Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

When the popular board game, “Monopoly”, was introduced to Britain in 1935 by John Wadddington Ltd. of Leeds (Yorkshire), Marylebone (pronounced Mahr-le-buhn) was one of the four London railway termini chosen. The others were Fenchurch Street, Kings Cross and Liverpool Street. Those four stations just so happened to be owned by the same railway company, the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER), thus there was no room on the board for the main line stations of the other “Big Four” railway companies, namely Paddington (GWR), Euston (LMS) and Waterloo (Southern). Monopoly was not only a success in Britain, but also throughout the British Empire and the board game retained the street and station names of London, the capital city. Through playing “Monopoly”, many thousands of people across the globe became familiar with London’s place names and many a visitor would seek out a “Square” from the board game. I could well imagine the disappointment a visitor would have had on seeing Marylebone Station for the first time, as it was unpretentious and somewhat small, having only four platforms and its facade was said to look rather like a branch public library in a Manchester suburb.

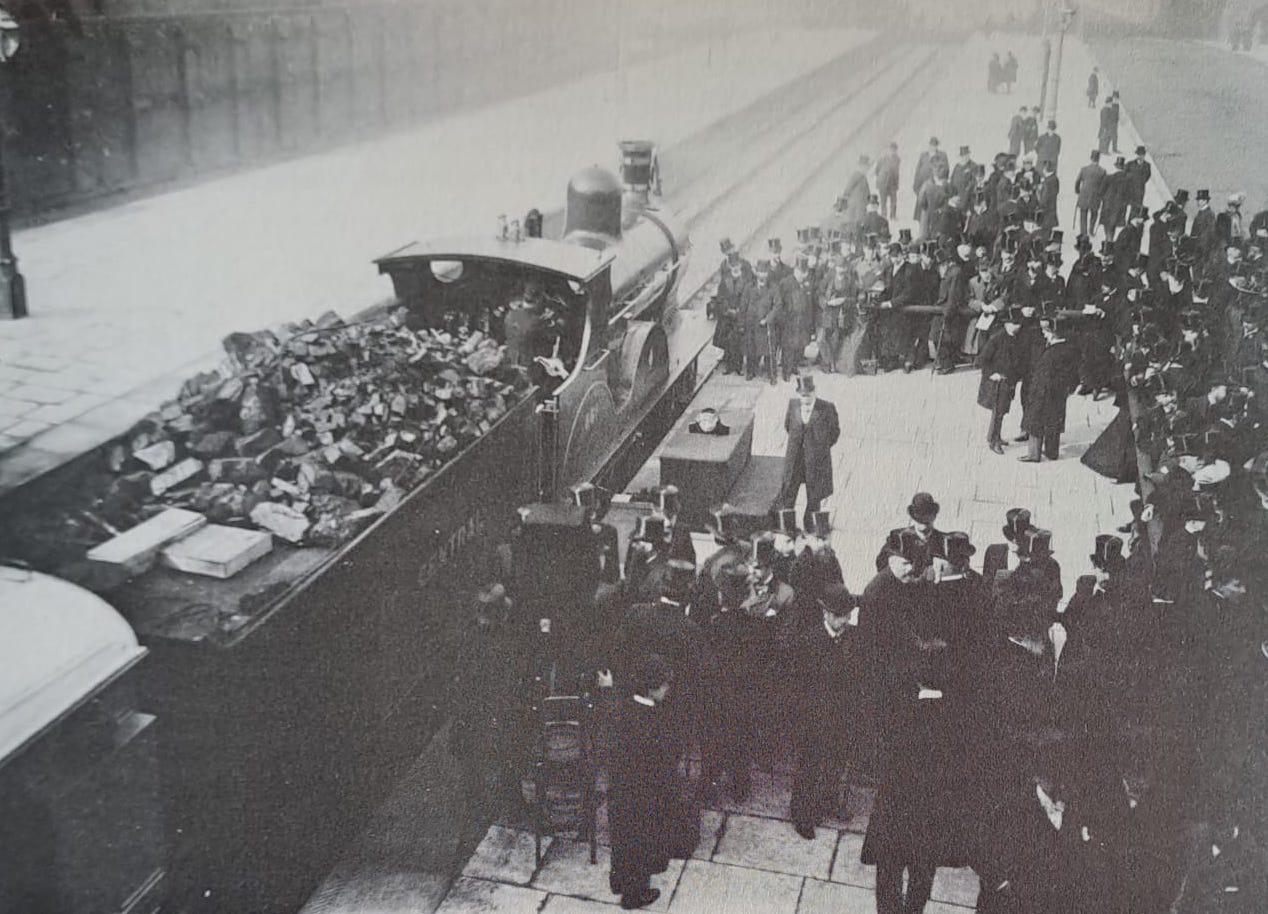

Marylebone was the last railway terminus to be opened in London, with its first “Down” passenger train leaving for Sheffield and Manchester, on the 15th March 1899. The station and the extensive goods yard were built to serve the Great Central Railway (GCR) at the southern end of the London Extension of the former Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR). In 1897 the MS&LR changed its title to the GCR, in order to reflect its new status as a Trunk Railway, however it would be true to say that the company never generated the passenger volumes that were anticipated by those who promoted the railway and it was said that MS&L stood for “Money Sunk & Lost” and that GC stood for “Gone Completely”.

First Train out of Marylebone (Leicester Museums)

Promoting the Line

The “Cinderella”of London’s termini, would be a good epithet for Marylebone, as it always played “second fiddle” to its more illustrious neighbours along the Euston Road; namely, Euston, St. Pancras and Kings Cross, but like “Cinders” it would triumph in the end, although it would take nearly 100 years. Perhaps “Sleeping Beauty” would be a more apt portrayal.

For the whole duration of the 20th Century Marylebone was under utilised by a succession of operators; the GCR (1899-1922), the LNER (1923-1947) and British Railways (BR: 1948-1996), but since privatisation (as of 21st July 1996) it has become highly successful under the banner of “Chiltern Railways”. The reason for the spectacular change of fortune for a railway station that was served a closure notice in 1984 is plain and simple, there was an upsurge of commuters travelling the “Chiltern Line” into London from the towns outside of the Green Belt, namely Aylesbury, Banbury, Beaconsfield, Bicester, Gerrards Cross, High Wycombe and Princes Risborough.

