There is enormous interest in early African history. It is a growing field with old assumptions and theories about settlement patterns in Africa challenged, overthrown and reinterpreted. Who were the past societies and communities of Southern Africa? Where did they come from and when? What were the patterns of migration and conquest? Where did people live, how did they live and what happened to these early societies? We have far more questions than answers. The paucity of written historical records means that to advance scholarship there has to be an alliance of disciplines – history, social anthropology and most important of all, archaeology.

Traditionally, African history has invariably started with European exploration when the Portuguese monarch dispatched the intrepid voyagers such as Bartholomew Diaz and Vasco Da Gama to head south from the Iberian peninsula to explore the African coast, to show that the world was round and find a sea route to India. It was all for economic gain of Europeans and to the economic disaster of Africa. Inroads into Africa from the coast proved to be catastrophe for what the authors term, “the Zimbabwe Culture States of Torwa and Mutapa”. After 1500, new Portuguese settlers interested in a possible trade in gold arrived to trade, plant settlements and to conquer. The tactics were both offensive and defensive. A fort was erected on the coast at Sofala (south of modern day Beira on the East coast of Africa). The Portuguese were not the first economic predators. They crossed swords with Arab and Swahili traders who were well established at Sofala. The Portuguese defeated the Moors as they called them and so began penetration inland by the new adventurers, treasure seekers, traders and settlers. Later came the missionaries to convert and to embed conquest. In what we today know as Mozambique, the Portuguese crown claimed vast tracts of land between the sea and the inland Mutapa Kingdom. The story of what happened as kingdoms clashed and the musket, bible and hoe were the weapons of conquest is told in the final chapter of this book. This is the stuff of recorded history.

To go further back in time we need to study the artifacts, the structures and the remnants of earlier societies and here we must rely on the archaeologist to guide us through the Southern African kingdoms. We are dependent on the trained professional to study and interpret the rocks, the stones, the shards and the small objects.

