A woman of many firsts. Among these is the fact that Nokukhanya Luthuli was among the first students in the early 1900s to attend all three of Durban's legendary mission education schools.

As a young girl she was a pupil of Ohlange Institute, a school started by John Langalibalele Dube, a good friend to her father, who was later instrumental in the founding of the African National Congress and who also started South Africa's first black-owned newspaper. She went on to matriculate at Inanda Seminary, recognized for its unheralded role in black women's education in South Africa. She then completed her teacher's diploma at the famed Addams College, near Amanzimtoti.

It was under the sweltering heat of a Durban summer in February 1990, amongst a 150 000-strong politically charged crowd that the author became aware of the subject's remarkable life.

It was just after he had famously proclaimed, “Take your guns, knives and pangas, and throw them into the sea", that Nelson Mandela requested that an unrecognizable old woman, dressed in a bright but a little oversized white summer dress and walking with aid of a walking stick, approach the stage.

"Ï have a present for you", he told the crowd. "I have here with me the Mother of the Nation, Nokukhanya Luthuli. I want you to receive her by shouting loudly and saying "Nokukhanya!" three times." The crowd clapped their hands and raised their voices high beyond the stadium's walls and shouted in unison, "Nokukhanya!", "Nokukhanya!", "Nokukhanya!"

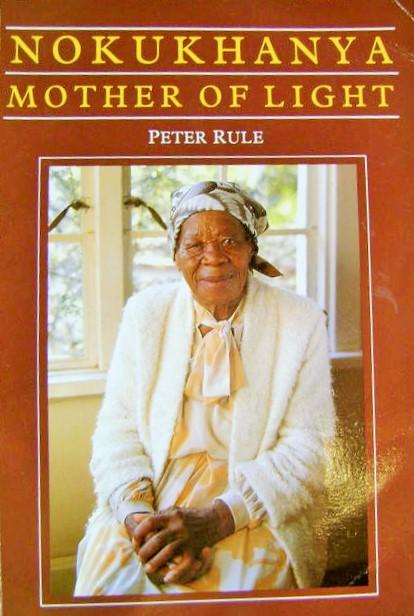

Nokukhanya Luthuli (Luthuli Museum)

In Nokukhanya - Mother of Light, author Peter Rule, weaves through a tapestry of a life so remarkable yet relatively unknown in South African public life. This is the story of Nokukhanya Luthuli, nee Bhengu, wife of erstwhile African National Congress (ANC) leader and Africa's first Nobel Peace Prize winner, Chief Albert Luthuli. Far more than just being the wife to a celebrated struggle hero, the book demonstrates the fact that Nokukhanya's life had impact well beyond this fact.

Book Cover

Personally, I was drawn to Nokukhanya's story by her personal journey through mission education in KwaZulu-Natal in the early twentieth century. The book touches on this in an ample and encompassing manner. For starters Nokukhanya, whose royal blood dates back to her paternal grandfather, was born and reared at a time when there was, amongst African communities, a clear distinction between Christian believers and non-believers.

Her father, Maphitha Bhengu, was one of the early Christian converts of the Umngeni American Board Mission, and it was at the Umgeni Mission Station that a girl was born on 3 March 1904, Maphitha`s sixth and last-born child. She was christened with the name Nokukhanya - Zulu for Mother of Light.

"Our family aspired to be achievers in the civilization with which they were coming into contact through the British settlers and the missionaries in the Natal colony “, she states in the book. “By giving me the name Nokukhanya, my parents were expressing their wish that I should grow up and play my part in bringing the light to our people. The light at that time translated into education and Christianity."

As stated earlier, and according to the book, Nokukhanya's place in mission education heritage is unique. She is among the students placed on record as having been in the position of having attended all three of the then Natal colony's prestigious mission education schools in Durban.

This fact alone puts her at the centre of mission education in Natal at its most significant and pivotal period, at the turn of the twentieth century. Her attendance of John Dube's Ohlange Mission Institute put her in touch with the "black economic independence and self-reliance" philosophy inculcated into the school ethos by Dube after his stay at Booker T Washington's Tuskgee Institute in the United States.

At Inanda Seminary part of her routine would have been the domestic and industrial, designed to make the girls turn into productive and efficient homemakers. At Addams College, Nokukhanya certainly came into contact with men and women who would later become esteemed members of the black community, for their work in politics, education etc. Amongst these was a lecturer, and the man who would later become her husband, Chief Albert Luthuli. Interestingly enough, their time at teacher training college at Addams College was not the first time they had been in the same institution. Unbeknownst to them, they had both been primary school students in the same years at Ohlange Institute.

As in a number of other books that touch on mission education in South Africa, the book paints an elaborate picture of the stark differences between mission education and its aftermath, Bantu education. The most glaring of these differences is race. The separation of races was of crucial importance in the execution and maintenance of Bantu education. In direct contrast, the free-mixing of the various racial groupings was an objective espoused and encouraged by mission educationists. This fact is very much evident in Nokukhanya's education, from Ohlange right up until she received her teacher's diploma at Addams College.

Given Nokukhanya and Chief Albert's close propinquity with mission education, it is somewhat of a conspicuous omission that this family legacy is not brought further into the twentieth century by the author. Where did the Luthuli children, largely present in the book, receive their education?

In its entirety, Nokukhanya - Mother of Light paints a comprehensive picture of how the various elements of life - roots, upbringing, joys, pain, hardships and milestones conspire to channel the life of one woman to great societal significance. Nokukhanya - Mother of Light is a worthy addition to the comprehensive study of mission education in South Africa.

"The Mother of the Nation"

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg.

After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue.

On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa.