of his working life. The first trip of the engine took place on 24th October 1860 to a cheering crowd. This was from Papendorp (Woodstock) to Salt River where the main workshops for the railway had been located.

Bell proved a sensible client, though he did move the railway station one block nearer the sea to avoid some trees on the edge of the Parade, thus showing early concerns about environmental matters. And he did have problems with Pickering the contractor, who was plainly inexperienced and incompetent. So the company's consulting engineer, Brounger, found himself doing most of the work. He carried out the design and produced the bulk of the drawings himself, and he meticulously checked anything done by others. Eventually he had to take over the construction as well. When the permanent way was complete he had to take charge of assembling the rolling stock, and finally he had to train the operating staff and work out the scheduling. It was a tremendous achievement for one man to complete successfully.

When Pickering realised that his contract was about to be terminated, he stopped work and discharged all the navvies. This left a huge force of men without visible means of support and far from their native shores. A labour crisis was avoided when the Government arranged for the men to be employed on the breakwater. A few weeks later the railway company announced that it would take possession of all the contractor's plant and materials, and continue construction itself. Now Pickering might have been incompetent but he wasn't stupid, and he immediately began siphoning off as much of the material as possible. So the company sent a force of about 60 navvies to Klapmuts, then called Bennettsville, to retrieve a load of sleepers which was being abducted. Pickering's agent pulled a gun on the junior engineer who was in charge of the posse, blocking the removal of the material. In order to keep the peace the local lawman arrested the engineer! Fortunately the incident blew over.

However, a day or two later, violence broke out at Salt River workshops where company navvies started a fight with those still in Pickering's employ. The war continued for half a day during which some of the track was pulled up and one of the engines (for others had now been landed) was derailed. The company was keeping up its supporters' spirits by supplying them with beer from the nearby Locomotive Hotel, and so the opposition stormed the pub and appropriated the refreshments. A judge had to be called to issue an interdict restraining everyone from touching railway property. Eventually order was restored, a settlement was reached and Brounger took over construction. But the navvies had now learned about the power of organised labour so they went on strike for increased wages - the first recorded strike in South Africa.

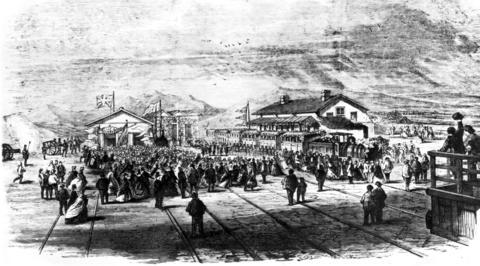

When things settled down Brounger made good progress and the first section of the line to Eerste River was ready in 1862, and the remaining distance to Wellington was completed in the following year, when the engines and rolling stock were ready for the grand opening in November. As usual this was a sumptuous occasion and the Governor, by now Sir Philip Wodehouse, and 400 guests joined the train and rode out in a luxurious state coach to the luncheon at the terminus. The company certainly did them proud - they even paid Thomas Bowler £10 to paint two watercolours of the event which were duly reproduced in the Illustrated London News.

Thomas Bowler (Wikipedia)

Opening of Cape Town Wellington line (Thomas Bowler painting - DRISA Archive)

Brounger, his work completed, went back to England where he became immersed in local railway development, and the Cape Government wondered what to do next.

Click here to read Part II - Forward into the Interior.

Main image: Turning of the first sod of the Wellington Railway by Sir G Grey. Reproduction from the Illustrated London News. (DRISA Archive)

Tony Murray is a retired civil engineer who has developed an interest in local engineering history. He spent most of his career with the Divisional Council of the Cape and its successors, and ended in charge of the Engineering Department of the Cape Metropolitan Council. He has written extensively on various aspects of his profession, and became the first chairman of the History and Heritage Panel of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering. Among other achievements he was responsible for persuading the American Society of Civil Engineers to award International Engineering Heritage Landmark status to the Woodhead dam on Table Mountain and the Lighthouse at Cape Agulhas. After serving for 10 years on SAICE Executive Board, in 2010 he received the rare honour of being made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution. Tony has written manuals, prepared lectures and developed extensive PowerPoint presentations on ways in which the relationship between municipal councillors and engineers can be more effective, and he has presented the course around the country. He has been a popular lecturer at UCT Summer School and has presented five series of talks about engineers and their achievements. He was President of the Owl Club in 2011. His book "Ninham Shand – the Man, the Practice", the story of the well-known consulting engineer and the company he founded, was published in 2010. In 2015 “Megastructures and Masterminds”, stories of some South African civil engineers and their achievements was written for the general public and appeared on the shelves of good bookstores. “Past Masters” a collection of his articles about 19th century South African Engineers is also available from the SAICE Bookshop.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.