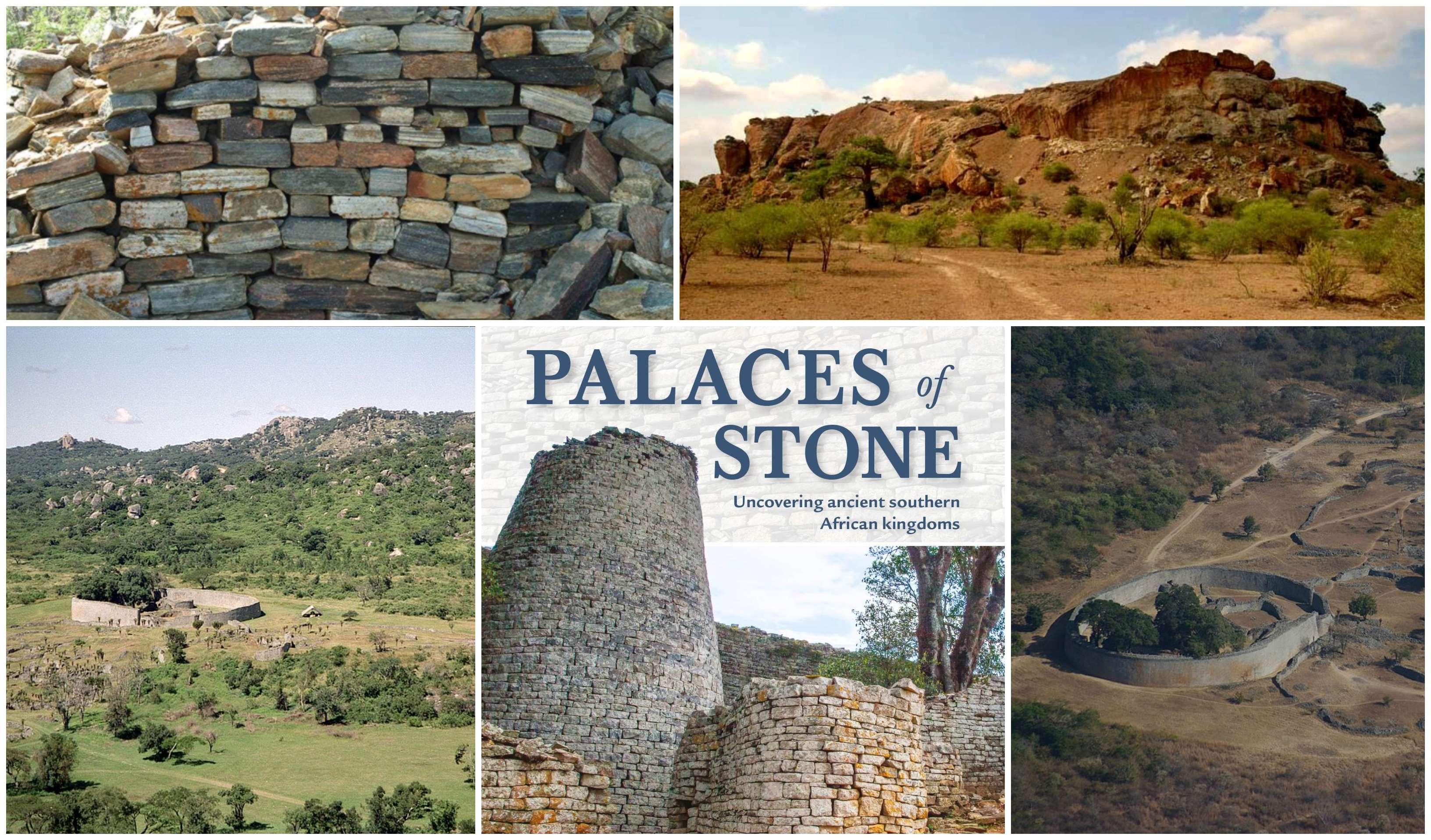

The ruins of more than 566 stone palaces exist in southern Africa. Great Zimbabwe and the Khami Ruins in Zimbabwe are world heritage sites, as is Mapungubwe in South Africa, but almost all of the others are not widely known to the public. The archaeologists who study these sites know the most.

