Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

South Africa is a country rich in heritage. We have incredible paleoanthropological and archaeological sites, wonderful geoheritage, and a spectrum of historical spaces and places that reveal the multi-layered stories of our past. Some of this heritage we take for granted such as the historical buildings in our towns and cities that we pass every day. Many are in a poor state but some have found new uses that have helped them to thrive into the 21st century. But what about sites and buildings in remote areas that aren't protected or have yet to find new uses?

I have been studying the blockhouses of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) since 2009 when an article in The Getaway Magazine sparked an interest which lit a passionate fire to discover more about these structures. Since then, I have documented and visited the vast majority of the survivors and written a couple of books in the process. It has been quite an adventure and one which started, right on my doorstep. The closest surviving blockhouse to my house is the one at Witkop, 30km south of Johannesburg near Walkerville on the R59 next to the Engen Garage. A trip to this blockhouse for a wreath laying on the anniversary of the signing of the Vereeniging Peace Treaty on 31 May, has prompted me to write about the sad decline of these unique heritage sites.

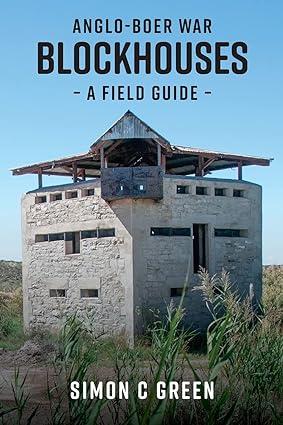

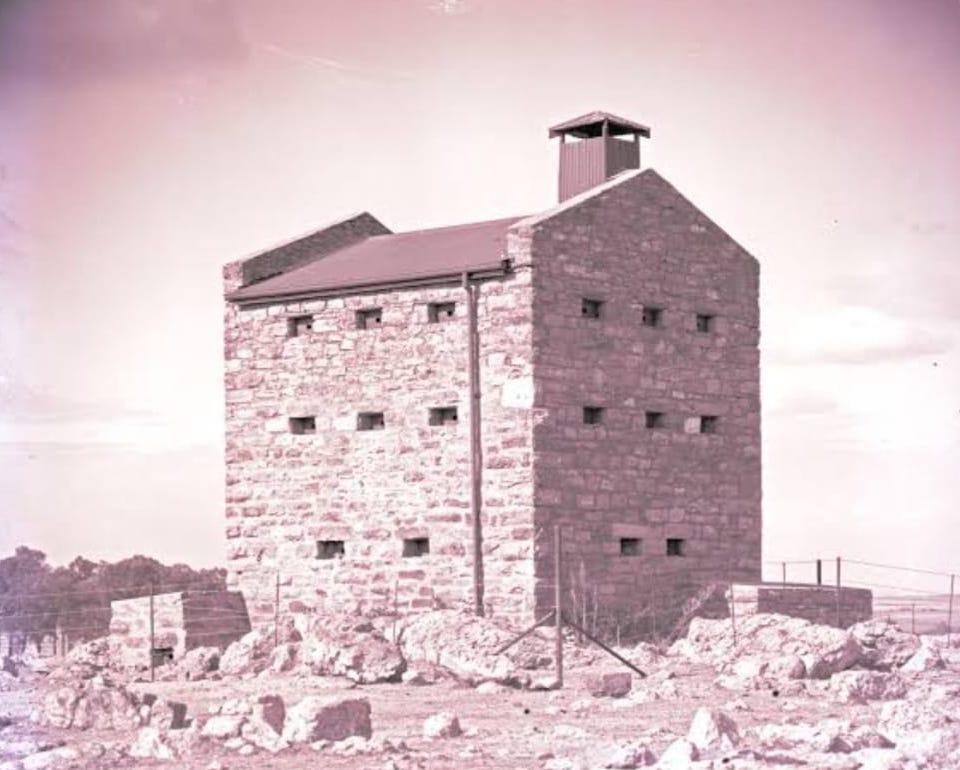

Old photo of the Witkop Blockhouse (DRISA)

A massive crack has opened up in the side of the Witkop Blockhouse (Roxy du Toit)

Why is heritage important? On taking an American military colleague to Stonehenge a few years ago, after some pre-visit excitement, his first remark on gazing on one of the most significant heritage sties in the UK was: “Gee man, it’s just a pile of rocks”. One person’s UNESCO World Heritage Site is another person's "Pile of rocks”. But piles of rocks, rock art, battlefields and buildings tell a story of our past and how we arrived at today. In telling this story, we as a species are supposed to learn from our past and not make the same mistakes all over again. We rarely do in a generational sense, but that is the purpose of heritage – to tell the story, so we can better understand our past and our present.

