Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

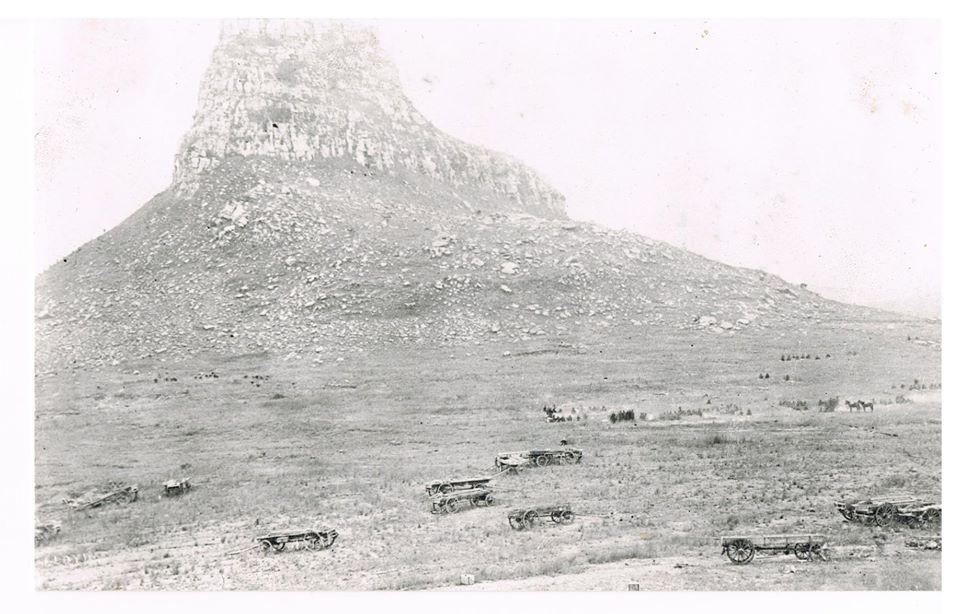

It lies in the darkness where it has been entombed for over 140 years, barely inches under the hard, stony soil of Zululand surrounding a curiously sphinx-shaped hill known to the locals as Isandlwana.

It is just a little piece of metal. Bronze, to be exact. Less than an inch and a half across. Shaped as a “cross pattee”, so the experts call it. The front displays a rather jaunty looking lion, bright eyed and particularly bushy tailed, trampling on a flattish-looking crown with pointed ears. Slightly dented from where its original owner’s chest was slashed to ribbons by a huge Zulu stabbing spear, the blood long since washed away, one can just make out the inscription “For Valour” written in a scroll beneath the crown.

The back is not so impressive. Merely a date, “7 May 1867” and along the top suspender bar “Pte. W. Griffiths 24th. Rgt.” The bar is bent and the piece is encrusted with the debris of a century, but the metal is still in surprisingly good condition.

Years of wind and rain have eroded the ground around it, dragging it reluctantly closer to the surface. Another couple of rainy seasons from now and it may well work its way out in a muddy torrent into the donga in front of Mahlabamkhosi, its face once again to be warmed by the harsh African sunlight.

Maybe, with a bit of luck, the right kind of human will be fortunate enough to find it. Someone who appreciates the wealth of history, courage, pride and outstanding achievement that it represents.

It has come a long way since it used to be part of a gun barrel of a Russian artillery piece in the Crimea. Looted by some red coated soldiers and taken away to England, the barrel finally ended up as a lump on the floor in the stockroom of Messrs. Hancocks and Co., Jewellers of London.

The Crimean War had been a particularly bloody one. More importantly, it had been well covered by war correspondents and photographers such as Roger Fenton. Pictures showing the full horrors of having your face blown off had given the Victorian establishment vicarious thrills and renewed pride in the achievements of her servicemen.

Siege of Sebastopol Crimea War (Roger Fenton via Wikipedia)

Prince Albert, in a fit of national pride, suggested to his wife that she should consider awarding some memento to her soldiers and sailors who had particularly distinguished themselves.

The upshot of all this was a piece that appeared in the London Gazette dated 5 February 1856 announcing the creation of Britain’s premier award for gallantry for all ranks since the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854. The two paragraphs applicable to this particular story were as follows:-

The distinction shall be styled and designated the “Victoria Cross” and shall consist of a Maltese cross of bronze with our Royal Crest in the centre, and underneath which a scroll bearing the inscription “For Valour”.

The Cross shall only be awarded to those officers or men who have served Us in the presence of the enemy, and shall have then performed some signal act of valour, or devotion to their country.

The award of the Cross also attracted a special pension of 10 Pounds per annum, but the Cross could be forfeited if the recipient was subsequently convicted of “treason, cowardice, felony or of any infamous crime….”.

The first awards were published in the London Gazette of 24 February 1857, and 62 of the 111 Crimean recipients were invested with their awards by the Queen on 26 June.

The criteria for the award were changed slightly by the Royal Warrant dated 10 August 1858, which provided that the VC could also be awarded “for acts of conspicuous courage and bravery under circumstances of extreme danger.… in which, through the courage and devotion displayed, life or public property might be saved.”

Victoria Cross (Wikipedia)

And that is where the story of this particular Cross begins. It is generally accepted that only seven Crosses were awarded under these circumstances until the Royal Warrant of 23 April 1881 declared that the Cross should only be awarded for “conspicuous bravery or devotion to the country in the presence of the enemy” and thus, by implication, revoked the 1858 Warrant.

5 of these Crosses were awarded to the 2nd. Battalion, 24th. Regiment of Foot (2nd. Warwickshires). One of these five recipients, William Griffiths, had the incredible misfortune to be at Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 when thousands of Zulus came storming over the Nyoni Heights, smashed through the British camp pitched at the base of the hill and annihilated the troops stationed there.

Memorial at Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

1867 had been a turbulent year for the British in Burma. It had been reported that the commander and seven crew members of the ship “Assam Valley” had landed on Little Andaman Island and been subsequently murdered by the natives.

A punitive and rescue expedition, of which the 2nd. Battalion, 24th. Regiment formed a part, was therefore sent out to investigate. On 07 May, some of the shore party came under pressure and there was a very real possibility that they would be attacked and annihilated by the natives.

However, very heavy surf was running and it was almost suicidal for any attempt to be made to get any ship’s boats through it in order to rescue the stranded soldiers on the beach.

Assistant Surgeon Campbell Miller Douglas, however, had other ideas. Calling for volunteers, he took four men (Privates Thomas Murphy, James Cooper, David Bell and William Griffiths – Regimental Number 1056; born at Roscommon and a collier by trade) with him in the second gig and attempted to make their way through the surf to the shore. Any hesitation or lack of commitment and effort would instantly have led to disaster, but the five took to it in manner born. They almost made it, but by then their boat was half full of water and almost unmanageable, and they were forced to abandon the attempt. Nothing daunted, after a short rest they tried again. Another herculean struggle through the combers ensued, but they finally made it to shore and managed to extricate five soldiers from the beach. The return journey was almost as bad, but the five were eventually passed to the safety of the boats lying outside the surf line.

Their third attempt was just as hazardous and just as successful, picking up another 12 men from the beach and returning them to safety.

“The four Privates behaved …. in a cool and collected manner, rowing through the roughest surf, when the slightest hesitation or want of pluck on the part of any of them would have been attended by the gravest results. It is reported that 17 officers and men were thus saved from what must otherwise have been a fearful risk, if not certainty, of death.”

These five members of the 24th. Regiment were awarded the Victoria Cross (London Gazette 17 December 1867) under the terms of the 1858 Warrant.

Some 12 years later, still a Private soldier, William Griffiths happened to be a member of Lieutenant Charles Pope’s “G” Company, 2nd. Battalion, 24th. Regiment on that fateful day at Isandlwana when his luck finally ran out.

