Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

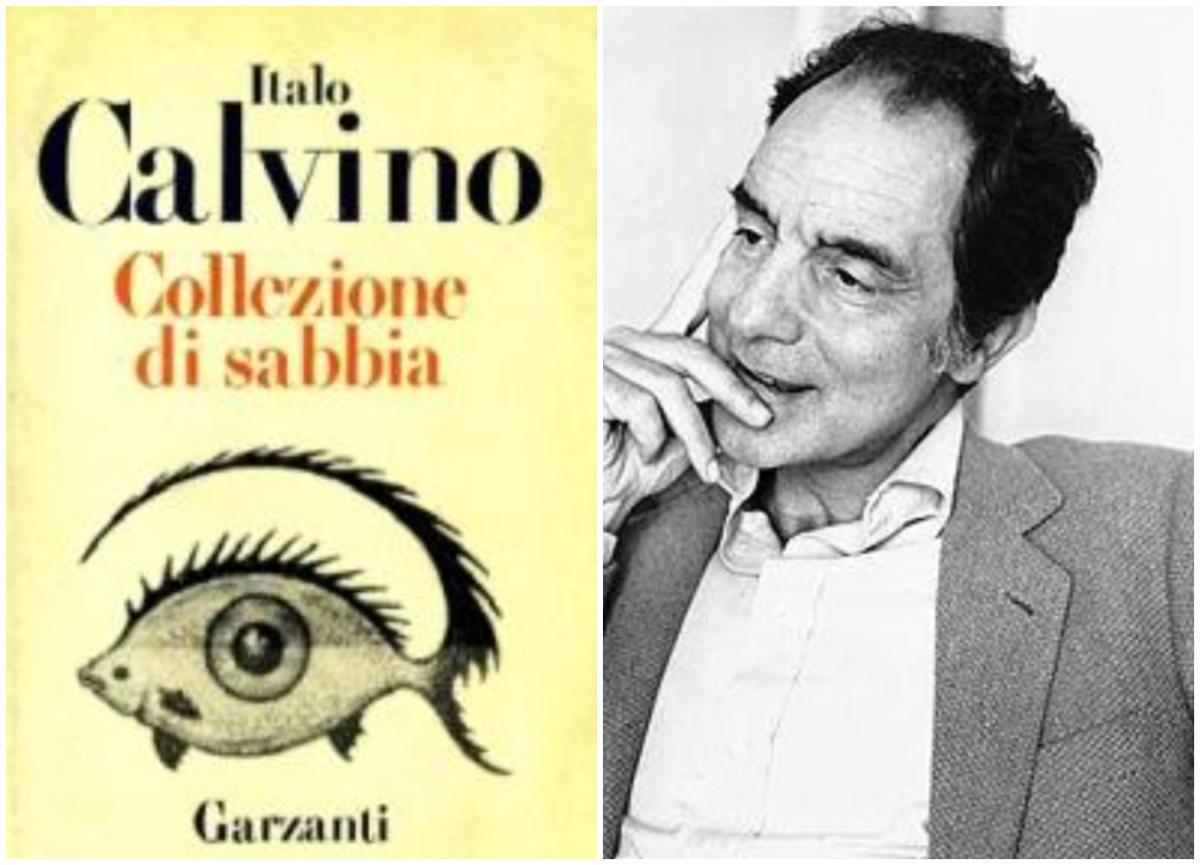

Shortly before his death in 1984, Italo Calvino assembled thirty-eight essays in his Collections of Sand (Collezione di Sabbia). One section of essays was labelled ‘The Traveller in the Map’ (Il viandante nella mappa). Calvino described his notion of a cartographic odyssey:

The simplest form of a map isn’t the one we consider the most natural today: that is the map which represents the surface of the Earth as seen by an extra-terrestrial eye. The first need, to put places on a map, is connected with travel: a map is the reminder of ... the tracing of a route.

Understanding an image through time and space is essential in cartography. Time assumes a past story.

While a map’s borders neatly constrain the geography of the map, they can also constrain one’s interpretation of the map. To get to Calvino’s notion of a cartographic odyssey, the gaze of the beholder of the map must wander beyond the restrictions imposed by the map border and page margins.

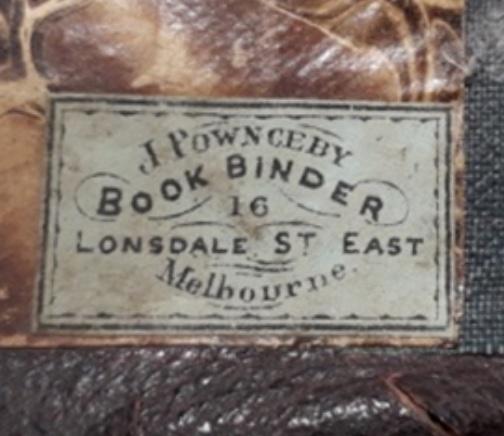

For some time, I had been mulling over the destiny of a distressed, incomplete Atlas that was published in 1825, in London. The author of the maps was James Wyld the Younger, geographer to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. I was perplexed by the small label inside the atlas: ‘J Pownceby, Book Binder, Lonsdale St East, Melbourne’. A London publication bound in Australia?

A perplexing label

I homed in on a couple of rogue maps, published before 1825, that had been bound in the atlas together with Wyld’s maps.

On one there was a handwritten annotation adjacent to lines that showed the course of a ship between the Cape Verde Islands: ‘the track of The Fanny of London, bound with colonists to Cape of Good Hope, March 1820.’

But the binder of the atlas was in Australia!?

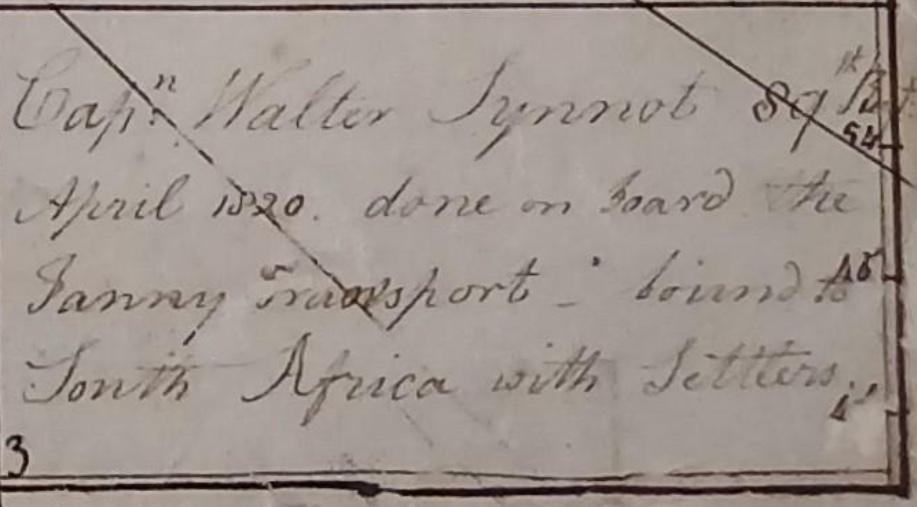

The author of the annotation identified himself at the bottom right of the page. The author and, presumably, the traveller in the map was ‘Capn Walter Synnot 39th Regiment, April 1820 – done aboard The Fanny transport bound for South Africa with Settlers.’

The bottom right of the page

So, this atlas had been published by James Wyld in 1825 in London and re-bound, in Melbourne, Australia with additional pages included in the re-binding. But the annotation was about a voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, not Australia. What was going on?