If truth be told, it was the establishment of the pre-privatisation BR brand “Network South East” (NSE), in 1986, that was instrumental in saving Marylebone and its commuter services along the Chiltern Line. When NSE was instigated it had a two-fold aim, the first being to improve the weekly peak hour commuter operations in the Home Counties around London and the second was to attract more passengers to travel by train out of the rush hours. The Chiltern Line, in particular, was seen to be in drastic need of improvement, as everything – the tracks, trains, signalling and stations were all in a run-down state, mainly due to the uncertainty of the future of the line. Renewal or Total Route Modernisation, in the jargon of the time, meant a thorough refit of the line, with no quick fix or half measures taken.

At this point it is worthwhile backtracking to give some historical context into why Marylebone and the Chiltern line exist in the first place. They exist owing to one man’s ambition, that man being a Victorian visionary from the same mould as Cecil Rhodes, a man who got things done and his name was Edward Watkin (1819-1901), whose lifespan replicated that of Queen Victoria’s own.

Portrait of Sir Edward Watkin

Watkin was the sometime Chairman of the MS&LR, the Metropolitan Railway, the South Eastern Railway, the East London Railway and the Submarine Continental Railway Co. (the progenitor of the Channel Tunnel Co.) and his dream was to travel along those companies’ lines and through a Channel Tunnel and so on to Paris. He once said “If this line is made, it will make the Metropolitan and South Eastern parts of a through system running right through the country – a sort of backbone for the commerce and industry of this country”. Alas it was not to be as the British government stopped all work on the Channel Tunnel, on the grounds that if it were built an invading army could march through it!

Edward Watkin was a Railway King and the jewel in his crown was the MS&LR, which under his leadership expanded from a second tier northern provincial railway to become a main line from the North to London. When he retired, in 1894 (at the age of 75), from the Chair of the MSLR, “The Economist” remarked “His retirement will deprive the business world of much that is interesting, the gain being however, the accession of a larger measure of peace”. He was a mover and shaker and ruled his railway kingdom as an absolute monarch.