He was tired. The Company had been on picket duty the night before, and no-one had got much sleep. Sentry duty is always boring, trying to peer through the darkness of an inky black night in an attempt to identify some sound or movement, either real or imagined. However, by 2 o’clock that morning no one could sleep through the hustle and bustle of Lord Chelmsford’s preparations to take a fast moving column out to the Mangeni valley in response to a report received of masses of Zulus to the south east of the camp. Lord Chelmsford was determined to get to grips with them as soon as he could.

However, it was plainly impossible to move the entire camp and its huge logistical chain some 12 miles down the valley in the three hours remaining before dawn. So Chelmsford made the fatal decision to split his column.

The 2nd. Battalion was designated to go with him, but because they had been out on duty the previous evening, “G” Company was left behind. As ill-luck would have it, some 12 hours later they were all destined to die.

Dawn came in Africa’s usual theatrical manner. A blazing ball of fire rising into the heavens accompanied by its outriders of cloud, tinged with spectacular hues of orange, red and yellow. Another scorcher!

Colonel Henry Pulleine, left in command of the camp and with orders to defend it against all comers, had earlier sent a company of men under Lieutenant Cavaye towards the Magaga knoll on the Nyoni Heights, where a small body of Zulus had been detected earlier.

Stand-to over, the men began washing up, performing fatigues and cleaning the camp lines prior to breakfast. As a further precaution, “A” and “H” Companies of the 1st. Battalion, 24th. Regiment had been ordered to a buffer position between the perceived Zulu threat and the edge of his vast, sprawling encampment.

Reports of another sighting of Zulus precipitated a general assembly. Breakfast forgotten the remainder of the men stood-to in a flurry. The alarm was quickly over, however. The Zulus withdrew to the north east in response to the aggressive move by the British and disappeared from sight. The men remained at stand-to for a couple of hours until, at Colonel Durnford’s suggestion, they stood down and returned to the tents, keeping their accoutrements on. Griffiths attempted to get his head down despite the increasing heat, ignoring as much as possible the myriad of flies buzzing around, and the gut wrenching spasms of oncoming dysentery.

The next thing he knew, the urgent and strident call of “Assembly” was being loudly bugled outside his tent. Pandemonium! “G” Company soldiers stumbled out from their tents, only half awake and clutching their accoutrements as they ran. The chaos finally began to sort itself out, the Officers and NCOs bawling at and cuffing men into line and checking their equipment, especially their quota of 70 rounds of ammunition. All of them, including Griffiths could see for themselves that the position had changed dramatically in the time that they had been fitfully asleep.

Lieutenants Pope and Godwin-Austin, both screwing their monocles in, pointed to the north east and east, where a black tide of warriors seemed to be emerging from the very ground and racing towards them over a four to five mile front.

Zulu warriors at Isandlwana, a re-enactment (Talana Museum)

“A” and “H” Company were already blazing away on their ridge, while to their north “C” Company was frantically doubling into position. The two 7 pounder cannon of N5 Battery, Royal Artillery, puffed white smoke into the air, accompanied by the “boom” some seconds later as the sound reached the camp.

Way out to the east, a small patrol of horsemen could be seen making their way back to the camp, pursued by what seemed like thousands of Zulus. The order came through for Pope to advance his Company in support. Griffiths and the rest of his mates were then doubled down towards the Nyogane donga, where the scouting patrol appeared to have taken temporary cover. Stumbling over rocks concealed in the tall grass, they arrived some 20 minutes later panting, sweating and exhausted. Most of their equipment had been discarded along the way. Unfortunately, much of their spare ammunition had also fallen out of their pouches in a shower of brass, but no one had any time to go back and pick them up.

The roar of the approaching warriors must have forcibly reminded Griffiths of the surf at Little Andaman. Nervously, he puts his hand inside his tunic where the Cross, now his good luck charm, hangs warmly around his neck on a piece of string. Sweating furiously, he thumbs a cartridge into the breech of his Martini Henry Rifle on the command “Load”.

Kneeling in the grass, hands shaking, the rifles come up on the command “Ready”.

“Fire!” A blast of hot air and gasses, clouds of white smoke, thump in the shoulder from the recoil. “Reload!” “Ready!” “Fire”.

