Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Magalies Memoirs focus on incidents in the Magaliesberg region and perhaps not everyone knows that it was here, in the heart of the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve, that gold was first discovered in the Transvaal, decades before diggers rushed to Barberton or George Harrison stumbled on the Witwatersrand Main Reef. “Discovered”, of course, needs to be qualified. We know from artifacts found at places like Mapungubwe and Thulamela that gold has been mined, treasured and traded for more than a thousand years – probably much longer. It was rumour of pre-colonial gold workings that lured 19th century prospectors into the interior of southern Africa. So this memoir really tells of the first re-discovery of gold in the Transvaal – an event that ultimately led to the metal becoming the backbone of the South African economy for the next century and a half.

Journey to the Magaliesberg

That important discovery was made by Pieter Jacob Marais, son of a wealthy Paarl family, well educated, enterprising and, although suffering from mild epilepsy, an intrepid adventurer. In 1847, aged 22, he left the Cape on the start of a voyage that took him around the world. First, he went to Liverpool where he heard about the California gold rush and immediately re-embarked for America. He failed to strike gold, and like many Californian diggers, he moved on to the newer goldfields in Australia. He returned to southern Africa in 1853 intent on applying his prospecting experience on home territory. The Sand River Convention, granting independence to the Boer settlers north of the Vaal River, had been signed the previous year and Marais trekked north to try his luck in the new Boer republic.

Pieter Marais and his wife Margarethe. (From Preller, Argonauts of the Rand)

When he reached the village of Mooiriviersdorp (Potchefstroom) he made friends with the Liebenberg family and began panning for gold, working from their farm outside Potchefstroom, northwards along the upper Mooi River into the Gatsrand. He kept a daily diary throughout his travels and this, now lodged in the National Archives of South Africa, has allowed historians to track his prospecting trip from farm to farm with considerable accuracy.

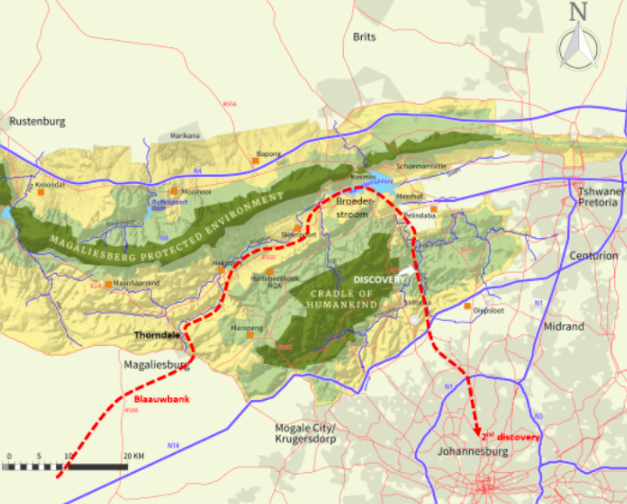

Ironically, he unknowingly traversed many places that later became significant in gold mining. He also met people who were to become part of the history of the region. As he crossed the Gatsrand, the richest gold reef in the world lay undiscovered thousands of metres below his feet, but the streams he panned in the dolomitic landscape yielded nothing. He then cut north-westward towards the Magaliesberg, passing Joseph de Beer’s farm, Blaauwbank, unaware that on that farm the wonderfully named ‘Nil Desperandum’ syndicate would open a successful gold mine 20 years later.

Marais’ journey of discovery (red dotted line) through the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve. (Map from Carruthers, Cradle of Life)

The following day he stopped at Thorndale, home of the famous elephant hunter, Henry Hartley, who would later guide geologist Karl Mauch to the ancient gold workings in Matabeleland and Tati and trigger the first gold rush in southern Africa. Poor Pieter Marais, it seems, had near misses wherever he went.

Thorndale lies on the Magalies River and Marais panned for gold all along that river, past Hekpoort, the home of Commandant Gert Kruger, brother of the more famous Paul, and on to the confluence with the Crocodile River, now submerged below Hartbeespoort Dam. There he met Andries Pretorius’s brothers, Bart and Piet, whose farm, Broederstroom, was named after them. Marais followed the Crocodile River upstream through Kalkheuwel, owned by Transvaal President Marthinus Wessel Pretorius, and on to the confluence of the Crocodile and Jukskei Rivers on the farm Vlakfontein. There, at last, his prospecting luck changed.

