Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

There’s a war out there! Picture this…A dark smoke-filled room, the smell of burning oil, and the near-rhythmic sound of an instrument in use – the magic lantern.

The dimly lit room is filled with a curious audience eagerly awaiting the start of the show – a projection of images on a blank wall or screen.

What follows has them mesmerised. War-related images are projected one after the other from a single light source, fuelled by an oil lamp or by an electric light source. Occasional gasps and murmurs of awe can be heard from those in attendance.

The theme for the evening – The Anglo-Boer War.

The audience has a boundaryless interest in examining the sketches and drawings, alive with movement, which conjures scenes of their countrymen’s heroism and sacrifice, the Tommy Atkins of Britain.

The atmosphere is one of excitement, wonder, and anticipation. Ultimately there is even a parent in the audience who states: “My son is there”, adding to the patriotic emotions and stirring the curiosity of the remainder of the audience.

The audience hangs onto every word uttered by the ‘storyteller’ standing and narrating the images being projected one by one, and in doing so, assisting in creating mental images for the audience of the war down south.

Narratives became important during these magic lantern show evenings. Given the theme of war, the narrator, or storyteller, was in all probability triumphant, patriotic, and at times melodramatic in approach.

For the audience, it remained a unique visual experience that combined optical projection and storytelling.

The primary focus of this article is on the Anglo-Boer War sketches produced by British artists which in turn were converted to magic lantern slides and then projected at gatherings such as the one described above.

The intent of this article is not to reflect on the actual artists who produced these sketches, but purely on their artistic work that was transferred onto lantern slides for use at these themed magic lantern evenings.

The artistic slides produced during the Anglo-Boer War can be divided into three distinct categories, namely:

- The formal sketches produced by artists primarily for use by the printed media but then also converted to magic lantern slides (key emphasis of this article);

- Juvenile slides aimed at the youth. The artwork on these slides was not as sophisticated as those used by the media;

- Humourist slides. Somehow, the humour was seen during the war.

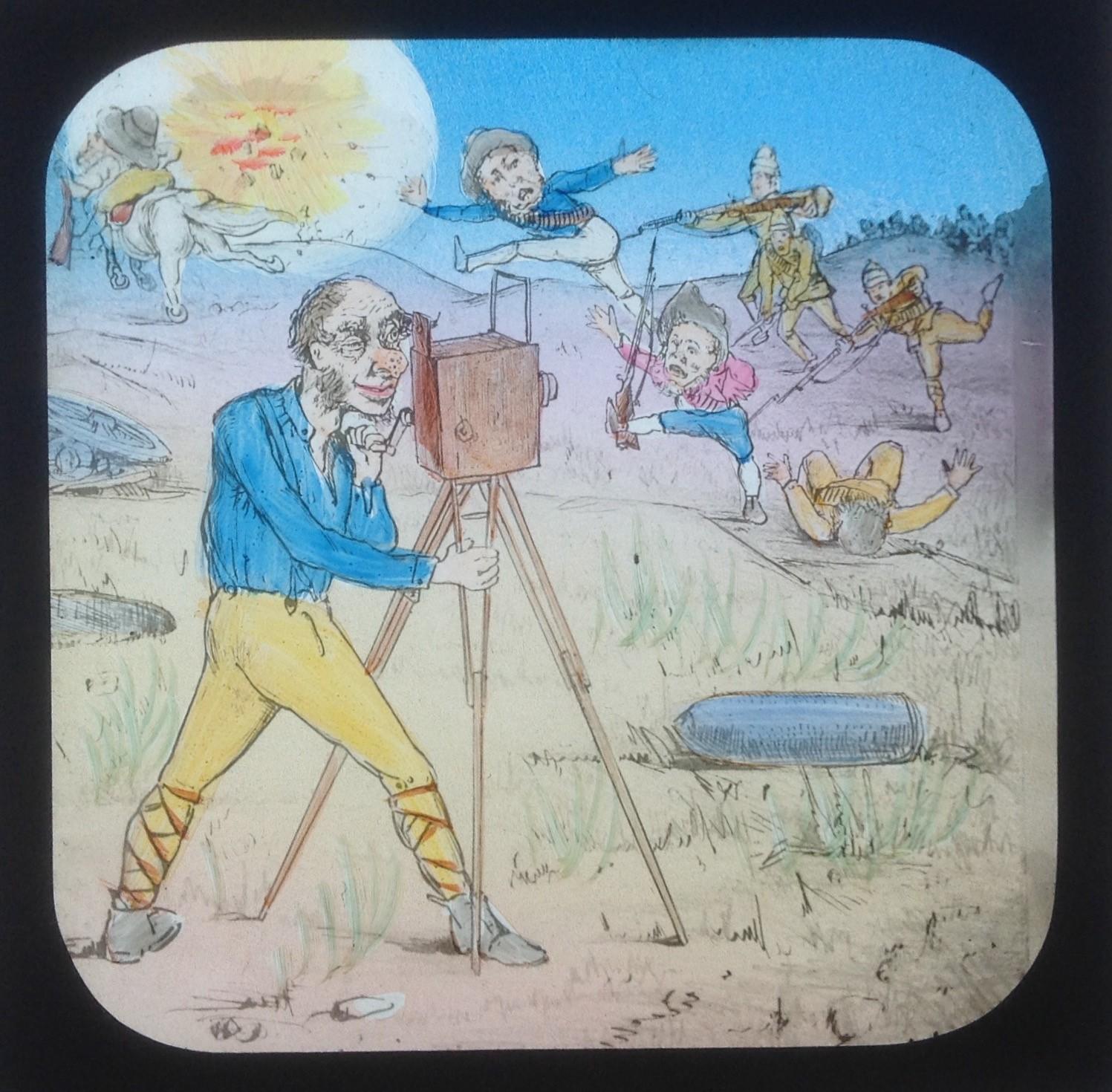

Slide number 14 from a satiric range titled: “Bill Adams ordered South”. The quality of the artwork here is not on par with most other higher-quality sketches that were utilised by the media. This slide shows a movie camera operator filming the Boers being defeated by the British

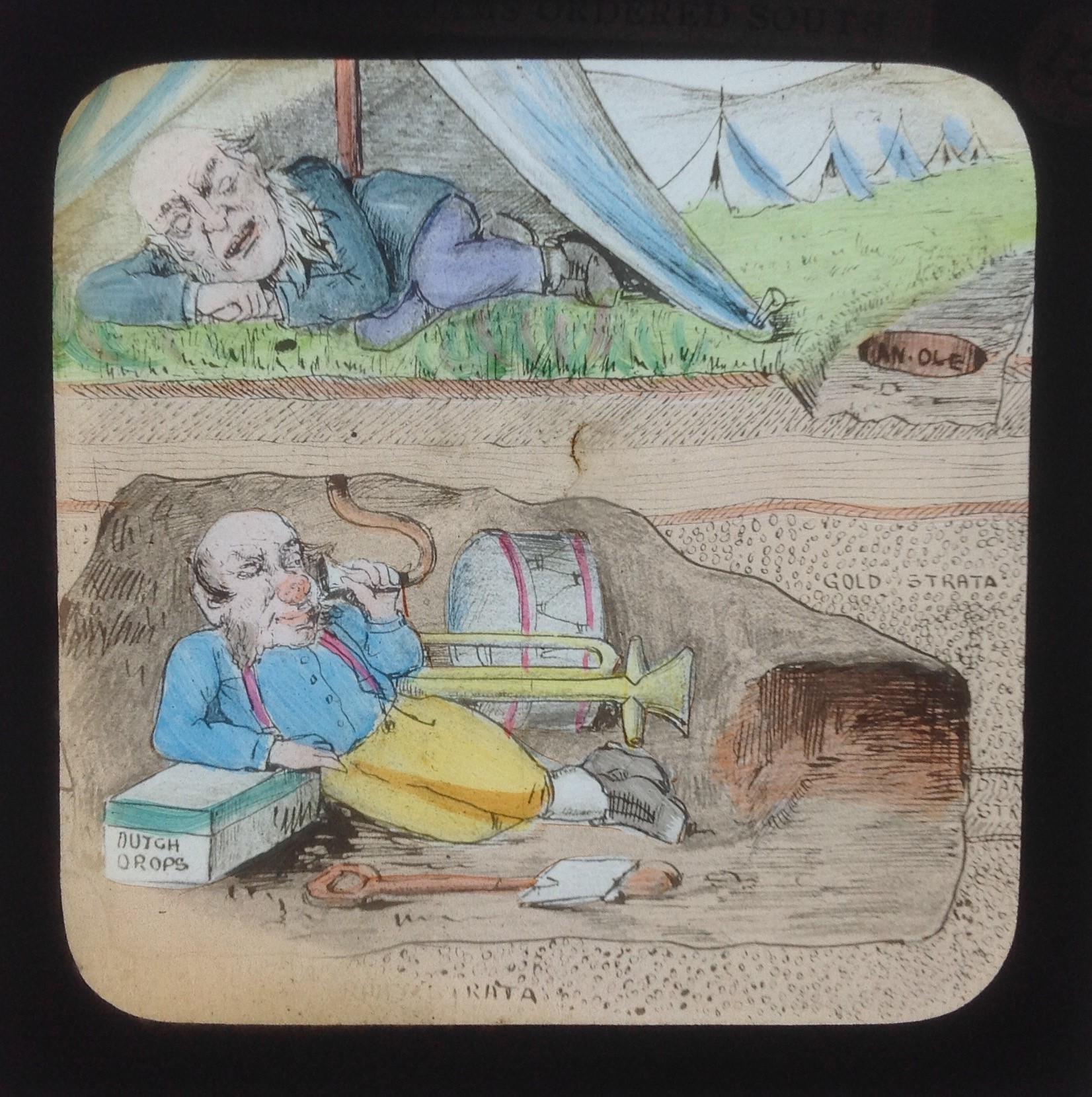

Slide number 13 from the same range. This slide shows a Dutch (Boer) soldier amongst the gold strata underground while intercepting activity above ground. Note the Dutch drops as well as musical instruments underground

This slide from the same range is titled: “The Dutchmans leetle dog (sic)”. It shows false whiskers on the left as well as Dutch drops and Gin.