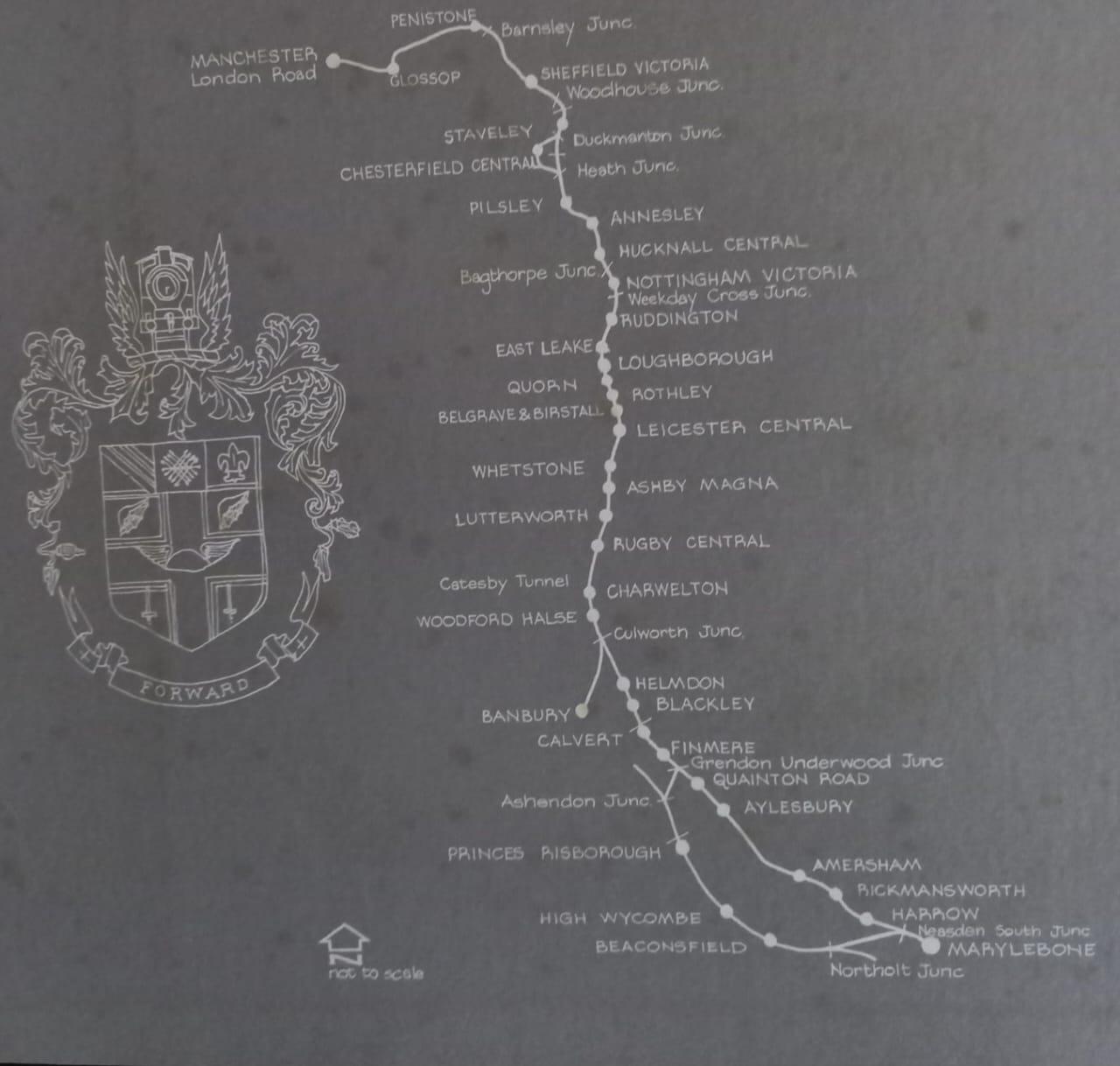

The London Extension of the MS&LR, that became the GCR (on 1st August 1897), ran from Annesley Junction (just north of Nottingham), southwards to Quainton Road (just north of Aylesbury, where it made a connection with the Metropolitan Railway, the “Up” GCR expresses would then run on the rails of the MET until Canfield Place (near Finchley Road) was reached and then diverge onto a two mile long spur running through two tunnels, the Hampstead Tunnel and the St. John’s Wood Tunnel (which went under Lord’s Cricket Ground), to terminate at Marylebone Station.

