Sometimes it takes a foreigner to recognize a powerful South African story. The title is arresting Barnato’s Diamonds. Such a title must surely refer to the diamonds owned or mined by Barney Barnato the flamboyant mining pioneer who made his first fortune in Kimberley in the 1870s and his second fortune on the Witwatersrand and Johannesburg after 1886. He was the man who founded Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Company, affectionately called “Johnnies” or JCI. Barnato was involved in everything that made Johannesburg, the mining camp that became the new glittering golden city. His company got involved in all enterprises, from diamonds to gold mining, from property development to potable water provision, from hotel development to theatres. The establishment of the JSE, (the stock exchange) owed much to Barnato.

Consolidated Building Johannesburg (The Heritage Portal)

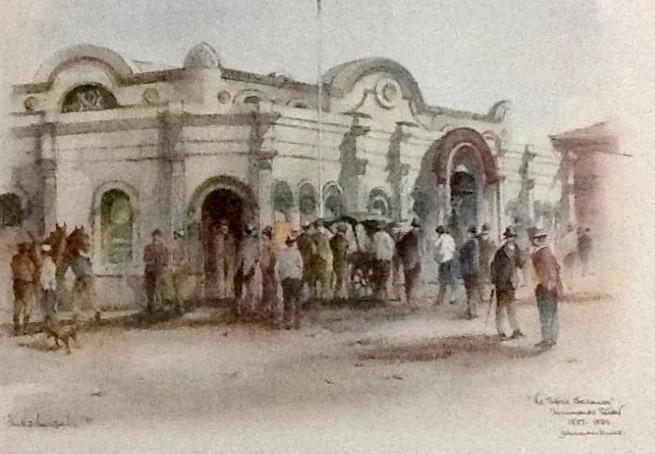

Philip Bawcombe drawing of the First Stock Exchange

However the diamonds of this book had nothing to do with real diamonds and little to do with Barnato but echo the biblical quotation in the Book of Proverbs that the worth of a good woman is far above diamonds. This book is all about the school girls who were educated at what was then the oldest girls school in Johannesburg – Johannesburg Girls High School or JGHS - in a specific period of five years, from 1957 to 1961. JGHS was colloquially called Barnato Park.

This book is a case study of the class of 1961, a group of 115 girls who the school shaped to become young women over their five high school years. However, the focus is actually on 28 old girls who responded to a questionnaire. They were asked to respond to questions on the topics the author wanted to probe: heritage, grandmothers, parents, domestic servants, childhood, language, religion, the holocaust and the Second World War, apartheid, race relations, politics, marriage, feminism, nationality and identity. There were questions about what you felt when you voted in 1994 and whether you are optimistic or pessimistic about South Africa - so the book flows and grows beyond school life – forwards into adulthood and backwards into ancestry.

Book Cover

This book pulls together the stories of female lives and their family histories. Lives lived in South Africa in the shadow of apartheid. This is a book about Johannesburg lives of the 20th century. We have no way of knowing whether the 28 women who responded do actually represent the other 87 girls who were in the class of 1961. These missing women were not located some 60 years later. Nonetheless it is quite a feat to capture the stories of even 28 women, 50 to 60 years after the attended JGHS.

The backdrop to this book is both the history of the school and the history of Barnato and his Barnato Park. The author does not seem overly interested in either Barnato or the history of the school - as Barnett Isaac Barnato (1851 – 1897) gets no coverage at all and the school’s history is briefly and very incompletely covered in a final chapter.

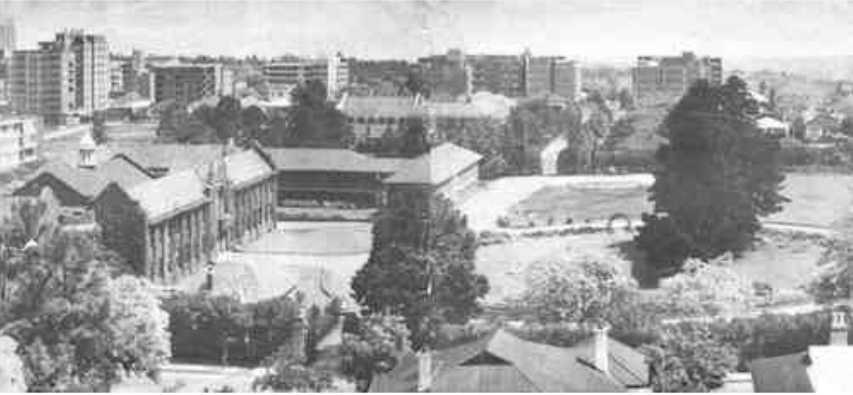

Johannesburg Girls High School - Barnato Park circa 1965 / 1966 after the demolition of Joel House (from the School Magazine cover for 1966 - K A Munro copy). Notice that the old Joel House, Barnato’s mansion, has disappeared. The 1912 school is still there and to the north is the Corlett Wing.