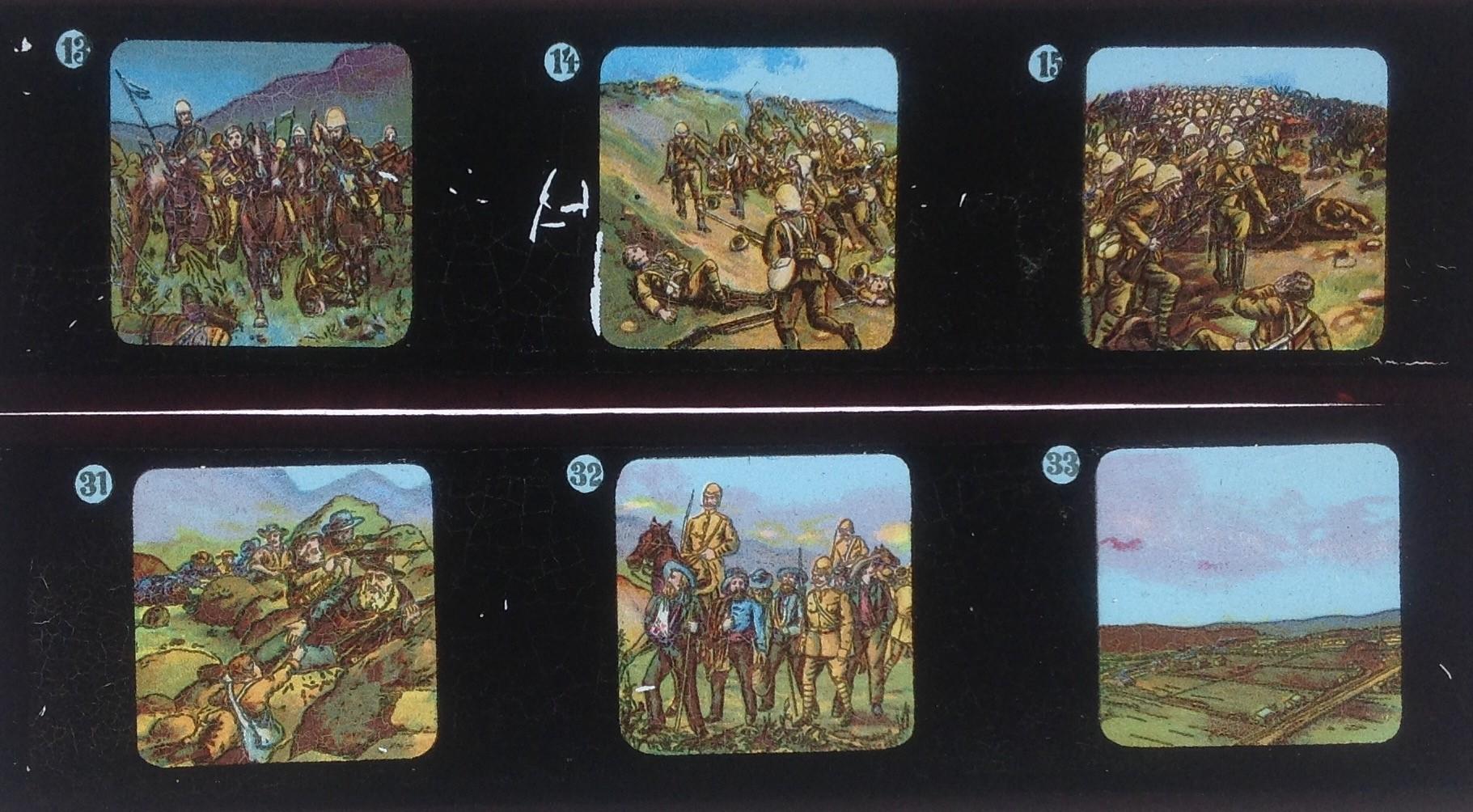

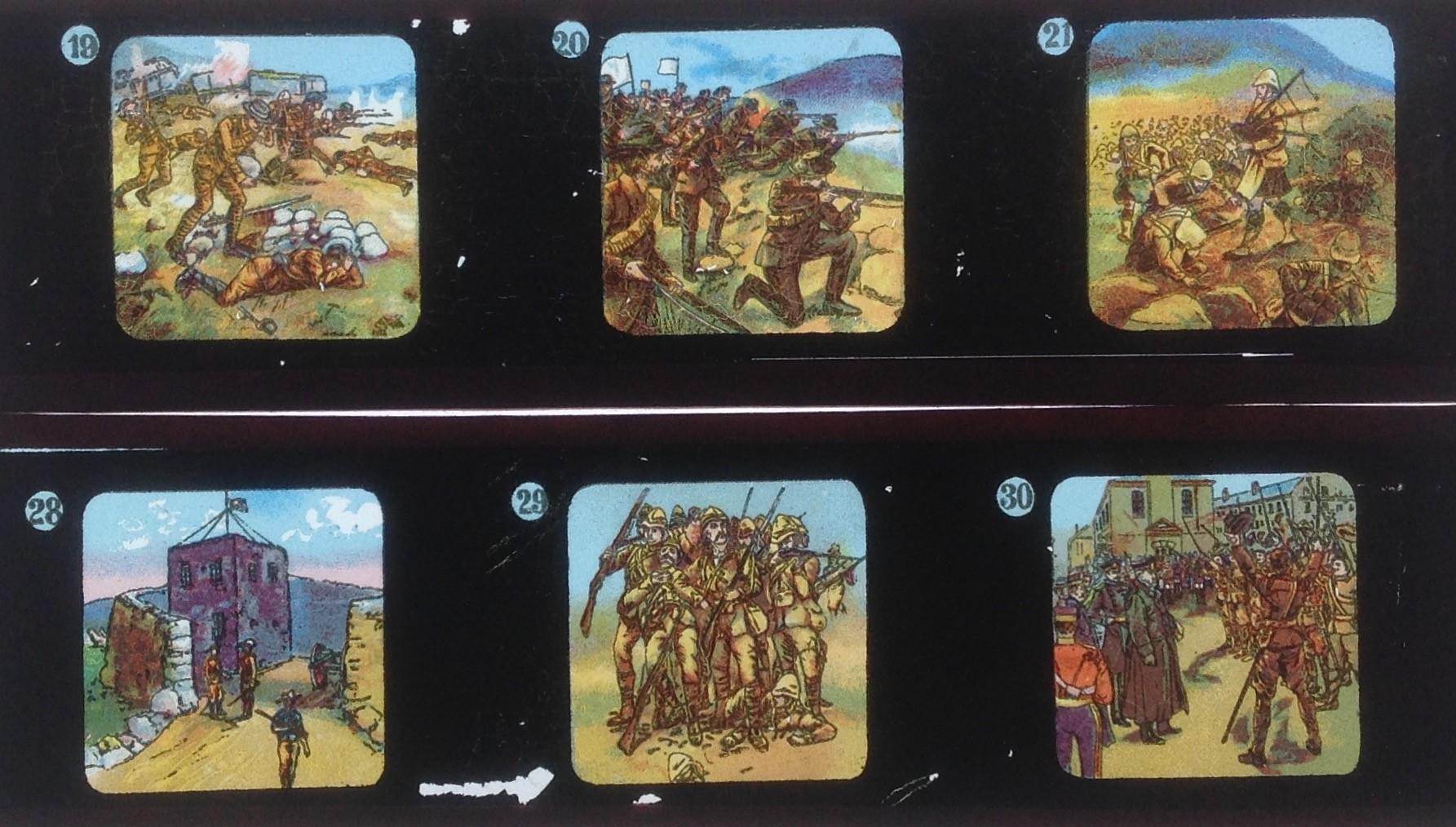

Children were also kept abreast of the war. Smaller magic lantern slides were produced for “Juvenile Lanterns” (magic lanterns made for children – also referred to as toy magic lanterns). The artwork on these slides, 15cm in length, is much more simplistic compared to those presented by artists to the printed media.

The Magic Lantern

The concept of projecting images using a magic lantern was mainly developed in the 17th century and was commonly used for entertainment purposes. It was increasingly used for education during the 19th century. Since the late 19th century, smaller versions of the magic lanterns were also mass-produced as toys.

The magic lantern, derived from the Latin name “Laterna Magica”, is an early projector that projected images (be that paintings, sketches, prints, or photographs) on transparent plates (usually made of glass) using one or more lenses and a single light source built into the lantern. These lanterns were either made of a combination of wood and steel or steel only. The lenses were mainly made of brass.

Projection via these lanterns was perfected long before the invention of photography.

Because a single lens inverts an image projected through it (as in the phenomenon which inverts the image of a camera obscura), slides were inserted upside down in the magic lantern, rendering the projected image correctly oriented.

Selected themes would have been shared at formally arranged evening events and would typically have included the lantern operator (lanternist) and the narrator. Occasionally the role of lanternist and narrator resided in a single person.

Along with the projected images, the lanternist would have read out, and even ad-libbed the script narrating the action presented by each standard sized (82mm x 82mm) glass mounted slide.

In some instances, the lanternist added music or sound effects to enhance the visual experience of the audience.

Lantern shows were typically held in theatres, lecture halls or large rooms – dimly lit to enhance the visibility of the projected images.

Visual psychology in magic lantern shows aims to create a heightened sensory experience and exploit the viewer’s visual perception and cognitive processes to produce a sense of wonder, surprise and mystery.

In use until the mid-20th century, the magic lantern, was superseded by a compact version that could hold many 35 mm photographic slides: the slide projector. Even this contemporary method of projection has fallen out of favour.

