Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Certainties during most of human history were famine, death and pestilence and war, as per the ‘four horsemen of the Apocalypse’. We have the Pestilence ‘horseman’ galloping across the world right now, as in the Covid-19 pandemic. During this pandemic we contemplate our exposure to this ‘pestilence’ with a certain raw, ancient fear. We are waiting for the vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 virus (Covid-19) with some anxiety, hoping that this disease can be brought to an end. That our global society should experience such an old-fashioned inconvenience goes against our culture of ‘having it all, now’ and the belief in the wonders of the modern world.

A section of Albrecht Dürer's 1497 famous wood cut from his Apocalypse series

In the 1960s, medical science announced that they had conquered disease. Infectious human diseases were to be a thing of the past because of the antibiotics being developed. The bad news is that we have not conquered infectious disease at all: bacteria are evolving to be resistant to antibiotics, especially those bacteria to be found in hospital or livestock environments. Even viruses have upped their game, ever mutating. My microbiology textbook dated 1980 devoted about 300 words to a small insignificant group of viruses, the coronaviruses which caused the common cold. Now scientists could write a whole text book about one coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. We are always fearfully waiting for the next ‘big one’ and we got a sophisticated upgrade of the old coronavirus in the form of Covid-19 and a pandemic.

The good news is that vast progress has been made: the smallpox virus is now extinct; the polio virus is under control with vaccines. Ebola (another virus) outbreaks in Africa are [mostly] controlled by surveillance, education and behavioural change. Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) can manage their disease with anti-retroviral drugs. And antibiotics have literally saved hundreds of millions of lives that would have otherwise succumbed to infection.

Diseases of the skin circa 1927

An old medical textbook I found in a second hand shop offers a window on the recent past when the medical world struggled to deal with infectious diseases (in this case, of the skin). The 1927 ‘Diseases of the Skin’ by James H. Sequeira M.D. Lond., F.R.C.P. Lond. and F.R.C.S. Eng. and published in London, really does give one something to think about! Back then, there were many nasty untreatable conditions with fulminating, infectious, ulcerating and spreading lesions which destroyed nasal cartilages, caused gaping, oozing sores on the legs or led to purple tumours on the neck, and which could be untreatable for up to 30 years (and then the patient died). That poor young man with lupus mutilans who lost most of the fingers of his hands! The sad child with tuberculous pseudo-elephantiasis of the leg, and that pretty lady with an epithelioma (skin cancer) on top of lupus vulgaris who suffered this condition for 23 years! Lupus diseases are various types of chronic and progressive form of tuberculosis affecting the skin, mucous membranes and lymph glands, but thankfully are now rare.

The outcomes of disease were also much worse in the past because treatments were so rudimentary or even toxic. In many cases, doctors had little idea of what caused the ailments and some of the treatments themselves had horrific side effects. Using X-rays to treat ringworm of the scalp often resulted in severe radiation burns. Syphilis, essentially also a skin disease, was treated with compounds of arsenic, bismuth, mercury and iodides in the 1920s. The disease is now treated effectively with antibiotics: unfortunately Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis, has evolved antibiotic resistance, meaning that it is making a come-back.

While many of the horrible medical skin conditions described in the book, like impetigo, psoriasis, pellagra, eczema, scabies, ringworm and acne, are still around, antibiotics and other pharmaceutical treatments have made a vast difference to the outcomes of these conditions. Before modern treatments, many of these simple conditions became chronic, with persons suffering pain, disfigurement and stigma for decades.

Alarmingly, many photographs in the Sequeira 1927 book show medical professionals touching persons suffering from very infectious diseases with their bare hands. Perhaps disposable surgical gloves were not yet available. I almost did not want to touch Sequeira’s 94 year-old book in case there is some horrible pathogen still lurking on the paper, left behind by a doctor who paged hopefully through the book while prodding a patient with ulcerating dermal leishmaniasis.

The sickening names of ‘forgotten’ skin ailments

Many of the skin ailments described in the 1927 Sequeira book have complicated and frightening names for very messy and repulsive conditions. I was curious to see if these names still apply, or are the names now discredited and old-fashioned ‘Victorian’ medical terms. The names do still apply, and the diseases are still around although we understand their etiology and treatment better.

In keratodermia blenorrhabica (something linked to arthritis), lesions joined together to ‘form large crusty plaques with desquaminating edges’. Desquaminating means that the skin is peeling off. Gummatous ulceration of the nose is essentially a horrid condition caused by a long-standing syphilitic infection. Basically your nose rots away. The gumma are soft, granulomatous, tumour-like masses appearing during the late stages of syphilis and that occur beneath the skin, but also in the bones, nervous system and other organs and tissues. When your bones are affected, it is very painful. You don’t die but you wish you could. . Scrofuloderma is a skin and lymph node condition caused by a secondary tuberculosis infection, and symptoms include a bleak range of huge purple tubercular abscesses and ulcerations in children and young adults, usually around the neck. The abscesses may go on to form an ulcer with overhanging irregular bluish edges and inside the ulcer are ‘pale flabby granulations’. The scrofuloderma lesions are truly horrible, and this disease is definitely still around but can be successfully treated. In 1927, there was no effective treatment, other than the surgical removal of the abscesses. I am not going to show any of the photographs.