To explain, the school was located at Barnato Park, the old estate of Barney Barnato in Berea. The boundary streets are Tudhope Avenue (east), Barnato Street (south), Beatrice Lane (west) and Park Lane (north). The estate fills the equivalent of six residential blocks or about 11 acres.

In 1961, the mansion built for Barnato in 1897/1898, still stood. The house and the estate had a curious history. He had decided to build a Johannesburg home on his estate at the centre of his company’s own Berea township. According to the Africana Notes and News article by Oscar Norwich, the cost of the mansion was £8 000 and was modelled on a similar house in England, presumably as a country residence. I have yet to establish the model for the Barnato Park mansion. Barnato drowned at sea en route to England in the middle of 1897 so he never lived in the mansion he commissioned. The house was inherited by his nephew and came to be called Joel House (see main image).

It was a grand home on a large estate with a lake, a circular drive, four imposing gates, and a gatekeepers lodge at the south gate. The mansion was demolished in the early months of 1963. The school was a government high school, single sex (an all-girls school) located in the suburb of Berea on the edge of Hillbrow, offering a very British education. For 103 years it was the premier Johannesburg state girls school, progressive in offering the girls aged 12 to 17 access to high quality education. But the negative was that it was a school only for white girls - and one can take a facile line and immediately dismiss the role of the school as serving the privileged elite. I think that would be too quick a response, first read this book.

I should at this point in my review declare an interest as I was in the class of 1962. I matriculated a year later than the girls of 1961. I owe that school a huge debt of gratitude.

The original gates to the mansion (The Heritage Portal)

An undated but fairly well known photo of Joel House - the figure is said to have been Miss Fanny Buckland, the founder of the school.

The front cover of the school Hymn book with the school badge set in a wreath (Kathy Munro)

Unfortunately the author does not probe the functioning of the school and how it really worked. But the book certainly sparked my memories about a school life of some nearly 60 years ago. It led me to write my own memories of school life.

I was fortunate. I came to be educated at the University of the Witwatersrand because I was awarded the Old Girls Bursary. I have always been interested in the history of the school and in more recent years reflected on the significance of the education we received and what it meant for a white female teenager in apartheid Johannesburg and to be the beneficiary of privilege which so many others, black and white, boys and girls were denied.

Great Hall at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

JGHS was a school where privilege was acknowledged and while we did not feel guilt, we felt a duty and a responsibility. I remained interested in this school for many years and attended the centenary celebration of the school in 1987. Little did we know then that the school as we knew it was in its death throes).

Let me now set out the history of the school. It was founded by Miss Fanny Buckland and opened in 1887, as a small coeducational establishment for children of all ages, in downtown Johannesburg under a different name, in a different location. Fanny Buckland earned an entry in the Dictionary of South African Biography (Vol 4) and was identified as one of the Seven Builders of Johannesburg in a small book by that name by Juliet Konig (along with Fred Struben, Ignatius Ferreira, Capt. Von Brandis, W. A. Pritchard, John Darragh and James Gray). Starting as Miss Buckland’s school in the living room of the Alexander family, it later moved to a room in Kerk Street that belonged to the Baptist Church and in the 1890s located to Leyds Street, when an American mining engineer and philanthropic family, Mr and Mrs Henry Perkins, financed a proper school building and the school was named Cleveland High School after the Perkins’ only son. In her memories of her school, Miss Buckland joked that her school was often called Saint Bucklands (as though it was a latter day St Trinians). The school passed through a good many changes and came to be located in Berea at Barnato Park in 1912.

There is a complex story as to how Barnato Park and Barnato’s fine new mansion, in grand English country house style became a school and what happened from 1897 (when Barney drowned in the Atlantic and his mansion in Johannesburg was left to his heirs) and 1910, when the house and grounds were gifted to the new South African Government to commemorate the Union of South Africa and then passed to the Transvaal Education Department to use as a girls’ school. During the Anglo Boer War the mansion, after the British occupation of Johannesburg, became a convalescent home for British Officers. After the Boer War, the Johannesburg College, a school for boys and the predecessor of King Edward VII school took over the Barnato Mansion and estate. There are some wonderful photographs in AP Cartwright’s History of King Edward School. When that school moved to their new buildings in Upper Houghton, Miss Buckland’s school was the one chosen to be the newest occupant and the name of her school changed to Johannesburg Girls High School. The estate was a good location for the school as it was accessible from all directions by public transport– it was central but still had a suburban feel.