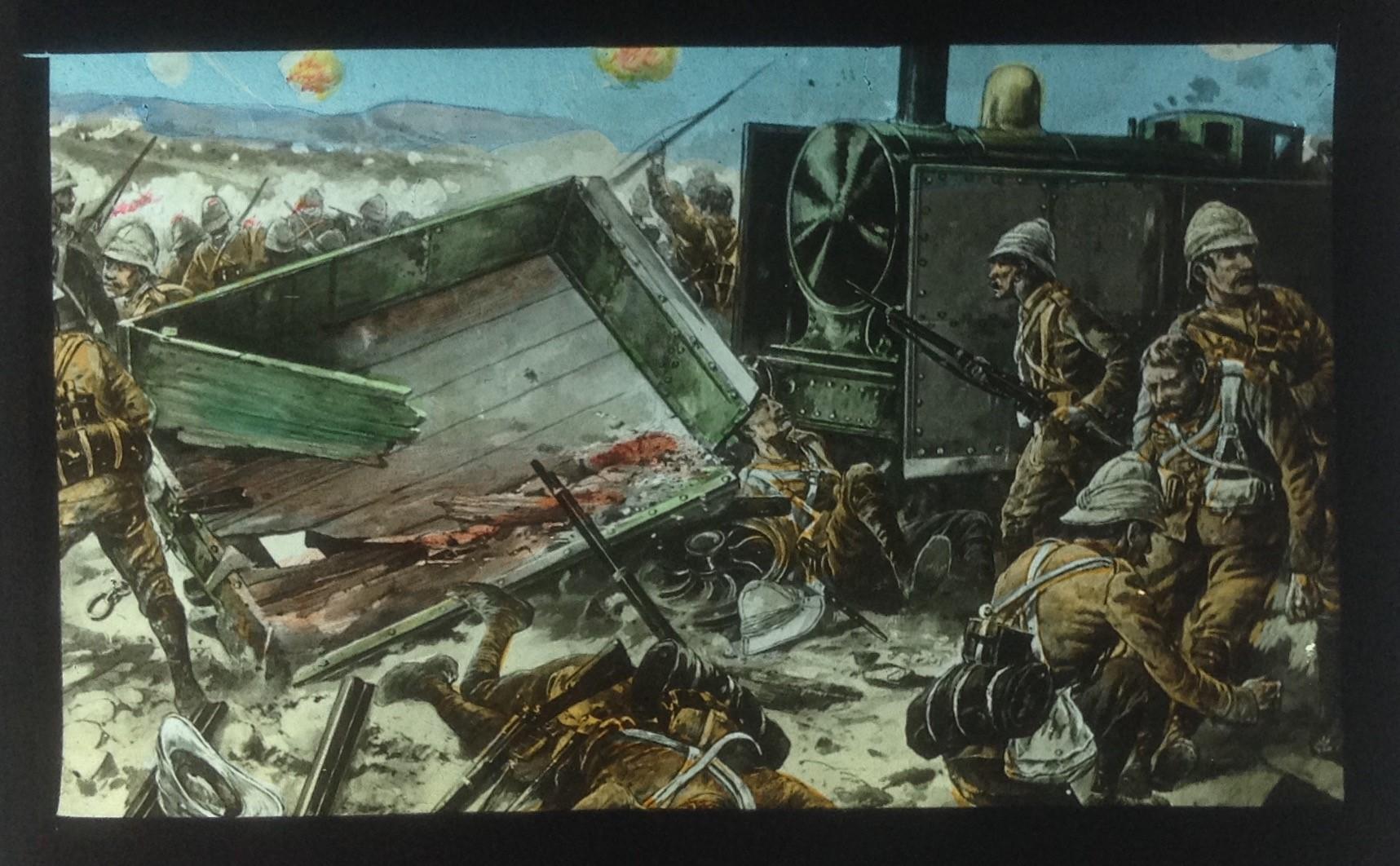

This slide, numbered 88, has a “The Transvaal War” copyright. The printed title of this dramatic scene reads: “Armoured train attack at Belmont”. The artist would not have sketched this image in colour at first. This was only done after the initial black-and-white sketch was completed. It may also have been coloured by someone else other than the original artist. Note the canon plumes in the background.

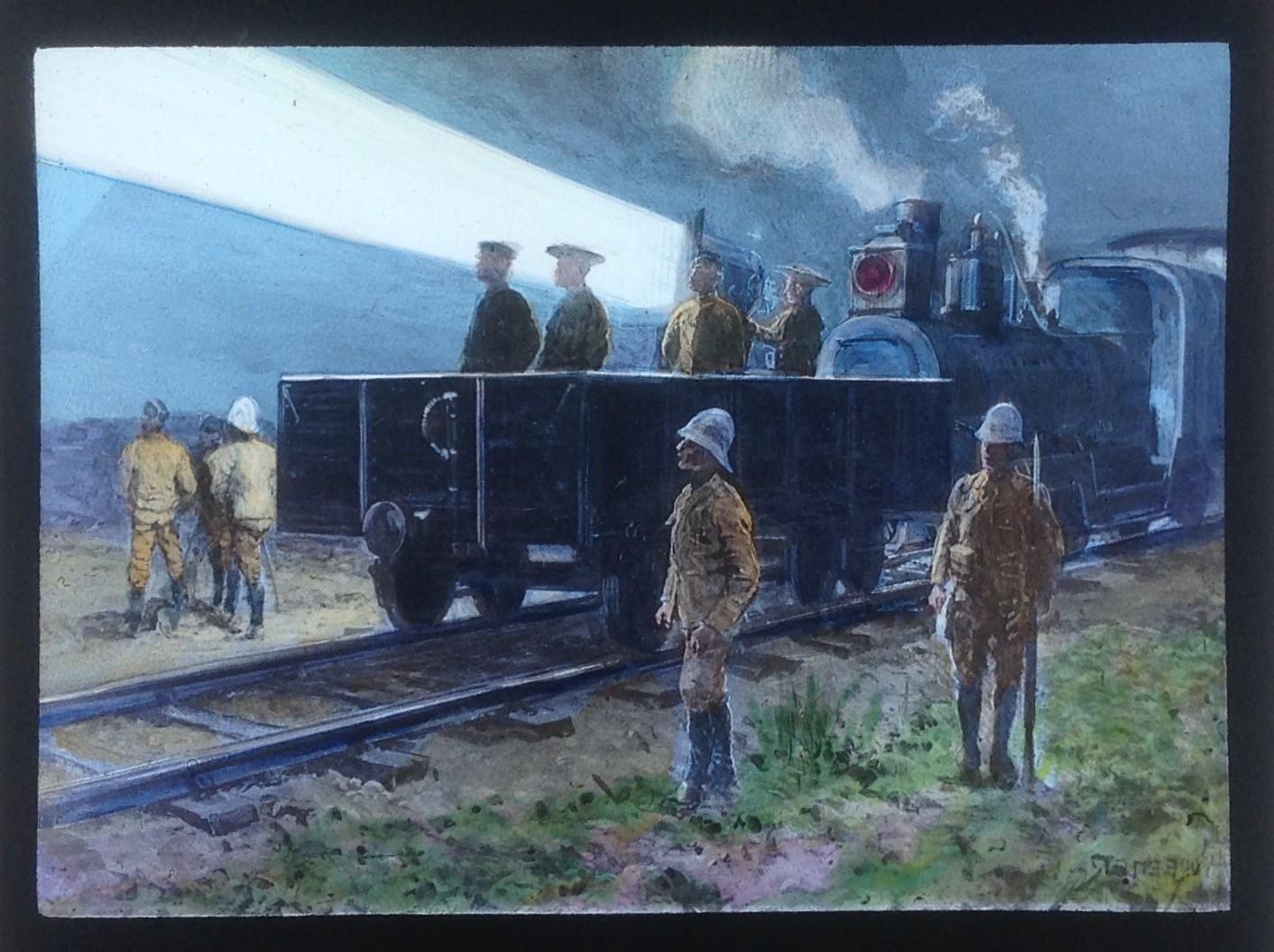

Hand-coloured slide number 159 titled: “Night signalling with searchlight from an armoured train outside Ladysmith”. Slide labelled: Copied by permission from “The Illustrated London News”. The artist, as indicated in the left bottom corner, seems to have been Keenar.