Ronald Balfour, British Monuments Man, said the following in 1944:

No age lives entirely alone, every civilisation is formed not merely by its own achievements but by what it has inherited from the past. If these things are destroyed, we have lost a part of our past, and we shall be the poorer for it.

The Monuments Men were specially selected men recruited into the Armed Forces to recover the treasures and artefacts looted by the Nazis in their conquest of Europe. They scoured the cellars and caves across Europe to find hidden loot and return it to its original owners. In this context, we can see all heritage as worthy of preserving. It is a ‘richness’ perpetuated in the artefacts and buildings that are scattered across South Africa. We are the inheritors of natural heritage (which is getting a great deal of press due to the effects of the destruction brought on by climate change and other factors) and of the built environment. Unfortunately we are allowing both to be destroyed at our behest or negligence.

With nearly 30-years service in the British Army, my passion for both military history and its preservation led me into reviewing how these Anglo-Boer War blockhouses were used and to tell their story in much more depth. It is an interesting story and with the Field Guide, there is a great tool for guided or self-guided tours. My specific aim was to record what I was seeing as the sites seemed to be deteriorating at an alarming rate. In this respect, it is a snapshot over the 12 years of my visits to record them and many of the photographs will be given to the South African Heritage Resource Agency (SAHRA) for posterity. How sad is that? We will be able to see images of buildings that have been destroyed in our lifetime.

Cover of the Field Guide

Although I have moved on to writing about other military topics, the preservation of the blockhouses has really come into sharp focus after my trip to Witkop. It is not, however, the only blockhouse to decline over the years. The Wellington and Beaufort West Elliot Wood Pattern blockhouses have all lost their roofs and steel galleries in the past few years, and once gone will never be replaced. To be fair, they are not Provincial Heritage sites and no one in authority is looking out for them. They are rich pickings for metal thieves, vandals and the South African climate; the three main contributing factors to decline. If you ever owned a house then you know that they need maintenance, but your house has a purpose, it is your dwelling, your propert, your financial and often emotional investment. Therein lies what I believe is the recipe for heritage survival – heritage needs a purpose – investment – commercialisation – and to provide people with jobs and income. This work is generally not achievable by heritage associations and volunteers, not to decry the amazing work many do in trying to preserve what is on their doorsteps, but it needs more serious investment and long-term integration into tourism structures.

Wellington Blockhouse (Chris Murphy)

Beaufort West Blockhouse (Simon Green)

One of the examples I cite in my talks around the country on blockhouses is the Old Gaol in Grahamstown. Once a declining building with trees growing out of the foundation, now it is a thriving coffee shop. Authentically it is well preserved and most of the original features still exist to keep the heritage professionals happy, but it also has a purpose, it is a vibrant coffee shop throughout the week for the University and during the Grahamstown Festival. Someone, probably from the University, invested in it and it now creates income and provides someone with a job, and is a local attraction, integrated into the fabric of the town’s tourism. Not every blockhouse can be a coffee shop but the aim of my Field Guide was to place them on the battlefield tourism map to get more ‘foot traffic’ to them. I think more attention in this way, more local interest, might be enough to stop or prevent future vandalism. At least it was a start. Grabbing some limelight is a good first start, and now all the surviving blockhouses are incorporated into powerful cell phone apps such as Road Trip SA. Travellers can see what particular places of interest are in their locale, or along the route of their travels or in their holiday locations.

On a recent post on facebook regarding the decline of the Witkop Blockhouse, there was much debate surrounding the worthiness of preserving such a building, irrespective that the Law mandates its protection. Comments such as “... let the British restore it!”, “what relevance is it today!”, “what’s the point – it brings no benefit, “..past reminders of death destruction and a Scorched Earth Policy is irrelevant to those who died”. Clearly not everyone is in favour of protecting an old falling down remnant of a long-forgotten world. If we had taken that logic throughout history, then much of Britain’s Roman history and historical sites would have been destroyed. The debate was quite fierce and of course typically sank into lots of vitriol which had to be removed. Those that could debate however, did bring up their own thoughts and understanding, such as the impact of colonialism and Apartheid and their legacies. Although some of the causal links were somewhat tenuous, to me it didn’t matter, as usually debate and understanding always brings us closer together. The case was won – you need to preserve the good and bad, as both have brought you to this moment, destroy some in favour of others, and it’s a biased view we take into shaping our future. The nation’s strength really does lie in its diversity and in embracing this fully, in the preservation of all heritage sites for all to understand.