Dermatitis gangrenosa sounds horrible, a massive eruption of gangrenous lesions in children, sometimes linked to chicken pox, but fortunately is rare and not lethal, and does not result in scarring.

Diseases of the poor and indigent

The Sequeria (1927) book often states that some of the skin conditions occur amongst the ‘less well-to-do’ and the ‘poorer classes’ (his work was in London) as though these persons chose to have scabies burrowing into the palms of their hands or eczematoid ringworm colonising their groins. The prevalence of lupus vulgaris, a common Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) skin infection, is described as ‘although not confined to the poorer classes, is much more common in the children of the indigent and ill-fed than those in better surrounds” and “dirt, bad hygiene and insufficient food have an important influence on the resistance of the individual to infection” (Sequeria 1927), which may well be true.

We now know much more about the social determinants of disease, and yes, living in appalling conditions with hardly anything nourishing to eat, or doing dangerous work in a toxic environment, does result in a person contracting some very ugly and painful health conditions. Originally regarded as only slightly important, the social determinants of disease are now acknowledged as fundamental causes of health afflictions. The social determinants of health include issues of housing, access to water and sanitation, food and nutritional security, social equity and justice, and education. The globalised economy has a huge impact on human health, for example, the true cost of human migration is poor health. As we now know, fixing some of these social determinants of health is not a simple matter. A treatment of tablets won’t create ‘better surroundings’ or cure poverty.

Skin ailments caused by work situations, circa 1927

While many skin diseases are still with us, many skin afflictions relating to manufacturing occupations have vanished. These ailments have disappeared because these types of occupations have vanished, or manufacturing processes have changed. Dermatitis, an irritation of the skin, was caused by exposure to toxic chemicals used in many manufacturing processes. Direct contact with toxic chemical irritants such as chrome compounds, arsenic, coal tar, strong acids and alkalis also caused skin damage, especially to the hands. All these skin ailments must have been thoroughly unpleasant and caused great hardship and suffering.

The use of aniline and other dyes for dying leather clothing was a common cause of dermatitis, as were the dyes used for dying furs. Furriers and tailors engaged in making up fur garments or garments with fur trims also suffered from acute dermatitis on their hands, neck and face. Cheap clothing, cheap boots, belts and hatbands made of leather dyed with toxic dyes also produced dermatitis in susceptible persons, as did cheap face powders and hair dyes (this all in 1927). Also, persons handling hides and skins were liable to become infected with anthrax.

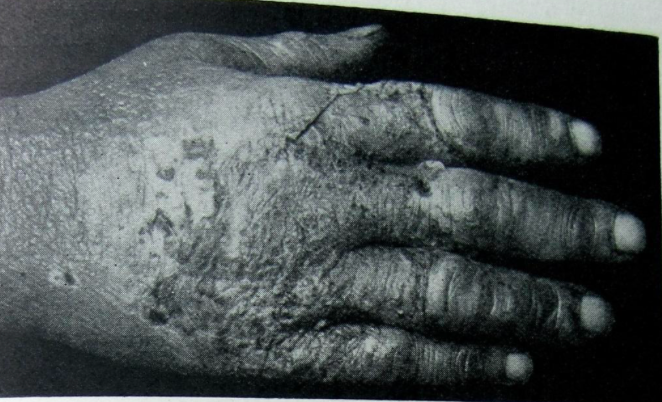

Hand of a French polisher (Sequeira 1927)

This photograph shows the hand of a French polisher who was required to use dichromate of potassium (potassium dichromate) and similar salts to polish furniture, causing these lesions (Sequeira 1927). The process of French polishing was very labour-intensive as well as hazardous, with layers of varnish being polished into the surface of high quality woods. Many manufacturers began to abandon the labour-intensive methods around 1930, preferring the cheaper and quicker (hopefully safer) techniques of spray finishing with nitrocellulose lacquer and abrasive buffing (Wikipedia). We also now know that potassium dichromate is a carcinogen in humans and can cause lung cancer.

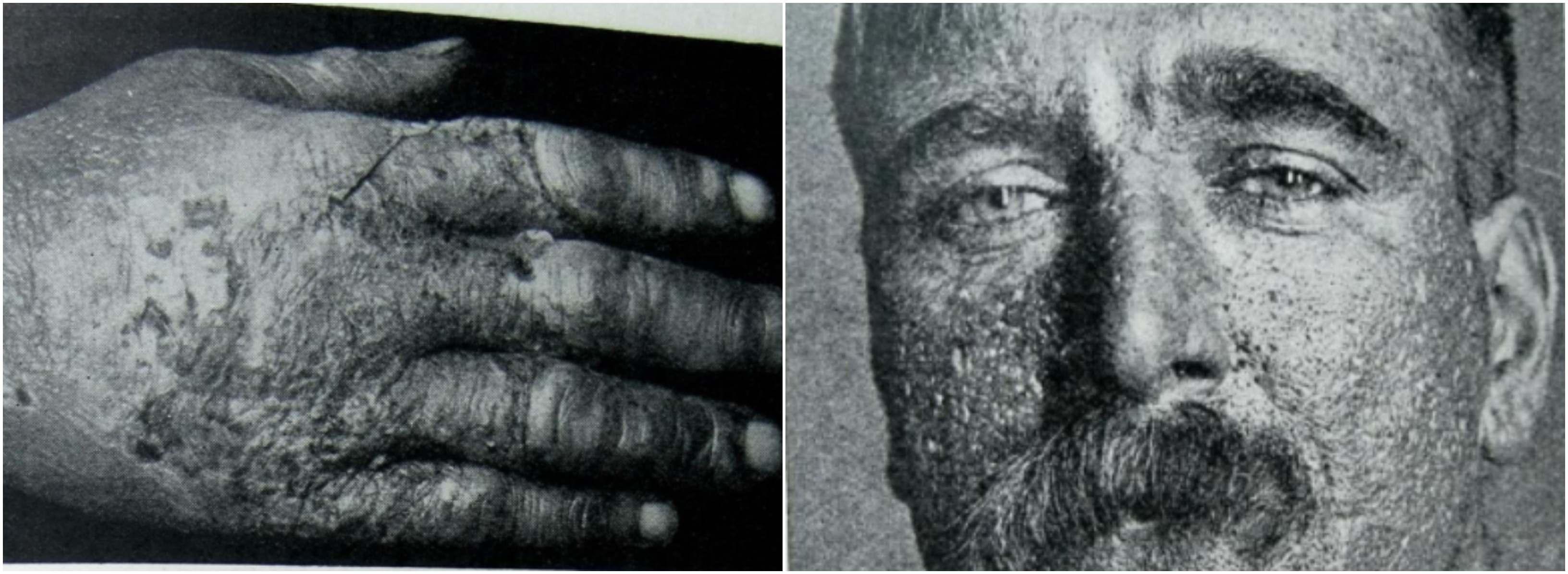

The image below is a photograph of hydrochloric acid dermatitis in a galvaniser (working with zinc electroplating), with exposure to this acid causing burns and severe ulceration (Sequeira 1927). The man’s hands look almost pickled and must have been very painful.

Hand of a galvaniser (Sequeira 1927)

Occupational disease of the skin also resulted from processes that mechanically injured the skin such as injuries due to handling sand, silicates and other rough substances. Substances which softened the skin, such as water, alkalis, soap, soda, lime and ammonia and substances which remove the natural grease from the skin, like turpentine, benzene and other solvents, also caused horrendous skin lesions. Washer women and domestic workers as well as persons washing the dishes in restaurants and hotels suffered from using harsh soaps and soda, and from having their hands in contact with water for long periods of time and their skin would literally peel away.

This is 'water maceration' of the hand from washing crockery in a restaurant (Sequeira 1927)

Persons who worked with tar or creosote also developed an eczematous dermatitis and later their skin might thicken and produce watery growths which developed into papillomatous tumours, many of which would fall off, but in some susceptible persons, they would develop into epithelial cancer. Other persons working with certain woods, notably teak, rosewood and ebony, could develop dermatitis from the oils in the wood and in some cases the worker’s face would erupt in suppurating lesions and their upper air passages would also become acutely inflamed. Now we know that these workers should be wearing respirators or work in well-ventilated workshops.

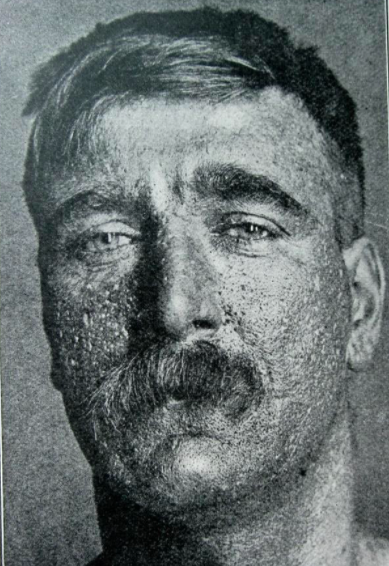

This man has tar acne, with the back and chest also affected. This condition resulted from workers who handled tar, pitch or creosote, for example those who sprayed roads with tar or are involved in creosoting wooden poles (Sequeira 1927).

The beginnings of occupational health and safety

Sequeira’s book ‘Diseases of the Skin’ (1927) thankfully does suggest that washing facilities must always be available in the work place, and that unskilled workers must be shown how to protect themselves from chemicals in the work place before developing skin ailments. Workers must wear protective overalls and caps, and there must be exhaust ventilation provided to remove noxious fumes and dusts. Regular medical inspections must be enforced and susceptible individuals must be removed from hazardous tasks and put on other work. This is still not the case in many parts of the world.

About the author: Sue Jean Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and has worked in the agricultural sector doing crop biotechnology research. She recently spent five years at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, coordinating an African mountain science network funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). Her current research interest is in resilient cities in Africa and the value of trees, parks and public open spaces. She also collects weird old medical books. She is a Research Fellow at the QwaQwa Afromontane Research Unit, University of Free State (South Africa).

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.