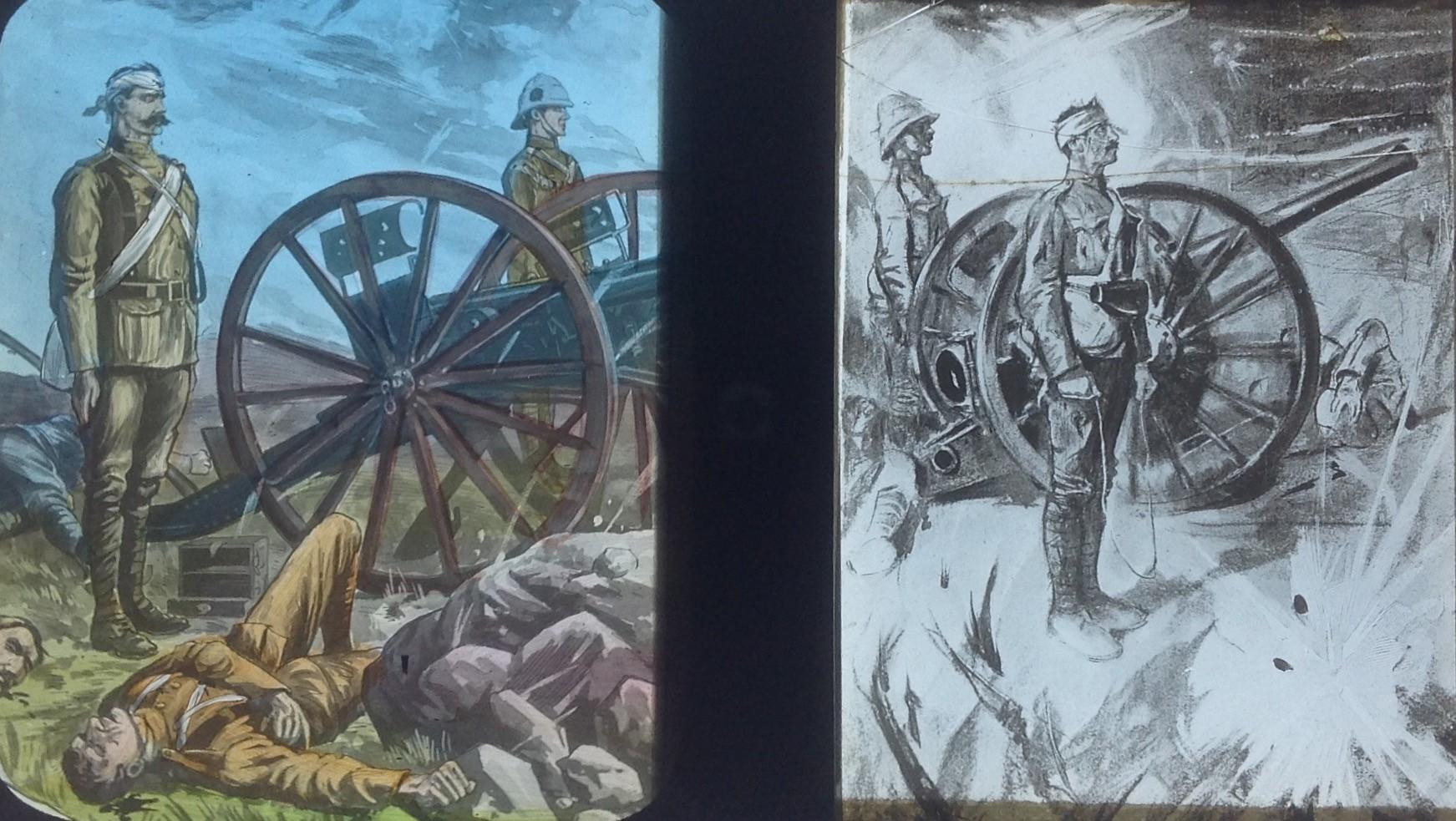

Some images were popular scenes presented in a variety of ways. These two slides in all probability convey the same scene. The slide on the left, numbered 141, carries a “The Transvaal War” copyright. The printed title on this emotive slide reads: “Heroes to the death at the battle of Colenso”. The artist would not have sketched this image in colour at first. This was only done after the initial black-and-white sketch was completed. It may also have been coloured by someone else other than the original artist. The slide on the right looks like the same brave British soldiers manning their canon with explosions taking place around them. The outer protective glass of this image is cracked. What makes this artwork significant is that the focus is on the centre of the artwork. This very same image also appears on page 93 of “The Flag to Pretoria” (Vol 1).

Anglo-Boer War sketches

During times of conflict, there was substantial public interest in any images relating to such conflict. The Anglo-Boer War was one such topic that was a popular entertainment theme. This is confirmed by the number of war sketches produced.

It has already been recorded that no evidence exists of photographs that were captured of the two parties in actual conflict.

Photographs that do show some action were all posed for.

The American photographers, Underwood and Underwood especially applied this technique in that many of their stereo photographs show posing men making it seem as if they were defending themselves or attacking retreating Boers.

What was the alternative to this lack of visual evidence of soldiers in action?

Fantastical artistry.

Boers returning from town examining their rifles. This slide was originally copied with permission from “The Illustrated London News” by London-based Newton & Co. The artist seems to have been Prior (bottom left-hand corner). Note the seated girl and her drum.

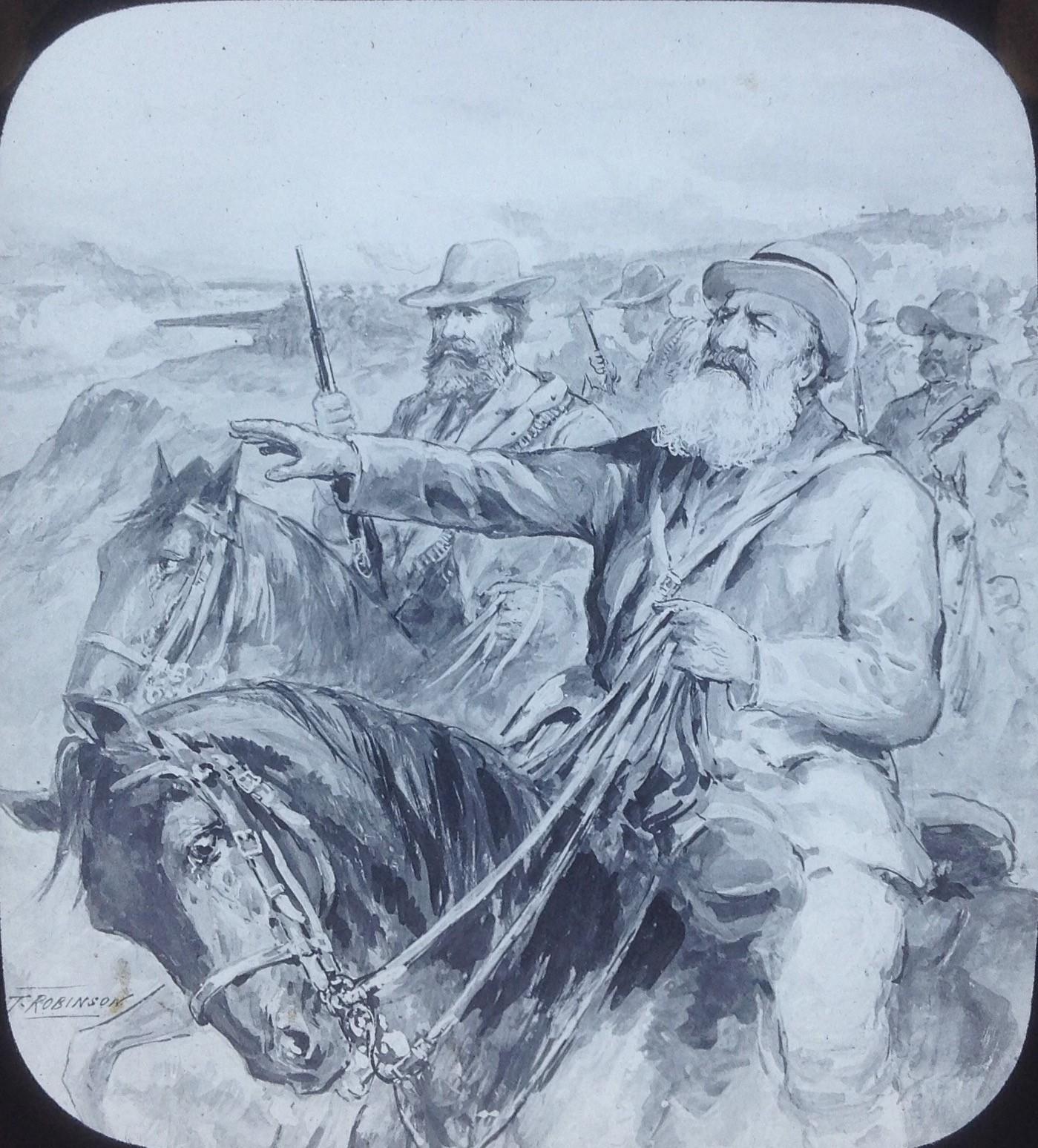

Artwork by T. Robinson showing General Piet Joubert. Slide labelled: Copied by permission from “The Illustrated London News”

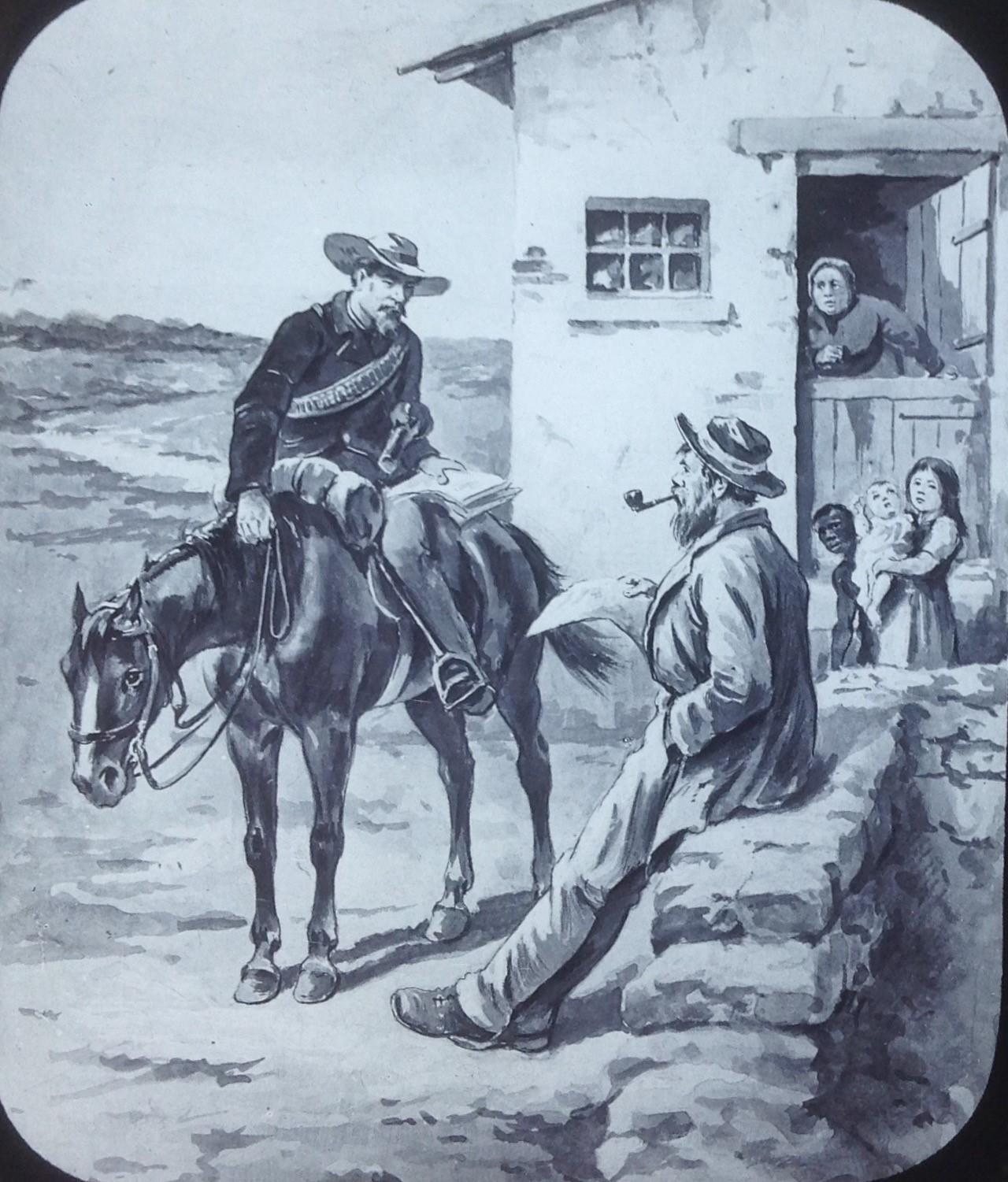

Slide titled: “Field Cornet delivering orders at a home”. Slide labelled: Copied by permission from “The Illustrated London News”

