Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Modern High Speed Rail (HSR) is regarded as being an independent railway dedicated solely for passengers and built to standards which allow trains to travel along its rails at speeds in excess of 300 kph (185 mph); thus enabling it to compete with short haul airlines. A case in point is the “Eurostar” service, between London (St Pancras) and Paris (Gare de Nord) that has a journey time of two and a quarter hours, via the Channel Tunnel, with the benefit to the traveller of going from city centre to city centre.

In the last six decades, many HSR services have come into being, commencing with the Japanese “Shinkansen” (a.k.a. Bullet Train) that was inaugurated in 1964, between Tokyo and Osaka, with an initial speed of 200 kph (125 mph). In the years since, the “Shinkansen” has been extended eastwards of Tokyo and westwards of Osaka with the services now travelling at speeds of 300 kph. This need for speed has been replicated in France, Germany, Spain and China, with Indonesia being the latest to join the club with its own brand of HSR called “Whoosh”, between Jakarta and Bandung, which was launched as recently as the 17th October 2023, to coincide with the “Chinese Belt and Road” Summit which took place in Beijing.

I could expand more on modern day HSR’s, and discuss the merits of the French TGV (Train a Grand Vitesse) or the German ICE (Inter City Express), but there is so much information out there that I respectfully ask the reader to “Surf the Net” for articles written by those more learned than I. Instead I would far rather tell you about what I consider to be the original High Speed Rail – the Great Western Main Line between London & Bristol of 1841.