This photograph shows the fragile condition of the Witkop Blockhouse (Roxy du Toit)

So, what of the priority of heritage in a nation beset with corruption, load shedding, low economic growth, post-COVID-19 legacy issues for the economy and high unemployment? The answer, to me at least, jumps out from the question... sites need a purpose and they need to generate jobs and income. To do that we have to protect them from the ravages of climate, vandalism and theft in an economic climate where I am sure there is little perceived value in heritage preservation and restoration. The agencies tasked with its protection I am sure are doing what they can – but to protect for what outcome and purpose? For me the answer lies in Provincial and local communities who can shift the focus more into the tourism sector, allowing these sites to be drawn into co-ordinated tourism routes and destinations. To do this we may have to compromise heritage integrity or the purity of authentic restoration for the sake of a commercial well converted blockhouse that acts as a café, bed and breakfast, mountain biking bothy, walkers' overnight stop or a small museum, just to cite some options off the top of my head. Where there is neglect and lack of resources, we need to see opportunity to bring tourists to our places to spend money and have fun.

So, what of ‘fun’ – what does this have to do with heritage? For me it’s a driving factor in my life, I do not do stuff that is not fun! It is also a driving factor for tourists to visit sites, they want to be stimulated or enjoy a good story. In this regard, South Africans, across the board sit with a World-Class advantage – they are friendly, love to have fun and tell a good story. Africa is a continent of story-telling where much history is passed down by word-of-mouth. We all love a good story, and are generally a sociable nation? We love food and drink too, perhaps? Here we have the recipe for great tours; travel to sites, have some ‘bite sized’ historical story recounted by a good tour guide, retire to a suitable venue for ‘sundowners’, eat some great food, reflect on the day, stay overnight and repeat the adventure in the morning…!

This is great if there are things still left to see. In the 12 years of my study many buildings have moved from Provincial Heritage Sites to ‘pile of rocks’ status. What else can we do to preserve them? In my work as an engineer from a ‘hi-tech’ background, I am always looking for applications to use in my heritage crusade; GIS overlays like Google earth, Apps such as Road trip SA, LIDAR data from archaeological studies, and the like. The most recent technology to fire me up and pique my interest is that of three dimensional (3D) scanning, in effect creating a ‘digital twin’. This is defined as:

A digital twin is a virtual model that accurately represents an existing physical space. It digitally represents a building's architecture, structure and systems. The most useful purpose of digital twin technology occurs during the construction design and planning process.

A recent study by students in France however completed a 3D scanning project in the Notre Dame Cathedral which later allowed the restorers access to an extremely accurate model – its ‘digital twin’. So thanks to Warren Thole from Leica Geosytems, we were able to create the Witkop Blockhouse digital twin. The whole process, using two Leica hand-held and tripod mounted scanners to different resolutions, scanning inside and out, took approximately one hour to complete. With the clever software a 100% accurate 3D rendered model and ground floor plan now exists for all time, even the two metre deep hole dug inside and damage to the exterior wall is accurately recorded. The data might also be used remotely by engineers to assess damage and design engineering fixes to save the blockhouse from collapse. The model can also be used for 3D ‘walk throughs’ to gain the experience of being inside a blockhouse from the other side of the world – true digital tourism.

3D scan of Witkop Blockhouse

Simon C Green is an expert on the blockhouses of the Anglo-Boer war and has published two books on the topic, and is available for talks and presentations on blockhouses and their place in South African heritage. He was born in Jersey and educated at Welbeck College. He holds a BSc (Hons) in Technology from The Open University and a Master’s degree in Information Systems from Cranfield University.

Commissioned at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in 1978 into the Royal Corps of Signals, he served for nearly 30 years in military appointments in Europe, Brunei, and South Africa. He worked extensively in major military headquarters, giving him a unique insight into the staff who fight wars at a strategic level. He was also involved in training staff officers in operational leadership and war-gaming to develop and hone their war-fighting tactics at lower levels of command. He retired from military service in 2006 and settled in South Africa to pursue his passion for military history and writing.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.