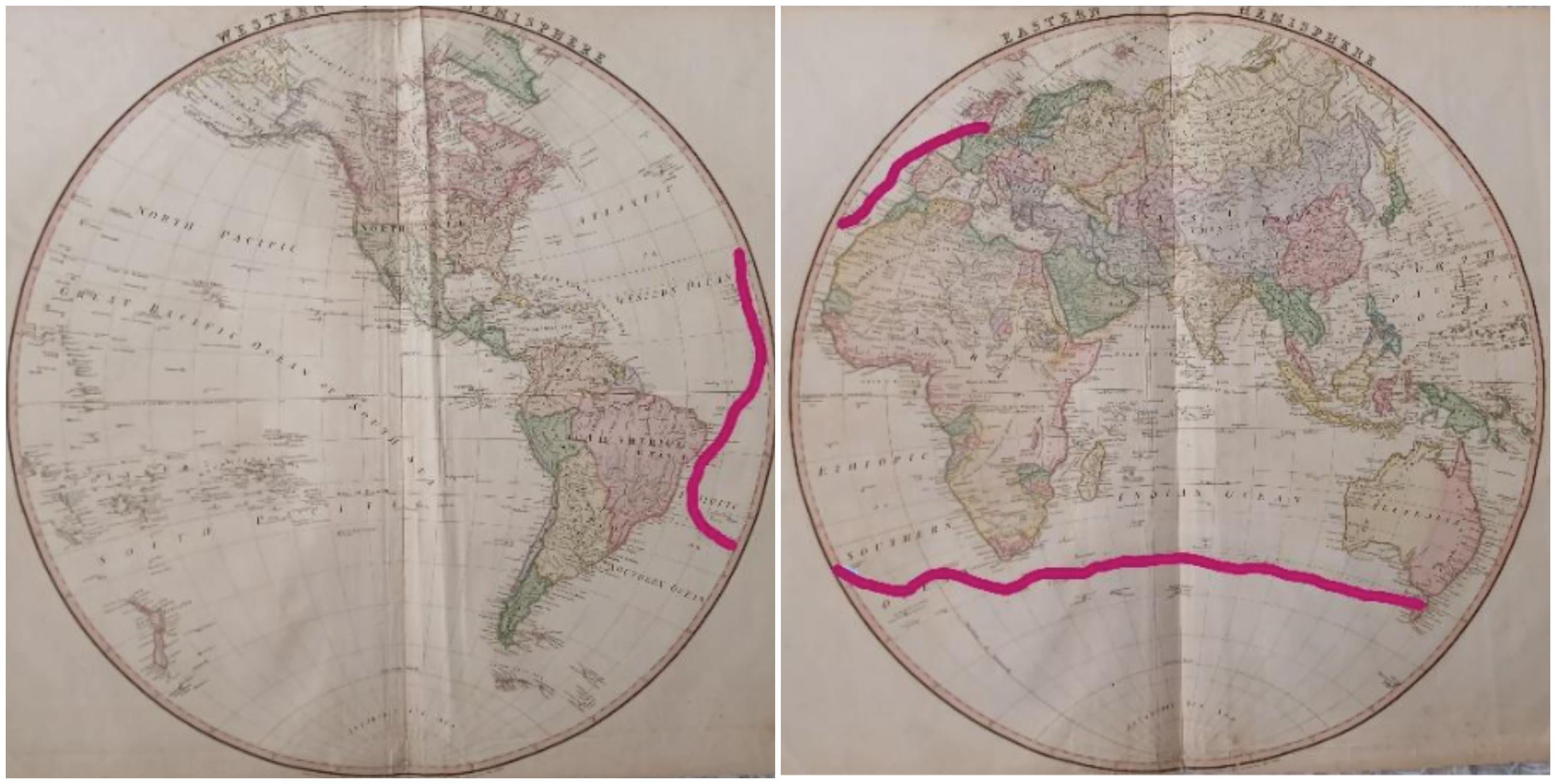

I paged through the atlas in the hope of further clues. With my interest now focused on understanding the Australia connection, I saw something I had not seen before. Someone, perhaps Synnot, had drawn in pencil, on the maps of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres, a faint line interrupted by a series of more than a hundred dots. I grabbed my magnifier and traced the line to its origin. The line started in the Eastern Hemisphere, in the Thames River, passed the Canary Islands and then headed south-west towards the coast of Brazil in the Western Hemisphere. Then the line headed southeast and crossed back to the Eastern Hemisphere to the 40° South, the Roaring Forties.

Walter Synnott plotted the 1836, non-stop route (highlighted) of the Amelia Thompson in on James Wyld’s 1825 maps of the Western and Eastern Hemisphere