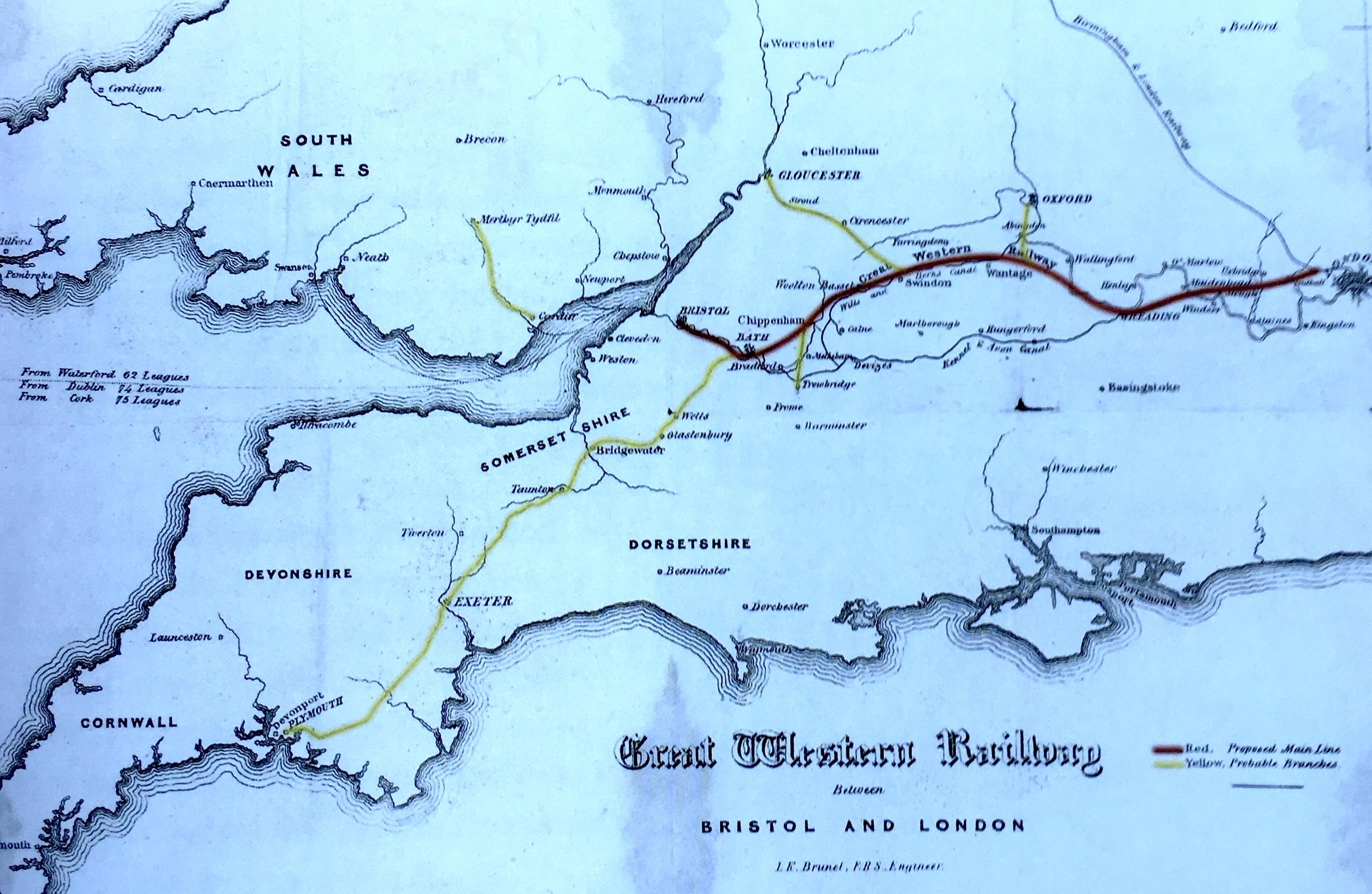

Plan of the Great Western Railway from the 1834 prospectus

Now if we could be transported back 180 years (to 1843) it would be into a world in transition and no more so than Britain, where the country was in the grip of “Railway Mania” and many Bills proposing railway links between towns and cities were being read before Parliament. Ten years prior (1833) there was but one inter-city railway, that being the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (opened in 1830), yet there were several more being proposed such as the Newcastle and Carlisle, the London and Birmingham, the Grand Junction (Birmingham to Warrington) and the Great Western Railway (London to Bristol via Bath).

Before the coming of railways long distance travel overland was on the roads (such as they were) by Stage Coach, Post Chaise or on horseback and there was always “Shanks’ Pony”, that is to walk. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was ground breaking and proved beyond doubt that the steam locomotive (Iron Horse) was up to the task of pulling wagons along a reasonably level railway line over considerable distances. Its success was not only in the efficient transportation of passengers and goods but also that it could turn a tidy profit, which in turn stimulated investors to speculate in this new mode of transport.

The Northumbrian, George Stephenson (1781-1848) was the man who engineered the L&MR and he would become known as the 'Father of Railways'. It was his credo that all railways should have the same rail gauge (i.e. the width between the inner faces of the rail heads) and he chose arbitrarily the measurement of 4ft-8½ in. (1435mm), which would later become the Standard Gauge. Stephenson would employ young engineers to assist him and when the time came for him to take a step back, the ablest of his assistants, Robert Stephenson (his only son) and Joseph Locke would take over where he left off. The former would engineer the London & Birmingham and the latter the Grand Junction. They both would keep the rail gauge as per the L&MR, as through running from London to Liverpool and Manchester was the final goal.

The city of Bristol was a major port 105 miles west of London and its commerce was based on its trade with North America. Bristol’s main rival for this lucrative trade was Liverpool, and the merchants therefore wished to pre-empt any move made by their Liverpool counterparts to improve communication with the Metropolis – London. What was there to do? Build a railway of course. A railway between Bristol and London had first been mooted in 1824, but attempts to give practical effect to the project had failed. It was not until the autumn of 1832 that the issue was raised again and by 1833 the embryonic Bristol Railway had appointed its Engineer and had given itself a new name, the “Great Western Railway”(GWR). That engineer was the young Isambard Kingdom Brunel (27 years old), who would in a matter of five years defy the Status Quo of railway building as propounded by George Stephenson.

Bristol Harbour in the mid-1800s (Wikipedia)

I.K. Brunel was an original thinker, a polymath who could work from first principles and he was not prepared to tag along with the “Stephensonian” point of view when it came to building a railway. His railway would be the “Finest Work in England” and thus he set about putting his vision into practice.