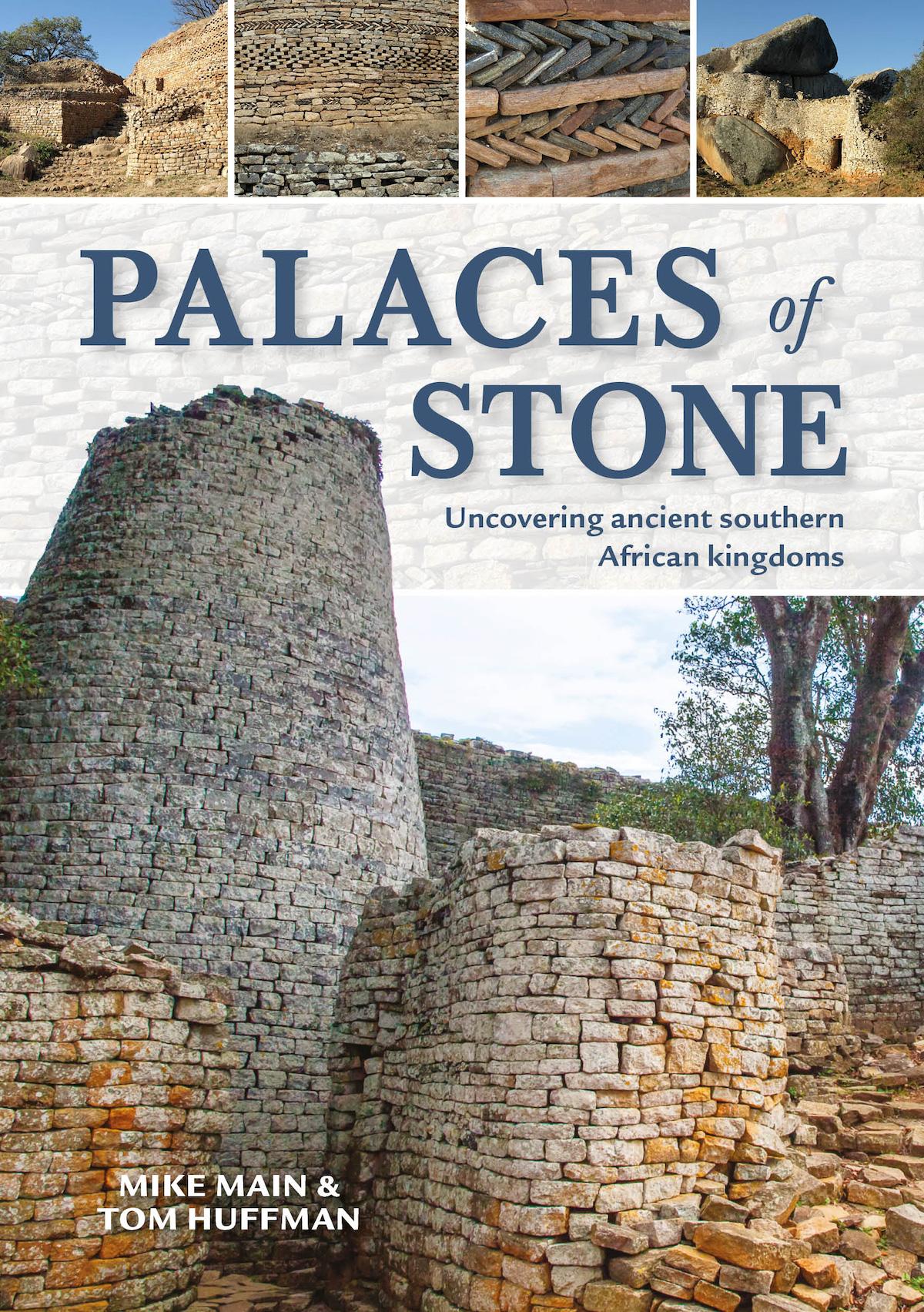

This situation is about to change due to this single new guide book. Covering the period AD900 to 1850, the authors, professional archaeologist Prof Tom Huffman (who held the Chair of Archaeology at Wits for many years) and management consultant and lay archaeologist, Mike Main share their knowledge of southern Africa (four countries are covered, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa and Mozambique) as an archaeological treasure house.

Book Cover

Their objective is to introduce the archaeology of Southern Africa and raise an awareness of hundered of ruins, stone structures and fingrerprints of settlments covering the period AD 900 to approximately the mid 19th century. Archaeology is the bridge into understanding the meaning of these tantalizing remnants, rocks, walls and stones.

There is a grand legacy in these mysterious kingdoms and stone palaces across a region the size of France. As mentioned, the layman knows about Great Zimbabwe but most people know hardly anything about the archaeology of a far vaster area. Throughout the region over Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa (broadly southern Africa) these stone walled ruins all follow the same architectural style. The authors make the critical point that some have been brutally plundered, very few have been properly excavated and even fewer have been correctly dated. The authors strive to fill the yawning gaps and to share and and interpret the evidence. These archaeological sites are underappreciated because the story has not been told to a large enough audience. Their aim is to teach, and most important of all to allow their enthusiasm to become infectious.

Archaeology today is a precise science based on exact measurement. The archaeologist records not only built structures and remains but also artifacts buried in layers of seeming discarded debris. He sifts the sands of time to tell the history of past societies. Objects like ceramic shards, pottery fragments, glass beads, metal arrowheads or even something extraordinary like the golden rhino from Mapungubwe have been unearthed and must be explained. The trained archaeologist destroys as earth layers are dug into and items removed for study. The science lies in the keeping of comprehensive records as to what has been found where. Modern archaeology is an academic discipline and a science. The archaeologist analyses, measures, dates, and draws grounded conclusions about the artifacts in his hands. The finds open a window on past societies. There can still be guess work and theory but the knowledge and peer evaluation of research and building upon what has already been studied pushes boundaries all the time.

This gold foil bowl was one of several artifacts recovered from the burials at Mapungubwe Hill during excavations in the 1930s (Palaces of Stone)

This gold sceptre was excavated from an elite male grave at the summit of Mapungubwe Hill in the 1930s (Palaces of Stone)

Most famous of all finds at Mapungubwe was the Golden Rhino made from Gold sheeting and pinned onto a wooden model with gold tacks. (Sian Tiley-Nel)

There is also a subtext about the development of archaeology as a discipline, as the slow move took place from looting and treasure hunting to science and proper documentaiton and then much more scientific interpretation. It took a long time for archaeology to become respectable but it was always a glamourous subject as the lure of treasure drew the men who could only be described as looters. But there is nothing glamourous about being an archaeologist today - it is back breaking work.

