Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

It is early March 1879 in Zululand. It is the end of the rainy season and it is bucketting down on a daily basis on those men stationed at Fort Clery near the German Lutheran church and settlement at Luneberg, tucked away in the north west quadrant of Zululand about 6 miles from the Transvaal border. It is hot, sticky and sweaty in the intervals between showers. Roads dissolve into glutinous rivers of mud and the men are wet though and shivering most of the time. Shelter is, at best, corrugated iron or thatched lean-tos. Clothing just rots off the men, increasing their misery.

The mosquitoes, roused to breeding frenzy in the stagnant pools, make their lives a misery. Men are dropping like flies with enteric and dysentery. Dragged off to the makeshift hospital, they don’t fare very much better than those men still capable of remaining on their feet.

It has been a while since a convoy of supplies has come through from Derby in the Transvaal, and the men are living on boiled beef and weevily biscuits. Ugly, oozing veldt sores caused by bad nutrition burn incessantly. A combination of prickly heat and lice makes the men scratch constantly, turning the sores into gaping wounds.

Night after night they stare out over the parapets into the inky blackness, supposedly alert to the possibility of a Zulu attack. They are aware of what awaits them if it happens; torn-off lips, bellies slit open, private parts hacked off, but they are numbed by the pelting thunderstorms, lit by occasional jagged flashes of lightning. Eyes strain in the darkness, on tenterhooks in case the Zulus, fresh from their victory at Isandlwana, decide to turn their attention to the north.

But one can only stay alert for so long under these conditions. They are starting to switch off. Bored, wet through most of the time, disease ridden and plagued by insects, all in all, it’s a sodding rotten miserable billet!

But there is good news. A whole bunch of wagon masters and teamsters from Derby have just dragged themselves into the fort. Sick to death of battling for mile after mile in the worst possible weather, they have had enough and have astoundingly abandoned the convoy that they were bringing into Luneberg. The wagons are marooned in the mud near Myer’s drift on the Ntombe river, just a few miles away.

Myer’s Drift on the Ntombe River

Major Charles Tucker, the commander of the fort, is livid. He immediately sends a company of 80th Foot, under Captain David Moriarty, down to the drift with orders to retrieve the wagons and bring them in. Having struggled for hours to cover the distance, Moriarty finds them strung out all over the place. Gathering them together, he finds that the Ntombe River has been steadily rising in flood behind him, cutting off his path back to Luneberg.

He does the best he can, and after some time has managed to get two wagons across the swollen river, the oxen pulling them almost drowning in the attempt, rearing panic stricken, horns slashing and eyes rolling as they go under the brown, muddy water for the umpteenth time. These two wagons are left under the command of Lieutenant Henry Harward, with Colour Sergeant Anthony Booth and 34 men.

On the north bank, 34 wagons still stand, mired in the mud, in a loose upside down “v” shaped laager, with its’ two “feet” anchored on the bank of the river. Brooding over the futile efforts of the soldiers stands a ring of surrounding mountains, the most notable being Tafelkop, said to be the refuge of the renegade Prince uMbelini. Starkly lit by the lightning, they resemble an enclosure used by Zulus to keep their animals safe at night. No wonder the Zulus call the valley “Ntombe”, the goat pen.

Coming out on an inspection, Major Tucker has grave misgivings about Moriarty’s defences. He sees, however, that the men are dead beat, and Luneberg is only 6 miles away. He makes no move to order the wagons drawn up more tightly and shackled together. After all, they haven’t seen a Zulu for days. But they are under constant surveillance. Zulu scouts have dogged them for a while, waiting for an opportune moment to attack.

At 5 o’clock on the morning of 12 March 1879, the inevitable happens. The river, unnoticed by the sentries, has subsided during the night, now leaving a 20 yard gap between where the legs of the “v” shaped laager end and the muddy waters of the river now begin.

As the early morning mist lifts, shadowy figures slip through the gap and in an instant all is pandemonium inside the laager. Stabbing spears thunk home as exhausted soldiers stumble out from underneath their sodden blankets. Terrified screams rend the air. A few make a stubborn resistance, but it is quickly over. The reek of freshly spilt blood taints the fresh morning air.

And then it was time for the serious business of trophy taking, looting, plundering and destruction of whatever stores remained or were unable to be carried away.

Harward’s party on the south bank gave what covering fire they could, but very few of the soldiers or colonials knew how to swim and the river took its own toll of struggling men.

Harward ordered the retirement, then sped off on his horse to alert the garrison at Luneberg. Colour Sergeant Booth, men well in hand, kept up a concentrated fire while slowly retiring after Hayward. His actions that day saved his men and would earn him a Victoria Cross, while his officer would be court martialled for cowardice.

As Major Tucker later described it, as the relieving column approached the battle site:

A fearful and horrid site presented itself, and the stillness of the spot was awful. There were our men lying all about the place, some naked and some only half clad. All the bodies were full of assegai wounds and nearly all were disemboweled.

Nearly everything had been broken or torn into pieces, the tents being in shreds and the boxes broken in atoms, the mealies and flour thrown all about the place. They had killed all the dogs save one...