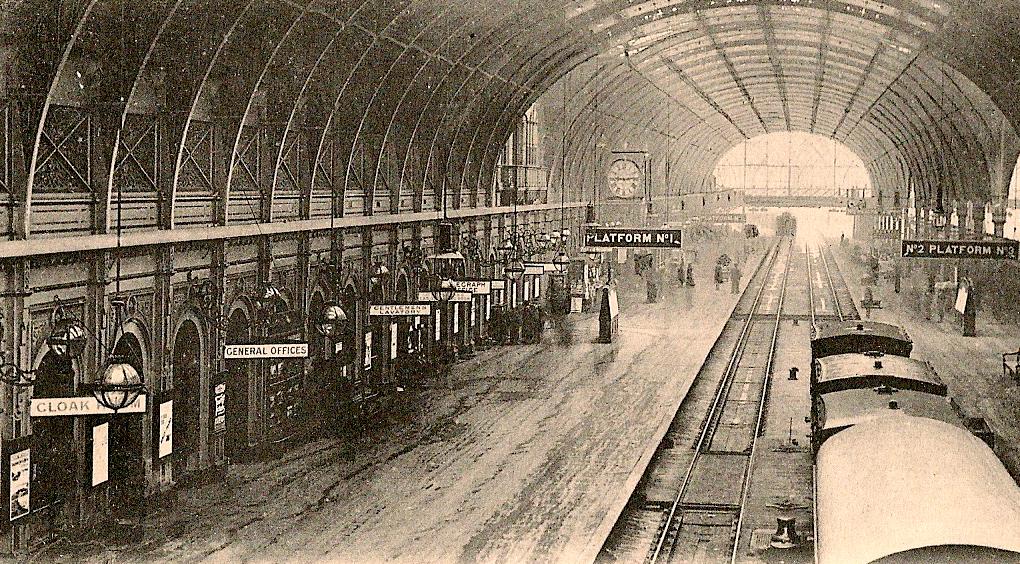

The Great Western Railway Act was given Royal Ascent on the 31st of August 1835, based on a survey done by Brunel himself and the route he so chose was one of easy grades (at least east of Swindon) that was given the sobriquet “Brunel’s Billiard Table”. At its London end it was proposed to join the London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) at a junction at Lower Place Farm, nearby to the present day location of Willesden Junction Station. The idea was that the two railway companies would then share the same terminus at Euston, with the L&BR owning the station and the GWR occupying its west side as a tenant. Even though the Engineers of both companies were in accord, Brunel for the GWR and Robert Stephenson for the L&BR, their Directors could not agree on the financial terms of the lease and the idea of a joint station was shelved. I can hear all those Paddington Bear lovers breathing a sigh of relief. Brunel had a contingency plan which was to build his Terminus on a parcel of land adjacent to the Paddington Basin of the Grand Junction Canal (later to become the Grand Union), where it joins the Regents Canal. This would make for the easy transfer of goods between the railway and the canal.

Old postcard of Paddington Station (Wikipedia)