Old photo of KES (SA Builder Magazine)

A new school building was erected in 1912; the architect was Piercy James (Patrick) Eagle working for the Public Works Department of the Transvaal. (Source: Artefacts website). This building was the fine Queen Anne style building in a reddish face brick with a main central entrance and two quadrangles, double storey, purpose built - a mix of classrooms, fronted by a cloister style open corridors, library, music room and art studio. Group photos of classes past lined the staircases. The roof was tiled with orange clay tiles. Joel House with its 50 rooms remained as the boarding house and home of the headmistress. There was a school hall dropped into the space between the two quadrangles, with a clock tower above. In the 1950s a new wing, the Corlett Wing (named for DF Corlett who was interested in the school and a great benefactor) was added. Joel House (Barnato’s Mansion) was demolished in 1963 and the main old school building disappeared in 1970s when the new rather non-descript school buildings without quadrangles and clock towers took its place. The white government school, the original Johannesburg Girls High School closed in 1989. The school buildings then opened in 1990 as a coeducational multi-racial high school, called Barnato Park, it was a private school and had a very short life - just a year, because in 1991 the school reverted to government status - for the boys and girls of Hillbrow. It is a long and fascinating story with many strands and byways. Throughout its history, the political context, national and local, and the changes of an urban environment determined the shape and functionality of the school. This was and still is a city high school and inner cities are places of migration and demographic flux.

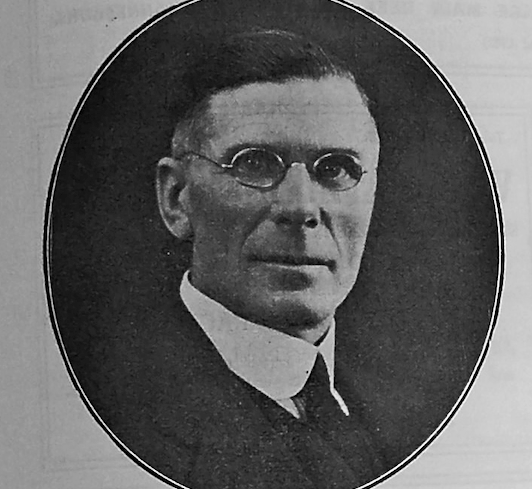

DF Corlett (SA Builder Magazine)

Today there is a government school at Barnato Park, coeducational, boys and girls and it is a multi-racial school. Many pupils come from families who have immigrated to South Africa from other parts of Africa. Pupils wear a new uniform (the colour is red), there is a different ethos serving the new populations of Hillbrow, Berea and Yeoville. When I visited the new school five years ago, the pepper tree brought back memories but our beautiful science laboratory has become a photographic club and any child with a talent in science has been short changed. Today it is theoretically a multi-racial school but all the pupils are black; there has been white flight. The era of an all-white, all girls British modelled establishment is dead history. Something of this story comes at the end of Barnato’s Diamonds.

The book makes for a fascinating read though it was not exactly the book I anticipated. The story will appeal to many Johannesburg people and those old girls who emigrated from South Africa to become immigrants elsewhere. Essentially it is an oral history. The author encountered “GL” (a woman in the 1961 Barnato Park matriculation class) in the USA, who inspired the author because GL had an unusual tale. The interview material has been used to create a montage of glimpses of growing up in Johannesburg, how their families came to be in Johannesburg, their family roots, what they did with their lives etc. Of course all of this cohort are now in their seventies so these are memories of childhood, mothers, grandmothers, fathers, domestic help / servants, marriage, school life and more. There are chapters on language, religion, feminism, attitudes to apartheid, race relations and politics and what everyone felt like when they voted in the first free election of 1994. There is a chapter on nationality and identity and how this group view the future of South Africa. The author uses direct quotes from interviews and as everyone is anonymous, it’s a mish-mash and a muddle of reminiscences. No one is actually named other than by their initials in a biographical appendix of who was interviewed or contributed. I think that is a weakness.

This is also a Jewish story as the author relates the stories of many Jewish immigrant families to South Africa who arrived in the thirties from places like Germany, Italy or Lithuania. Many settled in Berea or Yeoville or Bellevue, married, had children, made good and progressed up the social ladder, perhaps moved to Houghton - and sent their daughters to Barnato Park. But the time spent in South Africa for so many white families was limited, perhaps to a few decades and the next generation in the wake of political and social turmoil and uncertainty emigrated to the USA, back to Europe or to Australia. Of the group who contributed, approximately 12 live elsewhere in the world - or if they did not leave, their children have left. It is such a white South African story of family disruptions and migrations. So many white families who came from elsewhere left South Africa in the 1980s because life became more uncertain and it seemed the country was heading to revolution.