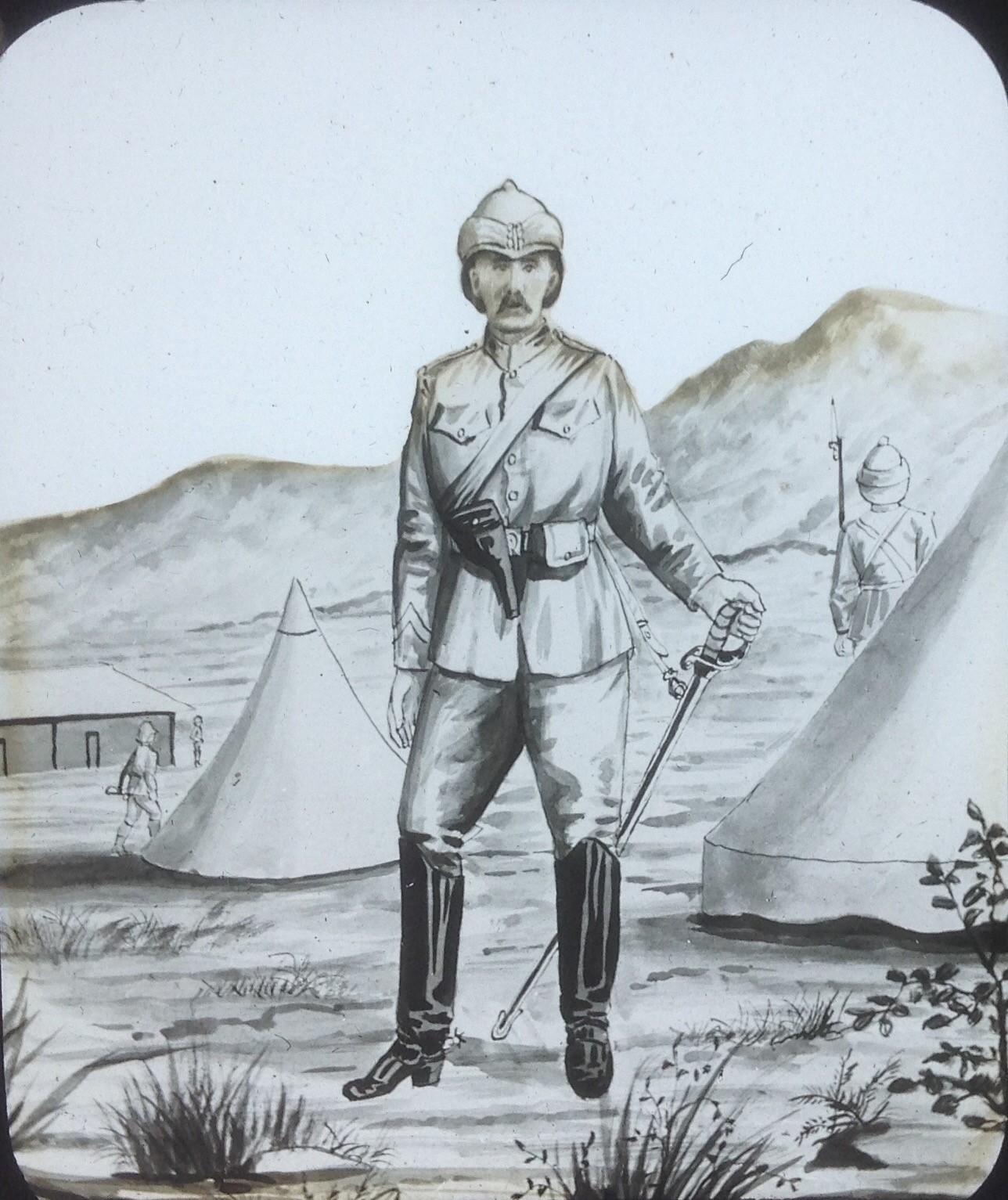

A more simplistic sketch of General Gatacre. He suffered a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Stormberg. The slide is numbered 98 with the label: “Transvaal War copyright”. This sketch may be an example of a rough sketch that was sent to the UK for further refinement by another artist. It seems the image was accepted as is in that no further refinement of the sketch was applied.

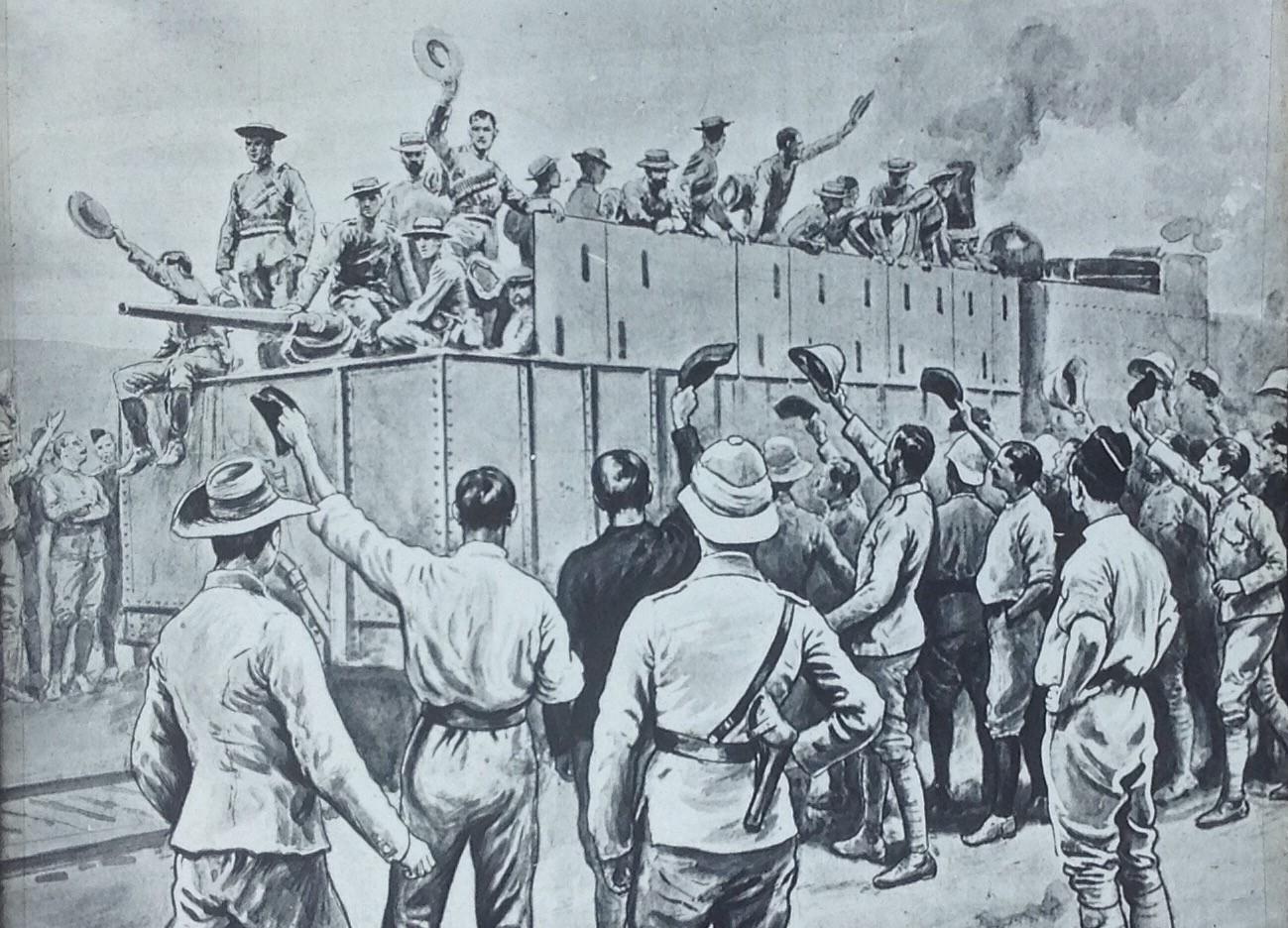

This slide contains no information. The theme seems to be that of British soldiers and citizens waving off an armour-plated train carrying citizens and soldiers.

The artists

At the time of the Anglo-Boer War (1899 -1902), photographic journalism was in its infancy. Any visual material, be it actual photographs or sketches by artists was lapped up by the visually curious.

The relation between the lantern shows and paper-based illustrated news was closely aligned in that the majority of slide images were sourced from British-illustrated news publications.

The war artist who worked for the illustrated press was at the height of their importance during the Anglo-Boer War. Four main illustrated press tabloids at the time relied on war artists to send back images of heroism. These were: Illustrated London News, Graphic, Sphere and Black & White.

The French painter, Ernest Meissonnier (1815 – 1891) stated: “The man who has seen the war is the man to paint war”, suggesting that the conflict needed to be experienced first-hand to provide a true reflection.

The ideal in creating these mental images was in creating a balance between the avoidance and emphasis of the sensational side of the battle. With some imagination added, the pictures became the evidence of an actual eyewitness account.