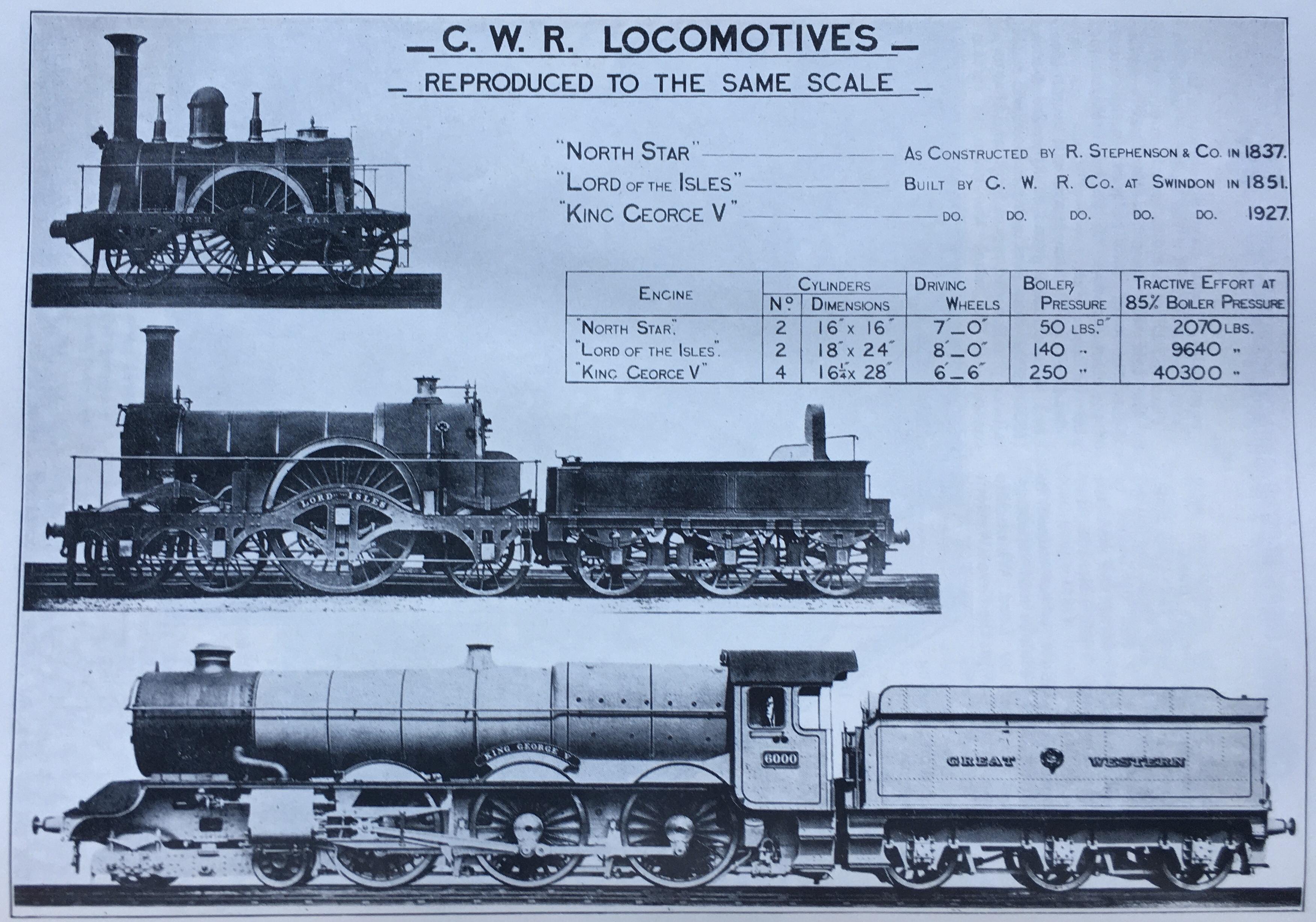

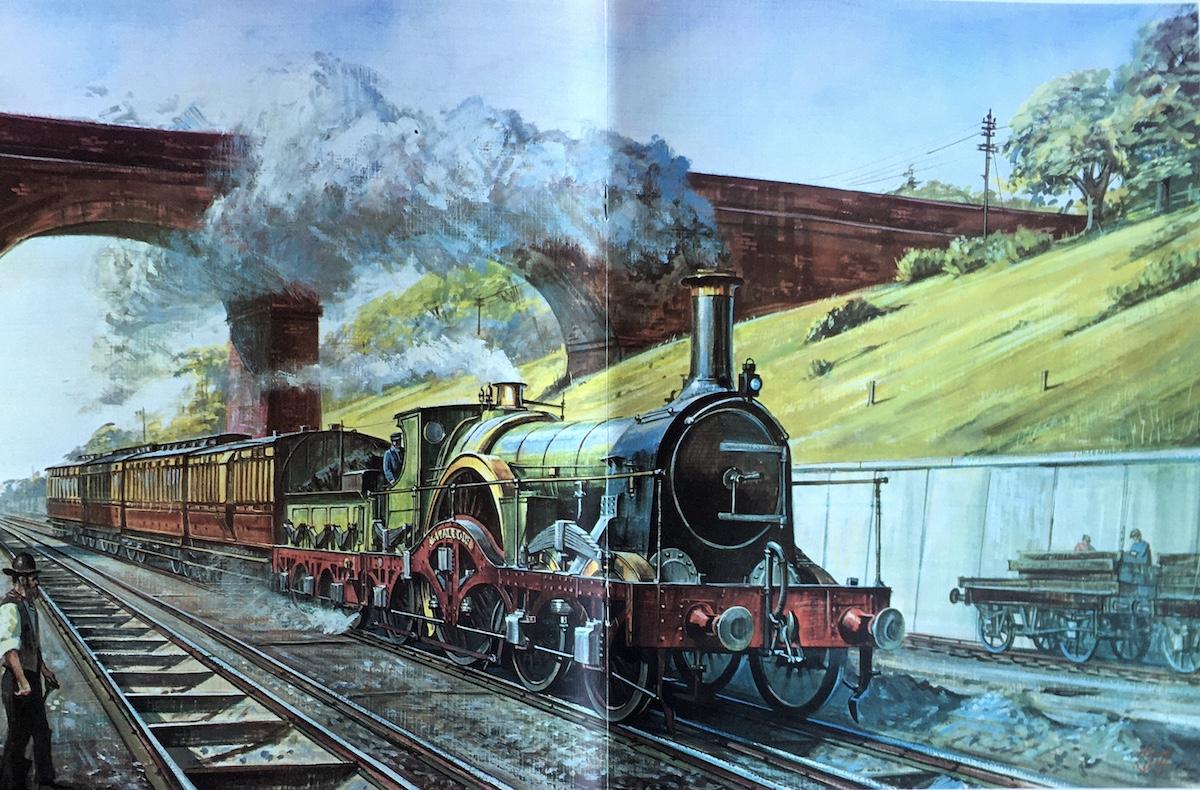

Brunel also had an ulterior motive as he wanted to pursue his “Big Idea”, his Broad Gauge of 7ft-0¼in. (2140mm), as he was convinced that the steam engines of the day were underpowered and he therefore reasoned that larger locomotives would be more powerful and faster to take advantage of his straight and level (rail)road. He tabled his “Big Idea” to his Directors and they “bought it”, such was his power of persuasion. There was however an irony as he was a failure when it came to designing locomotives and he quickly employed the services of Daniel Gooch who purchased the locomotive “North Star” from the Robert Stephenson Company of Newcastle-upon-Tyne! Gooch would take the “North Star” as his prototype in order to design his “Firefly” class of 2-2-2 tender locomotive, immortalised in Turner’s painting “Rain, Steam and Speed” of 1844, which now hangs in the National Gallery, London; the painting depicts a train at speed crossing Brunel’s two arch bridge over the River Thames at Maidenhead (see main image).

Comparison of GWR locomotives (GWR Magazine)

Maidenhead Bridge (Peter Ball)

Brunel envisaged a high speed double track railway when he laid out the GWR main line from London Paddington to Bristol Temple Meads, a route mileage of 118 miles (190 km) and when the line was finally opened throughout in 1841 the express trains would race down the line at speeds of 60 mph (a mile a minute). Gooch’s Firefly locomotives outperformed the locomotives of the L&BR as designed by Edward Bury, whose policy was to design and build small 0-4-0 tender locomotives that had a maximum speed of only 25 mph, hardly high speed but faster than what went before, the stage coach, which could only manage between 8 to 12 mph, depending on the state of the road.