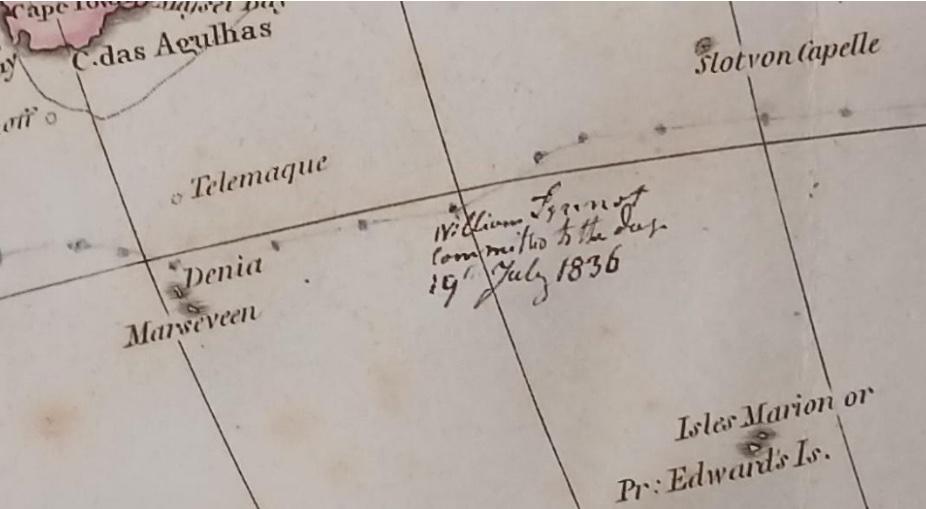

The spaces between the dots decreased when the hip crossed the doldrums and increased as the ship entered the trade wind. So, the dots must have been daily locations of a ship. The dotted line bypassed the Cape of Good Hope. It continued a tad north of Marion Island, above which there was poignant handwritten entry: ‘William Synnot committed to the deep, 19th July 1836’. Surely William was related to the Synnot who had been en route to The Cape in 1820?

The handwritten entry

The line continued eastwards in the Indian Ocean at 40°S, a route that allowed the ship to travel swiftly in the favourable winds that would reduce travelling time. The line passed the tiny islands of St. Paul and Amsterdam, on the sighting of which ships headed for the spice islands would turn north (the Brouwer Route). But the ‘Synnot line’ ended at Van Dieman's Land (i.e. Tasmania). There was another handwritten entry where the line passed islands in the southern Indian Ocean: ‘Voyage to Van Dieman’s Land in four months and (?) 2 days’ – I am still not sure of the symbol before the ‘2’.

I speculated that the Synnots must have had access to preserved citrus juice while on that 2-month non-stop voyage; otherwise, scurvy would have been inevitable after six weeks and they would have been very ill when they reached Tasmania.

Now I had a superficial understanding of the traveller in the map. In 1820 Walter Synnot was a settler on a transporter (The Fanny) bound for the Cape of Good Hope. In 1836 William Synnot, presumably a relative of Walter, died aboard an unnamed ship en route to Tasmania. Furthermore, on some unknown date, Wyld’s World Atlas was rebound in Melbourne, Australia, presumably in order to include pages with entries that recorded the voyages to The Cape and to Van Dieman's Land. So, I concluded, Walter Synnot must have returned to Ireland and settled in Australia in 1836. Now to connect the dots in his biography.

Walter Synnot’s Odyssey

I continued my investigation into the life of the traveller in the map. Here is a synopsis of what I learned:

Walter Synnot (1773 – 1851) was a son of Sir Walter Synnot, from Ballymoyer House, who was sheriff of Wexford, Ireland. Walter Snr. was prominent in the linen trade and lead mining. After a spell in active army service, Walter Jnr. settled in the Cape of Good Hope in 1820, returned to Ireland in 1825 and then, in 1836, he emigrated again, with an enlarged family, but now to Van Diemen’s Land. He farmed there then moved into the town of Launceston until his death.

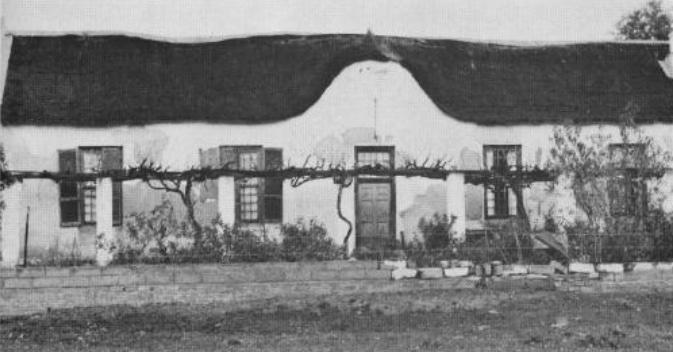

Ballmoyer House

Military Service, to half pay and emigration

In 1783, Walter Synnot Jnr joined the 66th Regiment (Berkshire) as an ensign and in 1797 was promoted to captain of the 39th Regiment. Walter seems to have painted and sketched as he travelled with the regiment, even under the most trying of circumstances of a sinking ship!