Talent in drawing animals, more so horses, was of paramount importance to the artist’s success.

During the Anglo-Boer War specialist artists were sent from England to South Africa to capture the war in sketch. It is these sketches, initially meant for the press, which were later transferred to magic lantern slides to be presented to audiences at magic lantern shows reiterating the grim and deadly circumstances of war.

Sketches sent back home do indicate an absolute disregard for the artist’s safety in that some scenes, be they inflated or not, indicates fearlessness just to get a sketch produced.

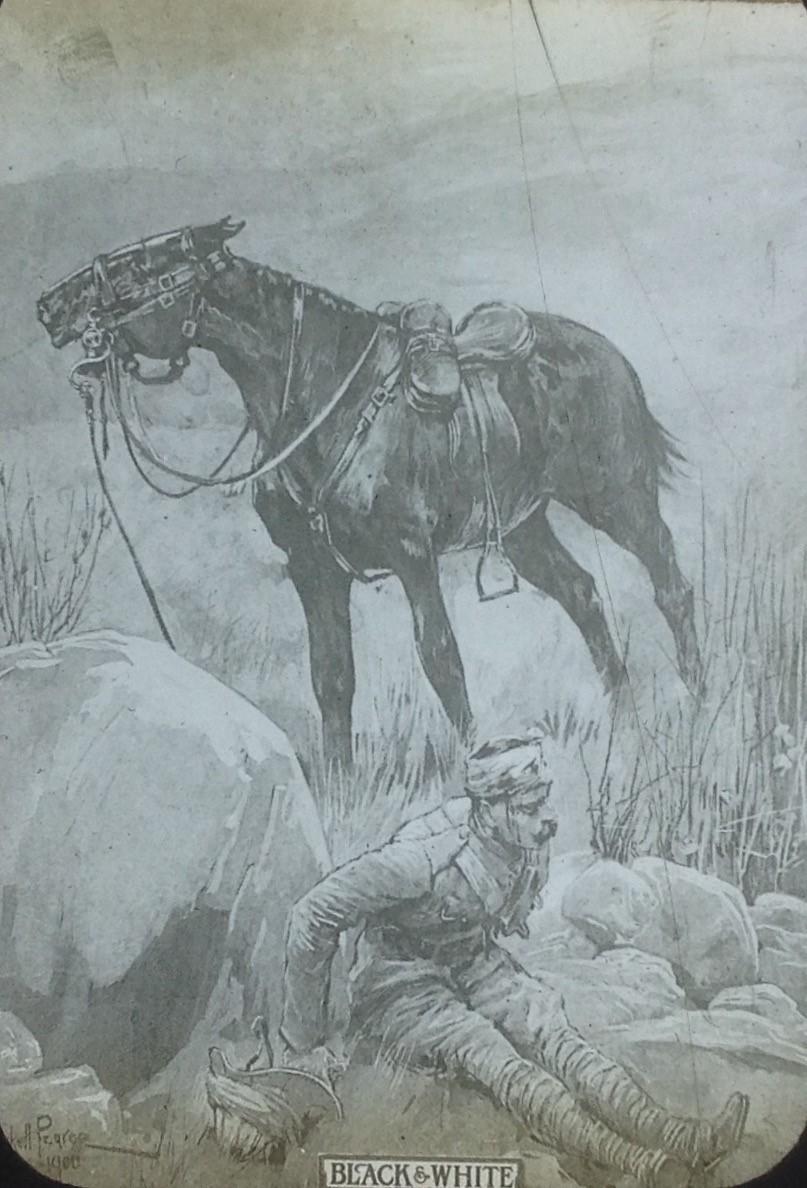

Slide numbered 213, with outer protective glass cracks, titled: “Common scene on battlefield. Horse remains by side of wounded rider”. This slide was used with the permission of the proprietor Black and White.

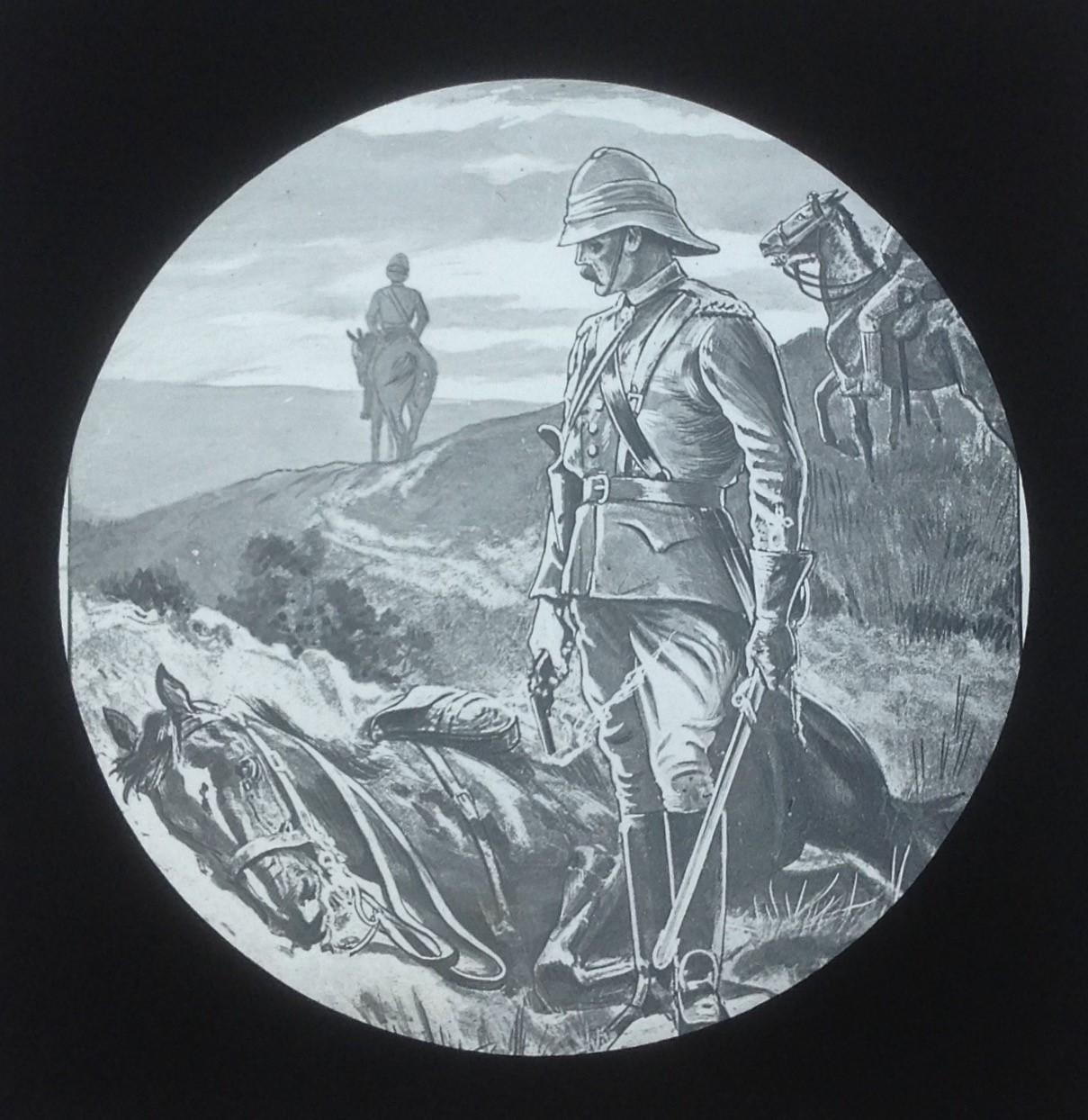

A sad scene of a British officer having to put down his horse injured in a fierce battle with the Boer. This slide contains no additional information.