Brunel certainly was a forward thinker and what he created 180 years ago was a railway that could whisk passengers along at 60 mph, six times faster than a stage coach and his line is still in use today, albeit upgraded to modern standards so that trains now speed along at 125 mph (200 kph).

Was the Great Western Railway the original High Speed Rail? Without a doubt, YES!

Gooch 4-2-2 Swallow at speed going through the Sonning Cutting (Trains Illustrated)

Post Script: Brunel’s Broad Gauge would last until the 20th May 1892, when the final Broad Gauge express left Paddington for Penzance. Thereafter the GWR would be at the forefront of railway engineering, both civil and mechanical. On the 9th May 1904 the 4-4-0 tender locomotive the “City of Truro was timed, by Charles Rous-Marten at a speed of 102.3 mph and thus is credited as being the first locomotive to exceed 100 mph (161 kph) and yet at the time it was kept secret as it was feared that such high speeds would scare passengers away!!

References and Further Reading

- “Isambard Kingdom Brunel” by LTC (Tom) Rolt, first published by Longmans Green, 1957. Republished by Pelican Books, 1970.

- “George and Robert Stephenson – the Railway Revolution” by LTC (Tom) Rolt, first published by Longmans, 1960. Republished by Pelican Books, 1978.

- “BRUNEL the Man who Built the World” by Steven Brindle, First Published by Weildenfeld & Nicholson, 2005.

- “Down the Line to Bristol” by Muriel V. Searle, first published by Baton Transport, 1986.

- “Brunel’s Big Idea and the South African Connection” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal 2018.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.