In the early 1800s, Walter went on half pay and settled on the family estate with his wife. After she died, he married again. In May 1818, the restless Synnot enquired about the possibility of emigrating from Ireland to the Cape. He followed through in 1819, when parliament announced an official emigration scheme to the Cape of Good Hope (now a British colony). The would-be Irish emigrant applied to lead a party of 28 people.

Synnot's own family group comprised his 12-year-old son by his first marriage, his second wife and their two small sons (a third son was born during the voyage); Mrs Synnot’s sister (or perhaps a niece) was also in the party.

Synnot’s emigration goals were ‘a desire of promoting civilization amongst the surrounding savage tribes and providing for my children a permanent subsistence.’

Cape of Good Hope

Soon after Christmas 1819, twenty-one ships transporting 4,000 settlers were on their way from England to the Cape: the 1820 settlers. On 12 February 1820, four Irish settler parties sailed from the Cove of Cork aboard the transporters Fanny and the East Indian. Three months later they anchored in Simon's Bay, the winter anchorage at the Cape of Good Hope.

Apparently, it was official policy that the Irish settlers should be located separately from the main body of emigrants who had been sent to Albany. This was astonishing news to the Irish who were disappointed and very unhappy. Nevertheless, in mid-May the transporters sailed on to Saldanha Bay on the West coast of southern Africa, about 150 km north of Cape Town. The Irish settlers disembarked and proceeded on wagon to the Groot Seekoei Vallei (Great Hippopotamus Valley) in the Clanwilliam district. Synnot was allocated a farm named De Vlei (The Marsh), at the confluence of the Jan Disselsriveir and the Olifants River.

However, the site proved unsuitable: poor grazing, insufficient water and a lack of suitable agricultural soil. On arrival in June 1820 a despairing Synnot wrote a letter to his brother Marcus: ‘if I had been aware of the circumstances of this place I would never have come here.’

The understandably disgruntled Irish settlers tried the patience of the Cape administration with their quarrelling and insults, but Captain Synnot was regarded with considerable favour: described by Sir Rufane Donkin, the Acting Governor of the Cape, as 'one of the most respectable of all the settlers’.

Mount Synnot near Clanwilliam is named after Walter, the Heemraad and farmer (Rev Francis McCleland: An Interlude in Clanwilliam 1820 - 1825 - The Casual Observer)

Synnot chose to remain in Clanwilliam when the Irish settlers subsequently were given the option of relocation in Albany. Soon after his arrival he was appointed a Special Heemraad (Justice of the Peace) for the district and in 1821 became Deputy Landdrost (Magistrate) of the Tulbagh district. He held this post until he returned to Ireland in 1825. He had settled on unsuitable vacant land in Clanwilliam but left a profitable farm with a farmhouse and a watermill, to which the townspeople brought their grain to be milled.

Walter Synnot's House (Rev Francis McCleland - An Interlude in Clanwilliam 1820 - 1825 - The Casual Observer)

Synnot returned to Ireland with a large collection of bulbs and seeds, some of which he sold in England and others he donated to the Royal Dublin Society. He also returned with paintings (see below).

Van Dieman’s Land

I have not found out, nor did I search for anything of Synnot’s life In Ireland after his return. But the 1830s were a difficult time in Ireland and, presumably, also for the Synnots. In 1836 Walter (then aged about 63), his third wife Mary Jane and eight of the children from his second marriage emigrated again, this time to Van Diemen’s Land. On 28 April 1836, they sailed from London on the Amelia Thompson, a barque with more than a hundred female emigrants, who had responded to advertised appeals for new settlers in Van Diemen’s Land and New Holland (Australia).

Synnot plotted the daily the position of the Amelia Thompson on the charts of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres in his copy of James Wyld’s World Atlas. Presumably Synnot had received information on the ship’s location from the navigator who would have used a sextant for determining latitude and a marine chronometer for longitude. In the 1830s the chronometer was accurate to with two seconds per day (only 0.62 kilometres at 40°S).