The reflections and memoirs are fascinating and frustrating because photographs are anonymous and you don’t know whose “voice” you are reading on any one page; or whose grandmother is described as 'strong willed and immaculately dressed and ambitious'. Each chapter is a patchwork or a collage of voices. The author (though she must have visited Johannesburg) does not know local geography and gets basic names wrong - as in Durban is Durbin and Berea is Beria. Her strong interest is in personal heritage and families so it is a people oriented book - there really is no proper context to grappling with the school’s unique history, what type of education JGHS offered in its heyday.

Yet the book is appealing because it also echoes my own story. I was the child of an immigrant English father; my mother was South African – a strongly independent woman who had great ambitions for her bright daughter. My father was more sanguine and just wanted to make a new home in South Africa and get away from impoverished, class riven post war England and to forget that he had been fighting a war. So if you are of my generation you will read the book with your memory slipping back to your own childhood and school days.

I was able to work out the names and remember three of the girls of the 1961 class represented by their initials and each went on to a remarkable career. The class of 1961 did have some outstanding young women (but so did each year). Vivian Fritz became the Professor of Neurology at Wits, a most prominent and much beloved specialist doctor. It was remarkable that so many of the girls educated at Barnato Park became academics, entered the medical professions, went into business, became writers or became teachers.

The book adds to the Johannesburg literature. Sharon Mount recognized that in meeting a former pupil of the school, she had found a key to a special South African story. She has tried to understand “roots and shoots”. We never knew when we were at school that this was a fleeting moment in time both in our history and in the history of South Africa.

If you were a pupil at the school and happen to own similar photographs to the one on the front cover, you will want to read this book and sigh at the days gone by.

The way in which the author writes is likely to appeal to an American audience so the frustration comes back as this is not the whole story as a South African writer would have told it. There are so many omissions. I don’t think the author understands the socio-economic complexities of the close proximity but distance between Houghton and Berea/Yeoville or what it meant to be a school on the edge of Hillbrow.

The Form V A class of 1962 with Miss Hodkin - Johannesburg Girls High School. This is my own school photograph of my matric year. Yes I am in the photograph and yes, I can identify every single bright young face in the photograph. Some have passed on. In 2012 we celebrated our 50th reunion.

The school song on page 345 is not in fact the School song of our era. The author has included a school song written by a Dorothy Welsh in 1919. But the school song we sang is this one and for the sake of accuracy I include it here:

Vincemus

Oh, the world is wide and its schools are many,

And Africa's schools are as fine as any;

But Barnato Park is beloved of all

Who have watched her growth from a nursling small

To the school that we honour and love to-day,

So we'll cheer our Founders with this refrain:

" Vincemus! Vincemus! We'll win yet again!"

We've a Bath for swimming and a Hall for "gym"

For we must be supple and fleet of limb

In a land where such sports are conducted in style

By the Springbok, ostrich and crocodile;

And at seasons proper we stake our fate

On a contest grim, but devoid of hate,

And we cheer the victors with this refrain:

"Vincemus! Vincemus! We'll win yet again!"

Oh, years of freedom, how fast you flee!

We shall yearn for you in the years to be.

For the joy of striving with all out might

To play as a team, with the goal in sight;

For the love of a friend who will see us through

Whatever the hazardous things we do;

Yet we'll greet the future with this refrain:

" Vincemus! Vincemus! We'll win yet again

Words by a Miss G Johnson and the music was by John Connell (the City Organist of Johannesburg).

To indicate where a few of the problems are in the Mount book:

- It is Sabi not Swabi

- It is Parktown Convent not Parktown Commons

- It is Durban nor Durbin

- It is Clarice Cliff not Clarence Cliff

- It is shilling not schilling (the currency was pounds shillings and pennies before Rands and cents)

- It is Gandhi not Ghandi

- It is Munro drive not Monroe

- Its Boksburg not Bucksberg

- It is Berea not Beria

- It is Alan Paton not Allen Peyton

- It is Clive Derby Lewis not Clyde Derby Lewis

- It is Parktown Boys not Clarktown Boys

- It is sight not site (page 248)

- It is radio technician not radiotrician

- It is Turfontein not Terventine

- It is Basle not Basil (place in Switzerland)

- It is Hope Worldwide not Hope World Wyatt

Spelling inaccuracies: ‘platte’ should be ‘plait’; ‘broche’ should be ‘brooch’; ‘extraverted’ should be ’extroverted'; ‘lip scheme’ should be ‘lift scheme’. These errors irritate and show the limitations of self-publication where the author can't employ of spell checker or a fact checker.

In summary an unusual book about a familiar and well know subject (for this reviewer). With all its errors and omissions, it comes with my recommendation because it captures a Johannesburg education of a particular era.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.