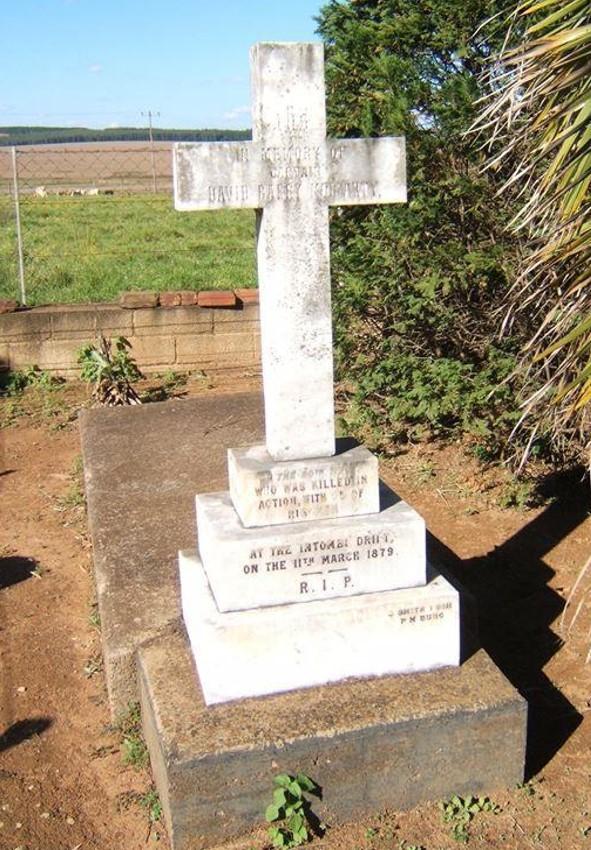

We found (Moriarty) lying on his face, inside the laager, quite naked... we brought into Luneberg the bodies of (Moriarty) and Dr. Cobbin, who was also killed there, and they were buried the following day.

We... dug an enormous trench in which to bury them (the soldiers); this took us nearly all day. About 5 p.m. I read the burial service over the dead. We fired three volleys and then returned to camp with what little the Zulus had left in the wagons.

Moriarty grave at Luneberg

The total losses were 61 soldiers and 18 civilians killed. The names of the 80th’s casualties are now inscribed on imitation Zulu shields at Lichfield Cathedral.

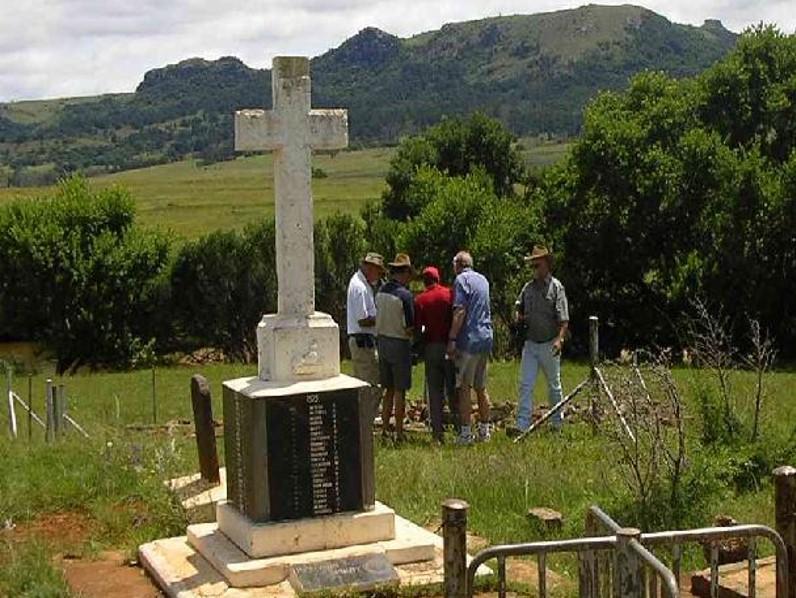

A couple of days prior to the re-enactment commemorating the 125th anniversary of the battle of Isandlwana, I had the privilege of guiding four members of the 80th Regiment of Foot Staffordshire Volunteers living history group to Ntombe.

Ntombe Drift

Still somewhat decimated from that incident, they appear to have only recruited these 4 men since 1879. But the regiment lives on! Just!

Jim Buckle, Pete Webb, Phil Joynson and Pete Wooldrige had come out to pay homage to their forebears. As is normal during our rainy season, it usually fails to rain when it is expected to. However, grab a bunch of Pom tourists, slap on the suntan lotion and get out the cricket gear, and it iss guaranteed to come down in buckets!

And so it was on the day. Misty, cold, with intermittent squalls once again turning the red clay soil into glue. Our doughty warriors, though, were made of sterner stuff and piled out of the cars, dressed in appropriate gear and went off to inspect the monument. First erected by the South Staffordshires in 1921 it is now sadly in dire need of repair, especially the fences surrounding it, which have gone no doubt to assist in an informal local housing project.

The elements notwithstanding, the visit was an emotional one, albeit looked at with great amusement by the local Zulu schoolchildren who were breaking up for the day. Mad dogs and Englishmen...

Then on to Luneburg to the immaculately kept German cemetery to view Surgeon Cobbin’s and Captain Moriarty’s gravestones. Phil got himself covered in mud, but vowed never to wash his uniform again as it was, as he so rightly explained, “Ntombe mud”.

The lads have decided to attempt to raise funds to resurrect the monument and its fencing and to spruce up the area in general.

In such a remote area, so far, far away from most civilised trappings, that would indeed be a fitting tribute to those who died so terribly so long ago. Sadly, various restoration projects over the subsequent years have failed. The monument is still intact, but the fences are, once again, long gone.

Main image: Memorial at Entombe Drift.

About the author: Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.