The core of the book is on Great Zimbabwe but context is set with the initial discusison of the finds at Schroda and Mapungubwe. For centuries so many of Africa’s great archaeological sites, such as Great Zimbabwe remained unexplored. Early travellers sometimes wrote up accounts of what they had seen but there were no written records left by the original inhabitants. Romance and myth took over where there was no history and writers such as Rider Haggard encouraged the fantasies and dreams of the treasure hunters who sought adventure and the riches of King Solomon's Mines. In the 19th century, Carl Mauch, an adventurer, a man of courage, a geologist and surveyor, visited Great Zimbabwe. He described the site and published his journals in 1874 and first drew attention in a vague way to the ruins. He reported that there were Shona people living there. It was not until 1890 and the invasion of the British South African Company (BSAC) of Rhodes and the pioneer settlement in Bulawayo that there was an interest in the earlier history of Great Zimbabwe, or as it was called in those days, the Zimbabwe Ruins.

In the early 1890s, the BSAC employed James Theodore Bent to survey Great Zimbabwe. But Bent was what in those days was called “an antiquarian” which is a polite way of describing a curious amateur. He and his wife had done excavations in the Aegean, more the style of the notorious German Heinrich Schliemann and his Greek wife Sophia who first followed his hunches in Mycaenae and then in Troy and ensured that the the Mycaenean and Trojan artifacts went to Berlin (and were later looted by Russia in the Second World War).

The check pattern seen at Motloutse, Botswana in a wall – characteristic of palaces dating from the Khami period (Penguin Random House)

Huffmann and Main do not mention these obvious comparisons but acknowledge that the early documentation by men such as Bent, Swan and Willoughby contributed little to understanding the origins of early African societies. There was always the temptation to loot or treasure hunt and it was the prospect of gold finds that had early prospectors crawling all over Southern Africa.

Ironically, Rhodes may well have had a far sharper grasp of the value of the ruins and stonework remnants at Great Zimbabwe. Rhodes financed George McCall Theal’s research and publication of the historical archival records of South-Eastern Africa. These early efforts at excavation and interpretation concluded that Great Zimbabwe was of Arab origin, betraying a colonial bias against the possibility that Africans could have built those giant stone cones.

Giant Stone Cones at Great Zimbabwe (Wikipedia)

Another early treasure hunter was Frederick Burnham, an American adventurer who joined the BSAC but ruthlelssly plundered the site of Danangombe, the Capital of the Rozvi State and located on the Zimbabwe plateau 120 kms from modern Bulawayo. W G Neal and G Johnson were prospectors looking for gold and gold artifacts at the Mundi site. Everyone thought these old ruins were the best places to look for treasure. The tragedy was the lack of professional archaeological expertise even in those early days and the lack of government regulation of these treasure hunters.

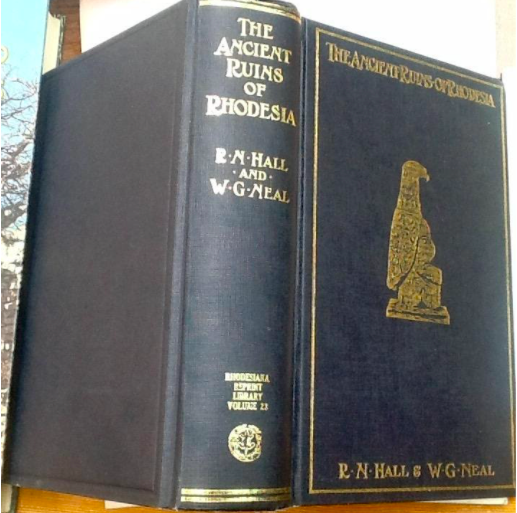

The British South Africa Company allowed Neal and Johnson to form a company to search for treasure, the Rhodesian Ancient Ruins Co Ltd. and between 1895 and 1899 they looted Zimbabwe sites such as the Khami ruins and Danangombe. In 1900 the company closed down in the face of criticism of the damage done but Neal then attempted to gain a respectable veneer with the publication of a book, The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia (written with an English immigrant journalist, R N Hall); they argued too that Great Zimbabwe was Phoenician or Sabaean.

Cover of classic work The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia by Hall and Neal who were totally wrong in their suppositions about Arab presence and construction at Great Zimbabwe (Kathy Munro)

Hall continued the tradition of swashbuckling amateurs being given spurious authority, with the BSAC appointing him as the Curator of Great Zimbabwe. In the process of supposedly clearing vegetation he destroyed priceless archaeological evidence. He was dismissed by the BSAC in 1904. Clearly there was interest in finding answers but only a stumbling towards professionalism. A breakthrough came with the 1905 meeting in South Africa of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the work of a trained archaeologist David Randall MacIver who in a close study and a report on the ruins in Zimbabwe concluded that indigeneous people had built these structures no earlier than the 14th century. Randall-MacIver was not popular with the settler population who favoured an Arab rather than an African origin despite the now mounting evidence to the contrary. The Public Works Department of the Rhodesian government, however, did further damage.