With Edward Watkin no longer at the helm of the GCR and the MET, relations at Board level, deteriorated to a low ebb, which finally came to a head, when on the evening of 30th July 1898, John Bell, the Chairman of MET, ordered the stopping of a GCR coal train from running onto Metropolitan metals at Quainton Road. The net result of this action was for the GCR to seek another route into the Capital. An alternative route was achieved by enlisting the aid of the Great Western Railway and it would be a case of “killing two birds with one stone”, as the GCR desired a second line into Marylebone and the GWR, known derisively, as the Great Way Round” by travellers, needed a “Cut-off” line to Birmingham, which would save 18 miles (and 20 minutes) on their existing route from Paddington to Birmingham Snow Hill via Reading, Didcot and Oxford. It was a “Win Win”, if ever there was, for both companies.

The Great Western & Great Central Joint Railway (GW&GCJR) would run between Northolt Junction (west London) and Ashendon Junction (west of Aylesbury) and it would passage partially through the Chiltern Hills for a distance of 34 miles, hence the title of the current operator, “Chiltern Railways”. At either end of the Joint Railway the individual companies made their own connections to their existing systems.

Cutting through the chalk of the Chilterns (SWA Newton)

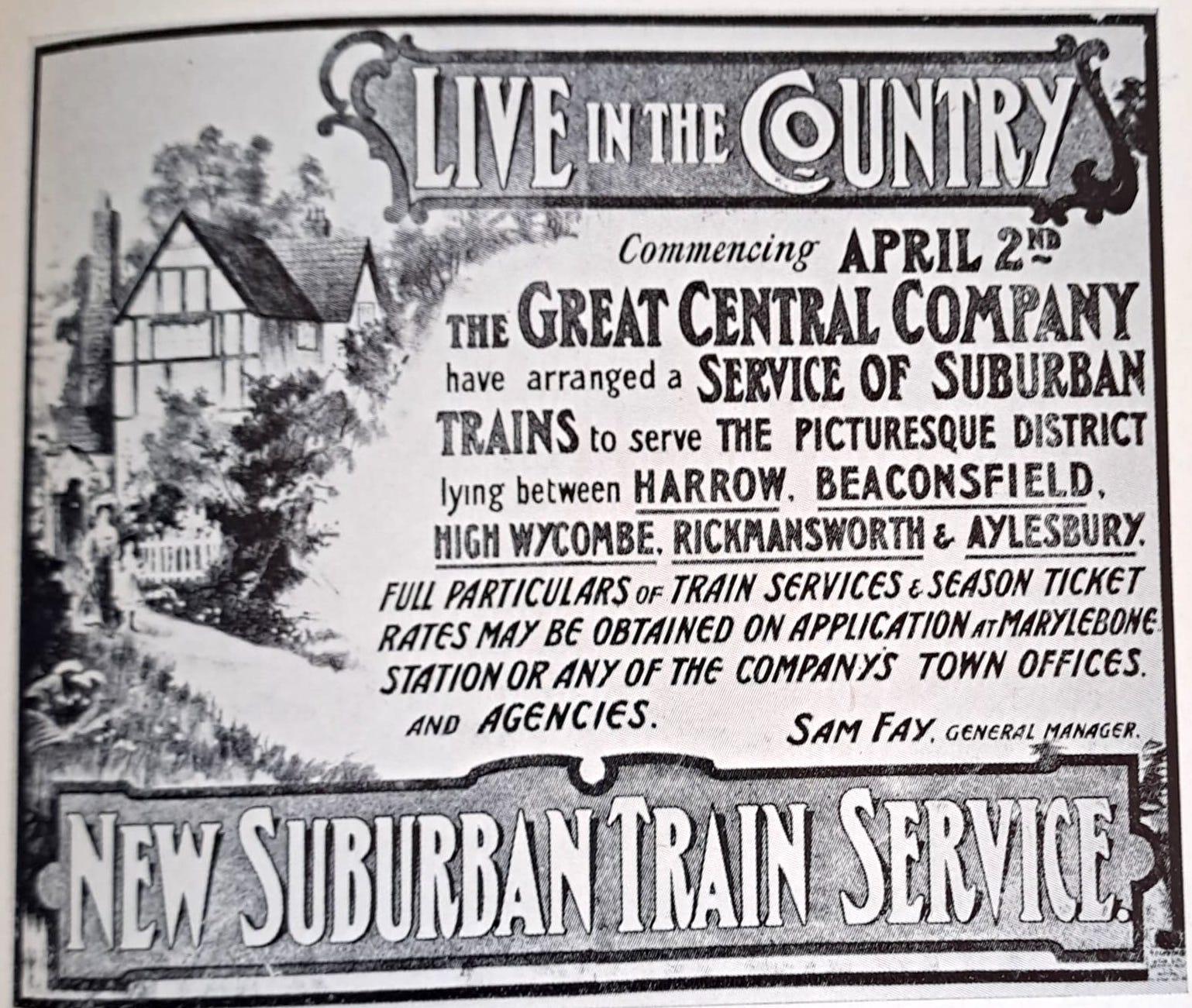

A reconciliation between the GCR and the MET was forthcoming when Sam Fay became the General Manager of the GCR and both companies agreed to form a Joint Railway Company of the existing Metropolitan Railway line north of Harrow-on the-Hill, as far as Verney Junction; this agreement would come into effect on 2nd April 1906, which so happened to be the same day that the GW&GCJR was opened to traffic.

Map of the Great Central Railway

The GCR main line would become a casualty of the Beeching Report (of 1963), as it duplicated the Midland Main Line and was thus thought to be superfluous and hence the stretch between Quainton Road and Nottingham is now disused, except for the two “Great Central” Heritage Railways - Great Central Railway (Loughborough) and Great Central Railway (Nottingham). There is every intention for the two to join forces, when the quarter mile “Gap” between them is re-established, which entails the construction of a reinforced concrete viaduct; planning permission for which is being sought as I write.