The Amelia Thompson

On the 18th of July 1836 he inscribed a poignant note on the chart: the date and location of burial at sea of his son William who had died during the voyage from an unknown cause. They arrived at Van Diemen’s Land on 25 August and Synnot noted, adjacent to the track on his chart, the duration of the voyage: four months and 2 days (non-stop) – maybe four months less 2 days. (It had taken three months to reach the Cape). The Synnots lived in the area about Launceston; Walter died in 1851 in the town.

Synnot’s Forgotten Botanical Art

My investigation into Walter Synnot took me to an unexpected destination: his beautiful paintings of Clanwilliam flora. This settler was a competent amateur botanist and botanical artist. The unique book of his paintings of flowers from Clanwilliam in the Cape of Good Hope is conserved, but languishes under-appreciated, in the special collection of the Baillieu Library of the University of Melbourne. It is virtually unknown to South African botanists, nor is Synnot recognised here for his botanical art.

According to Robert Sweet, the London nurseryman and botanist, Synnot sent more new and rare Cape bulbs to England than any other individual. Numerous plants from Synnot were featured in the second volume of Sweet’s The British flower garden. In recognition of Synnot’s contribution, Sweet named a genus of lily after him: Synnotia (initially, Sweet had misnamed it Synnetia).

Sweet frequently commented on the rarity of the plants Synnot had collected; some had been seen in London before ‘but had been lost to our collections for many years’. Others, such as the plant they named after him, Synnotia variegata, were ‘quite new to Europe’. Synnot noted on his painting of S. variegata that ‘This beautiful plant has no odour. It is rare in the vicinity of Clan William and only found on Butler’s Hill—opposite the Drostdy - in rich dry soil.’ The plant is confined almost exclusively to the Clanwilliam district and varies in colour.

Walter Synnot's painting of Synnotia variegata

I do not know of the eventual destiny of the seeds and bulbs Synnot took back to England and Ireland. However, he did leave a lasting legacy: Synnot painted 176 plants from the Clanwilliam district; these were bound in a volume that he left in England with his son Robert Walter may have hoped that the volume might get wider publicity. The book was never published but remains an exquisite manuscript record of a rather difficult period in the life of its creator. The book of paintings eventually followed family emigration to Australia, where it was donated by the Synnot family to the Library of the University of Melbourne.

‘The volume is folio size and contains 176 plates of watercolours, each of a flowering plant or shrub, some done to life size. The drawings follow a traditional botanical format, with the whole plant depicted from root to flower, sometimes with the soil line indicated when it is obviously unusual. The main painting is sometimes accompanied by smaller scientific drawings such as cross-sections through the stem or seed. Most plates have a heading indicating the plant’s Linnaean classification. The spine has an embossed label, ‘Cape Plants and Flowers’ above a faded ink version, ‘Cape Plants and Flowers By Capt. Walter Synnot’. On the inside front board of the book is Captain Synnot’s bookplate and notes regarding its history.’ (Dorothea Rowse)

Conclusion

Walter Synnot was the unexpected ‘traveller in the map’ that had been included in a rebound example of an 1825 atlas by James Wyld. The cartographic record of these stories is an unusual, possibly unique depiction of the route, the speed of travel and the risk of death during the long voyage. However, the record is also the portal to narratives off the map: the unusual story of the Irish 1820 settlers to the Cape Colony; the route in 1836 of the Amelia Thompson to Tasmania; and the voluntary emigration to Australia of single women and families, including the Synnot family. Walter Synnot’s book of 176 exquisite paintings of flowering plants of Clanwilliam (1820-1825) is now conserved in a Melbourne library, an almost unknown contribution to South Africa’s heritage of botany and botanical art.

Roger practiced medicine, was associate professor of human physiology, and has been an executive and director of businesses locally and abroad. He has also collected historical maps of South Africa and the continent of Africa; these maps are now conserved at the University of South Africa and Stanford University, USA. His articles on the maps and Cape history have been published in international journals and local periodicals.

Selected reading and sources

- Dorothea Rowse Captain Walter Synnot and his book of Cape plants and flowers. University of Melbourne Collections, Issue 8, June 2011: 26 -31.

- Biographical Database of Southern African Science, Synnot, Capt Walter John (plant collection)

- Graham Dickason. Irish settlers to the Cape. A history of the Clanwilliam 1820 Settlers from Cork harbour. Cape Town, A. A. Balkema,1973.

- Roger Stewart. Treasure hunt. Veld and Flora. Dec 2020, pp. 26 – 29.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.