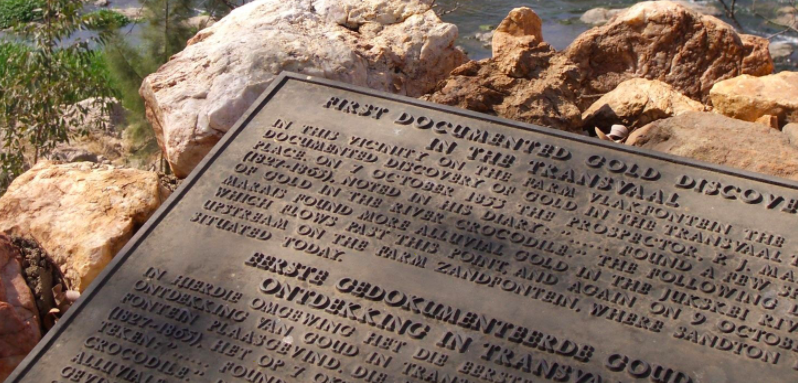

Two local farmers, Koos Botha and Tobias de Vlaming witnessed the moment on 7 October 1853, when Marais gently swirled the water in his prospecting pan to reveal a bright yellow band around the edge – the first gold ever panned in the Transvaal. Although we now know the historical significance of that event, Marais’ diary simply states: “…found a few specs of gold in the River Crocodile.”

The consequences

Marais’ ‘few specs’ were followed by another minor find in the Braamfontein Spruit, one of the upper tributaries of the Jukskei, in Sandton but persistent searching yielded nothing further. In December 1853 he reported his finds to the Volksraad in Potchefstroom and sought permission to continue prospecting. After several days of negotiation, he signed what is believed to be the first mining contract in the Transvaal. It was a double-edged sword. Article 5 offered him a generous payment if he discovered gold ‘which promises to profit to this country’ plus the right to manage the resulting mine on behalf of the government. However, Article 12 threatened ‘the penalty death with no extenuating circumstances’ if he divulged his finds ‘to any foreign power… causing the independence of the Republic to be disturbed or threatened.’ The Raad appointed two assessors and Marais was required to report any discoveries to them. The Boers were clearly concerned that the discovery of gold might revive British interest in their country – a prophetic expectation.

Plaque commemorating Marais' find in the Braamfontein Spruit

Panning for gold in the Braamfontein Spruit (The Heritage Portal)

For the next two years Marais continued to travel through the Transvaal diligently searching for gold. Meanwhile, exaggerated tales of his ‘discoveries on the Yokeskeys River’ were leaked to the Bloemfontein press, not by Marais who faithfully kept his commitment to confidentiality, but by some unknown person from the Magaliesberg who knew of his find. The reports aroused the suspicions of the Volksraad, and when Marais wrote on 7 April 1855 to say that he had found nothing more, they rejected his statement and summonsed him to appear before the Raad. Before the order reached him, however, he had abandoned his gold-seeking life and returned to the Cape Colony. There he married and settled down as a trader and wool broker in the sheep farming district of Dordrecht.

There are two other contenders for the title of first discoverer of gold in the Transvaal. The name of Karel Kruger, a hunter in the region in the 1830s, is sometimes mentioned but there is no evidence of what he found or where he found it. A stronger claimant may be John Henry Davis, who is said to have found gold at Paardekraal, (Krugersdorp) in 1852. However, Davis’s story is undocumented hearsay and it is so similar to that of Marais (i.e. an experienced prospector, born in Paarl, was to be paid for his discovery but left the country hastily) that Davis’s discovery was possibly manufactured.

Geological origins

The source of the gold dust panned by Marais at the Jukskei is likely to have been the Black Reef that runs through the Magaliesberg Biosphere Reserve. Billions of years ago tectonic shifts thrust part of what is now the Magaliesberg landscape underwater so that rivers from the highlands flowed into bays along a new coastline. Silt and gravel, including some alluvial gold, accumulated in the shallows, and consolidated into quartzite conglomerate known as the Black Reef – quite distinct from the Witwatersrand gold reef. More sediments were deposited over time like a Dagwood sandwich, and were later tilted at an angle of about 20 degrees, exposing the edges of each sedimentary layer as a series of rocky ridges known as the Transvaal Supergroup, or Bankenveld. The oldest ridge, the Black Reef, is on the south and the most recent, the Magaliesberg, lies to the north.

The ridges obstruct the flow of rivers, which unite to cut passages through the uplifted barriers. The confluence of the Crocodile and Jukskei is one such union, and as it slices through the gold-bearing Black Reef, it erodes out the grains of gold that Pieter Marais discovered two billion years later.

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Sources

- Coates, P.N.A., ‘Pieter Jacob Marais’ search for gold in the Transvaal’, Contree, 22, 1987, pp.31-33.

- ‘Marais, Pieter Jacob’, Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol. II. Pretoria: HSRC; 1972, pp.445-446.

- Gray, J., Payable Gold. Johannesburg: CNA; 1937.

- Letcher, O., The Gold Mines of Southern Africa. Johannesburg: The Author; 1936.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.