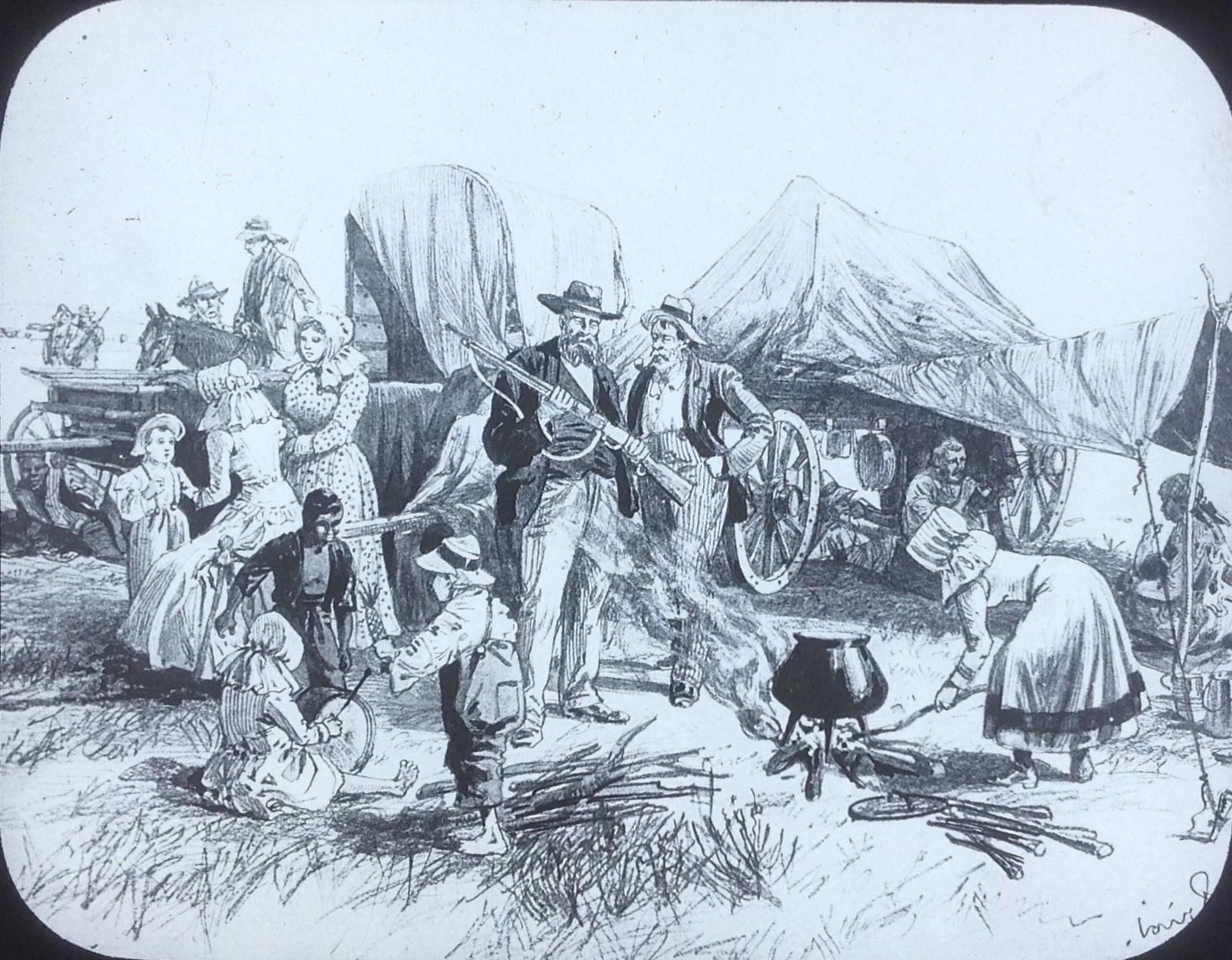

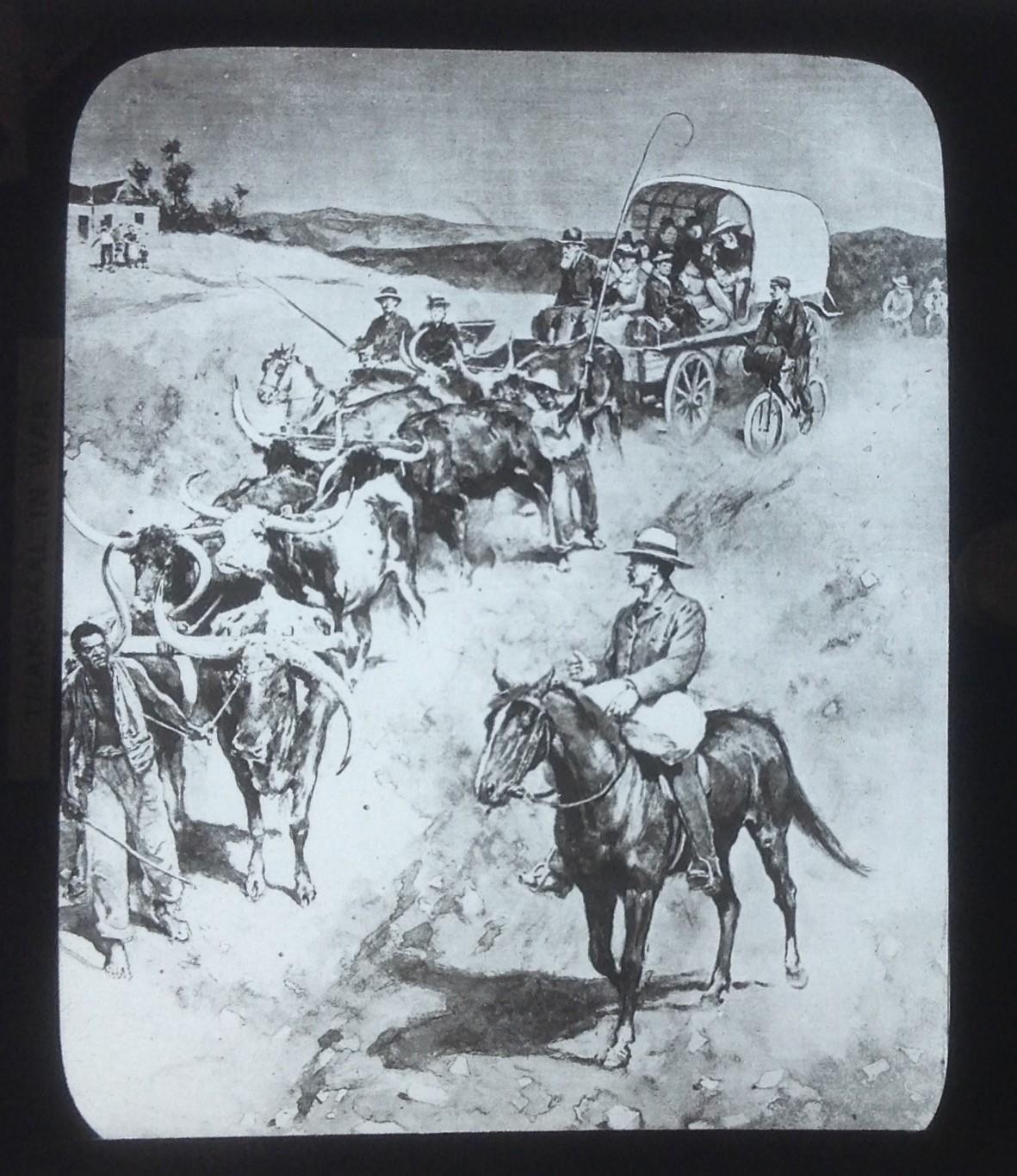

Transvaal in War – A Boer family on the move. Note the bicycle next to the wagon

A more elementary sketch showing British soldiers being nursed in a field hospital. The slide is numbered 76 and carries a “The Transvaal War” copyright.

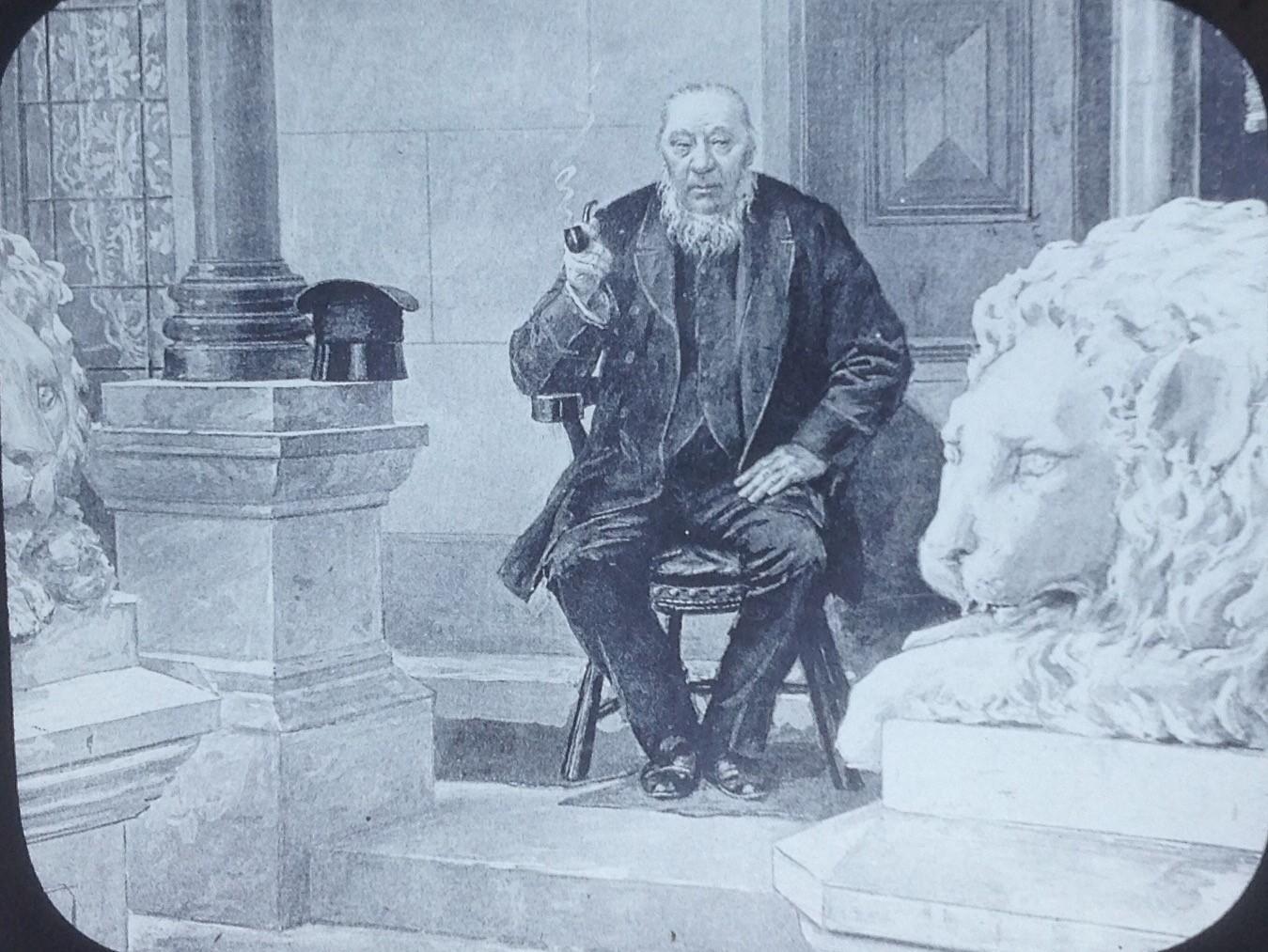

Paul Kruger on the stoep (veranda) at his Pretoria-based home. The slide is numbered 41.

Greenwall, in Carter (1999) refers to several artists that were on South African soil during the Anglo-Boer War period. Amongst them were also soldiers, one of those being General Robert Baden Powell. A military officer’s wife who also stood out as one of the greatest military artists of the time was Lady Elizabeth Butler, wife to Sir William Butler who was the commander of the British forces in South Africa just before the outbreak of the hostilities. She would, however, never have experienced any battles first-hand.