On the 15th March 2025, Marylebone will celebrate the 126th anniversary of the first “Down” Express to leave the station (in 1899), the destination, however is no longer the North of England as it was then, instead it is the West Midlands, with services to Aylesbury, Birmingham, Kidderminster, Oxford and Stratford-upon-Avon. Chiltern Railways are the present operator, but it is government policy to re-nationalise the passenger carrying sector under the banner of “Great British Railways” and its full franchise agreement is due to expire on the 31st December 2027, unless otherwise stipulated by the Minister of Transport.

The reprieve that Marylebone received thirty-nine years ago (1986) was a victory for common sense, as had it been closed the alternative terminals of Paddington and Baker Street could never have coped with the extra commuter traffic that would have been funnelled their way.

Post Script: It is worth mentioning that in 1985, when Marylebone was on the brink of closure there were a series of Steam hauled excursions to Stratford upon Avon, which were well patronised and film footage of Steam Engines leaving the station can be viewed on YouTube.

References & Further Reading

- “London’s Termini” by Alan A. Jackson, first published by David & Charles, 1969.

- “London’s Historic Railway Stations” by John Betjeman, first published by John Murray, 1972.

- “Great Central Railway: Volume II – Dominion of Watkin 1864-1899” by George Dow, first published by Ian Allan, 1962.

- “Great Central Railway: Volume III – Fay Sets the Pace 1900 - 1922” by George Dow, first published by Ian Allan, 1965.

- “Great Central Memories” by John M. C. Healy, first published by Baton Transport, 1987.

- “History of the Chiltern Line” by John M. C. Healy, first published by Greenwich Editions, 1992.

- “The Great Western & Great Central Joint Railway” by Stanley C. Jenkins, 2nd Edition, published by Oakwood Press, 2006.

- “Forgotten Railways: Chilterns and Cotswolds”, by R. Davies and M. D. Grant, first published by David & Charles, 1975.

- “Victoria’s Railway King – Sir Edward Watkin” by Geoff Scargill, published by Frontline Books, 2021.

- “Marylebone: The Underdog Terminus” by Jago Hazzard on his “YouTube” channel, 11:54 minutes long.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.