The disciplined crash of volley fire roars out across the valley, and the front row of Zulus is blasted to bits. But there’s more behind. Thousands more.

Mates glance sideways at one another as the first tickle of apprehension makes their hair stand on end. The organized fire is degenerating now into independent fire as men fumble their reloads, frantically attempt to clear stoppages or wrap cloth around their overheating barrels.

And the Zulu wave bursts over them, only this time the result is not a waterlogged boat but a seemingly huge Zulu, face contorted with effort, crashing towards Griffiths through the donga. Dust flies around him, but he seems to bear a charmed life. Griffiths fumbles for yet another cartridge, but his pouch is empty. Frantically tearing at the pouch on the other side of his belt, he hardly feels it as the great 18 inch bladed stabbing spear thunks home into his chest, glancing momentarily off the little cross inside his tunic before burying itself to the hilt..

Blood erupts from the wound, his tortured heart pumping itself to death. He sinks to his knees as his assailant rips the spear out and rams it back home again and again, screaming “Ngidla!” – “I have eaten!”

Then the Zulu is gone, racing after further prey. And Griffith’s last thought as his eyes mist over is how peaceful it is, amidst the roar of the surf at Little Andaman Island.

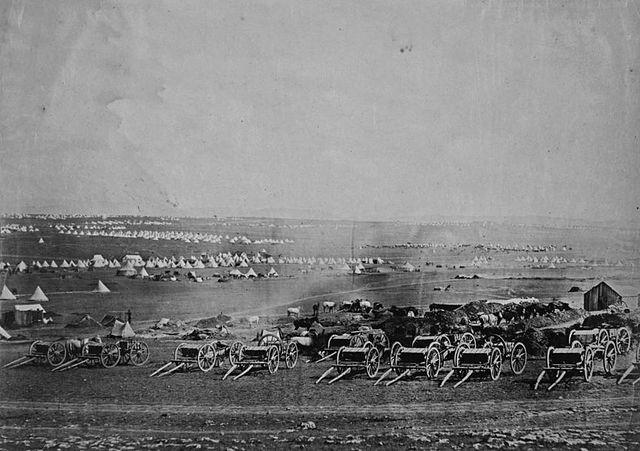

Aftermath at Isandlwana (Talana Museum)

And there his bones rest forgotten to this day. Until such time as that little Cross finally makes it back into the light and we once again are privileged to remember those heroes in their surf boat, risking everything for the sake of their mate’s lives.

R.I.P. William Griffiths!

Authors note: When this little story was first published many, many years ago by Irene Moore in “The Armourer”, it caused all sorts of hackles to rise and much vilification on the Internet. I was even accused of having found the medal and stolen it. But relax, dear readers, The medal is, and has always been, in the custody of the Royal Welsh Museum in Brecon.

Pat Rundgren was born in Kenya and grew up in what was then Bechuanaland and Rhodesia. He has nearly 10 years infantry experience as a former member of the Rhodesian Security Services. He is passionate about and has a deep knowledge of the battles, the bush and Zulu culture. He has written numerous articles on military subjects and militaria collecting for overseas publications, has contributed to several books and is currently busy with his eighth book. His wide ranging knowledge and over 20 years guiding experience and unique story telling will bring events alive to his listeners. His books “What REALLY happened at Rorke’s Drift?” and on Isandlwana and Talana have gone into a number of reprints. He is a collector of militaria with special focus on medals. He also organises and conducts tours around the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal and tours into Zululand to experience traditional and authentic Zulu culture and life style. Pat is currently the Chairperson of the Talana Museum Board of Trustees and one of the volunteer researchers.

References

- “British Gallantry Awards” by P.E. Abbott and J.H.A. Tamplin. Nimrod Dix and Co., London. 1981

- “Medal Yearbook”. Published annually by Token Publishing, Devon.

- “The Silver Wreath” by Norman Holme. Samson Books, 1979.

- “The Victoria Cross 1856 – 1920” by Sir O’Moore Creagh and E.M. Humphris. J.B. Hayward and Son, Polstead, Suffolk. 1985.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.