Greenwall, in Carter (1999) continues by stating that the propaganda value of the artist’s work was not to be underestimated in that the British artists were under instruction from their editors to glorify the British soldier in battle scenes, especially where the result was not in their favour. The Boers in turn were depicted as villains, either looting British dead or firing at stretcher bearers.

While one source suggests that these sketches provided a true reflection of the conflict down south, the above point by Greenwall contradicts such a stance.

As a rule, a bald sketch, crowded with suggestive mnemonics and a detailed statement is rarely completed by the original artists in the field in that the work of the original artists would have had the initial rough sketch amplified by the final artists back north. The original rough sketch was despatched in a jealous hurry to the sketcher’s employer (newspaper) where it was then allotted to a band of artists to reproduce the subject as was seen by the original artist, amplifying the additional details as carefully drawn and described. To facilitate an impactful final image, the artist in the field took abundant notes, describing the scene sketched in detail.

The human side of “Tommy Atkins” was also not neglected by the artists in that sketches were also made of soldiers at rest, at play, and in prayer.

Some of the sketches produced varied between shocking and touching while others had a humourist slant.

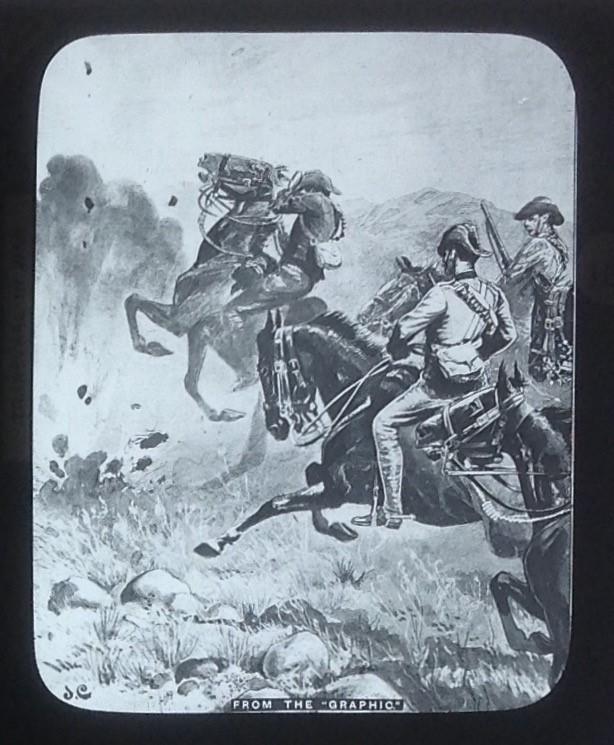

Soldiers and their horses under bombardment. This scene was sketched by an artist with the initials JC (bottom left). The image originated from “The Graphic”. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

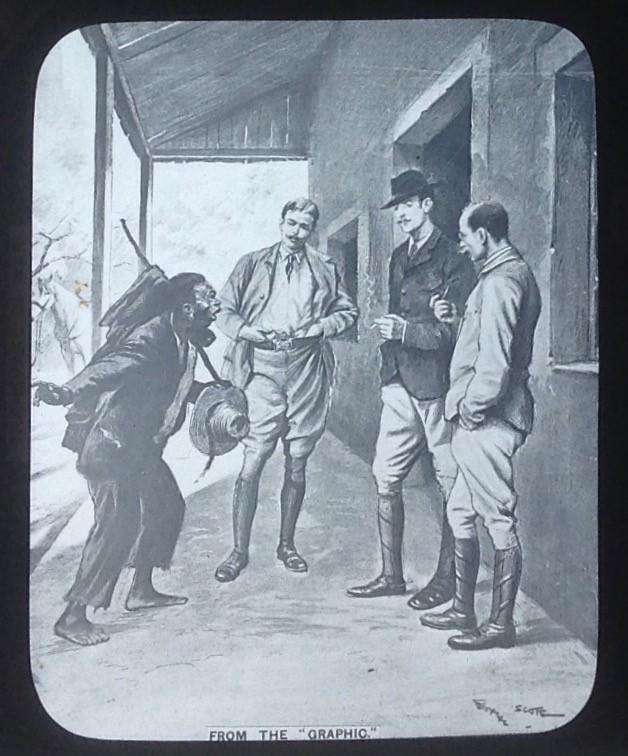

News just in. A runner presents vital information to his British masters. The artist’s name is visible in the right-hand corner of the sketch. The image originated from “The Graphic”. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

Canons in use. The image originated from “The Sphere”. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

A British soldier assisted into an ambulance wagon. The initials of the unknown artist appear in the bottom right-hand corner of the slide. The image originated from “The Graphic”. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

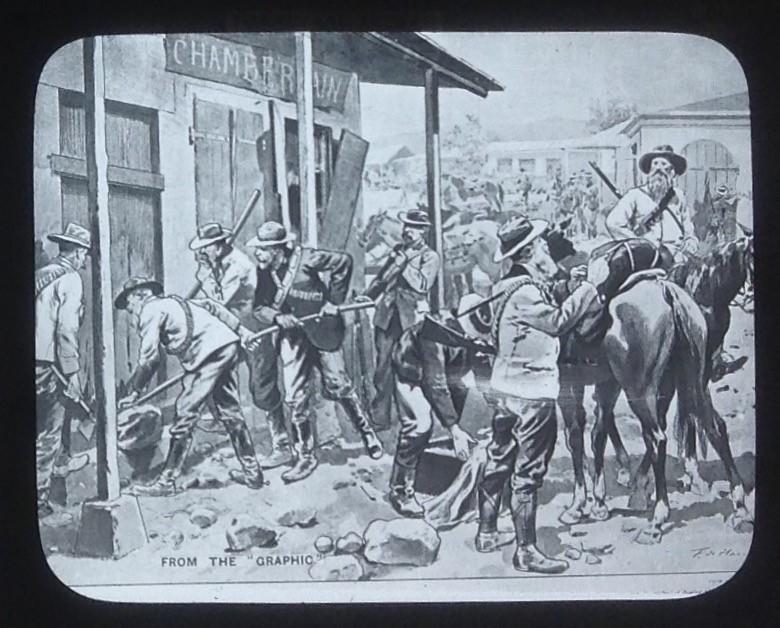

Boers cleaning up after a bombardment. This image suggests that British artists, who would have been unarmed, were also present in Boer territory to create their artwork. The artist’s details are visible in the bottom right of the image. The image originated from “The Graphic”. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

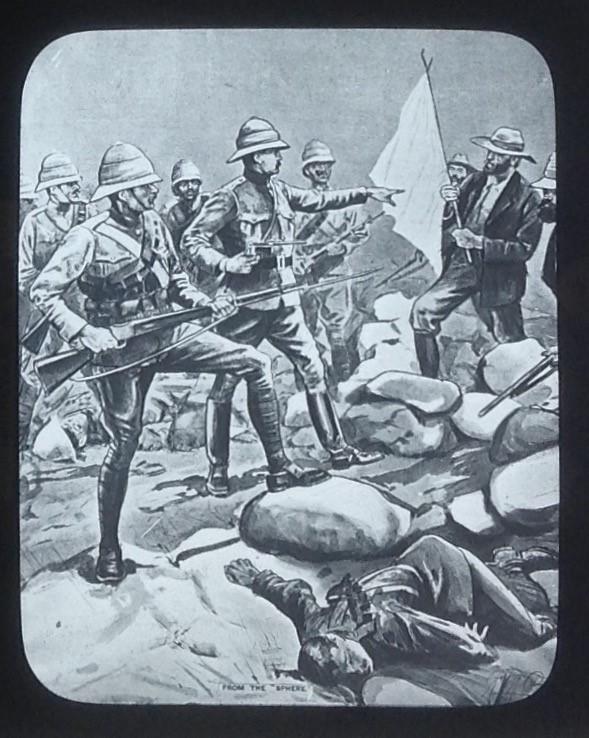

Boer surrender. The image originated from “The Sphere”. The initials of the artist seem to appear in the bottom right-hand corner. This slide formed part of the ‘Transvaal in War’ magic lantern series.

Closing

Attending lantern shows provided a unique experience and memories that combined technology, storytelling, and visual artistry.

For years, the contribution of Victorian artists and illustrators has been regarded as insignificant. Their artwork, reproduced into magic lantern slides qualifies as illuminated art and today is of significant interest to war historians and artists alike.

Advances in photographic technology/technique, including the reduction in the size of cameras and faster film, eventually saw the demise of wartime artists.

The above suggests that these shows only took place in Europe. There is a remote possibility that these shows also took place in South Africa (more likely in the Cape Province).

A key question is: Were there also South African artists replicating what the British did to inform their citizens of the war? Unlikely.

Modern-day lantern shows

In the Americas and Europe, clubs exist today where hobbyists present magic lantern shows to the public.

In South Africa, other than Mervyn Emms, who has since passed away, I am aware of only one passionate lanternist and narrator, namely Pretoria-based Paul Mellor. Mellor has a particular interest in the genesis of children’s stories and offers interested parties the experience of lantern evenings, during which he fully narrates these stories as contained on sets of lanterns slides, most of which go back more than 100 years. My wife and I recently had the privilege of attending one of Paul’s winter evening “shows” during which the story of Aladdin was passionately presented.

Any interested party can contact Pretoria-based Mellor to arrange such an evening show on paul@mellor.zone

Also, see a more detailed article on the South African history of the magic lantern slide (click here to view).

Main image: Hand-coloured slide number 159 titled: “Night signalling with searchlight from an armoured train outside Ladysmith”. Slide labelled: Copied by permission from “The Illustrated London News”. The artist, as indicated in the left bottom corner, seems to have been Keenar.

About the author: Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

Sources

- Carter, A.C.R. (1999). The work of the war artists in South Africa (with annotations by Steve Lunderstedt. William Humphreys Art Gallery. Kimberley

- Hardijzer, C.H. (2020). Latent South African visual history. (www.theheritageportal.co.za)

- King, S. (2006). The magic lantern effect. LA Times (www.latimes.com/archives)

- Wikipedia.org (extracted 30 May 2023). Magic Lantern.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.