Huffman and Main are keen to ensure that the latest research is made known and to explain why archaeology is important. Human weakness needs to be chanelled towards serious study.

For those with a stronger grasp of this more recent African history, the final chapter gives a compass point to delve further back in time and engage with the timeline, presented in a neat diagram at the start of the book - a timeline of key settlements in Southern Africa between 900AD and 1840. It is this timeline that gives a lifeline to understand long earlier stretches of settlements and kingdoms across Southern Africa.

Great Zimbabwe - The Ancient Ascent from the foot of the hill to the summit (Penguin Random House)

I think I first became fascinated with Great Zimbabwe and it was on my bucket list since I was a child. I have visited the complex twice over the last forty years. Each visit has been fulfilling and thrilling. The quickest and easiest way to make sense of Great Zimbabwe is to visit the complex; take a day if not two to wander about, see the museum and get a sense of the geography and topography of the place. Ask yourself why people settled here hundreds of years ago and as you explore with the Main / Huffman book and a map in hand, the answers will come to you. I am convinced having visited Machu Picchu (Peru), Angkor Wat (Cambodia), the Pyramids and Luxor (Egypt), Pergamum, Ephesus, Troy and other Asia Minor sites (Turkey) that Southern Africa has archaeological drawcards as impressive as these other World Heritage Sites. I remain surprised that there are so few visitors. Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa are must see places. It gave me as great a thrill to see the Mapungubwe Gold Rhino and other precious items exhibited at the University of Pretoria as seeing the gold of Troy in Moscow.

This guidebook compares favourably to the many other guidebooks for other world heritage sites. Mike Main (who is described as a lay archaeologist, freelance writer and management consultant) and Tom Huffman (Professor Emeritus of Archaeology at Wits) have written a compact, dense, informative but accessible guide to the mysteries of Africa. Their book is well supported with excellent illustrations, explanatory guidelines, timelines, a bibliography for further reading and maps. There have been other bigger books of a more academic nature; but the advantage of this small volume is that it is dense but light to carry and easy to read, gives a quick summary of the latest research with flair. It’s a book that sparks curiosity. If you are an enthusiast of heritage, African history, or archaeology this is the ideal guidebook.

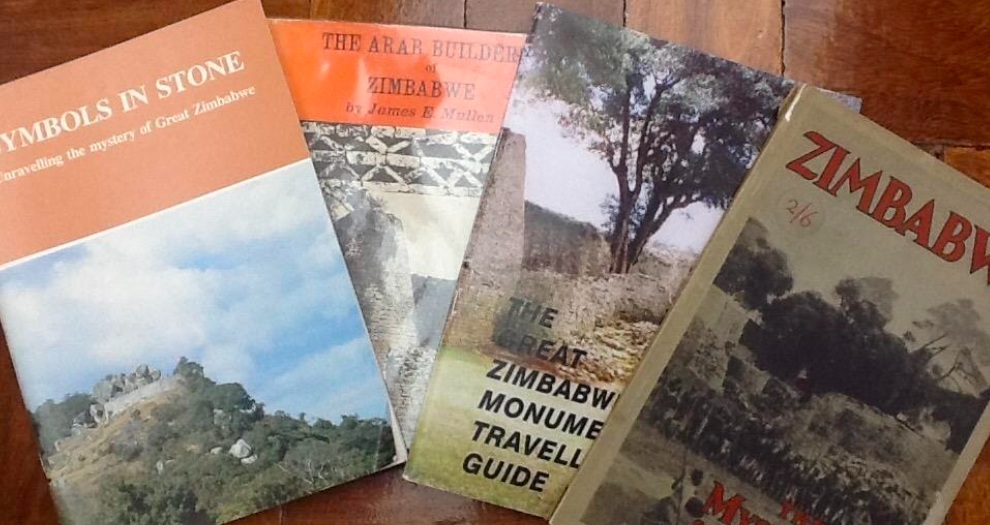

Covers of earlier booklets and guides to Great Zimbabwe including a useful book – Symbols in Stone by Tom Huffman (Kathy Munro)

Selection of old guide booklets on Great Zimbabwe. Some of the older books promote myth and false history such as that Great Zimbabwe was built by the Arabs. Old guidebooks are collectable. (Kathy Munro)

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.